The Sundance Film Festival is back for the first time since 2020 at its Park City venue celebrating independent film with a line-up of 101 feature-length films, from 23 different countries. This year’s festival is an in-person and online event allowing audiences all over the world to enjoy access to the latest films from 19-29 January, the online programme starting on 24th, and including all titles

The festival is divided into four main sections: US DRAMATIC, US DOCUMENTARY, WORLD CINEMA DRAMATIC and WORLD CINEMA DOCUMENTARY. There is also the MIDNIGHT, PREMIER and NEW FRONTIER strands representing /horror edgy, first and ground-breaking new titles. See the full line-up for the 2023 Sundance Film Festival below.

U.S. DRAMATIC COMPETITION

THE ACCIDENTAL GETAWAY DRIVER : U.S.A. Dir/Wri: Sing J. Lee, Screenwriter: Christopher Chen – During a routine pickup, an elderly Vietnamese cab driver is taken hostage at gunpoint by three recently escaped Orange County convicts. Based on a true story. Cast: Hiệp Trần Nghĩa, Dustin Nguyen, Dali Benssalah, Phi Vũ, Gabrielle Chan. World Premiere. Available online.

ALL DIRT ROADS TASTE OF SALT: U.S.A. (Dir/Wri: Raven Jackson – A decades-spanning exploration of a woman’s life in Mississippi and an ode to the generations of people, places, and ineffable moments that shape us. Cast: Charleen McClure, Moses Ingram, Kaylee Nicole Johnson, Reginald Helms Jr., Sheila Atim, Chris Chalk. World Premiere. Available online.

FAIR PLAY: U.S.A. Dir/Wri: Chloe Domont – An unexpected promotion at a cutthroat hedge fund pushes a young couple’s relationship to the brink, threatening to unravel far more than their recent engagement. Cast: Phoebe Dynevor, Alden Ehrenreich, Eddie Marsan. World Premiere. Available online.

FANCY DANCE: / U.S.A. Dir/Wri: Erica Tremblay, Wri: Miciana Alise – Following her sister’s disappearance, a Native American hustler kidnaps her niece from the child’s white grandparents and sets out for the state powwow in hopes of keeping what is left of their family intact. Cast: Lily Gladstone, Isabel Deroy-Olson, Ryan Begay, Shea Whigham, Audrey Wasilewski. World Premiere. Available online.

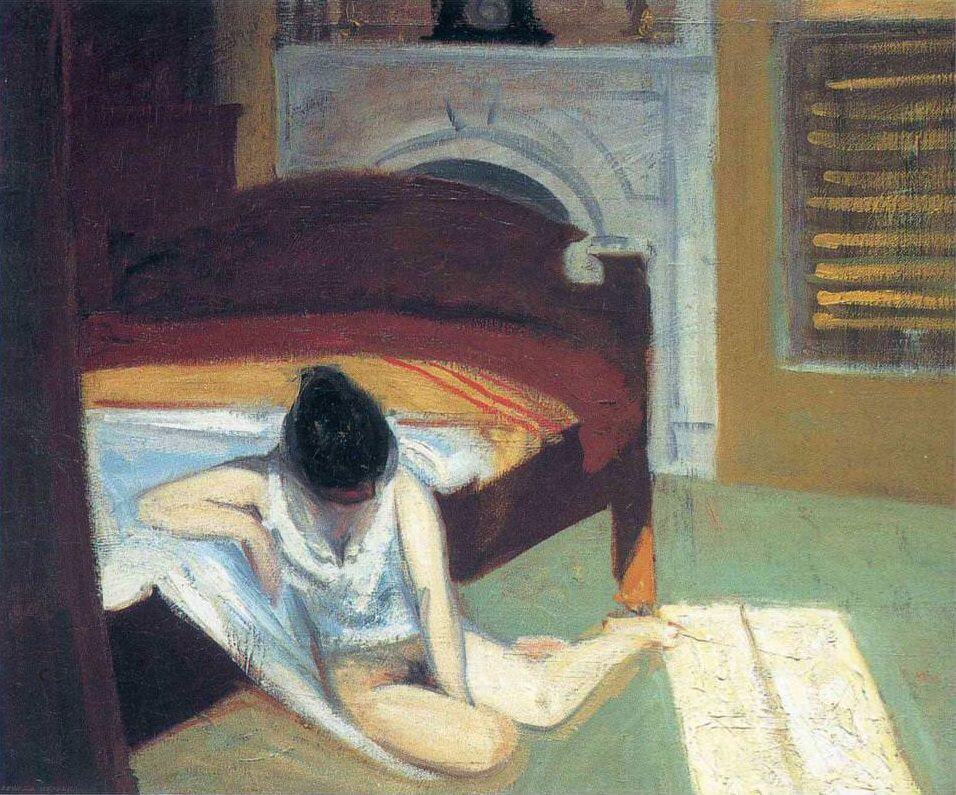

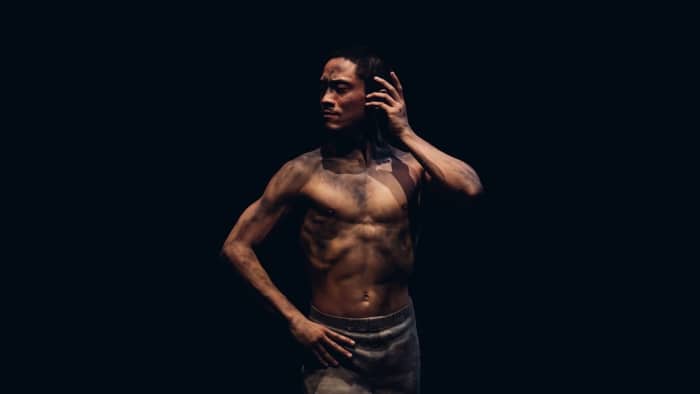

MAGAZINE DREAMS: / U.S.A. Dir/Wri: Elijah Bynum – An amateur bodybuilder struggles to find human connection as his relentless drive for recognition pushes him to the brink. Cast: Jonathan Majors, Haley Bennett, Taylour Paige, Mike O’Hearn, Harrison Page, Harriet Sansom Harris. World Premiere. Available online.

MUTT / U.S.A. (Dir/Wri: Vuk Lungulov-Klotz — Over the course of a single hectic day in New York City, three people from Feña’s past are thrust back into his life. Having lost touch since transitioning from female to male, he navigates the new dynamics of old relationships while tackling the day-to-day challenges of living life in between. Cast: Lío Mehiel, Cole Doman, MiMi Ryder, Alejandro Goic. World Premiere. Available online.

THE PERSIAN VERSION / U.S.A. Dir/Wri: Maryam Keshavarz, Producers: Anne Carey, Ben Howe, Luca Borghese, Peter Block, Corey Nelson) — When a large Iranian-American family gathers for the patriarch’s heart transplant, a family secret is uncovered that catapults the estranged mother and daughter into an exploration of the past. Toggling between the United States and Iran over decades, mother and daughter discover they are more alike than they know. Cast: Layla Mohammadi, Niousha Noor, Kamand Shafieisabet, Bella Warda, Bijan Daneshmand, Shervin Alenabi. World Premiere. Available online.

SHORTCOMINGS / U.S.A. Dir: Randall Park, Wri: Adrian Tomine — Following Ben, Miko, and Alice as they navigate a range of interpersonal relationships and traverse the country in search of the ideal connection. Cast: Justin H. Min, Sherry Cola, Ally Maki, Debby Ryan, Tavi Gevinson, Sonoya Mizuno. World Premiere. Available online.

SOMETIMES I THINK ABOUT DYING: /U.S.A. Dir: Rachel Lambert, Wri: Kevin Armento, Stefanie Abel Horowitz, Katy Wright-Mead — Fran likes to think about dying. It brings sensation to her quiet life. When she makes the new guy at work laugh, it leads to more: a date, a slice of pie, a conversation, a spark. The only thing standing in their way is Fran herself. Cast: Daisy Ridley, Dave Merheje, Parvesh Cheena, Marcia DeBonis, Meg Stalter, Brittany O’Grady. World Premiere. Available online. DAY ONE

THE STARLING GIRL / U.S.A. Dir/Wri: Laurel Akira Parmet — Seventeen-year-old Jem Starling struggles with her place within her Christian fundamentalist community, but everything changes when her magnetic youth pastor Owen returns to their church. Cast: Eliza Scanlen, Lewis Pullman, Jimmi Simpson, Wrenn Schmidt, Austin Abrams, Jessamine Burgum. World Premiere. Available online.

THEATRE CAMP / U.S.A. Dir/Wri Molly Gordon, Nick Lieberman, Screenwriters: Noah Galvin, Ben Platt — When the beloved founder of a run-down theatre camp in upstate New York falls into a coma, the eccentric staff must band together with the founder’s crypto-bro son to keep the camp afloat. Cast: Molly Gordon, Ben Platt, Noah Galvin, Jimmy Tatro, Patti Harrison, Ayo Edebiri. World Premiere. Available online.

A THOUSAND AND ONE / U.S.A. Dir/Wri: A.V. Rockwell — Convinced it’s one last, necessary crime on the path to redemption, unapologetic and free-spirited Inez kidnaps 6-year-old Terry from the foster care system. Holding on to their secret and each other, mother and son set out to reclaim their sense of home, identity, and stability in New York City. Cast: Teyana Taylor, Will Catlett, Josiah Cross, Aven Courtney, Aaron Kingsley Adetola. World Premiere. Available online.

U.S. DOCUMENTARY COMPETITION

AUM: The Cult at the End of the World /U.S.A. (Dirs: Ben Braun, Chiaki Yanagimoto — On the morning of March 20, 1995, a deadly nerve gas attack in the Tokyo subway sent the nation and its people into chaos. This exploration of Aum Shinrikyo, the cult responsible for the attack, involves the participation of those who lived through the horror as it unfolded. World Premiere. Available online.

BAD PRESS / U.S.A (Dirs: Rebecca Landsberry-Baker, Joe Peeler — When the Muscogee Nation suddenly begins censoring its free press, a rogue reporter fights to expose her government’s corruption in a historic battle that will have ramifications for all of Indian country. World Premiere. Available online.

THE DISAPPEARANCE OF SHERE HITE / U.S.A. (Dir: Nicole Newnham — Shere Hite’s 1976 bestselling book, The Hite Report, liberated the female orgasm by revealing the most private experiences of thousands of anonymous survey respondents. Her findings rocked the American establishment and presaged current conversations about gender, sexuality, and bodily autonomy. So how did Shere Hite disappear? World Premiere. Available online.

GOING TO MARS: The Nikki Giovanni Project / U.S.A. (Dir: Joe Brewster, Michèle Stephenson — Intimate vérité, archival footage, and visually innovative treatments of poetry take us on a journey through the dreamscape of legendary poet Nikki Giovanni as she reflects on her life and legacy. World Premiere. Available online.

GOING VARSITY IN MARIACHI / U.S.A. (DirS: Alejandra Vasquez, Sam Osborn — In the competitive world of high school mariachi, the musicians from the South Texas borderlands reign supreme. Under the guidance of coach Abel Acuña, the teenage captains of Edinburg North High School’s acclaimed team must turn a shoestring budget and diverse crew of inexperienced musicians into state champions. World Premiere. Available online.

JOONAM / U.S.A. (Dir: Sierra Urich — Spurred by a provocative family memory and a lifetime of separation from the country her mother left behind, a young filmmaker delves into her mother and grandmother’s complicated pasts and her own fractured Iranian identity. World Premiere. Available online.

LITTLE RICHARD: I AM EVERYTHING/ U.S.A. Dir: Lisa Cortés — This celebration of Little Richard reveals the Black queer origins of rock ’n’ roll, finally exploding the whitewashed canon of American pop music. Through archival and performance footage, the revolutionary icon’s life unspools with all of its switchbacks and contradictions. World Premiere. Available online. DAY ONE

NAM JUNE PAIK: Moon is the Oldest TV / U.S.A. (Dir: Amanda Kim — The quixotic journey of Nam June Paik, one of the most famous Asian artists of the 20th century, who revolutionised the use of technology as an artistic canvas and prophesied both the fascist tendencies and intercultural understanding that would arise from the interconnected nature of today’s world. World Premiere. Available online.

A STILL SMALL VOICE/ U.S.A. Dir: Luke Lorentzen — An aspiring hospital chaplain begins a yearlong residency in spiritual care, only to discover that to successfully tend to her patients, she must look deep within herself. World Premiere. Available online.

THE STROLL/ U.S.A. (Dir: Kristen Lovell — The history of New York’s Meatpacking District, told from the perspective of transgender sex workers who lived and worked there. Filmmaker Kristen Lovell, who walked “The Stroll” for a decade, reunites her community to recount the violence, policing, homelessness, and gentrification they overcame to build a movement for transgender rights. World Premiere. Available online.

VICTIM/SUSPECT/ U.S.A. (Dir: Nancy Schwartzman — Investigative journalist Rae de Leon travels nationwide to uncover and examine a shocking pattern: Young women tell the police they’ve been sexually assaulted, but instead of finding justice, they’re charged with the crime of making a false report, arrested, and even imprisoned by the system they believed would protect them. World Premiere. Available online.

WORLD CINEMA DRAMATIC COMPETITION

BAD BEHAVIOUR: New Zealand Dir/wri: Alice Englert — Lucy, a former child actor, seeks enlightenment at a retreat led by spiritual leader Elon while she navigates her close yet turbulent relationship with her stunt-performer daughter, Dylan. Cast: Jennifer Connelly, Ben Whishaw, Alice Englert, Ana Scotney, Dasha Nekrasova, Marlon Williams. World Premiere. Available online.

ANIMALIA / France, Morocco, Qatar Dir/Wri: Sofia Alaoui — A young, pregnant woman finds emancipation as aliens land in Morocco. Cast: Oumaïma Barid, Mehdi Dehbi, Fouad Oughaou. World Premiere. Available online.

GIRL U.K. Dir/Wri: Adura Onashile — Eleven-year-old Ama and her mother, Grace, take solace in the gentle but isolated world they obsessively create. Ama’s growing up threatens the boundaries of their tenderness and forces Grace to reckon with a past she struggles to forget. Cast: Déborah Lukumuena, Danny Sapani, Le’Shantey Bonsu, Liana Turner. World Premiere. Available online.

HEROIC – Mexico, Sweden (Dir/Wri: David Zonana — Luis, an 18-year-old boy with Indigenous roots, enters the Heroic Military College in hopes of ensuring a better future. There, he encounters a rigid and institutionally violent system designed to turn him into a perfect soldier. Cast: Santiago Sandoval Carbajal, Fernando Cuautle, Mónica del Carmen, Esteban Caicedo, Carlos Gerardo García, Isabel Yudice. World Premiere. Available online.

MAMACRUZ – Spain Dir/Wri: Patricia Ortega, Wri: José Ortuño — With the help of her newly emigrated daughter, a religious grandmother learns how to use the internet. However, an accidental encounter with pornography poses a dilemma for her. Cast: Kiti Mánver. World Premiere. Available online.

MAMI VATA – Nigeria Dir/Wri: C.J. “Fiery” Obasi — When the harmony in a village is threatened by outside elements, two sisters must fight to save their people and restore the glory of a mermaid goddess to the land. Cast: Evelyne Ily, Uzoamaka Aniunoh, Kelechi Udegbe, Emeka Amakeze, Rita Edochie, Tough Bone. World Premiere. Available online.

LA PECERA – Puerto Rico, Spain Dir/Wri: Glorimar Marrero Sánchez — As her cancer spreads, Noelia’s ultimate decision is to return to her native Vieques, Puerto Rico, and claim her freedom to decide her own fate. She reunites with her friends and family, who are still dealing with the contamination of the U.S. Navy after sixty years of military practices. Cast: Isel Rodríguez, Modesto Lacén, Magali Carrasquillo, Maximiliano Rivas, Anamín Santiago, Idenisse Salamán. World Premiere. Available online.

SCRAPPER: U.K. Dir/Wri: Charlotte Regan — Georgie is a dreamy 12-year-old girl who lives happily alone in her London flat, filling it with magic. Out of nowhere, her estranged father turns up and forces her to confront reality. Cast: Harris Dickinson, Lola Campbell, Alin Uzun, Ambreen Razia, Olivia Brady, Aylin Tezel. World Premiere. Available online.

SHAYDA – Australia (Dir/Wri: Noora Niasari — Shayda, a brave Iranian mother, finds refuge in an Australian women’s shelter with her 6-year-old daughter. Over Persian New Year, they take solace in Nowruz rituals and new beginnings, but when her estranged husband re-enters their lives, Shayda’s path to freedom is jeopardized. Cast: Zar Amir Ebrahimi, Osamah Sami, Leah Purcell, Jillian Nguyen, Mojean Aria, Selina Zahednia. World Premiere. Available online. DAY ONE

SLOW – Lithuania, Spain, Sweden (Dir/Wri: Marija Kavtaradze — Dancer Elena and sign language interpreter Dovydas meet and form a beautiful bond. As they dive into a new relationship, they must navigate how to build their own kind of intimacy. Cast: Greta Grinevičiūtė, Kęstutis Cicėnas. World Premiere. Available online.

SORCERY – Chile, Mexico, Germany Dir/Wri: Christopher Murray, Wri: Pablo Paredes — On the remote island of Chiloé in the late 19th century, an Indigenous girl named Rosa lives and works with her father on a farm. When the foreman brutally turns on Rosa’s father, she sets out for justice, seeking help from the king of a powerful organisation of sorcerers. Cast: Valentina Véliz, Daniel Antivilo, Sebastian Hulk, Daniel Muñoz. World Premiere. Available online.

WHEN IT MELTS – Belgium Dir/Wri: Veerle Baetens, Wri: Maarten Loix — Many years after a sweltering summer that spun out of control, Eva returns to the village she grew up in with an ice block in the back of her car. In the dead of winter, she confronts her past and faces up to her tormentors. Cast: Charlotte De Bruyne, Rosa Marchant. World Premiere. Available online.

WORLD CINEMA DOCUMENTARY COMPETITION

5 SEASONS OF REVOLUTION – Germany, Syria, Netherlands, Norway Dir: Lina — An aspiring video journalist in her 20s finds herself already facing self-reckoning. Born in Damascus, Syria, Lina starts to report on the events around her until she is compelled to become a war reporter and, later, the unexpected narrator of her own destiny. World Premiere. Available online.

20 DAYS IN MARIUPOL – Ukraine Dir/Wri: Mstyslav Chernov — As the Russian invasion begins, a team of Ukrainian journalists trapped in the besieged city of Mariupol struggle to continue their work documenting the war’s atrocities. World Premiere. Available online.

AGAINST THE TIDE – India Dir/Wri: Sarvnik Kaur — Two friends, both Indigenous fishermen, are driven to desperation by a dying sea. Their friendship begins to fracture as they take very different paths to provide for their struggling families. World Premiere. Available online.

THE ETERNAL BUTTERFLY – Chile Dir/Wri: Maite Alberdi — Augusto and Paulina have been together for 25 years. Eight years ago, he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. Both fear the day he no longer recognises her. World Premiere. Available online.

FANTASTIC MACHINE – Sweden, Denmark Dirs: Axel Danielson, Maximilien Van Aertryck) — From the first camera to 45 billion cameras worldwide today, the visual sociologist filmmakers widen their lens to expose both humanity’s unique obsession with the camera’s image and the social consequences that lay ahead. World Premiere. Available online.

IRON BUTTERFLIES – Ukraine, Germany Dir: Roman Liubyi — In summer 2014, sunflower fields and coal mines in eastern Ukraine turned into a 12 square kilometre crime scene. A multi-layered investigation into the downing of flight MH17, in which a butterfly-shaped shrapnel was found in the pilot’s body, implicated the state responsible for a war crime that remains unpunished. World Premiere. Available online.

IS THERE ANYBODY OUT THERE? / U.K. DIR: Ella Glendining — While navigating daily discrimination, a filmmaker who inhabits and loves her unusual body searches the world for another person like her, and explores what it takes to love oneself fiercely despite the pervasiveness of ableism. World Premiere. Available online.

THE LONGEST GOODBYE – Israel, Canada Dir: Ido Mizrahy — Social isolation affects millions of people, even Mars-bound astronauts. A savvy NASA psychologist is tasked with protecting these daring explorers. World Premiere. Available online. DAY ONE

MILISUTHANDO – South Africa Dir/Wri: Milisuthando Bongela — Set in past, present, and future South Africa — an invitation into a poetic, memory-driven exploration of love, intimacy, race, and belonging by the filmmaker, who grew up during apartheid but didn’t know it was happening until it was over. World Premiere. Available online.

PIANOFORTE – Poland Dir: Jakub Piątek — Young pianists take part in the legendary International Chopin Piano Competition. A unique chance of a lifetime, portrayed from backstage and set to Chopin’s music. World Premiere. Available online.

SMOKE SAUNA SISTERHOOD – Estonia, France, Iceland Dir: Anna Hints — In the darkness of a smoke sauna, women share their innermost secrets and intimate experiences, washing off the shame trapped in their bodies and regaining their strength through a sense of communion. World Premiere. Available online.

TWICE COLONISED – Greenland, Denmark, Canada (Dir: Lin Alluna — Renowned Inuit lawyer Aaju Peter has long fought for the rights of her people. When her son suddenly dies, Aaju embarks on a journey to reclaim her language and culture after a lifetime of whitewashing and forced assimilation. But can she both change the world and mend her own wounds? World Premiere. Available online.

NEXT

BRAVE, BURKINA! – U.S.A. Dir/Wri: Walé Oyéjidé — A Burkinabé boy flees his village and migrates to Italy. When disillusioned by heartbreak and haunted by memories of home, he travels through time in hope of regaining all he has lost. Cast: Alain Tiendrebeogo, Mousty Mbaye, Noel Minougou, Aissata Deme, Afissatou Coulibaly. World Premiere. Fiction. Available online.

DIVINITY – U.S.A. Dir/Wri: Eddie Alcazar —Two mysterious brothers abduct a mogul during his quest for immortality. Meanwhile, a seductive woman helps them launch a journey of self-discovery. Cast: Stephen Dorff, Moises Arias, Jason Genao, Karrueche Tran, Bella Thorne, Scott Bakula. World Premiere. Fiction. Available online.

FREMONT – U.S.A. Dir/Wri: Babak Jalali, Screenwriter: Carolina Cavalli — Donya works for a Chinese fortune cookie factory in San Francisco. Formerly a translator for the U.S. military in Afghanistan, she struggles to put her life back in order. In a moment of sudden revelation, she decides to send out a special message in a cookie. Cast: Anaita Wali Zada, Jeremy Allen White, Gregg Turkington. World Premiere. Fiction. Available online.

KIM’S VIDEO – U.S.A. Dir/Wri: David Redmon, Ashley Sabin — Playing with the forms and tropes of various cinema genres, the filmmaker sets off on a quest to find a legendary lost video collection of 55,000 movies in Sicily. World Premiere. Documentary. Available online. DAY ONE

KING COLE – U.S.A. Dir/Wri: Elaine McMillion Sheldon — The cultural roots of coal continue to permeate the rituals of daily life in Appalachia even as its economic power wanes. The journey of a coal miner’s daughter exploring the region’s dreams and myths, untangling the pain and beauty, as her community sits on the brink of massive change. World Premiere. Documentary. Available online.

KOKOMO CITY – U.S.A. Dir: D. Smith — Four Black transgender sex workers explore the dichotomy between the Black community and themselves, while confronting issues long avoided. World Premiere. Documentary. Available online.

TO LIVE AND DIE AND LIVE – U.S.A. Dir/Wri: Qasim Basir — Muhammad returns home to Detroit to bury his stepfather and is thrust into settling his accounts, but Muhammad’s struggles with depression and addiction may finish him before he finishes the task. Cast: Amin Joseph, Skye P. Marshall, Omari Hardwick, Cory Hardrict, Dana Gourrier, Maryam Basir. World Premiere. Fiction. Available online.

THE TUBE THIEVES – U.S.A. Dir/Wri: Alison O’Daniel — From 2011 to 2013, tubas were stolen from Los Angeles high schools. This is not a story about thieves or missing tubas. Instead, it asks what it means to listen. World Premiere. Documentary. Available online.

YOUNG. WILD. FREE – U.S.A Dir: Thembi L. Banks, Iris: Juel Taylor, Tony Rettenmaier — High school senior Brandon is drowning in responsibilities when his world is turned upside down after being robbed at gunpoint by the girl of his dreams. Cast: Algee Smith, Sanaa Lathan, Sierra Capri, Mike Epps. World Premiere. Fiction. Available online.

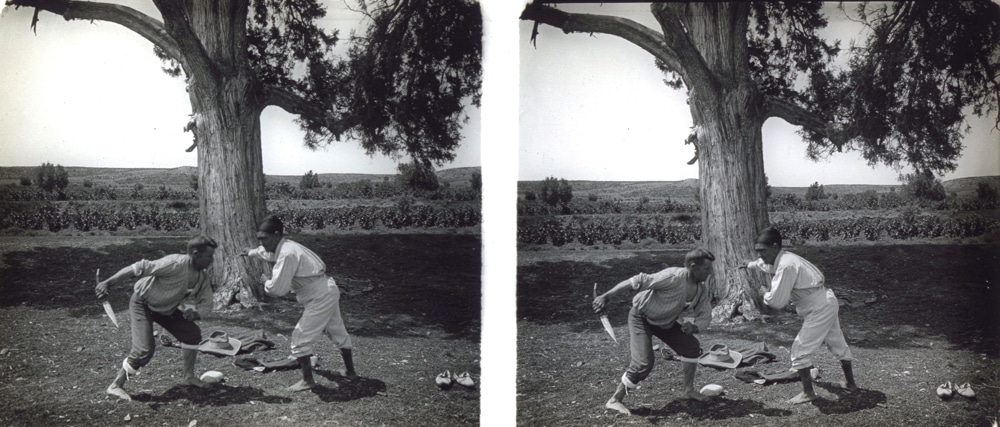

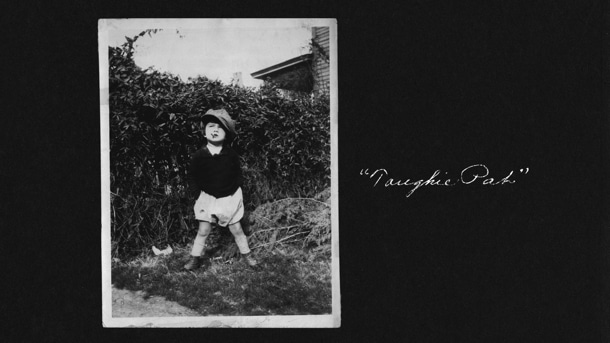

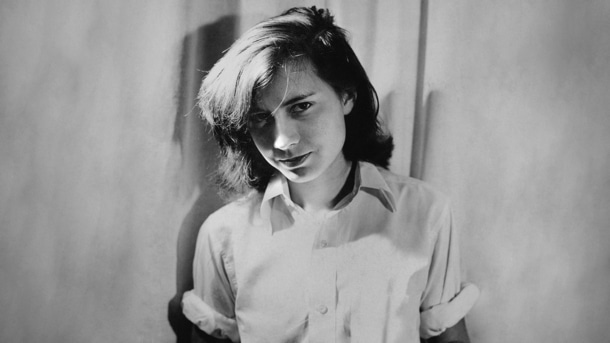

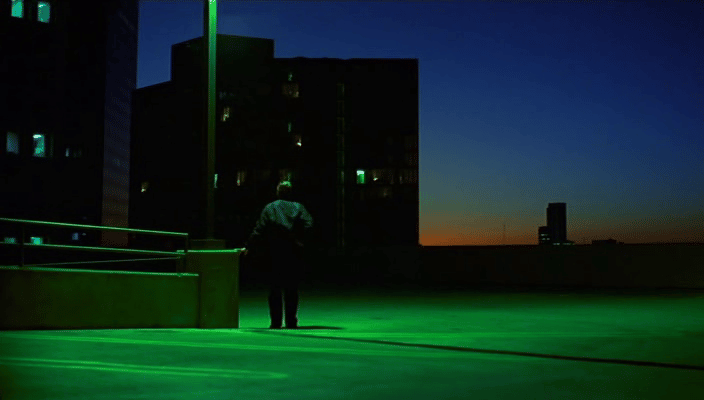

EUROPA (1931) Photo credit: Themerson Estate

EUROPA (1931) Photo credit: Themerson Estate