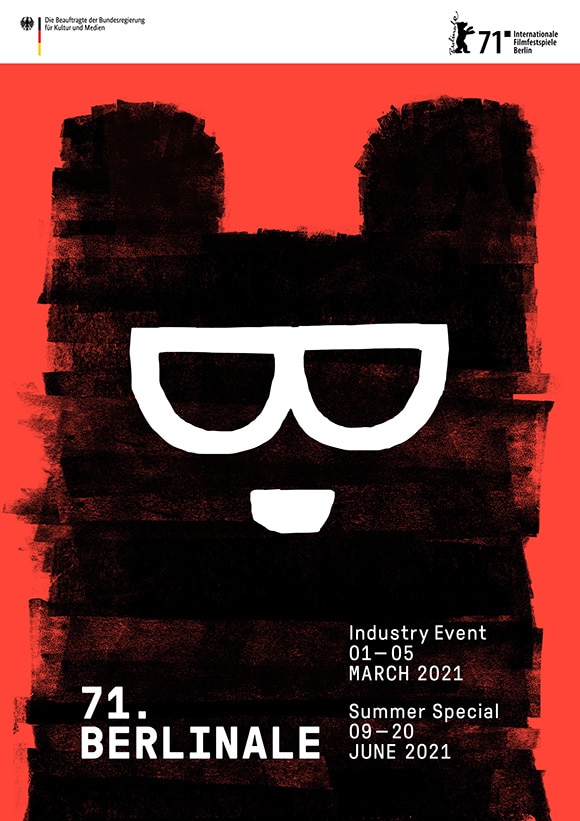

2021 gets off to a lowkey start with Sundance film festival announcing a mostly virtual edition, along with Rotterdam that follows in its footsteps on February 7th.

Sundance welcomes fewer features to this year’s line-up with 72 feature films as apposed to last year’s 118, but nearly half are female directed and 15% from the LGBTQ+ community.

Themes of retreat, regeneration and renewal are the touchstones to this year’s programme and this seems entirely appropriate given our global experience since March 2020. The world has taken stock of itself but not necessarily come up with the answers. Many film festivals are congratulating themselves for ‘increased attendance record’ with a boost from their online community. Watching films, and attending festivals online works as a complementary form of entertainment in extremis, but make no mistake, the vast majority of viewers still prefer the buzz of the festival experience and the human element that it brings.

As we stand of the brink of 2021 most of us are experiencing some sense of disconnection with our previous existence, and Robin Wright echoes this sentiment in her directorial debut, in which she also stars ,as a woman who seeks a life off grid after bereavement. Very much in the same vein as the Venice 2020 triumph Nomadland, Wright’s film Land is one of the most apposite and buzz-worthy films in the premiere lineup at this year’s Utah festival.

Sundance Institute founder and president Robert Redford is deeply aware of this social and emotional disenfranchisement and comments “Togetherness has been an animating principle here at the Sundance Institute as we’ve worked to reimagine the festival for 2021, because there is no Sundance without our community,”

And this sentiment resonates through the competition line-up. with other narrative features directly alluding to the tragedy that has affected, possibly more than we realise going forward.

A list of films confirmed for the 2021 Sundance Film Festival are as follows.

World Cinema Dramatic Competition

The Dog Who Wouldn’t Be Quiet | Argentina (Dir: Ana Katz, writers: Ana Katz, Gonzalo Delgado | World Premiere

Sebastian, a man in his 30s, works a series of temporary jobs and he embraces love at every opportunity. He transforms, through a series of short encounters, as the world flirts with possible apocalypse. Cast: Daniel Katz, Julieta Zylberberg, Valeria Lois, Mirella Pascual, Carlos Portaluppi.

Passing / UK/US (Dir/wri: Rebecca Hall | World Premiere

Based on the 19th century novel by Chicago born writer Nella Larsen, this first feature for Rebecca Hall sees two high old school friends reunited in a mutual obsession that threatens both of their carefully constructed realities.

El Planeta / US/Spain (Dir/Wri Amalia Ulman | World Premiere

Amid the devastation of post-crisis Spain, mother and daughter bluff and grift to keep up the lifestyle they think they deserve, bonding over common tragedy and an impending eviction. Cast: Amalia Ulman, Ale Ulman, Nacho Vigalondo, Zhou Chen, Saoirse Bertram.

Fire in the Mountains / India (Dir/Wri: Ajitpal Singh | World Premiere

A mother toils to save money to build a road in a Himalayan village to take her wheelchair-bound son for physiotherapy, but her husband, who believes that an expensive religious ritual is the remedy, steals her savings. Cast: Vinamrata Rai, Chandan Bisht, Mayank Singh Jaira, Harshita Tewari, Sonal Jha.

Hive / Kos, Switzerland, Macedonia, Albania (Dir/Wri: Blerta Basholli | World Premiere

Fahrije’s husband has been missing since the war in Kosovo. She sets up her own small business to provide for her kids, but as she fights against a patriarchal society that does not support her, she faces a crucial decision: to wait for his return, or to continue to persevere. Cast: Yllka Gashi, Çun Lajçi, Aurita Agushi, Kumrije Hoxha, Adriana Matoshi, Kaona Sylejmani.

Human Factors / Ger, Italy, Denmark (Dir/Wri: Ronny Trocker | World Premiere

A mysterious housebreaking exposes the agony of an exemplary middle-class family. Cast: Sabine Timoteo, Mark Waschke, Jule Hermann, Wanja Valentin Kube, Hannes Perkmann, Daniel Séjourné.

Luzzu / Malta (Dir/Wri): Alex Camilleri | World Premiere

Jesmark, a struggling fisherman on the island of Malta, is forced to turn his back on generations of tradition and risk everything by entering the world of black-market fishing to provide for his girlfriend and newborn baby. Cast: Jesmark Scicluna, Michela Farrugia, David Scicluna.

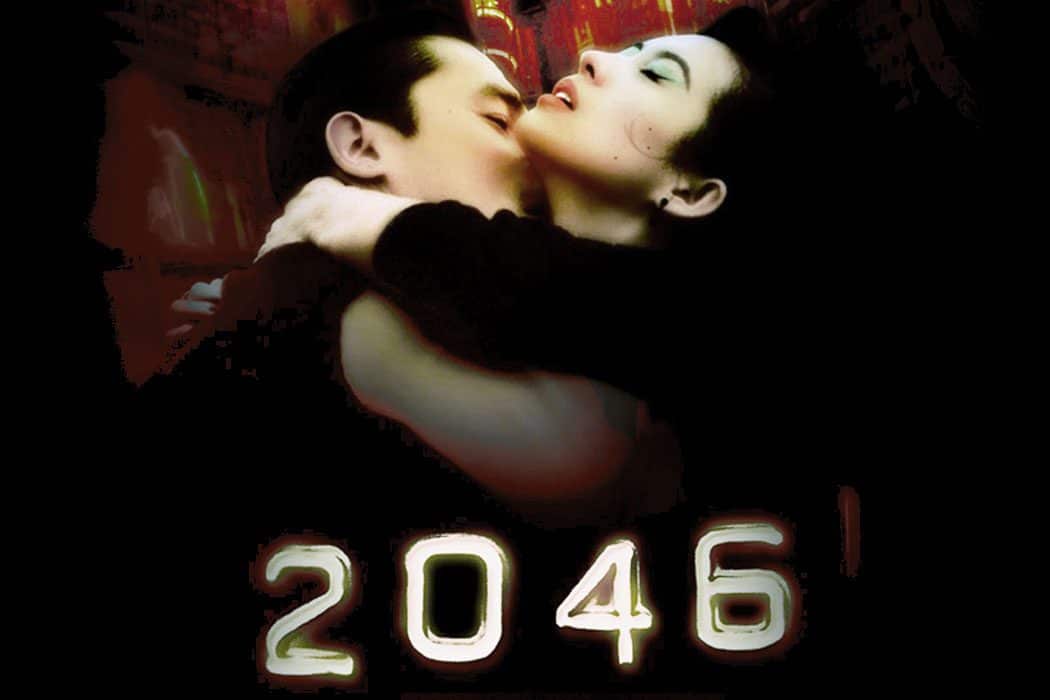

One for the Road / China,Hong Kong, Thailand (Dir: Baz Poonpiriya, Wri: Baz Poonpiriya, Nottapon Boonprakob, Puangsoi Aksornsawang, Wong Kar Wai) | World Premiere

Boss is a consummate ladies’ man, a free spirit and a bar owner in NYC. One day, he gets a surprise call from Aood, an estranged friend who has returned home to Thailand. Dying of cancer, Aood enlists Boss’ help to complete a bucket list — but both are hiding something. Cast: Tor Thanapob, Ice Natara, Violette Wautier, Aokbab Chutimon, Ploi Horwang, Noon Siraphun.

The Pink Cloud / Brazil (Dir/Wri: Iuli Gerbase, | World Premiere

A mysterious and deadly pink cloud appears across the globe, forcing everyone to stay home. Strangers at the outset, Giovana and Yago try to invent themselves as a couple as years of shared lockdown pass. While Yago is living in his own utopia, Giovana feels trapped deep inside. Cast: Renata de Lélis, Eduardo Mendonça.

Pleasure / Swed/Neth/France (Dir,Wri: Ninja Thyberg | World Prem

A 20-year-old girl moves from her small town in Sweden to L.A. for a shot at a career in the adult film industry. Cast: Sofia Kappel, Revika Anne Reustle, Evelyn Claire, Chris Cock, Dana DeArmond, Kendra Spade.

Prime Time / Poland (Dir: Jakub Piątek, Writers: Jakub Piątek, Lukasz Czapski | World Premierę

On the last day of 1999, 20-year-old Sebastian locks himself in a TV studio. He has two hostages, a gun and an important message for the world. The story of the attack explores a rebel’s extreme measures and last resort. Cast: Bartosz Bielenia, Magdalena Poplawska, Andrzej Klak, Malgorzata Hajewska-Krzysztofik, Dobromir Dymecki, Monika Frajczyk.

World Cinema Documentary Competition

Faya Dayi / Ethiopia/US (Dir/Wri: Jessica Beshir) | World Premiere

A spiritual journey into the highlands of Harar, immersed in the rituals of khat, a leaf Sufi Muslims chewed for centuries for religious meditations — and Ethiopia’s most lucrative cash crop today. A tapestry of intimate stories offers a window into the dreams of youth under a repressive regime.

Flee / Den/Norway/Sweden/France (Dir Jonas Poher Rasmussen | World Premiere

Amin arrived as an unaccompanied minor in Denmark from Afghanistan. Today, he is a successful academic and is getting married to his longtime boyfriend. A secret he has been hiding for 20 years threatens to ruin the life he has built. W

Inconvenient Indian | Canada (Dir/Wri: Michelle Latimer | International premiere

An examination of Thomas King’s brilliant dismantling of North America’s colonial narrative, which reframes history with the powerful voices of those continuing the tradition of Indigenous resistance.

Misha and the Wolves

United Kingdom, Belgium (Dir/Wri: Sam Hobkinson) | World Premiere

A woman’s Holocaust memoir takes the world by storm, but a fallout with her publisher turned detective reveals her story as an audacious deception created to hide a darker truth.

The Most Beautiful Boy in the World / Sweden (Dir: Kristina Lindström, Kristian Petri | World Premiere

Swedish actor/musician Björn Andresen’s life was forever changed at the age of 15, when he played Tadzio, the object of Dirk Bogarde’s obsession in Death in Venice — a role that led Italian maestro Luchino Visconti to dub him “the world’s most beautiful boy.”

Playing With Sharks / Australia (Dir/Wri: Sally Aitken | World Premier

Valerie Taylor is a shark fanatic and an Australian icon — a marine maverick who forged her way as a fearless diver, cinematographer and conservationist. She filmed the real sharks for Jaws and famously wore a chainmail suit, using herself as shark bait, changing our scientific understanding of sharks forever.

President / Denmark/US, Norway (Dir: Camilla Nielsson | World Premiere

Zimbabwe is at a crossroads. The leader of the opposition MDC party, Nelson Chamisa, challenges the old guard ZANU-PF led by Emmerson Mnangagwa, known as “The Crocodile.” The election tests both the ruling party and the opposition — how do they interpret principles of democracy in discourse and in practice?

Sabaya / Sweden (Dir/Wri: Hogir Hirori | World Premiere

With just a mobile phone and a gun, Mahmud, Ziyad and their group risk their lives trying to save Yazidi women and girls being held by ISIS as Sabaya (abducted sex slaves) in the most dangerous camp in the Middle East, Al-Hol in Syria

Taming the Garden / Swit/Ger, Georgia (Dir: Salomé Jashi | World Premiere

A poetic ode to the rivalry between men and nature. World Premiere

Writing With Fire / India (Dir/Wris: Rintu Thomas, Sushmit Ghosh | World Premiere

In a cluttered news landscape dominated by men, emerges India’s only newspaper run by Dalit women. Armed with smartphones, chief reporter Meera and her journalists break traditions on the front lines of India’s biggest issues and within the confines of their own homes, redefining what it means to be powerful.

The Blazing World / U.S.A. (Dir: Carlson Young, Wri: Carlson Young, Pierce Brown | World Premiere

Decades after the accidental drowning of her twin sister, a self-destructive young woman returns to her family home, finding herself drawn to an alternate dimension where her sister may still be alive. Cast: Udo Kier, Carlson Young, Dermot Mulroney, Vinessa Shaw, John Karna, Soko.

Cryptozoo / US (Dir/Wr: Dash Shaw) | World Premiere

As cryptozookeepers struggle to capture a Baku (a legendary dream-eating hybrid creature) they begin to wonder if they should display these rare beasts in the confines of a cryptozoo, or if these mythical creatures should remain hidden and unknown. Cast: Lake Bell, Michael Cera, Angeliki Papoulia, Zoe Kazan, Peter Stormare, Grace Zabriskie

First Date / US. (Dir/Wri: Manuel Crosby, Darren Knapp | World Premiere

Conned into buying a shady ’65 Chrysler, Mike’s first date with the girl next door, Kelsey, implodes as he finds himself targeted by criminals, cops and a crazy cat lady. A night fueled by desire, bullets and burning rubber makes any other first date seem like a walk in the park. Cast: Tyson Brown, Shelby Duclos, Jesse Janzen, Nicole Berry, Ryan Quinn Adams, Brandon Kraus.

Ma Belle, My Beauty / US., France (Dir/Wri: Marion Hill | World Premiere

A surprise reunion in southern France reignites passions and jealousies between two women who were formerly polyamorous lovers. Cast: Idella Johnson, Hannah Pepper, Lucien Guignard, Sivan Noam Shimon.

R#J / US (Dir/Wri Carey William | World Premiere

A reimagining of Romeo and Juliet, taking place through their cellphones, in a mash-up of Shakespearean dialogue with current social media communication. Cast: Camaron Engels, Francesca Noel, David Zayas, Diego Tinoco, Siddiq Saunderson, Russell Hornsby.

Searchers / US. (Dir: Pacho Velez | World Premiere

In encounters alternately humorous and touching, a diverse set of New Yorkers navigate their preferred dating apps in search of their special someone.

Strawberry Mansion / US (Dir/Wri: Albert Birney, Kentucker Audley | World Premiere

In a world where the government records and taxes dreams, an unassuming dream auditor gets swept up in a cosmic journey through the life and dreams of an aging eccentric named Bella. Together, they must find a way back home. Cast: Penny Fuller, Kentucker Audley, Grace Glowicki, Reed Birney, Linas Phillips, Constance Shulman.

We’re All Going to the World’s Fair / US (Dir/Wri: Jane Schoenbrun | World Premiere

A teenage girl becomes immersed in an online role-playing game. Cast: Anna Cobb, Michael J. Rogers.

Amy Tan: Unintended Memoir / US. (Director: James Redford | World Premiere

Amy Tan has established herself as one of America’s most respected literary voices. Born to Chinese immigrant parents, it would be decades before the author of The Joy Luck Club would fully understand the inherited trauma rooted in the legacies of women who survived the Chinese tradition of concubinage.

Bring Your Own Brigade / US. (Dir/wri: Lucy Walker | World Premiere

A character-driven verité and revelatory investigation takes us on a journey embedded with firefighters and residents on a mission to understand the causes of historically large wildfires and how to survive them, discovering that the solution has been here all along.

Eight for Silver / U.S.A., France (Dir/Wri Sean Ellis | World Premiere

In the late 1800s, a man arrives in a remote country village to investigate an attack by a wild animal but discovers a much deeper, sinister force that has both the manor and the townspeople in its grip. Cast: Boyd Holbrook, Kelly Reilly, Alistair Petrie, Roxane Duran, Aine Rose Daly.

How It Ends / US (Dir/Wri Daryl Wein, Zoe Lister-Jones | World Premiere

On the last day on Earth, one woman goes on a journey through L.A. to make it to her last party before the world ends, running into an eclectic cast of characters along the way. Cast: Zoe Lister-Jones, Cailee Spaeny, Olivia Wilde, Fred Armisen, Helen Hunt, Lamorne Morris.

In the Earth / UK (Dir/Wri: Ben Wheatley | World Premiere

As a disastrous virus grips the planet, a scientist and a park scout venture deep into the forest for a routine equipment run. Through the night, their journey becomes a terrifying voyage through the heart of darkness as the forest comes to life around them. Cast: Joel Fry, Ellora Torchia, Hayley Squires, Reece Shearsmith

In the Same Breath / US. (Dir: Nanfu Wang) | World Premiere

How did the Chinese government turn pandemic coverups in Wuhan into a triumph for the Communist party? An essential narrative of firsthand accounts of the novel coronavirus, and a revelatory examination of how propaganda and patriotism shaped the outbreak’s course — both in China and in the U.S. World Premiere, Documentary. DAY ONE

Marvelous and the Black Hole / US (Dir/Wri Kate Tsang, Producer | World Premiere

A teenage delinquent befriends a surly magician who helps her navigate her inner demons and dysfunctional family with sleight of hand magic, in a coming-of-age comedy that touches on unlikely friendships, grief and finding hope in the darkest moments. Cast: Miya Cech, Rhea Perlman, Leonardo Nam, Kannon Omachi, Paulina Lule, Keith Powell.

Mass / US (Dir/Wri: Fran Kranz | World Premiere

Years after a tragic shooting, the parents of both the victim and the perpetrator meet face to face. Cast: Jason Isaacs, Ann Dowd, Martha Plimpton, Reed Birney.

My Name Is Pauli Murray / US (Dirs: Betsy West, Julie Cohen |World premiere

Overlooked by history, Pauli Murray was a legal trailblazer whose ideas influenced RBG’s fight for gender equality and Thurgood Marshall’s landmark civil rights arguments. Featuring never-before-seen footage and audio recordings, a portrait of Murray’s impact as a nonbinary Black luminary: lawyer, activist, poet and priest who transformed our world.

Philly D.A. / US. (Dirs: Ted Passon, Yoni Brook | World Premiere

A groundbreaking inside look at the long-shot election and tumultuous first term of Larry Krasner, Philadelphia’s unapologetic district attorney, and his experiment to upend the criminal justice system from the inside out.

Prisoners of the Ghostland / US. (Dir: Sion Sono, Wri: Aaron Hendry, Reza Sixo Safai | World Premiere

A notorious criminal is sent to rescue an abducted woman who has disappeared into a dark supernatural universe. They must break the evil curse that binds them and escape the mysterious revenants that rule the Ghostland, an East-meets-West vortex of beauty and violence. Cast: Nicolas Cage, Sofia Boutella, Nick Cassavetes, Bill Moseley, Tak Sakaguchi, Yuzuka Nakaya.

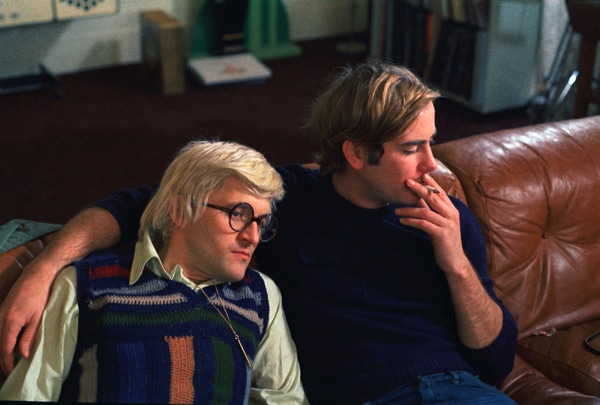

The Sparks Brothers / UK (Dir: Edgar Wright | World Premiere

How can one rock band be successful, underrated, hugely influential and criminally overlooked all at the same time? Take a musical odyssey through five weird and wonderful decades with brothers Russell & Ron Mael, celebrating the inspiring legacy of Sparks: your favorite band’s favourite band.

Street Gang: How We Got to Sesame Street / US. (Dir/: Marilyn Agrelo | World Premiere

How did a group of rebels create the world’s most famous street? In 1969 New York, this “gang” of mission-driven artists, writers and educators catalyzed a moment of civil awakening, transforming it into Sesame Street, one of the most influential and impactful television programs in history.

Midnight

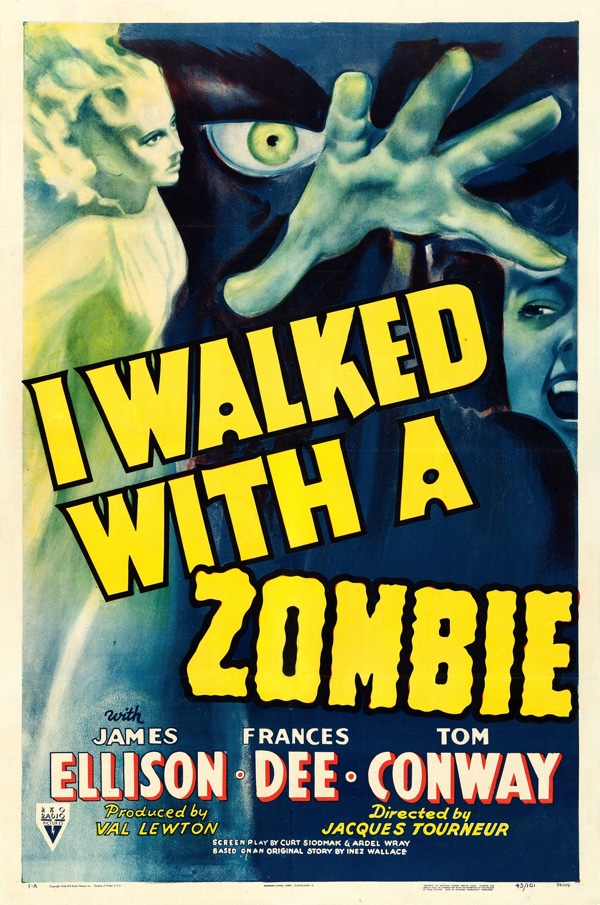

Censor / UK (Dir/Wri: Prano Bailey-Bond, Aris: Prano Bailey-Bond, Anthony Fletcher | World Premiere

When film censor Enid discovers an eerie horror that speaks directly to her sister’s mysterious disappearance, she resolves to unravel the puzzle behind the film and its enigmatic director — a quest blurring the lines between fiction and reality in terrifying ways. Cast: Niamh Algar, Nicholas Burns, Vincent Franklin, Sophia La Porta, Adrian Schiller, Michael Smiley.

Coming Home in the Dark / NZ (Dir: James Ashcroft, Wri: Eli Kent, James Ashcroft | World Premiere

A family’s outing descends into terror when teacher Alan Hoaganraad, his wife Jill, and stepsons Maika and Jordon explore an isolated coastline. An unexpected meeting with a pair of drifters, the enigmatic psychopath Mandrake and his accomplice Tubs, thrusts the family into a nightmare when they find themselves captured. Cast: Daniel Gillies, Erik Thomson, Miriama McDowell, Matthias Luafutu.

A Glitch in the Matrix / US (Dir Rodney Ascher | World Premiere

A multimedia exploration of simulation theory — an idea as old as Plato’s Republic and as current as Elon Musk’s Twitter feed — through the eyes of those who suspect our world isn’t real. Part sci-fi mind-scrambler, part horror story, this is a digital journey to the limits of radical doubt.

Knocking / Sweden (Dir: Frida Kempff, Wri: Emma Broström | World Premiere

When Molly moves into her new apartment after a tragic accident, a strange noise from upstairs begins to unnerve her. As its intensity grows, she confronts her neighbors — but no one seems to hear what she is hearing. Cast: Cecilia Milocco.

Mother Schmuckers / Belgium (Dir/Wri: Lenny Guit, Harpo Guit | World Premiere

Issachar & Zabulon, two brothers in their 20s, are supremely stupid and never bored, as madness is part of their daily lives. When they lose their mother’s beloved dog, they have 24 hours to find it — or she will kick them out. Cast: Harpo Guit, Maxi Delmelle, Claire Bodson, Mathieu Amalric, Habib Ben Tanfous.

Special Screenings

Life in a Day 2020 / US/UK. (Dir: Kevin Macdonald | World Premier

An extraordinary, intimate, global portrait of life on our planet, filmed by thousands of people across the world, on a single day: 25th July 2020.

Sundance Film Festival | 28 January – 3 February 2021

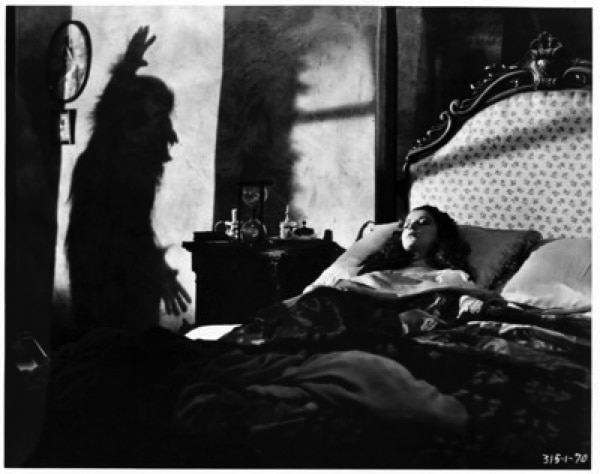

Atmospherically directed by Hungarian Peter Sasdy, and adapted for the screen by Anthony Hinds – stepping in due to budgetary constraints under the pseudonym of John Elder (he told his neighbours he was a hairdresser to avoid publicity throughout his entire career) this outing actually broadens the storyline into a damning social satire of Victorian repression and upper class ennui. The eclectic cast has Christopher Lee, Geoffrey Keen and Gwen Watford and sees three distinguished English gentlemen (Keen, Peter Sallis and John Carson) descend into Satanism, for want of anything better to do, accidentally killIng Dracula‘s sidekick Lord Courtly (Ralph Bates), in the process. As an act of revenge the Count vows they will die at the hands of their own children. But Lee actually bloodies the waters in the second half, swanning in glowering due to his lack of a domineering role in the proceedings.

Atmospherically directed by Hungarian Peter Sasdy, and adapted for the screen by Anthony Hinds – stepping in due to budgetary constraints under the pseudonym of John Elder (he told his neighbours he was a hairdresser to avoid publicity throughout his entire career) this outing actually broadens the storyline into a damning social satire of Victorian repression and upper class ennui. The eclectic cast has Christopher Lee, Geoffrey Keen and Gwen Watford and sees three distinguished English gentlemen (Keen, Peter Sallis and John Carson) descend into Satanism, for want of anything better to do, accidentally killIng Dracula‘s sidekick Lord Courtly (Ralph Bates), in the process. As an act of revenge the Count vows they will die at the hands of their own children. But Lee actually bloodies the waters in the second half, swanning in glowering due to his lack of a domineering role in the proceedings.

Green’s female engineer Sarah is at the heart of Proxima. She is a luminous presence – fragile tough and strangely otherworldly. Given the opportunity to join the European Space Agency’s Mars probe mission along with other seasoned spacemen – including Matt Dillon’s macho but golden-hearted leader – she takes the plunge. What starts out as matter of fact preparation for the long term mission soon becomes a fraught and increasingly affecting exploration of what is means to love, to be a parent, to meet professional goals, and to thrive and appreciate our own planet. Proxima is a ground-breaking and beautiful film as much about our life here on Earth as is about this perilous journey into the unknown.

Green’s female engineer Sarah is at the heart of Proxima. She is a luminous presence – fragile tough and strangely otherworldly. Given the opportunity to join the European Space Agency’s Mars probe mission along with other seasoned spacemen – including Matt Dillon’s macho but golden-hearted leader – she takes the plunge. What starts out as matter of fact preparation for the long term mission soon becomes a fraught and increasingly affecting exploration of what is means to love, to be a parent, to meet professional goals, and to thrive and appreciate our own planet. Proxima is a ground-breaking and beautiful film as much about our life here on Earth as is about this perilous journey into the unknown.

Larger and much stranger than life, director/producer Matt Wolf (

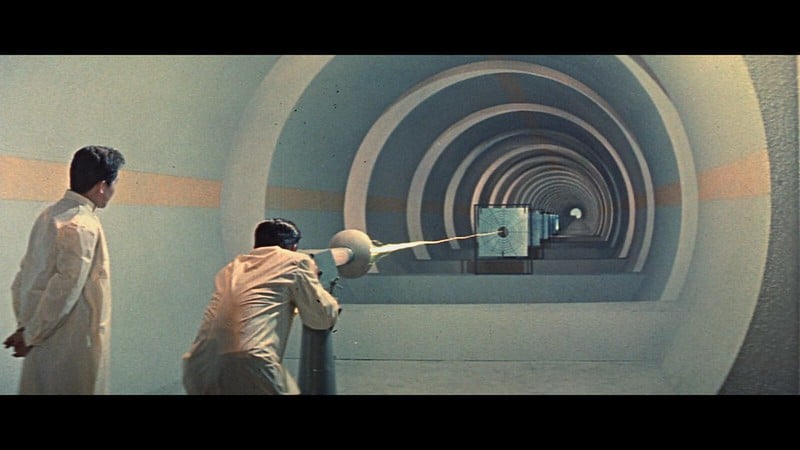

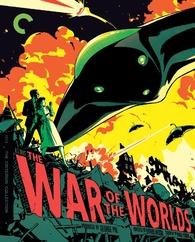

Larger and much stranger than life, director/producer Matt Wolf ( Although a brash travesty of H.G.Wells’ original 1898 novel, and despite Steven Spielberg’s 2005 ‘upgrade’ and last autumn’s well-received TV version, George Pal’s original big screen version is still for many the last word in fifties Technicolor destruction on the grand scale (blessed as John Baxter described it with “the smooth unreality of a comic strip”).

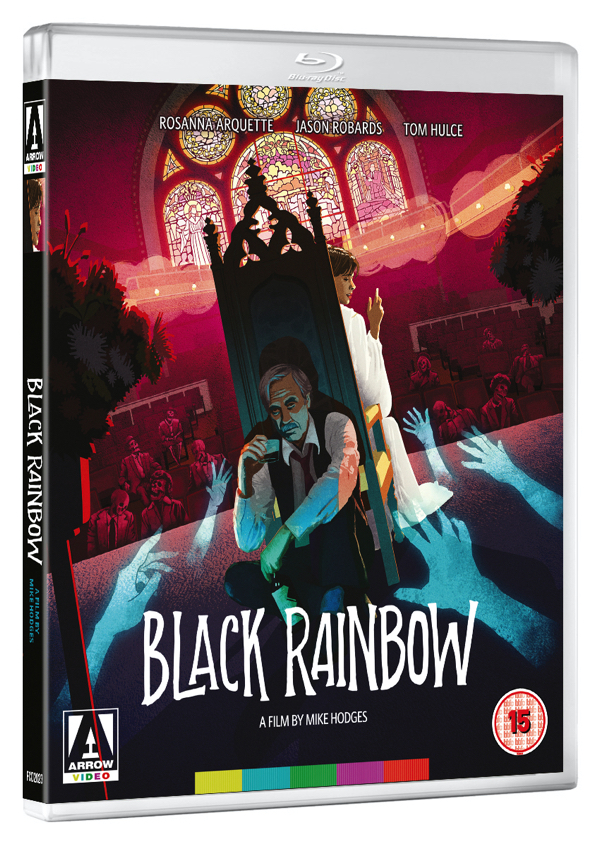

Although a brash travesty of H.G.Wells’ original 1898 novel, and despite Steven Spielberg’s 2005 ‘upgrade’ and last autumn’s well-received TV version, George Pal’s original big screen version is still for many the last word in fifties Technicolor destruction on the grand scale (blessed as John Baxter described it with “the smooth unreality of a comic strip”). Rosanna Arquette shines as a clairvoyant on tour with her father (Jason Robards) in this supernatural curio from undervalued English director Mike Hodges.

Rosanna Arquette shines as a clairvoyant on tour with her father (Jason Robards) in this supernatural curio from undervalued English director Mike Hodges. Filtering the darkest, most dramatic period of modern Jewish history through the instinctive gaze of a dog was an ambitious idea for the best selling Israeli author Asher Kravitz. So Lynn Roth’s efforts to accommodate a young audience in her screen version are laudable but the upshot often cringeworthy.

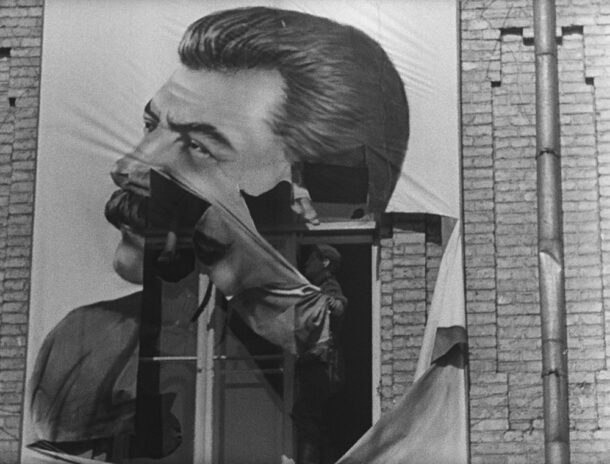

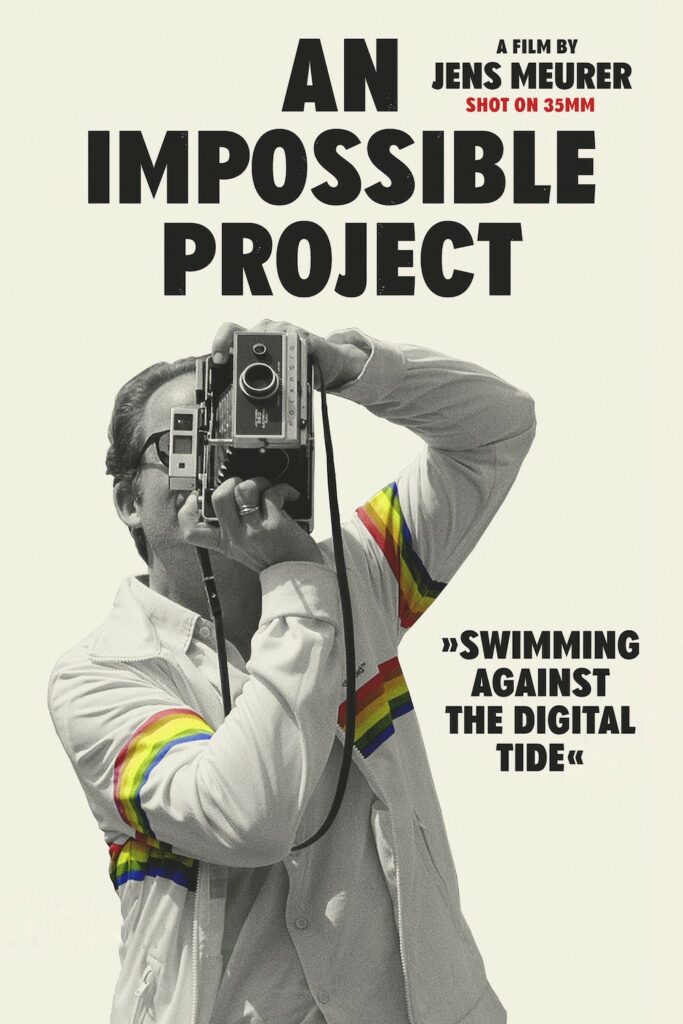

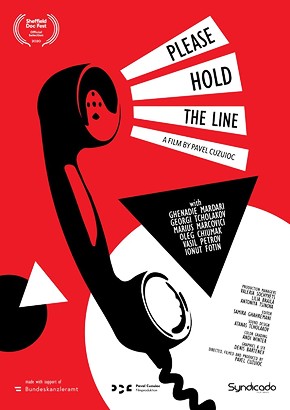

Filtering the darkest, most dramatic period of modern Jewish history through the instinctive gaze of a dog was an ambitious idea for the best selling Israeli author Asher Kravitz. So Lynn Roth’s efforts to accommodate a young audience in her screen version are laudable but the upshot often cringeworthy. The past and the present collide in this darkly amusing deep dive into the human side of the digital age. And each are as complex as the other according to Pavel Cuzuoic, whose third documentary works on two levels: As an abstract expressionist arthouse piece and a deadpan social and political satire. What emerges is a priceless look at a society in flux in Bulgaria, Romania, Moldova and Ukraine. The old fights with the new, refusing to give in.

The past and the present collide in this darkly amusing deep dive into the human side of the digital age. And each are as complex as the other according to Pavel Cuzuoic, whose third documentary works on two levels: As an abstract expressionist arthouse piece and a deadpan social and political satire. What emerges is a priceless look at a society in flux in Bulgaria, Romania, Moldova and Ukraine. The old fights with the new, refusing to give in.

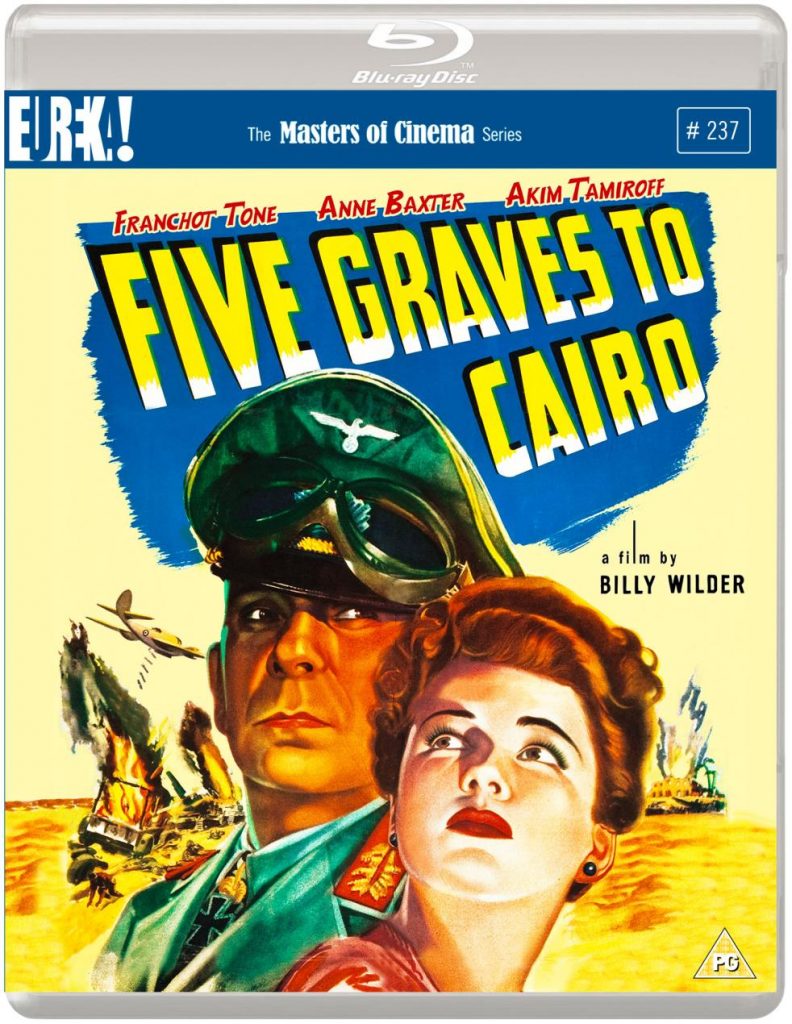

Shot in post war Berlin, the ruins of the divided capital a startling sign of the times, A Foreign Affair reunited Billy Wilder (1906-2002) with his star Marlene Dietrich. Both had met in Berlin in 1929, when Wilder interviewed Dietrich, who had a part in George Kaiser’s musical revue ‘Two Ties’ – the same year Wilder collaborated with Robert Siodmak and Fred Zinnemann (among others) for

Shot in post war Berlin, the ruins of the divided capital a startling sign of the times, A Foreign Affair reunited Billy Wilder (1906-2002) with his star Marlene Dietrich. Both had met in Berlin in 1929, when Wilder interviewed Dietrich, who had a part in George Kaiser’s musical revue ‘Two Ties’ – the same year Wilder collaborated with Robert Siodmak and Fred Zinnemann (among others) for

Mangrove, Steve McQueen (UK), 2h04′

Mangrove, Steve McQueen (UK), 2h04′ Last Words, Jonathan Nossiter (USA)

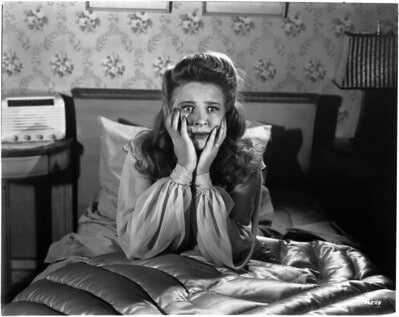

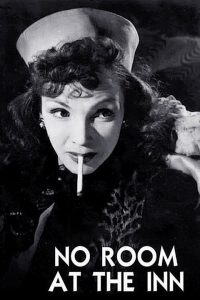

Last Words, Jonathan Nossiter (USA) A sense of the Gothic also infiltrates No Room at the Inn set in the early months of 1940. We witness atmospheric blitzed streets by the railway bridge next to a rundown house that’s definitely on the wrong side of the tracks: all lorded over by Mrs Agatha Voray (Freda Jackson) doing her damn best not to properly look after three young girl evacuees. The children live in squalor and suffer mental and physical abuse under the care of this coarse woman who invites men (local councillors and shopkeepers) for casual sex and bit of cash to bolster her shopping allowance of ration coupons.

A sense of the Gothic also infiltrates No Room at the Inn set in the early months of 1940. We witness atmospheric blitzed streets by the railway bridge next to a rundown house that’s definitely on the wrong side of the tracks: all lorded over by Mrs Agatha Voray (Freda Jackson) doing her damn best not to properly look after three young girl evacuees. The children live in squalor and suffer mental and physical abuse under the care of this coarse woman who invites men (local councillors and shopkeepers) for casual sex and bit of cash to bolster her shopping allowance of ration coupons.

Dir.: Georgui Balabanov; Documentary with Christo, Jeanne-Claude, Anani Yavashev; Bulgaria 1996, 72 min.

Dir.: Georgui Balabanov; Documentary with Christo, Jeanne-Claude, Anani Yavashev; Bulgaria 1996, 72 min.

The inspirational tenet of the Cistercian monks is simplicity. Life in a monastery is not an escape route from the world. Apart from running the monastery and brewing, the monks lives are spent in deep contemplation, silencing their minds and stripping back their own desires and thoughts and offer themselves to God in prayer. Not to be confused with meditation that has as its focus green fields, beaches or or the next holiday: the monks are taught to empty their minds so as to make room for God’s presence. Their existence is enriched by the simplicity of their lives and not their material wealth.

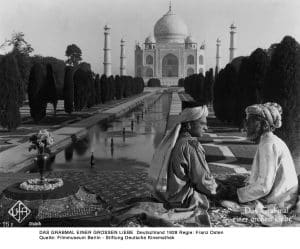

The inspirational tenet of the Cistercian monks is simplicity. Life in a monastery is not an escape route from the world. Apart from running the monastery and brewing, the monks lives are spent in deep contemplation, silencing their minds and stripping back their own desires and thoughts and offer themselves to God in prayer. Not to be confused with meditation that has as its focus green fields, beaches or or the next holiday: the monks are taught to empty their minds so as to make room for God’s presence. Their existence is enriched by the simplicity of their lives and not their material wealth. Shiraz is a fictitious character, the son of a local potter who rescues a baby girl from the wreckage of a caravan laden with treasures, ambushed while transporting her mother, a princess. Shiraz is unaware of Selima’s royal blood and he falls madly in love with her as the two grow up in their simple surroundings, until she is kidnapped and sold to Prince Khurram of Agra (a sultry Charu Roy). Shiraz then risks his life to be near her in Agra as the Prince also falls for her charms.

Shiraz is a fictitious character, the son of a local potter who rescues a baby girl from the wreckage of a caravan laden with treasures, ambushed while transporting her mother, a princess. Shiraz is unaware of Selima’s royal blood and he falls madly in love with her as the two grow up in their simple surroundings, until she is kidnapped and sold to Prince Khurram of Agra (a sultry Charu Roy). Shiraz then risks his life to be near her in Agra as the Prince also falls for her charms. Apart from being gorgeously sensual (there is a highly avantgarde kissing scene ) and gripping throughout, SHIRAZ is also an important film in that it united the expertise of three countries: Rai’s Great Eastern Indian Corporation; UK’s British Instructional Films (who also produced Anthony Asquith’s Shooting Stars and Underground in 1928) and the German Emelka Film company. Contemporary sources tell of “a serious attempt to bring India to the screen”. Attention to detail was paramount with an historical expert overseeing the sumptuous costumes, furnishings and priceless jewels that sparkle within the Fort of Agra and its palatial surroundings. Glowing in silky black and white SHIRAZ is one of the truly magical films in recent memory. MT

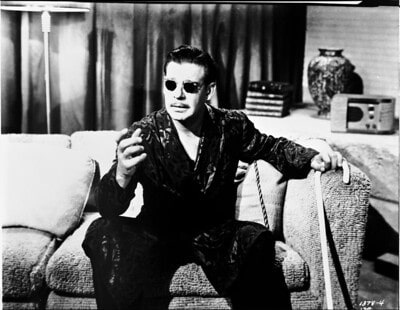

Apart from being gorgeously sensual (there is a highly avantgarde kissing scene ) and gripping throughout, SHIRAZ is also an important film in that it united the expertise of three countries: Rai’s Great Eastern Indian Corporation; UK’s British Instructional Films (who also produced Anthony Asquith’s Shooting Stars and Underground in 1928) and the German Emelka Film company. Contemporary sources tell of “a serious attempt to bring India to the screen”. Attention to detail was paramount with an historical expert overseeing the sumptuous costumes, furnishings and priceless jewels that sparkle within the Fort of Agra and its palatial surroundings. Glowing in silky black and white SHIRAZ is one of the truly magical films in recent memory. MT Valmond Maurice Guest (1911-2006) was an English film director and screenwriter who started his career on the British stage and in early sound films. He wrote over 70 scripts many of which he also directed, developing a versatile talent for making quality genre fare on a limited budget (Hell is a City, Casino Royale, The Boys in Blue). But Guest was best known for his Hammer horror pictures The Quatermass Xperiment and Quatermass II, and Sci-Fis The Day the Earth Caught Fire and 80,000 Suspects which nowadays provide a fascinating snapshot of London and Bath in the early Sixties. Shot luminously in black and white CinemaScope the film incorporates archive footage that feels surprisingly effective with views of Battersea Power Station and London Bridge. A brief radio clip from a soundalike PM Harold MacMillan adds to the fun.

Valmond Maurice Guest (1911-2006) was an English film director and screenwriter who started his career on the British stage and in early sound films. He wrote over 70 scripts many of which he also directed, developing a versatile talent for making quality genre fare on a limited budget (Hell is a City, Casino Royale, The Boys in Blue). But Guest was best known for his Hammer horror pictures The Quatermass Xperiment and Quatermass II, and Sci-Fis The Day the Earth Caught Fire and 80,000 Suspects which nowadays provide a fascinating snapshot of London and Bath in the early Sixties. Shot luminously in black and white CinemaScope the film incorporates archive footage that feels surprisingly effective with views of Battersea Power Station and London Bridge. A brief radio clip from a soundalike PM Harold MacMillan adds to the fun.

Dresden 1918, Robert Siodmak left his upper-middle class, orthodox Jewish home in this epicentre of European modern art, to join a theatre touring company. He was 18, and this was the first of many radical changes that would see him becoming a pioneer of film noir, and directing 56 feature films fraught with (anti)heroes who are morose, malevolent, violent and generally downbeat (spoilers).

Dresden 1918, Robert Siodmak left his upper-middle class, orthodox Jewish home in this epicentre of European modern art, to join a theatre touring company. He was 18, and this was the first of many radical changes that would see him becoming a pioneer of film noir, and directing 56 feature films fraught with (anti)heroes who are morose, malevolent, violent and generally downbeat (spoilers).

Elliptical in nature, in the same way as

Elliptical in nature, in the same way as

The Flavour of Green Tea Over Rice tells the story of a marriage slowly imploding as Japan shifts into the modern world from its pre war traditions.

The Flavour of Green Tea Over Rice tells the story of a marriage slowly imploding as Japan shifts into the modern world from its pre war traditions. The 73rd Cannes Film Festival is not the only celebration to be postponed by the 2020 pandemic that has derailed the film calendar sending some editions online.

The 73rd Cannes Film Festival is not the only celebration to be postponed by the 2020 pandemic that has derailed the film calendar sending some editions online.  Dirty weekends don’t come any dirtier than the one in this ferocious indie revenge thriller that has ravishing locations, a twisty storyline, and a female lead who is not just a pretty face.

Dirty weekends don’t come any dirtier than the one in this ferocious indie revenge thriller that has ravishing locations, a twisty storyline, and a female lead who is not just a pretty face.

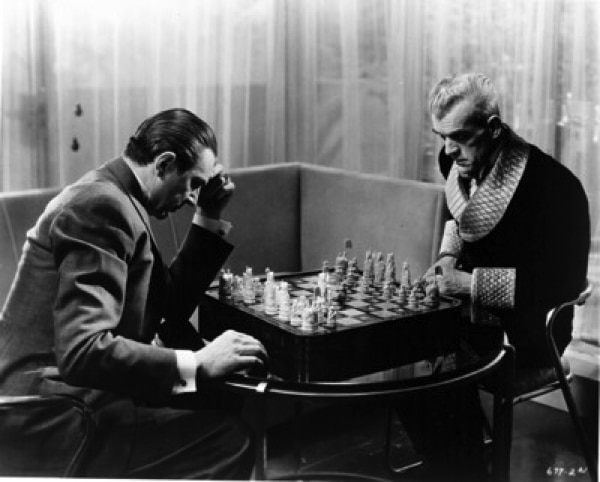

Dir.: Fritz Lang; Cast: Peter van Eyck, Dawn Addams, Gert Fröbe, Werner Peters, Wolfgang Preiss, Lupo Prezzo, Reinhard Kolldehoff; Germany/Italy/France 1960, 103 min.

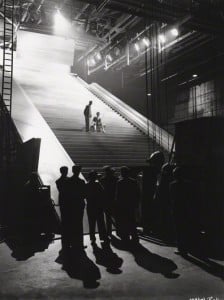

Dir.: Fritz Lang; Cast: Peter van Eyck, Dawn Addams, Gert Fröbe, Werner Peters, Wolfgang Preiss, Lupo Prezzo, Reinhard Kolldehoff; Germany/Italy/France 1960, 103 min. Films don’t always end up the way their makers originally envisaged at their outset, and the maiden production of Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger’s Archers Films would have turned out completely differently had Laurence Olivier been freed from the Fleet Air Arm to make it; since it is now impossible to imagine without third-billed Roger Livesey and his distinctive voice in the title role (in which at the age of 36 he convincingly ages forty years). The makers’ relative inexperience shows in the fact that they ended up with a initial cut over two and a half hours long; but fortunately J.Arthur Rank liked the film so much he let it hit cinemas as it was. Indeed, it was Pressburger’s favourite of the Rank outings, and would go on to influence the work of future filmmakers such as Scorsese in his The Age of Innocence and Tarantino who copied the device of beginning and ending a film be rerunning the same scene from the point of view of different characters.

Films don’t always end up the way their makers originally envisaged at their outset, and the maiden production of Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger’s Archers Films would have turned out completely differently had Laurence Olivier been freed from the Fleet Air Arm to make it; since it is now impossible to imagine without third-billed Roger Livesey and his distinctive voice in the title role (in which at the age of 36 he convincingly ages forty years). The makers’ relative inexperience shows in the fact that they ended up with a initial cut over two and a half hours long; but fortunately J.Arthur Rank liked the film so much he let it hit cinemas as it was. Indeed, it was Pressburger’s favourite of the Rank outings, and would go on to influence the work of future filmmakers such as Scorsese in his The Age of Innocence and Tarantino who copied the device of beginning and ending a film be rerunning the same scene from the point of view of different characters.

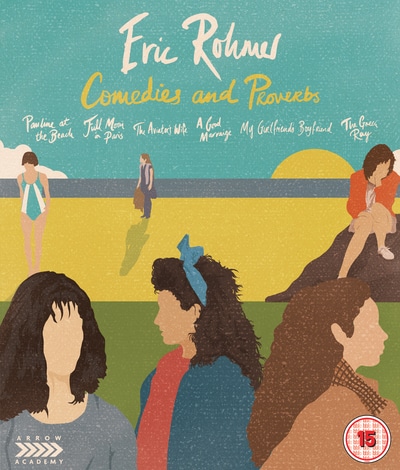

The Comedies and Proverbs series brings together six of Éric Rohmer’s best; the first entry in the series,

The Comedies and Proverbs series brings together six of Éric Rohmer’s best; the first entry in the series,

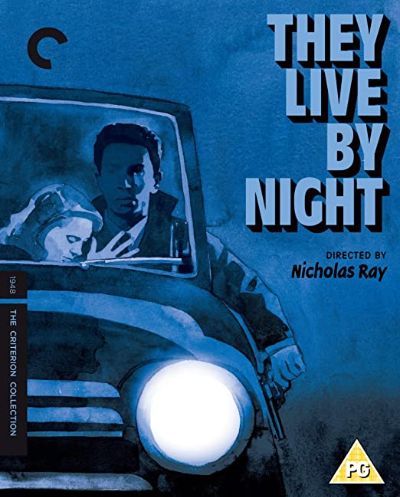

Legendary director Nicholas Ray began his career with this lyrical film noir, the first in a series of existential genre films overflowing with sympathy for America’s outcasts and underdogs. When the wide-eyed fugitive Bowie (Farley Granger), having broken out of prison with some bank robbers, meets the innocent Keechie (Cathy O’Donnell), each recognizes something in the other that no one else ever has.

Legendary director Nicholas Ray began his career with this lyrical film noir, the first in a series of existential genre films overflowing with sympathy for America’s outcasts and underdogs. When the wide-eyed fugitive Bowie (Farley Granger), having broken out of prison with some bank robbers, meets the innocent Keechie (Cathy O’Donnell), each recognizes something in the other that no one else ever has. Concise and pithy, this colourful film is narrated on camera by Samuel Aghoyan, the Superior of the Armenian Church, who takes us through a potted history of his own arrival as a child in the Holy City, and gives a sardonic take on the internecine tiffs that add spice to the daily life of this legendary ecclesiastical HQ sitting proudly in the Christian Quarter of the Old City of Jerusalem.

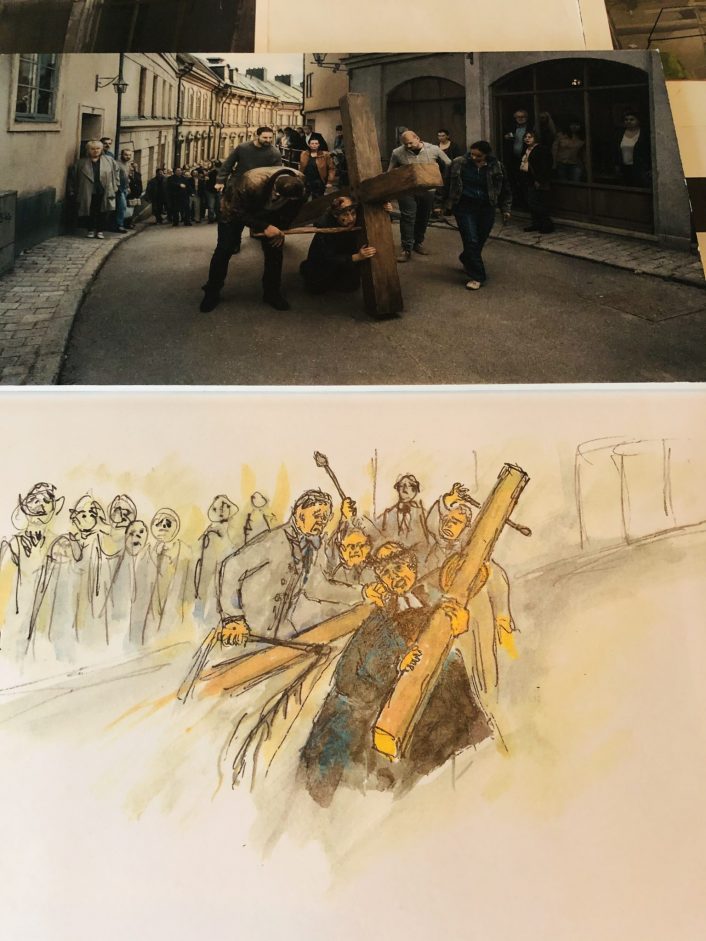

Concise and pithy, this colourful film is narrated on camera by Samuel Aghoyan, the Superior of the Armenian Church, who takes us through a potted history of his own arrival as a child in the Holy City, and gives a sardonic take on the internecine tiffs that add spice to the daily life of this legendary ecclesiastical HQ sitting proudly in the Christian Quarter of the Old City of Jerusalem. According to traditions, dating back to at least the fourth century, the building houses the two holiest sites in Christianity: the site where Jesus was crucified, at a place known as Calvary or Golgotha, and Jesus’s empty tomb, where he was buried and resurrected. The tomb is enclosed by a 19th-century shrine called the Aedicula. According to the history books, Jerusalem has had a chequered and controversial religious past. But eventually 260 years ago, the English were back in town and set up ‘The Status Quo’, an understanding between religious communities that must be respected across the board.

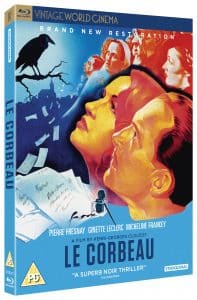

According to traditions, dating back to at least the fourth century, the building houses the two holiest sites in Christianity: the site where Jesus was crucified, at a place known as Calvary or Golgotha, and Jesus’s empty tomb, where he was buried and resurrected. The tomb is enclosed by a 19th-century shrine called the Aedicula. According to the history books, Jerusalem has had a chequered and controversial religious past. But eventually 260 years ago, the English were back in town and set up ‘The Status Quo’, an understanding between religious communities that must be respected across the board. Le Corbeau (1942)

Le Corbeau (1942) Upon its release in 1943, Le Corbeau was condemned by the political left and right and the church, and Clouzot was banned from filmmaking for two years.

Upon its release in 1943, Le Corbeau was condemned by the political left and right and the church, and Clouzot was banned from filmmaking for two years. Woman in Chains (1968)

Woman in Chains (1968)

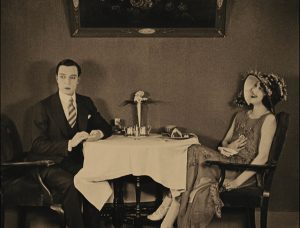

The Navigator (1924, dir. Buster Keaton & Donald Crisp) – Wealthy Rollo Treadway (Keaton) suddenly decides to propose to his neighbour across the street, Betsy O’Brien (Kathryn McGuire), and sends his servant to book passage for a honeymoon sea cruise to Honolulu. When Betsy rejects his sudden offer however, he decides to go on the trip anyway, boarding without delay that night. Because the pier number is partially covered, he ends up on the wrong ship, the Navigator, which Betsy’s rich father has just sold to a small country at war. Keaton was unhappy with the audience response to Sherlock Jr., and endeavoured to make a follow-up that was both exciting and successful. The result was the biggest hit of Keaton’s career and his personal favourite.

The Navigator (1924, dir. Buster Keaton & Donald Crisp) – Wealthy Rollo Treadway (Keaton) suddenly decides to propose to his neighbour across the street, Betsy O’Brien (Kathryn McGuire), and sends his servant to book passage for a honeymoon sea cruise to Honolulu. When Betsy rejects his sudden offer however, he decides to go on the trip anyway, boarding without delay that night. Because the pier number is partially covered, he ends up on the wrong ship, the Navigator, which Betsy’s rich father has just sold to a small country at war. Keaton was unhappy with the audience response to Sherlock Jr., and endeavoured to make a follow-up that was both exciting and successful. The result was the biggest hit of Keaton’s career and his personal favourite.

Merce was also passionate about working with artists from other disciplines including composer John Cage, Cunningham’s longterm partner; the painter Robert Rauschenberg; and Andy Warhol whose collaboration is particularly striking in Merce’s 1968 Sci-fi themed dance work Rainforest which featured Warhol’s metallic helium-filled silver balloons (the Silver Clouds) that float around the dancers like something from outer space.

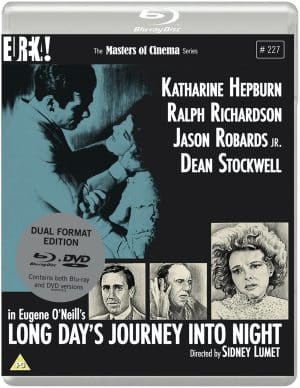

Merce was also passionate about working with artists from other disciplines including composer John Cage, Cunningham’s longterm partner; the painter Robert Rauschenberg; and Andy Warhol whose collaboration is particularly striking in Merce’s 1968 Sci-fi themed dance work Rainforest which featured Warhol’s metallic helium-filled silver balloons (the Silver Clouds) that float around the dancers like something from outer space. Nobel literate Eugene O’Neill (1888-1953) wrote Long Day’s Journey into Night in 1941/42. He stipulated that the highly autobiographical play should not be staged until 25 years after his death. But his widow Charlotta Monterey was so impressed by Lumet’s stage production of late husband’s play The Iceman Cometh she gave him the film rights despite higher bids from other directors. Trust the Swedes to get their paws on the gloomy Bergman-esque play), it premiered in in Stockholm in 1956, nine months before the first US staging in Boston and New York,

Nobel literate Eugene O’Neill (1888-1953) wrote Long Day’s Journey into Night in 1941/42. He stipulated that the highly autobiographical play should not be staged until 25 years after his death. But his widow Charlotta Monterey was so impressed by Lumet’s stage production of late husband’s play The Iceman Cometh she gave him the film rights despite higher bids from other directors. Trust the Swedes to get their paws on the gloomy Bergman-esque play), it premiered in in Stockholm in 1956, nine months before the first US staging in Boston and New York, L

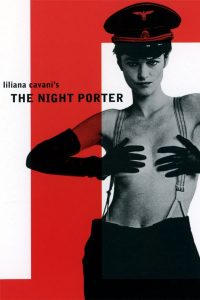

L THE NIGHT PORTER (Il portiere di notte) Dir: Liliana Cavani | Cast: Dirk Bogarde, Charlotte Rampling, Philippe Leroy | 118 mins

THE NIGHT PORTER (Il portiere di notte) Dir: Liliana Cavani | Cast: Dirk Bogarde, Charlotte Rampling, Philippe Leroy | 118 mins

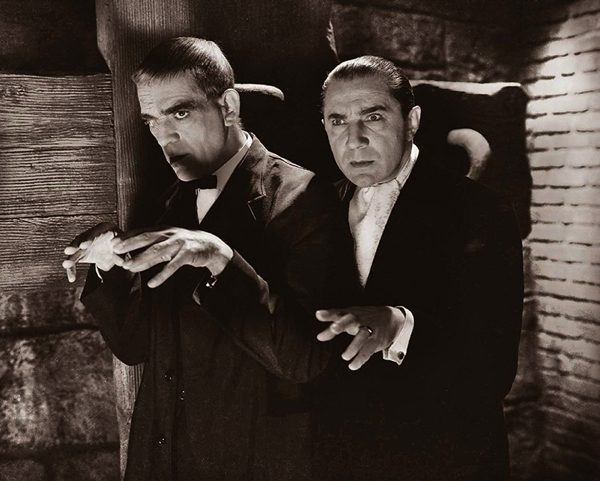

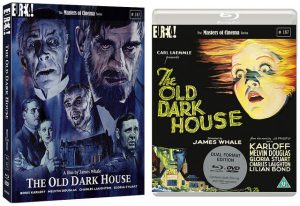

Dir: James Whale | Wri: Benn Levy/J B Priestley | Cast: Boris Karloff| Charles Laughton | Eva Moore | Gloria Stuart | Melvyn Douglas| Raymond Massey | Horror / Comedy |US 75′

Dir: James Whale | Wri: Benn Levy/J B Priestley | Cast: Boris Karloff| Charles Laughton | Eva Moore | Gloria Stuart | Melvyn Douglas| Raymond Massey | Horror / Comedy |US 75′

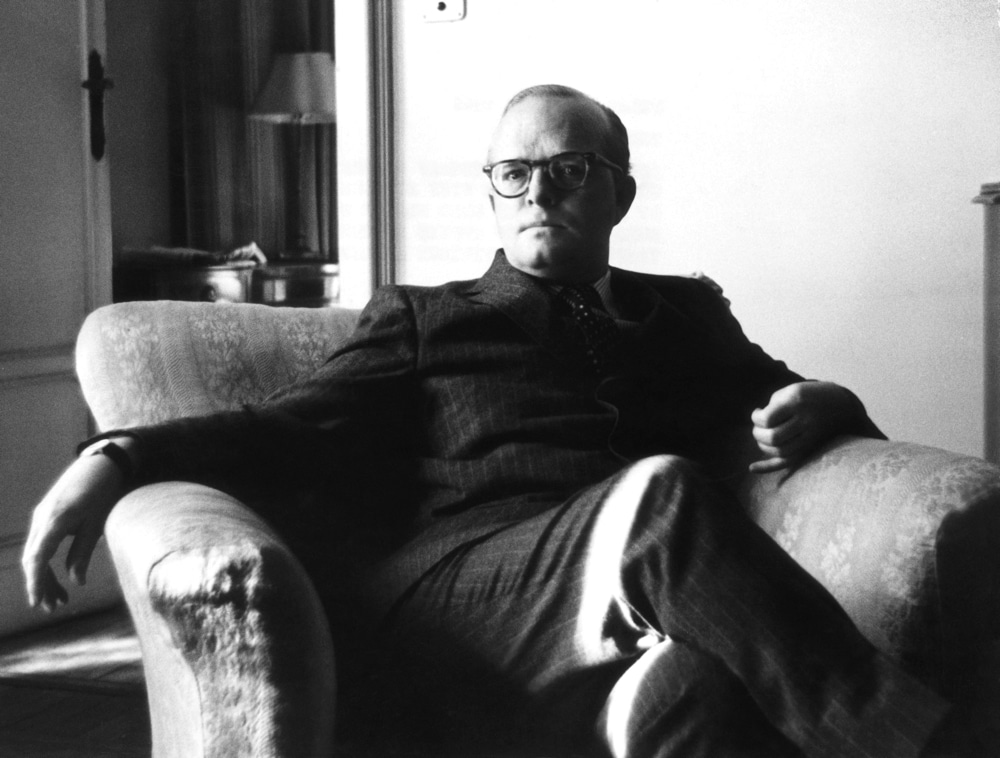

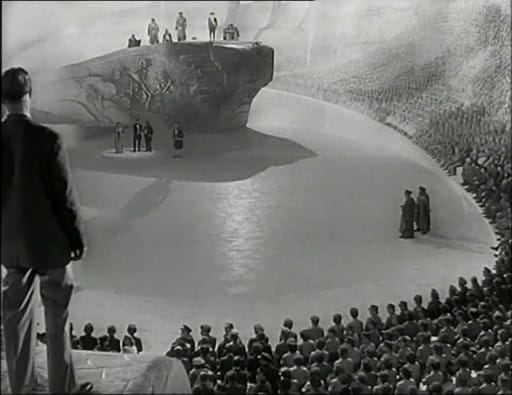

Documentary wise: Ebs Burnough’s The Capote Tapes takes us back through the archives to revisit the iconic American novelist, while Nanni Moretti’s Santiago, Italia (left) explores the Italian role in rescuing exiles out of Chile after Pinochet’s Coup d’Etat.

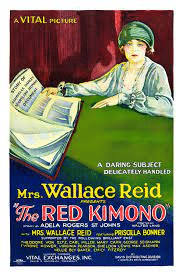

Documentary wise: Ebs Burnough’s The Capote Tapes takes us back through the archives to revisit the iconic American novelist, while Nanni Moretti’s Santiago, Italia (left) explores the Italian role in rescuing exiles out of Chile after Pinochet’s Coup d’Etat.  Women filmmakers will be also championed in Mark Cousins’ 2018 epic homage to the history of female talent: Women Make Film:

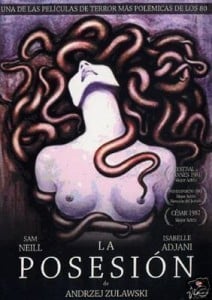

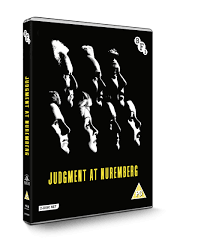

Women filmmakers will be also championed in Mark Cousins’ 2018 epic homage to the history of female talent: Women Make Film: Director Stanley Kramer (1913-2001) was always ready to bring controversial stories to the screen, Guess Who is Coming to Dinner being one of them. When he directed Aby Mann’s adaption of his own story in 1961, Judgement at Nuremberg was very much a slap in the face for Cold War warriors, who had forgiven (West) Germans the Holocaust, just to have old Nazis to fight against Bolshevism.

Director Stanley Kramer (1913-2001) was always ready to bring controversial stories to the screen, Guess Who is Coming to Dinner being one of them. When he directed Aby Mann’s adaption of his own story in 1961, Judgement at Nuremberg was very much a slap in the face for Cold War warriors, who had forgiven (West) Germans the Holocaust, just to have old Nazis to fight against Bolshevism.