In Park City Utah, ROBERT REDFORD and his programmer John Cooper have set the indie film agenda for 2020 with an array of provocative new titles in a festival that runs from 23 January until 2 February. This year’s selection includes the latest US drama from Josephine Decker (Thou Wast Mild and Lovely); and new documentaries about Chechnya, Bruce Lee and Woodstock competing in the US Dramatic section. Branden Cronenberg will be showing his latest film, Possessor starring Andrea Riseborough; who also appears in the Egyptian drama Luxor. Noemie Merlant is fresh from Portrait of a Woman on Fire, in Zoe Wittock’s Jumbo.

UK director Oscar Raby brings A Machine for Viewing, a unique three-episode hybrid of real-time VR experience, live performance and video essay in which three moving-image makers explore how we now watch films by putting various ‘machines for viewing,’ including cinema and virtual reality, face to face.

EXHIBITIONS

All Kinds of Limbo / United Kingdom (Lead Artists: Toby Coffey, Raffy Bushman, Nubiya Brandon) — The National Theatre of Great Britain’s communal musical journey reflecting the influence of West Indian culture on the UK’s music scene across the genres of reggae, grime, classical, and calypso. Immersive technologies, the ceremony of live performance and the craft of theatrical staging bring audiences into a VR performance space. Cast: Nubiya Brandon.

U.S. DRAMATIC COMPETITION

47% of the directors in this year’s U.S. Dramatic Competition are women; 52% are people of color; 5% are LGBTQ+.

The 40-Year-Old Version / U.S.A. Director and screenwriter: Radha Blank

A down-on-her-luck New York playwright decides to reinvent herself and salvage her artistic voice the only way she knows how: by becoming a rapper at age 40. Cast: Radha Blank, Peter Kim, Oswin Benjamin, Reed Birney, World Premiere

BLAST BEAT / U.S.A. Director: Esteban Arango

After their family emigrates from Colombia during the summer of ‘99, a metalhead science prodigy and his deviant younger brother do their best to adapt to new lives in America. Cast: Moises Arias, Mateo Arias, Daniel Dae Kim, Kali Uchis, Diane Guerrero, Wilmer Valderrama. World Premiere

Charm City Kings / U.S.A. (Director: Angel Manuel Soto

Mouse desperately wants to join The Midnight Clique, the infamous Baltimore dirt bike riders who rule the summertime streets. When Midnight’s leader, Blax, takes 14-year-old Mouse under his wing, Mouse soon finds himself torn between the straight-and-narrow and a road filled with fast money and violence.

Cast: Jahi Di’Allo Winston, Meek Mill, Will Catlett, Teyonah Parris, Donielle Tremaine World Premiere

Dinner in America / U.S.A. (Dir/writer: Adam Rehmeier

An on-the-lam punk rocker and a young woman obsessed with his band go on an unexpected and epic journey together through the decaying suburbs of the American Midwest.. Cast: Kyle Gallner, Emily Skeggs, Pat Healy, Griffin Gluck, Lea Thompson, Mary Lynn Rajskub. World Premiere

The Evening Hour / U.S.A. Dir: Braden King

Cole Freeman maintains an uneasy equilibrium in his rural Appalachian town, looking after the old and infirm while selling their excess painkillers to local addicts. But when an old friend returns with plans that upend the fragile balance and identity he’s so painstakingly crafted, Cole is forced to take action. Cast: Philip Ettinger, Stacy Martin, Cosmo Jarvis, Michael Trotter, Kerry Bishé, Lili Taylor. World Premiere

Farewell Amor / U.S.A. (Dir/writer: Ekwa Msangi

Reunited after a 17 year separation, Walter, an Angolan immigrant, is joined in the U.S. by his wife and teenage daughter. Now absolute strangers sharing a one-bedroom apartment, they discover a shared love of dance that may help overcome the emotional distance between them. Cast: Ntare Guma Mbaho Mwine, Zainab Jah, Jayme Lawson, Joie Lee, Marcus Scribner, Nana Mensah. World Premiere

Minari / U.S.A. (Dir/writer: Lee Isaac Chung

David, a 7-year-old Korean-American boy, gets his life turned upside down when his father decides to move their family to rural Arkansas and start a farm in the mid-1980s, in this charming and unexpected take on the American Dream. Cast: Steven Yeun, Han Yeri, Youn Yuh Jung, Will Patton, Alan Kim, Noel Kate Cho. World Premiere

Miss Juneteenth / U.S.A. (Dir/Writer: Channing Godfrey Peoples

Turquoise, a former beauty queen turned hardworking single mother, prepares her rebellious teenage daughter for the “Miss Juneteenth” pageant, hoping to keep her from repeating the same mistakes in life that she did. Cast: Nicole Beharie, Kendrick Sampson, Alexis Chikaeze, Lori Hayes, Marcus Maudlin. World Premiere

Never Rarely Sometimes Always / U.S.A. (Dir/Wri: Eliza Hittman

An intimate portrayal of two teenage girls in rural Pennsylvania. Faced with an unintended pregnancy and a lack of local support, Autumn and her cousin Skylar embark on a brave, fraught journey across state lines to New York City. Cast: Sidney Flanigan, Talia Ryder, Théodore Pellerin, Ryan Eggold, Sharon Van Etten. World Premiere

Nine Days / U.S.A. (Dir/Writer: Edson Oda,

In a house distant from the reality we know, a reclusive man interviews prospective candidates—personifications of human souls—for the privilege that he once had: to be born. Cast: Winston Duke, Zazie Beetz, Benedict Wong, Bill Skarsgård, Tony Hale, David Rysdahl. World Premiere.

Palm Springs / U.S.A. Dir: Max Barbakow

When carefree Nyles and reluctant maid of honor Sarah have a chance encounter at a Palm Springs wedding, things get complicated the next morning when they find themselves unable to escape the venue, themselves, or each other. Cast: Andy Samberg, Cristin Milioti, J.K. Simmons, Meredith Hagner, Camila Mendes, Peter Gallagher. World Premiere

Save Yourselves! / U.S.A. Dir/Wri: Alex Huston Fischer, Eleanor Wilson

A young Brooklyn couple head upstate to disconnect from their phones and reconnect with themselves. Cut off from their devices, they miss the news that the planet is under attack. Cast: Sunita Mani, John Reynolds, Ben Sinclair, Johanna Day, John Early, Gary Richardson. World Premiere

Shirley / U.S.A. Dir: Josephine Decker

A young couple moves in with the famed author, Shirley Jackson, and her Bennington College professor husband, Stanley Hyman, in the hope of starting a new life but instead find themselves fodder for a psycho-drama that inspires Shirley’s next novel. Cast: Elisabeth Moss, Michael Stuhlbarg, Odessa Young, Logan Lerman. World Premiere

Sylvie’s Love / U.S.A. (Dir/Wri: Eugene Ashe

Years after their summer romance comes to an end, an aspiring television producer and a talented musician cross paths, only to find their feelings for each other never changed. With their careers taking them in different directions, they must choose what matters most. Cast: Tessa Thompson, Nnamdi Asomugha, Eva Longoria, Aja Naomi King, Wendi Mclendon-Covey, Jemima Kirke. World Premiere

Wander Darkly / U.S.A. (Dir/Wri: Tara Miele

New parents Adrienne and Matteo are forced to reckon with trauma amidst their troubled relationship. They must revisit the memories of their past and unravel haunting truths in order to face their uncertain future. Cast: Sienna Miller, Diego Luna, Beth Grant, Aimee Carrero, Tory Kittles, Vanessa Bayer. World Premiere

Zola / U.S.A. (Dir/Wri: Janicza Bravo, Jeremy O. Harris

@zolarmoon tweets “wanna hear a story about why me & this bitch here fell out???????? It’s kind of long but full of suspense.” Two girls bond over their “hoeism” and become fast friends. What’s supposed to be a trip from Detroit to Florida turns into a weekend from hell. Cast: Taylour Paige, Riley Keough, Nicholas Braun, Colman Domingo. World Premiere

U.S. DOCUMENTARY COMPETITION

Sixteen world-premiere American documentaries that illuminate the ideas, people and events that shape the present day. Films that have premiered in this category in recent years include APOLLO 11, Knock Down The House, One Child Nation, American Factory, Three Identical Strangers and On Her Shoulders. 45% of the directors in this year’s U.S. Documentary Competition are women; 23% are people of color; 23% are LGBTQ+.

A Thousand Cuts / U.S.A., Philippines Dir/Wri:Ramona S Diaz

Nowhere is the worldwide erosion of democracy, fueled by social media disinformation campaigns, more starkly evident than in the authoritarian regime of Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte. Journalist Maria Ressa places the tools of the free press—and her freedom—on the line in defense of truth and democracy. World Premiere

Be Water / U.S.A., UK Director: Bao Nguyen

In 1971, after being rejected by Hollywood, Bruce Lee returned to his parents’ homeland of Hong Kong to complete four iconic films. Charting his struggles between two worlds, this portrait explores questions of identity and representation through the use of rare archival, interviews with loved ones and Bruce’s own writings. World Premiere

Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets / U.S.A. Dir: Bill Ross, Turner Ross

In the shadows of the bright lights of Las Vegas, it’s last call for a beloved dive bar known as the Roaring 20s. A document of real people, in an unreal situation, facing an uncertain future: America at the end of 2016. World Premiere

Boys State / U.S.A. Dirs Jesse Moss, Amanda McBaine,

In an unusual experiment, a thousand 17-year-old boys from Texas join together to build a representative government from the ground up. World Premiere

Code for Bias / US/UK/China Dir/Wri Shalini Kantayya

Exploring the fallout of MIT Media Lab researcher Joy Buolamwini’s startling discovery that facial recognition does not see dark-skinned faces accurately, and her journey to push for the first-ever legislation in the U.S. to govern against bias in the algorithms that impact us all. World Premiere

The Cost of Silence / US Dir: Mark Manning

An industry insider exposes the devastating consequences of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill and uncovers systemic corruption between government and industry to silence the victims of a growing public health disaster. Stakes could not be higher as the Trump administration races to open the entire U.S. coastline to offshore drilling. World Premiere

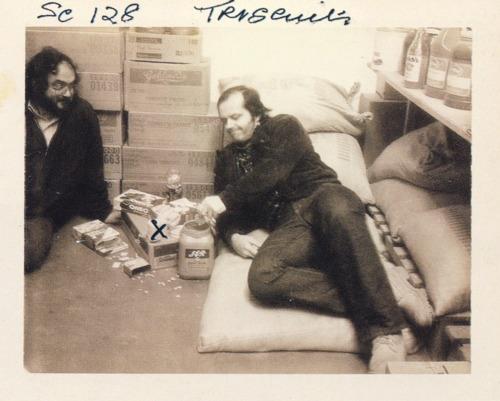

Crip Camp / U.S.A. (Dir: Nicole Newnham, Jim LeBrecht,

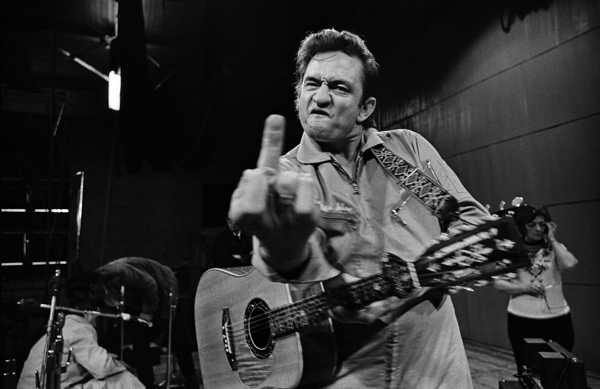

Down the road from Woodstock in the early 1970s, a revolution blossomed in a ramshackle summer camp for disabled teenagers, transforming their young lives and igniting a landmark movement. World Premiere. DAY ONE

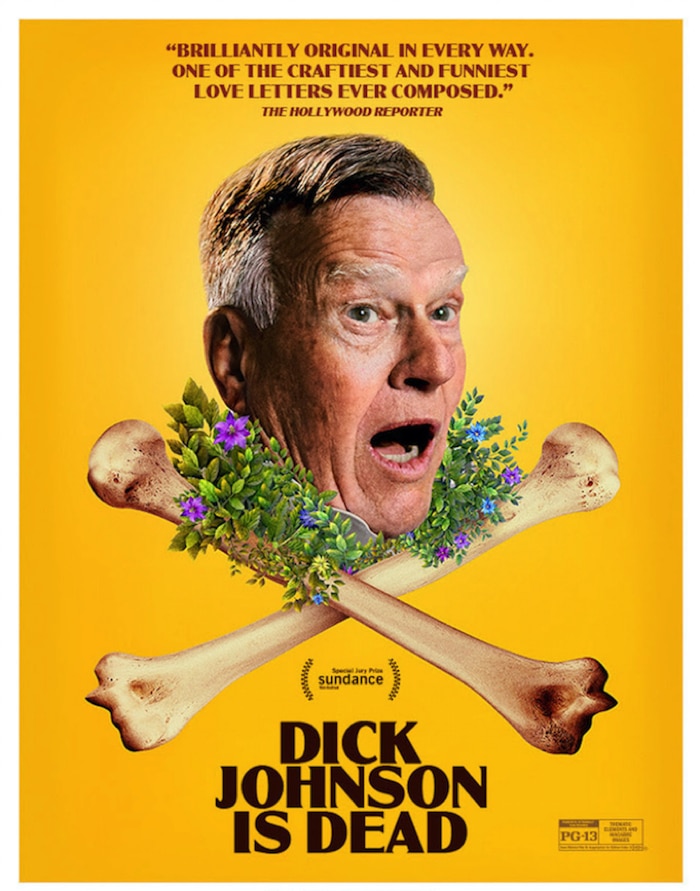

Dick Johnson Is Dead / US. Dir: Kirsten Johnson

With this inventive portrait, a cameraperson seeks a way to keep her 86-year-old father alive forever. Utilizing moviemaking magic and her family’s dark humor, she celebrates Dr. Dick Johnson’s last years by staging fantasies of death and beyond. Together, dad and daughter confront the great inevitability awaiting us all. World Premiere

Feels Good Man / US. Dir: Arthur Jones

When indie comic character Pepe the Frog becomes an unwitting icon of hate, his creator, artist Matt Furie, fights to bring Pepe back from the darkness and navigate America’s cultural divide. World Premiere

The Fight / US. | Dirs: Elyse Steinberg, Josh Kriegman, Eli Despres

Inside the ACLU, a team of scrappy lawyers battle Trump’s historic assault on civil liberties. World Premiere

Mucho Mucho Amor / US. Dirs: Cristina Costantini, Kareem Tabsch

Once the world’s most famous astrologer, Walter Mercado seeks to resurrect a forgotten legacy. Raised in the sugar cane fields of Puerto Rico, Walter grew up to become a gender non-conforming, cape-wearing psychic whose televised horoscopes reached 120 million viewers a day for decades before he mysteriously disappeared. World Premiere

Spaceship Earth / U.S.A. Director: Matt Wolf

In 1991 a group of countercultural visionaries built an enormous replica of earth’s ecosystem called Biosphere 2. When eight “biospherians” lived sealed inside, they faced ecological calamities and cult accusations. Their epic adventure is a cautionary tale but also a testament to the power of small groups reimagining the world. World Premiere

Time / U.S.A. (Director: Garrett Bradley

Fox Rich, indomitable matriarch and modern-day abolitionist, strives to keep her family together while fighting for the release of her incarcerated husband. An intimate, epic, and unconventional love story, filmed over two decades. World Premiere

Us Kids / U.S.A. (Dir: Kim A. Snyder

Determined to turn unfathomable tragedy into action, the teenage survivors of Parkland, Florida catalyze a powerful, unprecedented youth movement that spreads with lightning speed across the country, as a generation of mobilized youth take back democracy in this powerful coming-of-age story. World Premiere

Welcome to Chechnya / U.S.A. (Dir: David France

This searing investigative work shadows a group of activists risking unimaginable peril to confront the ongoing anti-LGBTQ pogrom raging in the repressive and closed Russian republic. Unfettered access and a remarkable approach to protecting anonymity exposes this under-reported atrocity–and an extraordinary group of people confronting evil. World Premiere

Whirlybird / U.S.A. Dir: Matt Yoka

Soaring above the chaotic spectacle of ‘80s and ‘90s Los Angeles, a young couple revolutionized breaking news with their brazen helicopter reporting. Culled from this news duo’s sprawling video archive is a poignant L.A. story of a family in turbulence hovering over a city unhinged. World Premiere

WORLD CINEMA DRAMATIC COMPETITION

Twelve films from emerging filmmaking talents around the world offer fresh perspectives and inventive styles. Films that have premiered in this category in recent years include The Souvenir, The Guilty, Monos, Yardie, The Nile Hilton Incident and Second Mother.

Charter / Sweden (Dir/Wri: Amanda Kernell |

After a recent and difficult divorce, Alice hasn’t seen her children in two months as she awaits a custody verdict. When her son calls her in the middle of the night, Alice takes action, abducting the children on an illicit charter trip to the Canary Islands. Cast: Ane Dahl Torp, Troy Lundkvist, Tintin Poggats Sarri, Sverrir Gudnason, Eva Melander, Siw Erixon. World Premiere

Cuties / France (Dir/Wri: Maïmouna Doucouré, Producer: Zangro)

Amy, 11 years old, meets a group of dancers called “Cuties.” Fascinated, she initiates herself to a sensual dance, hoping to join their band and escape family dysfunction… Cast: Fathia Youssouf, Médina El Aidi-Azouni, Esther Gohourou, Ilanah Cami-Goursolas, Myriam Hamma, Maïmouna Gueye. World Premiere. DAY ONE

Exil / Germany, Belgium, Kosovo (Dir/Wri: Visar Morina

A chemical engineer feeling discriminated against and bullied at work plunges into an identity crisis. Cast: Mišel Matičević, Sandra Hüller. World Premiere

High Tide / Argentina (Dir/Wri: Verónica Chen,

Laura is spending a few days at her beach house to supervise the construction of a barbecue shed. One afternoon, she seduces the chief builder, who never returns. Over the following days, the builders continually invade her home – until Laura grows ferocious. Cast: Gloria Carrá, Jorge Sesán, Cristian Salguero, Mariana Chaud, Camila Fabbri, Héctor Bordoni. World Premiere

Jumbo / France, Luxembourg, Belgium (Dir/Wri: Zoé Wittock,

Jeanne, a shy young woman, works in an amusement park. Fascinated with carousels, she still lives at home with her mother. That’s when Jeanne meets Jumbo, the park’s new flagship attraction… Cast: Noémie Merlant, Emmanuelle Bercot, Sam Louwyck. World Premiere

Luxor / Egypt, United Kingdom Dir/Wri Zeina Durra,

When British aid worker Hana returns to the ancient city of Luxor, she comes across Sultan, a talented archeologist and former lover. As she wanders, haunted by the familiar place, she struggles to reconcile the choices of the past with the uncertainty of the present. Cast: Andrea Riseborough, Karim Saleh, Michael Landes, Sherine Reda, Salima Ikram, Shahira Fahmy. World Premiere

Possessor / Canada, United Kingdom Dir/Wri: Brandon Cronenberg,

Vos is a corporate agent who uses brain-implant technology to inhabit other people’s bodies, driving them to commit assassinations for the benefit of the company. When something goes wrong on a routine job, she finds herself trapped inside a man whose identity threatens to obliterate her own. Cast: Andrea Riseborough, Christopher Abbott, Rossif Sutherland, Tuppence Middleton, Sean Bean, Jennifer Jason Leigh. World Premiere

Identifying Features (Sin Señas Particulares) / Mexico, Spain (Director: Fernanda Valadez,

Magdalena makes a journey to find her son, gone missing on his way to the Mexican border with the US. Her odyssey takes her to meet Miguel, a man recently deported from the U.S. They travel together, Magdalena looking for her son, and Miguel hoping to see his mother again. Cast: Mercedes Hernández, David Illescas, Juan Jesús Varela, Ana Laura Rodríguez, Laura Elena Ibarra, Xicoténcatl Ulloa. World Premiere

Summer White (Blanco de Verano) / Mexico (Dir/Wri: Rodrigo Ruiz Patterson,

Rodrigo is a solitary teenager, a king in the private world he shares with his mother. Things change when she takes her new boyfriend home to live. He must decide if he fights for his throne and crushes the happiness of the person he loves the most. Cast: Adrián Rossi, Sophie Alexander-Katz, Fabián Corres. World Premiere

Surge / United Kingdom (Director: Aneil Karia

A man goes on a bold and reckless journey of self-liberation through London. After he robs a bank he releases a wilder version of himself, ultimately experiencing what it feels like to be alive. Cast: Ben Whishaw, Ellie Haddington, Ian Gelder, Jasmine Jobson. World Premiere

This Is Not A Burial, It’s A Resurrection / Lesotho, South Africa, Italy (Dir/Wri Lemohang Jeremiah Mosese

When her village is threatened with forced resettlement due to reservoir construction, an 80-year-old widow finds a new will to live and ignites the spirit of resilience within her community. In the final dramatic moments of her life, Mantoa’s legend is forged and made eternal. Cast: Mary Twala Mhlongo, Jerry Mofokeng Wa Makheta, Makhoala Ndebele, Tseko Monaheng, Siphiwe Nzima. International Premiere

Yalda, a Night for Forgiveness / Iran, France, Germany, Switzerland, Luxembourg (Dir/Wri: Massoud Bakhshi,

Maryam accidentally killed her husband Nasser and is sentenced to death. The only person who can save her is Mona, Nasser’s daughter. All Mona has to do is appear on a TV show and forgive Maryam. But forgiveness proves difficult when they are forced to relive the past. Cast: Sadaf Asgari, Behnaz Jafari, Babak Karimi, Fereshteh Sadr Orafaee, Forough Ghajebeglou, Fereshteh Hosseini. International Premiere

WORLD CINEMA DOCUMENTARY COMPETITION

Twelve documentaries by some of the most courageous and extraordinary international filmmakers working today. Films that have premiered in this category in recent years include Honeyland, Sea of Shadows, Shirkers, This is Home, Last Men in Aleppo and Hooligan Sparrow.

Acasa, My Home / Romania, Germany, Finland (Director: Radu Ciorniciuc, Screenwriters: Lina Vdovii, Radu Ciorniciuc, Producer: Monica Lazurean-Gorgan

In the wilderness of the Bucharest Delta, nine children and their parents lived in perfect harmony with nature for 20 years–until they are chased out and forced to adapt to life in the big city. World Premiere

The Earth Is Blue as an Orange / Ukraine, Lithuania (Director: Iryna Tsilyk,

To cope with the daily trauma of living in a war zone, Anna and her children make a film together about their life among surreal surroundings. World Premiere

Epicentro / Austria, France, U.S.A. (Dir/writer: Hubert Sauper,

Cuba is well known as a so-called time capsule. The place where the New World was discovered has become both a romantic vision and a warning. With ongoing global cultural and financial upheavals, large parts of the world could face a similar kind of existence. World Premiere

Influence / South Africa, Canada (Directors and Screenwriters: Diana Neille, Richard Poplak,

Charting the recent advancements in weaponized communication by investigating the rise and fall of the world’s most notorious public relations and reputation management firm: the British multinational Bell Pottinger. World Premiere

Into the Deep / Denmark (Dir: Emma Sullivan

In 2016, a young Australian filmmaker began documenting amateur inventor Peter Madsen. One year in, Madsen brutally murdered Kim Wall aboard his homemade submarine. An unprecedented revelation of a killer and the journey his young helpers take as they reckon with their own complicity and prepare to testify. World Premiere

The Mole Agent / Chile, U.S.A., Germany, The Netherlands, Spain (Dir and screenwriter: Maite Alberdi

When a family becomes concerned about their mother’s well-being in a retirement home, private investigator Romulo hires Sergio, an 83 year-old man who becomes a new resident–and a mole inside the home, who struggles to balance his assignment with becoming increasingly involved in the lives of several residents. World Premiere

Once Upon A Time in Venezuela / Venezuela, United Kingdom, Brazil, Austria (DirWri: Anabel Rodríguez Ríos,

Once upon a time, the Venezuelan village of Congo Mirador was prosperous, alive with fisherman and poets. Now it is decaying and disintegrating–a small but prophetic reflection of Venezuela itself. World Premiere

The Painter and the Thief / Norway Director: Benjamin Ree

An artist befriends the drug addict and thief who stole her paintings. She becomes his closest ally when he is severely hurt in a car crash and needs full time care, even if her paintings are not found. But then the tables turn. World Premiere. DAY ONE

The Reason I Jump / United Kingdom Dir: Jerry Rothwell

Based on the book by Naoki Higashida this immersive film explores the experiences of nonspeaking autistic people around the world. World Premiere

Saudi Runaway / Switzerland (Dir/Wri: Susanne Regina Meures, Producer: Christian Frei) — Muna, a young, fearless woman from Saudi Arabia, is tired of being controlled by the state and patronised by her family. With an arranged marriage imminent, a life without rights and free will seems inevitable. Amjad decides to escape. An unprecedented view inside the world’s most repressive patriarchy. World Premiere

Softie / Kenya (Director and screenwriter: Sam Soko, Producers: Toni Kamau, Sam Soko) — Boniface Mwangi is daring and audacious, and recognized as Kenya’s most provocative photojournalist. But as a father of three young children, these qualities create tremendous turmoil between him and his wife Njeri. When he wants to run for political office, he is forced to choose: country or family? World Premiere

The Truffle Hunters / Italy, U.S.A., Greece (Dirs: Michael Dweck, Gregory Kershaw

In the secret forests of Northern Italy, a dwindling group of joyful old men and their faithful dogs search for the world’s most expensive ingredient, the white Alba truffle. Their stories form a real-life fairy tale that celebrates human passion in a fragile land that seems forgotten in time. World Premiere

SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL | 23 JANUARY – 2 FEBRUARY 2020

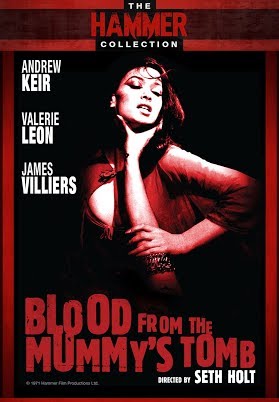

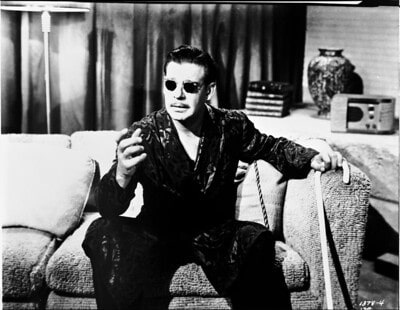

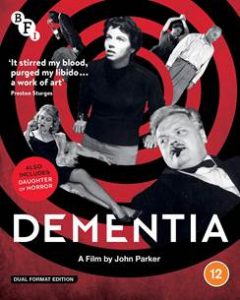

Atmospherically directed by Hungarian Peter Sasdy, and adapted for the screen by Anthony Hinds – stepping in due to budgetary constraints under the pseudonym of John Elder (he told his neighbours he was a hairdresser to avoid publicity throughout his entire career) this outing actually broadens the storyline into a damning social satire of Victorian repression and upper class ennui. The eclectic cast has Christopher Lee, Geoffrey Keen and Gwen Watford and sees three distinguished English gentlemen (Keen, Peter Sallis and John Carson) descend into Satanism, for want of anything better to do, accidentally killIng Dracula‘s sidekick Lord Courtly (Ralph Bates), in the process. As an act of revenge the Count vows they will die at the hands of their own children. But Lee actually bloodies the waters in the second half, swanning in glowering due to his lack of a domineering role in the proceedings.

Atmospherically directed by Hungarian Peter Sasdy, and adapted for the screen by Anthony Hinds – stepping in due to budgetary constraints under the pseudonym of John Elder (he told his neighbours he was a hairdresser to avoid publicity throughout his entire career) this outing actually broadens the storyline into a damning social satire of Victorian repression and upper class ennui. The eclectic cast has Christopher Lee, Geoffrey Keen and Gwen Watford and sees three distinguished English gentlemen (Keen, Peter Sallis and John Carson) descend into Satanism, for want of anything better to do, accidentally killIng Dracula‘s sidekick Lord Courtly (Ralph Bates), in the process. As an act of revenge the Count vows they will die at the hands of their own children. But Lee actually bloodies the waters in the second half, swanning in glowering due to his lack of a domineering role in the proceedings.

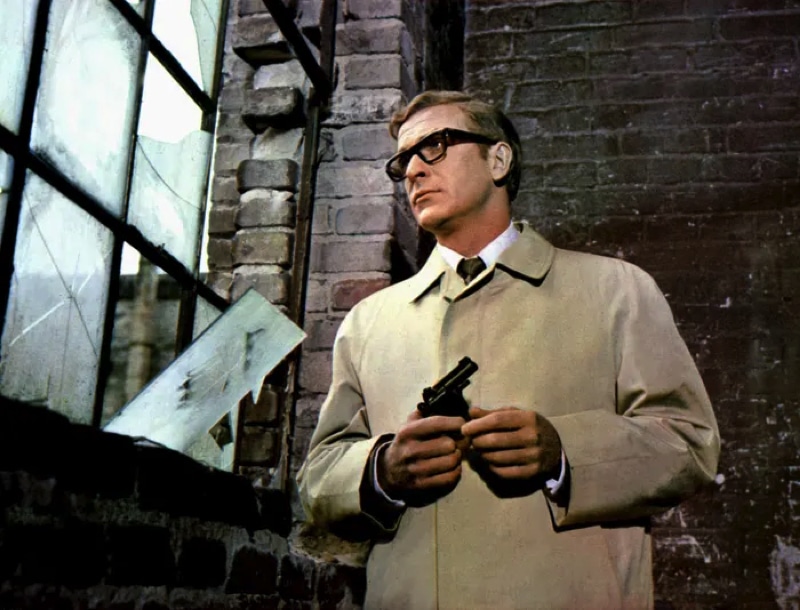

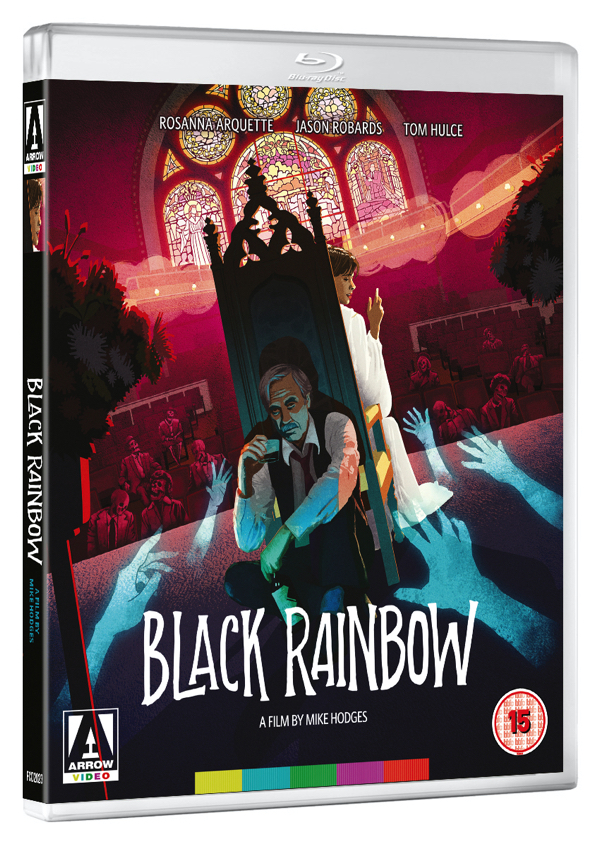

Rosanna Arquette shines as a clairvoyant on tour with her father (Jason Robards) in this supernatural curio from undervalued English director Mike Hodges.

Rosanna Arquette shines as a clairvoyant on tour with her father (Jason Robards) in this supernatural curio from undervalued English director Mike Hodges. Filtering the darkest, most dramatic period of modern Jewish history through the instinctive gaze of a dog was an ambitious idea for the best selling Israeli author Asher Kravitz. So Lynn Roth’s efforts to accommodate a young audience in her screen version are laudable but the upshot often cringeworthy.

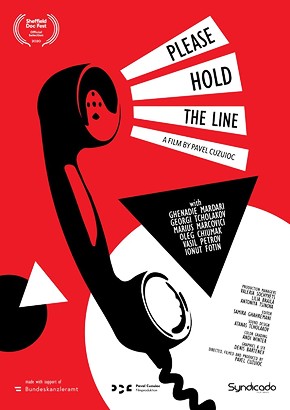

Filtering the darkest, most dramatic period of modern Jewish history through the instinctive gaze of a dog was an ambitious idea for the best selling Israeli author Asher Kravitz. So Lynn Roth’s efforts to accommodate a young audience in her screen version are laudable but the upshot often cringeworthy. The past and the present collide in this darkly amusing deep dive into the human side of the digital age. And each are as complex as the other according to Pavel Cuzuoic, whose third documentary works on two levels: As an abstract expressionist arthouse piece and a deadpan social and political satire. What emerges is a priceless look at a society in flux in Bulgaria, Romania, Moldova and Ukraine. The old fights with the new, refusing to give in.

The past and the present collide in this darkly amusing deep dive into the human side of the digital age. And each are as complex as the other according to Pavel Cuzuoic, whose third documentary works on two levels: As an abstract expressionist arthouse piece and a deadpan social and political satire. What emerges is a priceless look at a society in flux in Bulgaria, Romania, Moldova and Ukraine. The old fights with the new, refusing to give in.

Mangrove, Steve McQueen (UK), 2h04′

Mangrove, Steve McQueen (UK), 2h04′ Last Words, Jonathan Nossiter (USA)

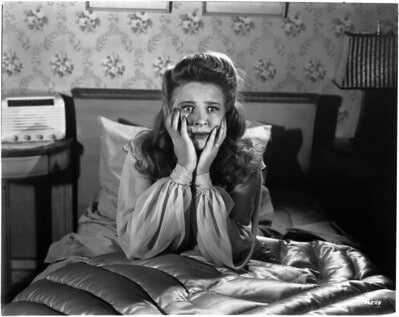

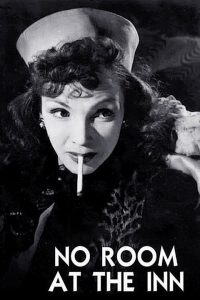

Last Words, Jonathan Nossiter (USA) A sense of the Gothic also infiltrates No Room at the Inn set in the early months of 1940. We witness atmospheric blitzed streets by the railway bridge next to a rundown house that’s definitely on the wrong side of the tracks: all lorded over by Mrs Agatha Voray (Freda Jackson) doing her damn best not to properly look after three young girl evacuees. The children live in squalor and suffer mental and physical abuse under the care of this coarse woman who invites men (local councillors and shopkeepers) for casual sex and bit of cash to bolster her shopping allowance of ration coupons.

A sense of the Gothic also infiltrates No Room at the Inn set in the early months of 1940. We witness atmospheric blitzed streets by the railway bridge next to a rundown house that’s definitely on the wrong side of the tracks: all lorded over by Mrs Agatha Voray (Freda Jackson) doing her damn best not to properly look after three young girl evacuees. The children live in squalor and suffer mental and physical abuse under the care of this coarse woman who invites men (local councillors and shopkeepers) for casual sex and bit of cash to bolster her shopping allowance of ration coupons.

Dir.: Georgui Balabanov; Documentary with Christo, Jeanne-Claude, Anani Yavashev; Bulgaria 1996, 72 min.

Dir.: Georgui Balabanov; Documentary with Christo, Jeanne-Claude, Anani Yavashev; Bulgaria 1996, 72 min. The inspirational tenet of the Cistercian monks is simplicity. Life in a monastery is not an escape route from the world. Apart from running the monastery and brewing, the monks lives are spent in deep contemplation, silencing their minds and stripping back their own desires and thoughts and offer themselves to God in prayer. Not to be confused with meditation that has as its focus green fields, beaches or or the next holiday: the monks are taught to empty their minds so as to make room for God’s presence. Their existence is enriched by the simplicity of their lives and not their material wealth.

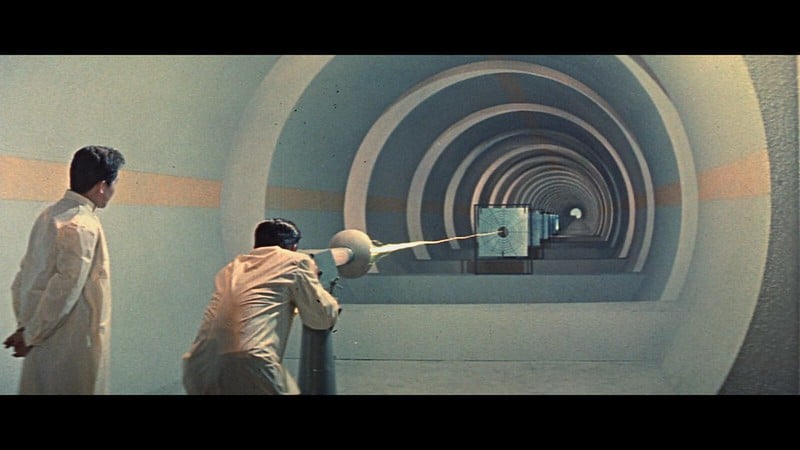

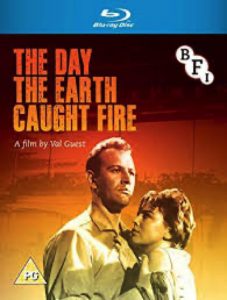

The inspirational tenet of the Cistercian monks is simplicity. Life in a monastery is not an escape route from the world. Apart from running the monastery and brewing, the monks lives are spent in deep contemplation, silencing their minds and stripping back their own desires and thoughts and offer themselves to God in prayer. Not to be confused with meditation that has as its focus green fields, beaches or or the next holiday: the monks are taught to empty their minds so as to make room for God’s presence. Their existence is enriched by the simplicity of their lives and not their material wealth. Valmond Maurice Guest (1911-2006) was an English film director and screenwriter who started his career on the British stage and in early sound films. He wrote over 70 scripts many of which he also directed, developing a versatile talent for making quality genre fare on a limited budget (Hell is a City, Casino Royale, The Boys in Blue). But Guest was best known for his Hammer horror pictures The Quatermass Xperiment and Quatermass II, and Sci-Fis The Day the Earth Caught Fire and 80,000 Suspects which nowadays provide a fascinating snapshot of London and Bath in the early Sixties. Shot luminously in black and white CinemaScope the film incorporates archive footage that feels surprisingly effective with views of Battersea Power Station and London Bridge. A brief radio clip from a soundalike PM Harold MacMillan adds to the fun.

Valmond Maurice Guest (1911-2006) was an English film director and screenwriter who started his career on the British stage and in early sound films. He wrote over 70 scripts many of which he also directed, developing a versatile talent for making quality genre fare on a limited budget (Hell is a City, Casino Royale, The Boys in Blue). But Guest was best known for his Hammer horror pictures The Quatermass Xperiment and Quatermass II, and Sci-Fis The Day the Earth Caught Fire and 80,000 Suspects which nowadays provide a fascinating snapshot of London and Bath in the early Sixties. Shot luminously in black and white CinemaScope the film incorporates archive footage that feels surprisingly effective with views of Battersea Power Station and London Bridge. A brief radio clip from a soundalike PM Harold MacMillan adds to the fun.

Elliptical in nature, in the same way as

Elliptical in nature, in the same way as

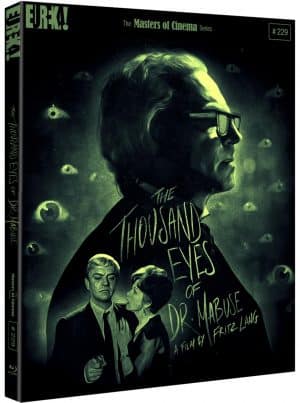

Dir.: Fritz Lang; Cast: Peter van Eyck, Dawn Addams, Gert Fröbe, Werner Peters, Wolfgang Preiss, Lupo Prezzo, Reinhard Kolldehoff; Germany/Italy/France 1960, 103 min.

Dir.: Fritz Lang; Cast: Peter van Eyck, Dawn Addams, Gert Fröbe, Werner Peters, Wolfgang Preiss, Lupo Prezzo, Reinhard Kolldehoff; Germany/Italy/France 1960, 103 min. Films don’t always end up the way their makers originally envisaged at their outset, and the maiden production of Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger’s Archers Films would have turned out completely differently had Laurence Olivier been freed from the Fleet Air Arm to make it; since it is now impossible to imagine without third-billed Roger Livesey and his distinctive voice in the title role (in which at the age of 36 he convincingly ages forty years). The makers’ relative inexperience shows in the fact that they ended up with a initial cut over two and a half hours long; but fortunately J.Arthur Rank liked the film so much he let it hit cinemas as it was. Indeed, it was Pressburger’s favourite of the Rank outings, and would go on to influence the work of future filmmakers such as Scorsese in his The Age of Innocence and Tarantino who copied the device of beginning and ending a film be rerunning the same scene from the point of view of different characters.

Films don’t always end up the way their makers originally envisaged at their outset, and the maiden production of Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger’s Archers Films would have turned out completely differently had Laurence Olivier been freed from the Fleet Air Arm to make it; since it is now impossible to imagine without third-billed Roger Livesey and his distinctive voice in the title role (in which at the age of 36 he convincingly ages forty years). The makers’ relative inexperience shows in the fact that they ended up with a initial cut over two and a half hours long; but fortunately J.Arthur Rank liked the film so much he let it hit cinemas as it was. Indeed, it was Pressburger’s favourite of the Rank outings, and would go on to influence the work of future filmmakers such as Scorsese in his The Age of Innocence and Tarantino who copied the device of beginning and ending a film be rerunning the same scene from the point of view of different characters.

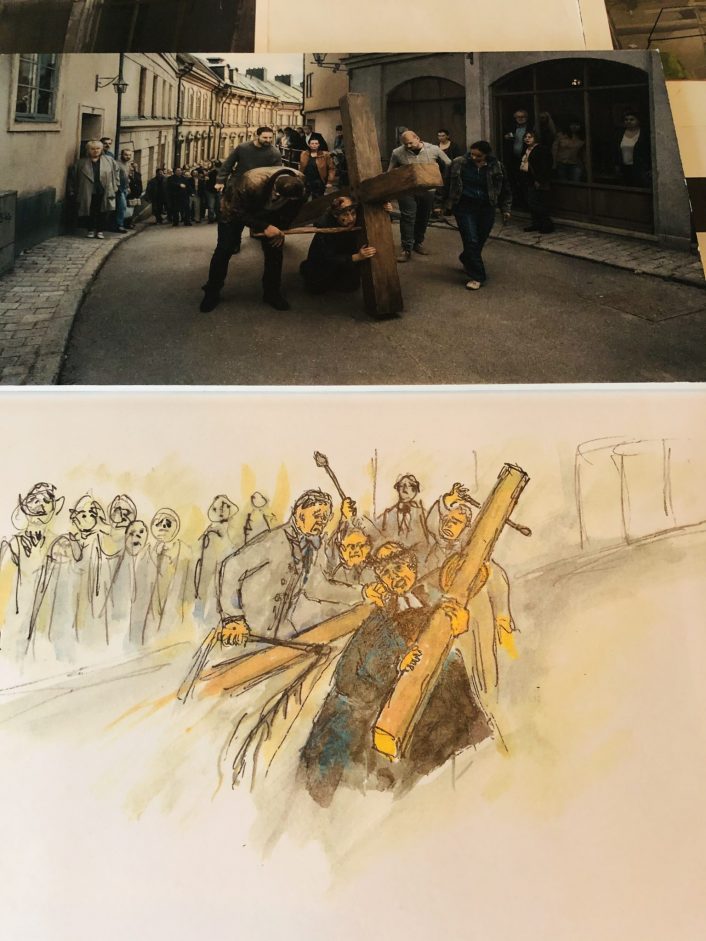

Concise and pithy, this colourful film is narrated on camera by Samuel Aghoyan, the Superior of the Armenian Church, who takes us through a potted history of his own arrival as a child in the Holy City, and gives a sardonic take on the internecine tiffs that add spice to the daily life of this legendary ecclesiastical HQ sitting proudly in the Christian Quarter of the Old City of Jerusalem.

Concise and pithy, this colourful film is narrated on camera by Samuel Aghoyan, the Superior of the Armenian Church, who takes us through a potted history of his own arrival as a child in the Holy City, and gives a sardonic take on the internecine tiffs that add spice to the daily life of this legendary ecclesiastical HQ sitting proudly in the Christian Quarter of the Old City of Jerusalem. According to traditions, dating back to at least the fourth century, the building houses the two holiest sites in Christianity: the site where Jesus was crucified, at a place known as Calvary or Golgotha, and Jesus’s empty tomb, where he was buried and resurrected. The tomb is enclosed by a 19th-century shrine called the Aedicula. According to the history books, Jerusalem has had a chequered and controversial religious past. But eventually 260 years ago, the English were back in town and set up ‘The Status Quo’, an understanding between religious communities that must be respected across the board.

According to traditions, dating back to at least the fourth century, the building houses the two holiest sites in Christianity: the site where Jesus was crucified, at a place known as Calvary or Golgotha, and Jesus’s empty tomb, where he was buried and resurrected. The tomb is enclosed by a 19th-century shrine called the Aedicula. According to the history books, Jerusalem has had a chequered and controversial religious past. But eventually 260 years ago, the English were back in town and set up ‘The Status Quo’, an understanding between religious communities that must be respected across the board.

The Navigator (1924, dir. Buster Keaton & Donald Crisp) – Wealthy Rollo Treadway (Keaton) suddenly decides to propose to his neighbour across the street, Betsy O’Brien (Kathryn McGuire), and sends his servant to book passage for a honeymoon sea cruise to Honolulu. When Betsy rejects his sudden offer however, he decides to go on the trip anyway, boarding without delay that night. Because the pier number is partially covered, he ends up on the wrong ship, the Navigator, which Betsy’s rich father has just sold to a small country at war. Keaton was unhappy with the audience response to Sherlock Jr., and endeavoured to make a follow-up that was both exciting and successful. The result was the biggest hit of Keaton’s career and his personal favourite.

The Navigator (1924, dir. Buster Keaton & Donald Crisp) – Wealthy Rollo Treadway (Keaton) suddenly decides to propose to his neighbour across the street, Betsy O’Brien (Kathryn McGuire), and sends his servant to book passage for a honeymoon sea cruise to Honolulu. When Betsy rejects his sudden offer however, he decides to go on the trip anyway, boarding without delay that night. Because the pier number is partially covered, he ends up on the wrong ship, the Navigator, which Betsy’s rich father has just sold to a small country at war. Keaton was unhappy with the audience response to Sherlock Jr., and endeavoured to make a follow-up that was both exciting and successful. The result was the biggest hit of Keaton’s career and his personal favourite.

Merce was also passionate about working with artists from other disciplines including composer John Cage, Cunningham’s longterm partner; the painter Robert Rauschenberg; and Andy Warhol whose collaboration is particularly striking in Merce’s 1968 Sci-fi themed dance work Rainforest which featured Warhol’s metallic helium-filled silver balloons (the Silver Clouds) that float around the dancers like something from outer space.

Merce was also passionate about working with artists from other disciplines including composer John Cage, Cunningham’s longterm partner; the painter Robert Rauschenberg; and Andy Warhol whose collaboration is particularly striking in Merce’s 1968 Sci-fi themed dance work Rainforest which featured Warhol’s metallic helium-filled silver balloons (the Silver Clouds) that float around the dancers like something from outer space. L

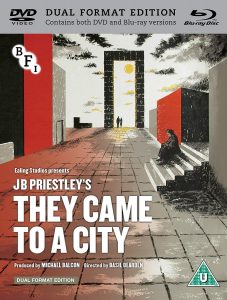

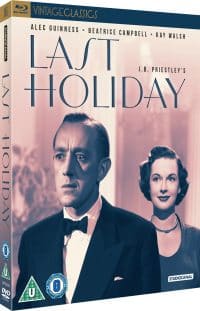

L Dir: James Whale | Wri: Benn Levy/J B Priestley | Cast: Boris Karloff| Charles Laughton | Eva Moore | Gloria Stuart | Melvyn Douglas| Raymond Massey | Horror / Comedy |US 75′

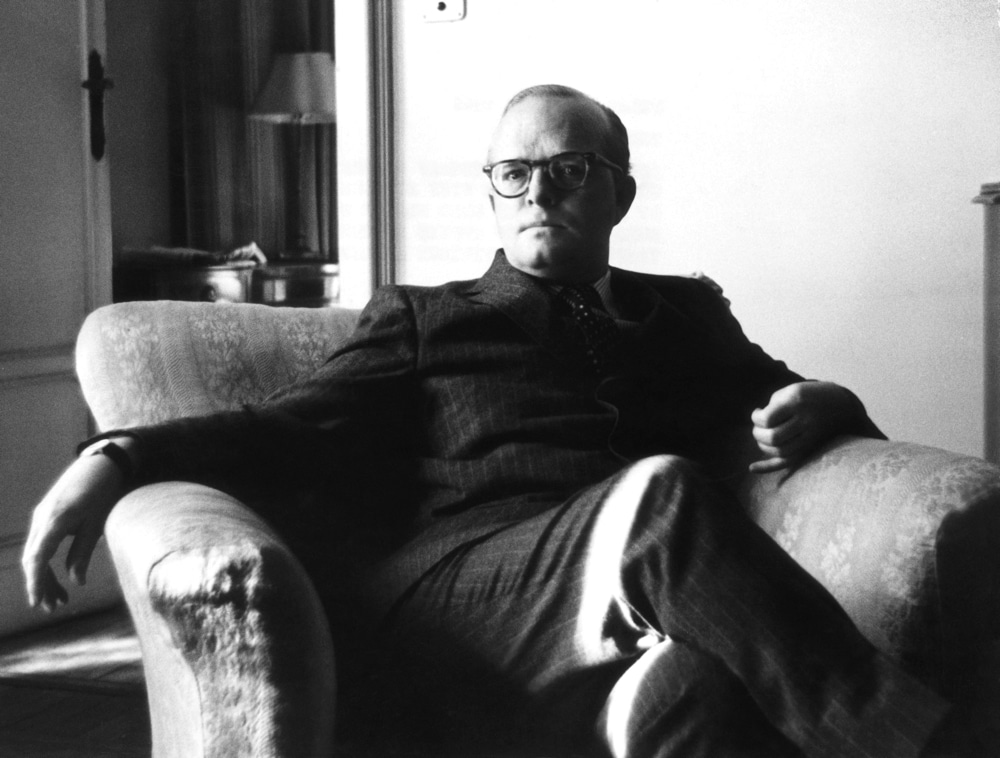

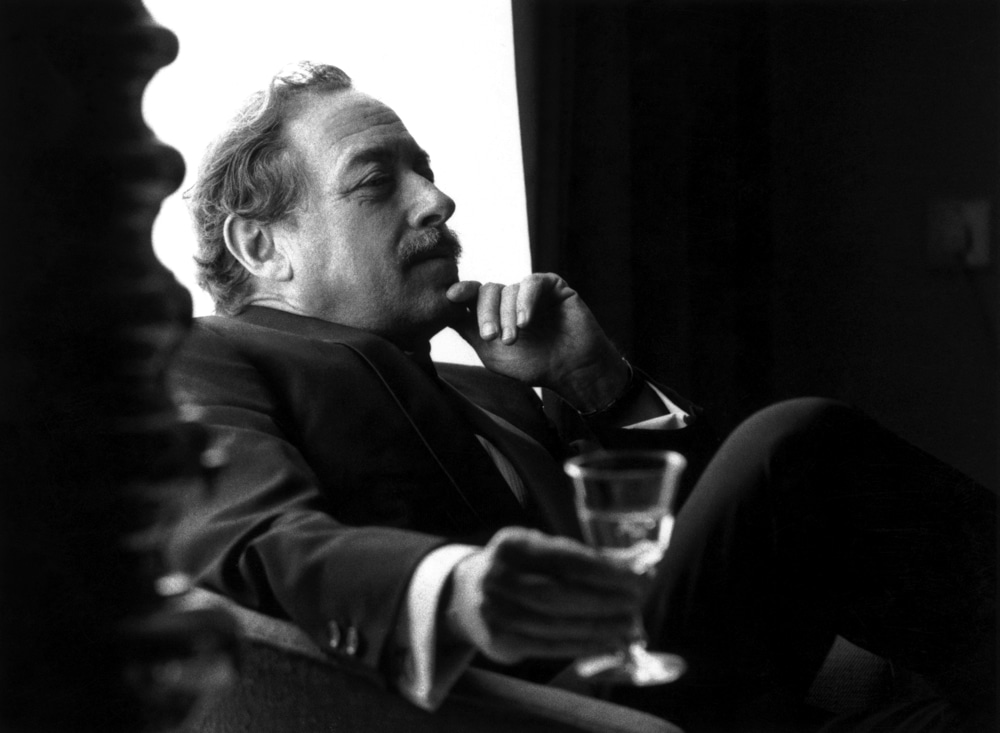

Dir: James Whale | Wri: Benn Levy/J B Priestley | Cast: Boris Karloff| Charles Laughton | Eva Moore | Gloria Stuart | Melvyn Douglas| Raymond Massey | Horror / Comedy |US 75′ Documentary wise: Ebs Burnough’s The Capote Tapes takes us back through the archives to revisit the iconic American novelist, while Nanni Moretti’s Santiago, Italia (left) explores the Italian role in rescuing exiles out of Chile after Pinochet’s Coup d’Etat.

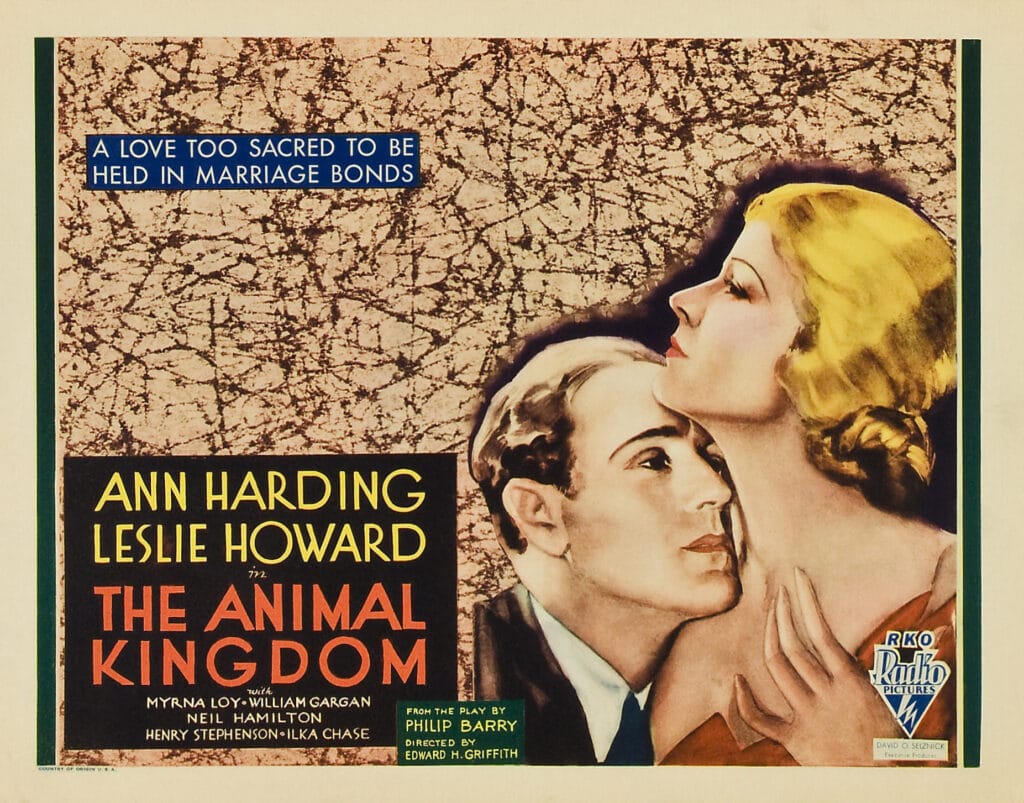

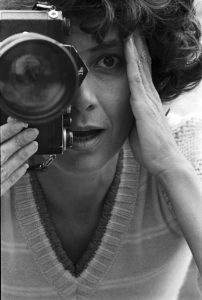

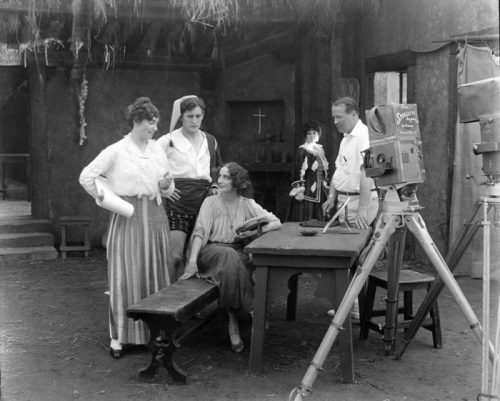

Documentary wise: Ebs Burnough’s The Capote Tapes takes us back through the archives to revisit the iconic American novelist, while Nanni Moretti’s Santiago, Italia (left) explores the Italian role in rescuing exiles out of Chile after Pinochet’s Coup d’Etat.  Women filmmakers will be also championed in Mark Cousins’ 2018 epic homage to the history of female talent: Women Make Film:

Women filmmakers will be also championed in Mark Cousins’ 2018 epic homage to the history of female talent: Women Make Film:

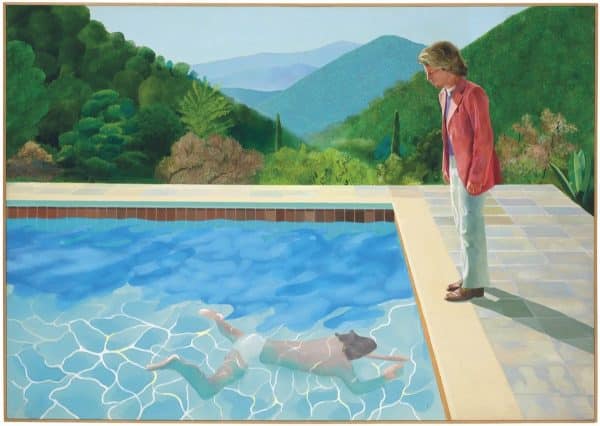

The former artistic director of the Royal Academy Tim Marlow takes us round Lucian Freud’s first and only exhibition at the London gallery (until 26 January 2020). Although Freud is seen as a modern artist his work is very much connected to that ‘old master’, painterly tradition of Titian and Rembrandt: Few modern artists have explored the human body with such intensity, and such determination. Of course, he was a gambler, a playboy and a bon viveur, but few artists spent as much time in their studio as Lucian Freud. The RA’s Andrea Tarsia explains how he pitted his developing style against his personal life, scrutinising himself as much as his subjects. His single-minded passion focused on self-portraiture as much as on those his was painting:. “Everything is a self-portrait”. Often his subjects are not even named: what mattered more to him was the immediacy of the situation, the spontaneity of the gaze. Accompanied by a jazzy score the doc conveys the energy and charisma that seems to spin off each hypnotic portrait, even a small canvas can dominate a room.

The former artistic director of the Royal Academy Tim Marlow takes us round Lucian Freud’s first and only exhibition at the London gallery (until 26 January 2020). Although Freud is seen as a modern artist his work is very much connected to that ‘old master’, painterly tradition of Titian and Rembrandt: Few modern artists have explored the human body with such intensity, and such determination. Of course, he was a gambler, a playboy and a bon viveur, but few artists spent as much time in their studio as Lucian Freud. The RA’s Andrea Tarsia explains how he pitted his developing style against his personal life, scrutinising himself as much as his subjects. His single-minded passion focused on self-portraiture as much as on those his was painting:. “Everything is a self-portrait”. Often his subjects are not even named: what mattered more to him was the immediacy of the situation, the spontaneity of the gaze. Accompanied by a jazzy score the doc conveys the energy and charisma that seems to spin off each hypnotic portrait, even a small canvas can dominate a room. A sensuality entered the artist’s work in the late 1950s and early 1960 where an emphasis on touch starts to appear. This is most noticeable during a trip to Ian Fleming’s Golden Eye when he painted a Flemish style portrait on a small scrap of copper. It sees him putting his finger on his lips and was the start of this sensuous awareness. The 1960s also marked a switch to hog-hair brushes with ‘Man’s Head’ (1963) and the restless associated portraits, smooth backgrounds allowing the face to stand out. Although Freud admired Francis Bacon’s style of working in a gestural way, his own work increasingly gained a more structural, almost architectural element, as he slotted colours together with pasty brushstrokes, trying to make the paint tell the story.

A sensuality entered the artist’s work in the late 1950s and early 1960 where an emphasis on touch starts to appear. This is most noticeable during a trip to Ian Fleming’s Golden Eye when he painted a Flemish style portrait on a small scrap of copper. It sees him putting his finger on his lips and was the start of this sensuous awareness. The 1960s also marked a switch to hog-hair brushes with ‘Man’s Head’ (1963) and the restless associated portraits, smooth backgrounds allowing the face to stand out. Although Freud admired Francis Bacon’s style of working in a gestural way, his own work increasingly gained a more structural, almost architectural element, as he slotted colours together with pasty brushstrokes, trying to make the paint tell the story. Lucian Freud’s large 1993 self-portrait is defiant – he was 71, but still emanated power and excitement; his greatest fear was losing his mind, but he was also concerned about his physical vigour. ‘Benefits Supervisor Sleeping’ (1995) sold in 2008 for 33.6million dollars – the highest price ever paid for a work by a living artist. Freud carried on painting voraciously until his death on 20 July 2011. He was 88. “Being with him was like being plugged into the National Grid for an hour” said one sitter. “Freud was one of the great European painters of the last 500 years. He’s one of those big figures across the centuries, rather than representative of an era or a movement” says Tim Marlow. “Tradition is a big word but Lucian challenged tradition constantly”. Jasper Sharp adds him to a list that goes back to Holbein; Durer; Cranach and Rembrandt. And he goes on: “Freud gives that list a little shuffle, making us look at Rembrandt a bit differently and Holbein a bit differently through his eyes, and through himself”. And that is a remarkable achievement for any artist. MT

Lucian Freud’s large 1993 self-portrait is defiant – he was 71, but still emanated power and excitement; his greatest fear was losing his mind, but he was also concerned about his physical vigour. ‘Benefits Supervisor Sleeping’ (1995) sold in 2008 for 33.6million dollars – the highest price ever paid for a work by a living artist. Freud carried on painting voraciously until his death on 20 July 2011. He was 88. “Being with him was like being plugged into the National Grid for an hour” said one sitter. “Freud was one of the great European painters of the last 500 years. He’s one of those big figures across the centuries, rather than representative of an era or a movement” says Tim Marlow. “Tradition is a big word but Lucian challenged tradition constantly”. Jasper Sharp adds him to a list that goes back to Holbein; Durer; Cranach and Rembrandt. And he goes on: “Freud gives that list a little shuffle, making us look at Rembrandt a bit differently and Holbein a bit differently through his eyes, and through himself”. And that is a remarkable achievement for any artist. MT

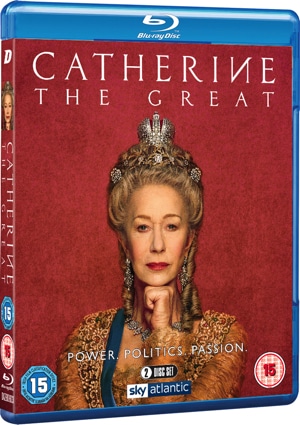

Catherine the Great

Catherine the Great AN ELEPHANT SITTING STILL (2019)

AN ELEPHANT SITTING STILL (2019) SON OF SAUL (2015) Laszlo Nemez

SON OF SAUL (2015) Laszlo Nemez Dir|Wri: Nicolás Rincón Gille | Doc 136′ | Columbia, Belgium

Dir|Wri: Nicolás Rincón Gille | Doc 136′ | Columbia, Belgium Dir: Blake Edwards | Cast: Cary Grant, Tony Curtis, Joan O’Brien, Dina Merrill, Gene Evans, Dick Sargent (TV’s Bewitched) | US Drama 124′

Dir: Blake Edwards | Cast: Cary Grant, Tony Curtis, Joan O’Brien, Dina Merrill, Gene Evans, Dick Sargent (TV’s Bewitched) | US Drama 124′

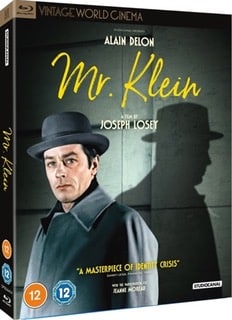

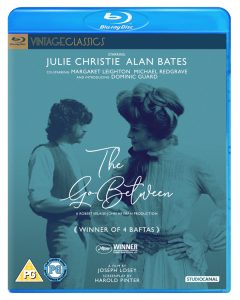

Losey’s adaptation of LP Hartley’s novel is arguably his masterpiece. Pinter’s script adds a darkly amusing twist to the torrid love and coming of age story set in the lush summer landscapes of Norfolk to Michel Legrand’s iconic score.

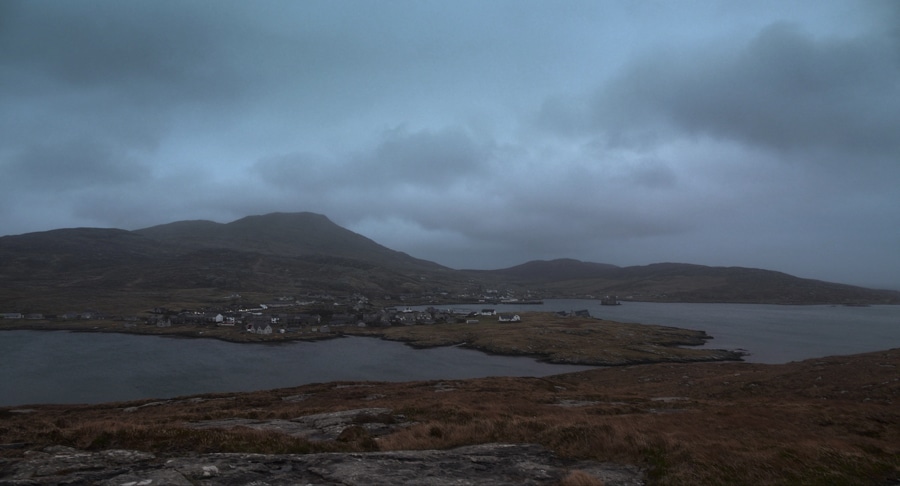

Losey’s adaptation of LP Hartley’s novel is arguably his masterpiece. Pinter’s script adds a darkly amusing twist to the torrid love and coming of age story set in the lush summer landscapes of Norfolk to Michel Legrand’s iconic score. Joanna Hogg is the only living female filmmaker who portrays a particular English contemporary milieu. Usually creative, invariably white and well-educated, these characters are liberal in outlook and mostly live in London. With such unique sensibilities and vision she is able to understand and convey as certain type of middle class angst (borne out of having to do the right thing, irrespective of personal choice). She did it gracefully in Unrelated (2007), Archipelago (2010) and Exhibition (2013), And she does it peerlessly again here with The Souvenir, a nuanced and delicately drawn story of addiction and strained relationships that very much echoes its time and place: the late 1980s – although it was inspired and takes its name from Fragonard’s painting, a motif that runs through the film.

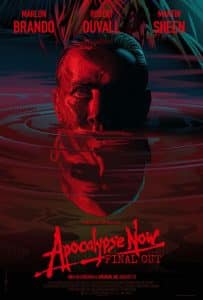

Joanna Hogg is the only living female filmmaker who portrays a particular English contemporary milieu. Usually creative, invariably white and well-educated, these characters are liberal in outlook and mostly live in London. With such unique sensibilities and vision she is able to understand and convey as certain type of middle class angst (borne out of having to do the right thing, irrespective of personal choice). She did it gracefully in Unrelated (2007), Archipelago (2010) and Exhibition (2013), And she does it peerlessly again here with The Souvenir, a nuanced and delicately drawn story of addiction and strained relationships that very much echoes its time and place: the late 1980s – although it was inspired and takes its name from Fragonard’s painting, a motif that runs through the film. In celebration of its 40 year anniversary Apocalypse Now Final Cut, offers a chance to see the full 180 minute version for the first time ever. Coppola’s spectacular cinematic masterpiece on the big screen and in a Blu-ray version.

In celebration of its 40 year anniversary Apocalypse Now Final Cut, offers a chance to see the full 180 minute version for the first time ever. Coppola’s spectacular cinematic masterpiece on the big screen and in a Blu-ray version.

MARIE-LOUISE IRIBE Parisian actress and filmmaker, Marie Louise Iribe (1894-1934) had a short but dazzling career and is best known for her 1928 debut Hara-Kiri (co-directed with Henri Debain). Her follow-up Le Roi de Aulnes (1931) is based on a poem by Goethe. This enchanting filigree fairy tale has the same magical touch and look as Cocteau’s La Belle et la Bête which followed 15 years later and during wartime. The simple but moving storyline sees a man riding through hill and dale to carry his injured son home. As he slips in an out of consciousness the boy imagines death as a mythical king surrounded by wood nymphs. Emile Pierre delicately overlays the forest journey with ethereal images of the king in iridescent armour, transformed from a humble toad realised by DoP Emilie Pierre’s ethereal double exposures. Max D’Ollone’s atmospheric score brings the magic to life.

MARIE-LOUISE IRIBE Parisian actress and filmmaker, Marie Louise Iribe (1894-1934) had a short but dazzling career and is best known for her 1928 debut Hara-Kiri (co-directed with Henri Debain). Her follow-up Le Roi de Aulnes (1931) is based on a poem by Goethe. This enchanting filigree fairy tale has the same magical touch and look as Cocteau’s La Belle et la Bête which followed 15 years later and during wartime. The simple but moving storyline sees a man riding through hill and dale to carry his injured son home. As he slips in an out of consciousness the boy imagines death as a mythical king surrounded by wood nymphs. Emile Pierre delicately overlays the forest journey with ethereal images of the king in iridescent armour, transformed from a humble toad realised by DoP Emilie Pierre’s ethereal double exposures. Max D’Ollone’s atmospheric score brings the magic to life.

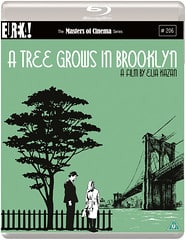

Dir: Elia Kazan | Drama | US

Dir: Elia Kazan | Drama | US Dutch landscape designer and plantsman Pete Oudolf has dedicated his life to creating some of the most iconic gardens around the world and this documentary celebrates his contributions in the US and England.

Dutch landscape designer and plantsman Pete Oudolf has dedicated his life to creating some of the most iconic gardens around the world and this documentary celebrates his contributions in the US and England.