The first major international festival of the independent film world: SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL 2016 has wrapped with another “great step forward for independent film,” according to the festival director John Cooper. For ten days in January the snow-bound hub of Park City, Utah screened 120 features, 98 of which are world premieres and include a romantic drama about Barack and Michelle Obama’s first date; a two hander about a drifter who befriends a dead body and the first film to focus on the women of Wall Street.

The first major international festival of the independent film world: SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL 2016 has wrapped with another “great step forward for independent film,” according to the festival director John Cooper. For ten days in January the snow-bound hub of Park City, Utah screened 120 features, 98 of which are world premieres and include a romantic drama about Barack and Michelle Obama’s first date; a two hander about a drifter who befriends a dead body and the first film to focus on the women of Wall Street.

So what’s new trendwise in 2016? Well, according to director of programming Trevor Groth: Everyone’s understanding craft so much better. There’s a changing face to what a documentary is and what it can do in the end. People are experimenting in genre in really interesting ways, so festival-goers should expect a “wild range of tones and styles” in the World Cinema dramatic competition. “Independent filmmakers are doing what they’ve always done best: connecting the dots of human existence with a deeply charged emotional current.” We look at the ones that screened during this year’s festival and the PRIZE WINNERS to look out for in the coming months.

US DRAMATIC COMPETITION winner THE BIRTH OF A NATION (US)

US DIRECTING AWARD DRAMATIC winner SWISS ARMY MAN (US)

US DOCUMENTARY COMPETITION winner WEINER

US DIRECTING AWARD DOCUMENTARY winner LIFE, ANIMATED (US)

WORLD CINEMA DRAMATIC COMPETITION winner SAND STORM (ISRAEL)

WORLD CINEMA DIRECTING AWARD DRAMATIC winner BELGICA (BELGIUM)

WORLD CINEMA DOCUMENTARY COMPETITION winner SONITA (IRAN)

WORLD CINEMA DIRECTING AWARD DOCUMENTARY winner ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS (POLAND)

ALFRED P SLOAN FEATURE FILM PRIZE winner EMBRACE OF THE SERPENT (MEXICO)

WORLD CINEMA AWARD FOR UNIQUE VISION AND DESIGN winner THE LURE (POLAND)

NEXT -AUDIENCE AWARD winner THE FIRST GIRL I LOVED (cutting edge equivalent of Cannes “Un Certain Regard”)

W O R L D P R E M I E R E S

A showcase of world premieres of some of the most highly anticipated narrative films of the coming year.

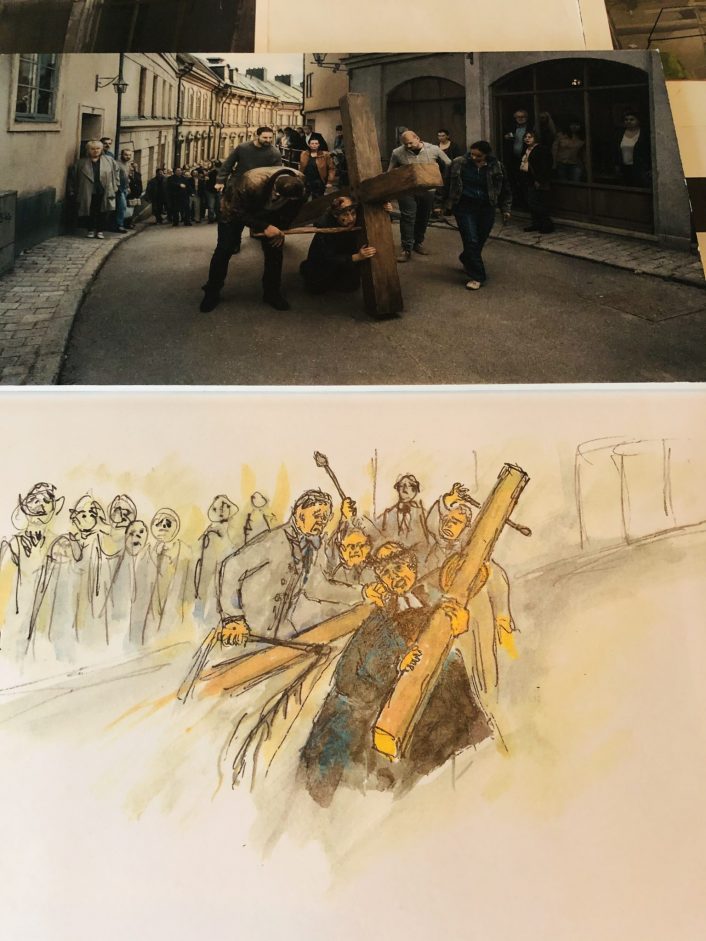

AGNUS DEI / France, Poland (Director: Anne Fontaine, Screenwriters: Sabrina N. Karine, Alice Vial, Pascal Bonitzer) — 1945 Poland: Mathilde, a young French doctor, is on a mission to help World War II survivors. When a nun seeks her assistance in helping several pregnant nuns in hiding, who are unable to reconcile their faith with their pregnancies, Mathilde becomes their only hope. Cast: Lou de Laâge, Agata Kulesza, Agata Buzek, Vincent Macaigne, Joanna Kulig, Katarzyna Dabrowska. World Premiere

AGNUS DEI / France, Poland (Director: Anne Fontaine, Screenwriters: Sabrina N. Karine, Alice Vial, Pascal Bonitzer) — 1945 Poland: Mathilde, a young French doctor, is on a mission to help World War II survivors. When a nun seeks her assistance in helping several pregnant nuns in hiding, who are unable to reconcile their faith with their pregnancies, Mathilde becomes their only hope. Cast: Lou de Laâge, Agata Kulesza, Agata Buzek, Vincent Macaigne, Joanna Kulig, Katarzyna Dabrowska. World Premiere

ALI AND NINO / United Kingdom (Director: Asif Kapadia, Screenwriter: Christopher Hampton) — Muslim prince Ali and Georgian aristocrat Nino have grown up in the Russian province of Azerbaijan. Their tragic love story sees the outbreak of the First World War and the world’s struggle for Baku’s oil. Ultimately they must choose to fight for their country’s independence or for each other. Cast: Adam Bakri, Maria Valverde, Mandy Patinkin, Connie Nielsen, Riccardo Scamarcio, Homayoun Ershadi. World Premiere

ALI AND NINO / United Kingdom (Director: Asif Kapadia, Screenwriter: Christopher Hampton) — Muslim prince Ali and Georgian aristocrat Nino have grown up in the Russian province of Azerbaijan. Their tragic love story sees the outbreak of the First World War and the world’s struggle for Baku’s oil. Ultimately they must choose to fight for their country’s independence or for each other. Cast: Adam Bakri, Maria Valverde, Mandy Patinkin, Connie Nielsen, Riccardo Scamarcio, Homayoun Ershadi. World Premiere

CAPTAIN FANTASTIC / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Matt Ross) — Deep in the forests of the Pacific Northwest, a father devoted to raising his six kids with a rigorous physical and intellectual education is forced to leave his paradise and re-enter society, beginning a journey that challenges his idea of what it means to be a parent. Cast: Viggo Mortensen, Frank Langella, George MacKay, Kathryn Hahn, Steve Zahn, Ann Dowd. World Premiere

CERTAIN WOMEN / U.S.A. (Director: Kelly Reichardt, Screenwriter: Kelly Reichardt based on stories by Maile Meloy) — The lives of three woman intersect in small-town America, where each is imperfectly blazing a trail. Cast: Laura Dern, Kristen Stewart, Michelle Williams, James Le Gros, Jared Harris, Lily Gladstone. World Premiere

CERTAIN WOMEN / U.S.A. (Director: Kelly Reichardt, Screenwriter: Kelly Reichardt based on stories by Maile Meloy) — The lives of three woman intersect in small-town America, where each is imperfectly blazing a trail. Cast: Laura Dern, Kristen Stewart, Michelle Williams, James Le Gros, Jared Harris, Lily Gladstone. World Premiere

COMPLETE UNKNOWN / U.S.A. (Director: Joshua Marston, Screenwriters: Joshua Marston, Julian Sheppard) — When Tom and his wife host a dinner party to celebrate his birthday, one of their friends brings a date named Alice. Tom is convinced he knows her, but she’s going by a different name and a different biography—and she’s not acknowledging that she knows him. Cast: Rachel Weisz, Michael Shannon, Kathy Bates, Danny Glover. World Premiere

FRANK AND LOLA / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Matthew Ross) — A psychosexual noir love story—set in Las Vegas and Paris—about love, obsession, sex, betrayal, revenge and, ultimately, the search for redemption. Cast: Michael Shannon, Imogen Poots, Michael Nyqvist, Justin Long, Emmanuelle Devos, Rosanna Arquette. World Premiere

THE FUNDAMENTALS OF CARING / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Rob Burnett) — Having suffered a tragedy, Ben becomes a caregiver to earn money. His first client, Trevor, is a hilarious 18-year-old with muscular dystrophy. One paralyzed emotionally, one paralyzed physically, Ben and Trevor hit the road, finding hope, friendship, and Dot in this funny and touching inspirational tale. Cast: Paul Rudd, Craig Roberts, Selena Gomez, Jennifer Ehle, Megan Ferguson, Frederick Weller. World Premiere. CLOSING NIGHT FILM

THE HOLLARS / U.S.A. (Director: John Krasinski, Screenwriter: Jim Strouse) — Aspiring New York City artist John Hollar returns to his Middle America hometown on the eve of his mother’s brain surgery. Joined by his girlfriend, eight months pregnant with their first child, John is forced to navigate the crazy world he left behind. Cast: John Krasinski, Anna Kendrick, Margo Martindale, Richard Jenkins, Sharlto Copley, Charlie Day. World Premiere

THE HOLLARS / U.S.A. (Director: John Krasinski, Screenwriter: Jim Strouse) — Aspiring New York City artist John Hollar returns to his Middle America hometown on the eve of his mother’s brain surgery. Joined by his girlfriend, eight months pregnant with their first child, John is forced to navigate the crazy world he left behind. Cast: John Krasinski, Anna Kendrick, Margo Martindale, Richard Jenkins, Sharlto Copley, Charlie Day. World Premiere

HUNT FOR THE WILDERPEOPLE / New Zealand (Director and screenwriter: Taika Waititi) — Ricky is a defiant young city kid who finds himself on the run with his cantankerous foster uncle in the wild New Zealand bush. A national manhunt ensues, and the two are forced to put aside their differences and work together to survive in this heartwarming adventure comedy. Cast: Julian Dennison, Sam Neill, Rima Te Wiata, Rachel House, Oscar Kightley. World Premiere

INDIGNATION / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: James Schamus) — It’s 1951, and among the new arrivals at Winesburg College in Ohio are the son of a kosher butcher from New Jersey and the beautiful, brilliant daughter of a prominent alum. For a brief moment, their lives converge in this emotionally soaring film based on the novel by Philip Roth. Cast: Logan Lerman, Sarah Gadon, Tracy Letts, Linda Emond, Danny Burstein, Ben Rosenfield. World Premiere

INDIGNATION / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: James Schamus) — It’s 1951, and among the new arrivals at Winesburg College in Ohio are the son of a kosher butcher from New Jersey and the beautiful, brilliant daughter of a prominent alum. For a brief moment, their lives converge in this emotionally soaring film based on the novel by Philip Roth. Cast: Logan Lerman, Sarah Gadon, Tracy Letts, Linda Emond, Danny Burstein, Ben Rosenfield. World Premiere

LITTLE MEN / U.S.A. (Director: Ira Sachs, Screenwriter: Mauricio Zacharias) — When 13-year-old Jake’s grandfather dies, his family moves back into their old Brooklyn home. There, Jake befriends Tony, whose single Chilean mother runs the shop downstairs. As their friendship deepens, however, their families are driven apart by a battle over rent, and the boys respond with a vow of silence. Cast: Greg Kinnear, Jennifer Ehle, Paulina Garcia, Theo Taplitz, Michael Barbieri. World Premiere

LOVE AND FRIENDSHIP / Ireland, France, Netherlands (Director and screenwriter: Whit Stillman) — From Jane Austen’s novella, the beautiful and cunning Lady Susan Vernon visits the estate of her in-laws to wait out colorful rumors of her dalliances and to find husbands for herself and her daughter. Two young men, handsome Reginald DeCourcy and wealthy Sir James Martin, severely complicate her plans. Cast: Kate Beckinsale, Chloë Sevigny, Xavier Samuel, Emma Greenwell, Tom Bennett, Stephen Fry. World Premiere

LOVE AND FRIENDSHIP / Ireland, France, Netherlands (Director and screenwriter: Whit Stillman) — From Jane Austen’s novella, the beautiful and cunning Lady Susan Vernon visits the estate of her in-laws to wait out colorful rumors of her dalliances and to find husbands for herself and her daughter. Two young men, handsome Reginald DeCourcy and wealthy Sir James Martin, severely complicate her plans. Cast: Kate Beckinsale, Chloë Sevigny, Xavier Samuel, Emma Greenwell, Tom Bennett, Stephen Fry. World Premiere

MANCHESTER BY THE SEA / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Kenneth Lonergan) — After his older brother passes away, Lee Chandler is forced to return home to care for his 16-year-old nephew. There he is compelled to deal with a tragic past that separated him from his family and the community where he was born and raised. Cast: Casey Affleck, Michelle Williams, Lucas Hedges, Kyle Chandler. World Premiere

MANCHESTER BY THE SEA / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Kenneth Lonergan) — After his older brother passes away, Lee Chandler is forced to return home to care for his 16-year-old nephew. There he is compelled to deal with a tragic past that separated him from his family and the community where he was born and raised. Cast: Casey Affleck, Michelle Williams, Lucas Hedges, Kyle Chandler. World Premiere

MR PIG / Mexico (Director: Diego Luna, Screenwriters: Augusto Mendoza, Diego Luna) — On a mission to sell his last remaining prize hog and reunite with old friends, an aging farmer abandons his foreclosed farm and journeys to Mexico. After smuggling in the hog, his estranged daughter shows up, forcing them to face their past and embark on an adventurous road trip together. Cast: Danny Glover, Maya Rudolph, José María Yazpik, Joel Murray, Angélica Aragón, Gabriela Araujo. World Premiere

SING STREET / Ireland (Director and screenwriter: John Carney) — A boy growing up in Dublin during the ’80s escapes his strained family life and tough new school by starting a band to win the heart of a beautiful and mysterious girl. Cast: Ferdia Walsh-Peelo, Lucy Boynton, Jack Reynor, Aidan Gillen, Mark McKenna. World Premiere

SOPHIE AND THE RISING SUN / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Maggie Greenwald) — In a small Southern town in the autumn of 1941, Sophie’s lonely life is transformed when an Asian man arrives under mysterious circumstances. Their love affair becomes the lightning rod for long-buried conflicts that erupt in bigotry and violence with the outbreak of World War ll. Cast: Julianne Nicholson, Margo Martindale, Lorraine Toussaint, Takashi Yamaguchi, Diane Ladd, Joel Murray. World Premiere. SALT LAKE CITY GALA FILM

SOPHIE AND THE RISING SUN / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Maggie Greenwald) — In a small Southern town in the autumn of 1941, Sophie’s lonely life is transformed when an Asian man arrives under mysterious circumstances. Their love affair becomes the lightning rod for long-buried conflicts that erupt in bigotry and violence with the outbreak of World War ll. Cast: Julianne Nicholson, Margo Martindale, Lorraine Toussaint, Takashi Yamaguchi, Diane Ladd, Joel Murray. World Premiere. SALT LAKE CITY GALA FILM

WIENER DOG / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Todd Solondz) — This film tells several stories featuring people who find their life inspired or changed by one particular dachshund, who seems to be spreading comfort and joy. Cast: Greta Gerwig, Kieran Culkin, Danny DeVito, Ellen Burstyn, Julie Delpy, Zosia Mamet. World Premiere

D O C U M E N T A R Y P R E M I E R E S

Renowned filmmakers and films about far-reaching subjects comprise this section highlighting our ongoing commitment to documentaries.

EAT THAT QUESTION—Frank Zappa in His Own Words / France, Germany (Director: Thorsten Schütte) — This entertaining encounter with the premier of sonic avant-garde is acidic, fun-poking, and full of rich and rare archival footage. This documentary bashes favorite Zappa targets and dashes a few myths about the man himself. World Premiere

FILM HAWK / U.S.A. (Directors: JJ Garvine, Tai Parquet) — Trace Bob Hawk’s early years as the young gay child of a Methodist minister to his current career as a consultant on some of the most influential independent films of our time. World Premiere

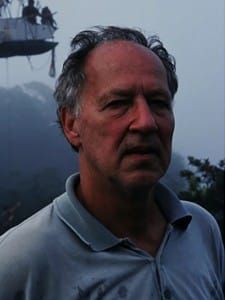

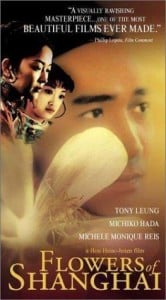

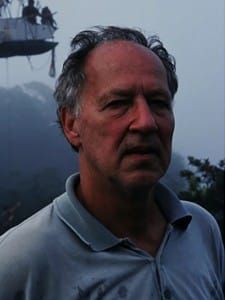

LO AND BEHOLD, Reveries of the Connected World / U.S.A. (Director: Werner Herzog) — Does the internet dream of itself? Explore the horizons of the connected world. World Premiere

LO AND BEHOLD, Reveries of the Connected World / U.S.A. (Director: Werner Herzog) — Does the internet dream of itself? Explore the horizons of the connected world. World Premiere

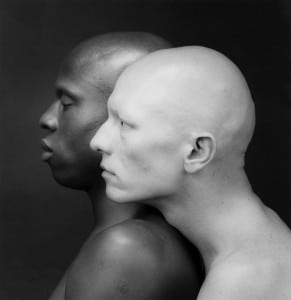

MAPPLETHORPE – LOOK AT THE PICTURES / U.S.A. (Directors: Fenton Bailey, Randy Barbato) — This examination of Robert Mapplethorpe’s outrageous life is led by the artist himself, speaking with brutal honesty in a series of rediscovered interviews about his passions. Intimate revelations from friends, family, and lovers shed new light on this scandalous artist who ignited a culture war that still rages on. World Premiere

MAYA ANGELOU – AND STILL I RISE / U.S.A. (Directors: Bob Hercules, Rita Coburn Whack) — The remarkable story of Maya Angelou — iconic writer, poet, actress and activist whose life has intersected some of the most profound moments in recent American history. World Premiere

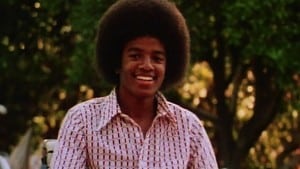

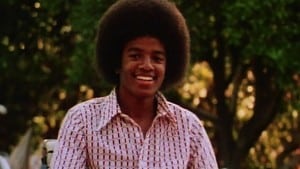

MICHAEL JACKSON’S JOURNEY FROM MOTOWN TO OFF THE WALL / U.S.A. (Director: Spike Lee) — Catapulted by the success of his first major solo project, Off the Wall, Michael Jackson went from child star to King of Pop. This film explores the seminal album, with rare archival footage and interviews from those who were there and those whose lives its success and legacy impacted. World Premiere

MICHAEL JACKSON’S JOURNEY FROM MOTOWN TO OFF THE WALL / U.S.A. (Director: Spike Lee) — Catapulted by the success of his first major solo project, Off the Wall, Michael Jackson went from child star to King of Pop. This film explores the seminal album, with rare archival footage and interviews from those who were there and those whose lives its success and legacy impacted. World Premiere

NORMAN LEAR – Just Another Version of You / U.S.A. (Directors: Heidi Ewing, Rachel Grady) — How did a poor Jewish kid from Connecticut bring us Archie Bunker and become one of the most successful television producers ever? Norman Lear brought provocative subjects like war, poverty, and prejudice into 120 million homes every week. He proved that social change was possible through an unlikely prism: laughter. World Premiere. DAY ONE FILM

NOTHING LEFT UNSAID: Gloria Vanderbilt & Anderson Cooper / U.S.A. (Director: Liz Garbus) — Gloria Vanderbilt and her son Anderson Cooper each tell the story of their past and present, their loves and losses, and reveal how some family stories have the tendency to repeat themselves in the most unexpected ways. World Premiere

NOTHING LEFT UNSAID: Gloria Vanderbilt & Anderson Cooper / U.S.A. (Director: Liz Garbus) — Gloria Vanderbilt and her son Anderson Cooper each tell the story of their past and present, their loves and losses, and reveal how some family stories have the tendency to repeat themselves in the most unexpected ways. World Premiere

RESILIENCE / U.S.A. (Director: James Redford) — This film chronicles the birth of a new movement among pediatricians, therapists, educators, and communities using cutting-edge brain science to disrupt cycles of violence, addiction, and disease. These professionals help break the cycles of adversity by daring to talk about the effects of divorce, abuse, and neglect. World Premiere

RICHARD LINKLATER—dream is destiny / U.S.A. (Directors: Louis Black, Karen Bernstein) — This is an unconventional look at a fiercely independent style of filmmaking that arose in the 1990s from Austin, Texas, outside the studio system. The film blends rare archival footage with journals, exclusive interviews with Linklater on and off set, and clips from Slacker, Dazed and Confused, Boyhood, and more. World Premiere

UNDER THE GUN / U.S.A. (Director: Stephanie Soechtig) — The Sandy Hook massacre was considered a watershed moment in the national debate on gun control, but the body count at the hands of gun violence has only increased. Through the lens of the victims’ families, as well as pro-gun advocates, we examine why our politicians have failed to act. World Premiere

UNLOCKING THE CAGE / U.S.A. (Directors: Chris Hegedus, Donn Alan Pennebaker) — Follow animal rights lawyer Steven Wise in his unprecedented challenge to break down the legal wall that separates animals from humans. By filing the first lawsuit of its kind, Wise seeks to transform a chimpanzee from a “thing” with no rights to a “person” with basic legal protection. World Premiere

U. S . D R A M A T I C C O M P E T I T I O N

The 16 films in this section are world premieres and, unless otherwise noted, are from the U.S.

AS YOU ARE (Director: Miles Joris-Peyrafitte, Screenwriters: Miles Joris-Peyrafitte, Madison Harrison) — The telling and retelling of a relationship between three teenagers as it traces the course of their friendship through a construction of disparate memories prompted by a police investigation. Cast: Owen Campbell, Charlie Heaton, Amandla Stenberg, John Scurti, Scott Cohen, Mary Stuart Masterson.

THE BIRTH OF A NATION (Director and screenwriter: Nate Parker) — Set against the antebellum South, this story follows Nat Turner, a literate slave and preacher, whose financially strained owner, Samuel Turner, accepts an offer to use Nat’s preaching to subdue unruly slaves. After witnessing countless atrocities against fellow slaves, Nat devises a plan to lead his people to freedom. Cast: Nate Parker, Armie Hammer, Aja Naomi King, Jackie Earle Haley, Gabrielle Union, Mark Boone Jr.

THE BIRTH OF A NATION (Director and screenwriter: Nate Parker) — Set against the antebellum South, this story follows Nat Turner, a literate slave and preacher, whose financially strained owner, Samuel Turner, accepts an offer to use Nat’s preaching to subdue unruly slaves. After witnessing countless atrocities against fellow slaves, Nat devises a plan to lead his people to freedom. Cast: Nate Parker, Armie Hammer, Aja Naomi King, Jackie Earle Haley, Gabrielle Union, Mark Boone Jr.

CHRISTINE (Director: Antonio Campos, Screenwriter: Craig Shilowich) — In 1974, a female TV news reporter aims for high standards in life and love in Sarasota, Fla. Missing her mark is not an option. This story is based on true events. Cast: Rebecca Hall, Michael C. Hall, Maria Dizzia, Tracy Letts, J. Smith-Cameron.

EQUITY (Director: Meera Menon, Screenwriter: Amy Fox) — A female investment banker, fighting to get a promotion at her competitive Wall Street firm, leads a controversial tech IPO in the post-financial-crisis world, where regulations are tight but pressure to bring in big money remains high. Cast: Anna Gunn, James Purefoy, Sarah Megan Thomas, Alysia Reiner.

EQUITY (Director: Meera Menon, Screenwriter: Amy Fox) — A female investment banker, fighting to get a promotion at her competitive Wall Street firm, leads a controversial tech IPO in the post-financial-crisis world, where regulations are tight but pressure to bring in big money remains high. Cast: Anna Gunn, James Purefoy, Sarah Megan Thomas, Alysia Reiner.

THE FREE WORLD (Director and screenwriter: Jason Lew) — Following his release from a brutal stretch in prison for crimes he didn’t commit, Mo is struggling to adapt to life on the outside. When his world collides with Doris, a mysterious woman with a violent past, he decides to risk his newfound freedom to keep her in his life. Cast: Boyd Holbrook, Elisabeth Moss, Octavia Spencer, Sung Kang, Waleed Zuaiter.

GOAT (Director: Andrew Neel, Screenwriters: David Gordon Green, Andrew Neel, Michael Roberts) — Reeling from a terrifying assault, a 19-year-old boy pledges his brother’s fraternity in an attempt to prove his manhood. What happens there, in the name of “brotherhood,” tests both the boys and their relationship in brutal ways. Cast: Nick Jonas, Ben Schnetzer, Virginia Gardner, Danny Flaherty, Austin Lyon.

THE INTERVENTION (Director and screenwriter: Clea DuVall) — A weekend getaway for four couples takes a sharp turn when one of the couples discovers the entire trip was orchestrated to host an intervention on their marriage. Cast: Melanie Lynskey, Cobie Smulders, Alia Shawkat, Clea DuVall, Natasha Lyonne, Ben Schwartz.

JOSHY(Director and screenwriter: Jeff Baena) — Josh treats what would have been his bachelor party as an opportunity to reconnect with his friends. Cast: Thomas Middleditch, Adam Pally, Alex Ross Perry, Nick Kroll, Brett Gelman, Jenny Slate.

LOVESONG (Director: So Yong Kim, Screenwriters: So Yong Kim, Bradley Rust Gray) — Neglected by her husband, Sarah embarks on an impromptu road trip with her young daughter and her best friend, Mindy. Along the way, the dynamic between the two friends intensifies before circumstances force them apart. Years later, Sarah attempts to rebuild their intimate connection in the days before Mindy’s wedding. Cast: Jena Malone, Riley Keough, Brooklyn Decker, Amy Seimetz, Ryan Eggold, Rosanna Arquette.

LOVESONG (Director: So Yong Kim, Screenwriters: So Yong Kim, Bradley Rust Gray) — Neglected by her husband, Sarah embarks on an impromptu road trip with her young daughter and her best friend, Mindy. Along the way, the dynamic between the two friends intensifies before circumstances force them apart. Years later, Sarah attempts to rebuild their intimate connection in the days before Mindy’s wedding. Cast: Jena Malone, Riley Keough, Brooklyn Decker, Amy Seimetz, Ryan Eggold, Rosanna Arquette.

MORRIS FROM AMERICA (U.S.-Germany / Director and screenwriter: Chad Hartigan) — Thirteen-year-old Morris, a hip-hop-loving American, moves to Heidelberg, Germany, with his father. In this completely foreign land, he falls in love with a local girl, befriends his German tutor-turned-confidant, and attempts to navigate the unique trials and tribulations of adolescence. Cast: Markees Christmas, Craig Robinson, Carla Juri, Lina Keller, Jakub Gierszal, Levin Henning.

OTHER PEOPLE (Director and screenwriter: Chris Kelly) — A struggling comedy writer, fresh from breaking up with his boyfriend, moves to Sacramento to help his sick mother. Living with his conservative father and younger sisters, David feels like a stranger in his childhood home. As his mother worsens, he tries to convince everyone (including himself) he’s “doing OK.” Cast: Jesse Plemons, Molly Shannon, Bradley Whitford, Maude Apatow, Zach Woods, June Squibb. (Day One film)

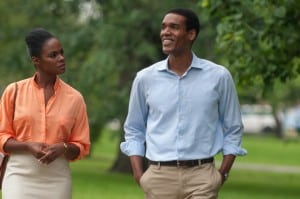

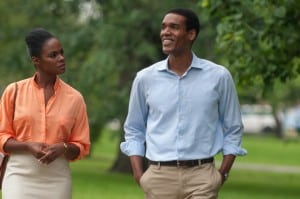

SOUTHSIDE WITH YOU (Director and screenwriter: Richard Tanne) — A chronicle of the summer afternoon in 1989 when the future president of the United States of America, Barack Obama, wooed his future First Lady on an epic first date across Chicago’s South Side. Cast: Tika Sumpter, Parker Sawyers, Vanessa Bell Calloway.

SOUTHSIDE WITH YOU (Director and screenwriter: Richard Tanne) — A chronicle of the summer afternoon in 1989 when the future president of the United States of America, Barack Obama, wooed his future First Lady on an epic first date across Chicago’s South Side. Cast: Tika Sumpter, Parker Sawyers, Vanessa Bell Calloway.

SPA NIGHT (Director and screenwriter: Andrew Ahn) — A young Korean-American man works to reconcile his obligations to his struggling immigrant family with his burgeoning sexual desires in the underground world of gay hookups at Korean spas in Los Angeles. Cast: Joe Seo, Haerry Kim, Youn Ho Cho, Tae Song, Ho Young Chung, Linda Han.

SWISS ARMY MAN (Directors and screenwriters: Daniel Scheinert, Daniel Kwan) — Hank, a hopeless man stranded in the wild, discovers a mysterious dead body. Together the two embark on an epic journey to get home. As Hank realizes the body is the key to his survival, this once-suicidal man is forced to convince a dead body that life is worth living. Cast: Paul Dano, Daniel Radcliffe, Mary Elizabeth Winstead.

SWISS ARMY MAN (Directors and screenwriters: Daniel Scheinert, Daniel Kwan) — Hank, a hopeless man stranded in the wild, discovers a mysterious dead body. Together the two embark on an epic journey to get home. As Hank realizes the body is the key to his survival, this once-suicidal man is forced to convince a dead body that life is worth living. Cast: Paul Dano, Daniel Radcliffe, Mary Elizabeth Winstead.

TALLULAH (Director and screenwriter: Sian Heder) — A rootless young woman takes a toddler from a wealthy, negligent mother and passes the baby off as her own in an effort to protect her. This decision connects and transforms the lives of three very different women. Cast: Ellen Page, Allison Janney, Tammy Blanchard, Evan Jonigkeit, Uzo Aduba.

WHITE GIRL (Director and screenwriter: Elizabeth Wood) — Summer, New York City: A college student goes to extremes to get her drug-dealer boyfriend out of jail. Cast: Morgan Saylor, Brian “Sene” Marc, Justin Bartha, Chris Noth, India Menuez, Adrian Martinez.

WHITE GIRL (Director and screenwriter: Elizabeth Wood) — Summer, New York City: A college student goes to extremes to get her drug-dealer boyfriend out of jail. Cast: Morgan Saylor, Brian “Sene” Marc, Justin Bartha, Chris Noth, India Menuez, Adrian Martinez.

U.S. DOCUMENTARY COMPETITION

The 16 films in this section are world premieres and, unless otherwise noted, are from the U.S.

AUDRIE AND DAISY (Directors: Bonni Cohen, Jon Shenk) — After two high-school girls in different towns are sexually assaulted by boys they consider friends, online bullying leads each girl to attempt suicide. Tragically, one dies. Assault in the social media age is explored from the perspectives of the girls and boys involved, as well as their torn-apart communities.

AUTHOR : The JT LeRoy Story” (Director: Jeff Feuerzeig) — As the definitive look inside the mysterious case of 16-year-old literary sensation JT LeRoy — a creature so perfect for his time that if he didn’t exist, someone would have had to invent him — this is the strangest story about story ever told.

THE BAD KIDS (Directors: Keith Fulton, Lou Pepe) — At a remote Mojave Desert high school, extraordinary educators believe that empathy and life skills, more than academics, give at-risk students command of their own futures. This coming-of-age story watches education combat the crippling effects of poverty in the lives of these so-called “bad kids.”

THE BAD KIDS (Directors: Keith Fulton, Lou Pepe) — At a remote Mojave Desert high school, extraordinary educators believe that empathy and life skills, more than academics, give at-risk students command of their own futures. This coming-of-age story watches education combat the crippling effects of poverty in the lives of these so-called “bad kids.”

GLEASON (Director: Clay Tweel) — At the age of 34, Steve Gleason, former NFL defensive back and New Orleans hero, was diagnosed with ALS. Doctors gave him two to five years to live. So that is what Steve chose to do: Live — both for his wife and newborn son and to help others with this disease.

HOLY HELL (Director: undisclosed) — Just out of college, a young filmmaker joins a loving, secretive, spiritual community led by a charismatic teacher in 1980s West Hollywood. Twenty years later, the group is shockingly torn apart. Told through hundreds of hours of accumulated footage, this is their story.

HOW TO LET GO OF THE WORLD (and Love All the Things Climate Can’t Change)” (Director: Josh Fox) — Do we have a chance to stop the most destructive consequences of climate change, or is it too late? Academy Award-nominated director Josh Fox (“Gasland”) travels to 12 countries on six continents to explore what we have to let go of — and all of the things that climate can’t change.

JIM (Director: Brian Oakes) — The public execution of American conflict journalist James Foley captured the world’s attention, but he was more than just a man in an orange jumpsuit. Seen through the lens of his close childhood friend, “Jim” moves from adrenaline-fueled front lines and devastated neighborhoods of Syria into the hands of ISIS.

KATE PLAYS CHRISTINE (Director: Robert Greene) — This psychological thriller follows actor Kate Lyn Sheil as she prepares to play the role of Christine Chubbuck, a Florida television host who committed suicide on air in 1974. Christine’s tragic death was the inspiration for “Network,” and the mysteries surrounding her final act haunt Kate and the production.

KATE PLAYS CHRISTINE (Director: Robert Greene) — This psychological thriller follows actor Kate Lyn Sheil as she prepares to play the role of Christine Chubbuck, a Florida television host who committed suicide on air in 1974. Christine’s tragic death was the inspiration for “Network,” and the mysteries surrounding her final act haunt Kate and the production.

KIKI (U.S.-Sweden / Director: Sara Jordeno) — Through a strikingly intimate and visually daring lens, “Kiki” offers insight into a safe space created and governed by LGBTQ youths of color, who are demanding happiness and political power. A coming-of-age story about agency, resilience, and the transformative art form of voguing.

LIFE, ANIMATED (Director: Roger Ross Williams) — Owen Suskind, an autistic boy who could not speak for years, slowly emerged from his isolation by immersing himself in Disney animated movies. Using these films as a roadmap, he reconnects with his loving family and the wider world in this emotional coming-of-age story.

NEWTOWN (Director: Kim A. Snyder) — After joining the ranks of a growing club no one wants to belong to, the people of Newtown, Conn., weave an intimate story of resilience. This film traces the aftermath of the worst mass shooting of schoolchildren in American history as the traumatized community finds a new sense of purpose.

NUTS! (Director: Penny Lane) left — The mostly true story of Dr. John Romulus Brinkley, an eccentric genius who built an empire with his goat-testicle impotence cure and a million-watt radio station. Animated re-enactments, interviews, archival footage, and one seriously unreliable narrator trace his rise from poverty to celebrity and influence in 1920s America.

NUTS! (Director: Penny Lane) left — The mostly true story of Dr. John Romulus Brinkley, an eccentric genius who built an empire with his goat-testicle impotence cure and a million-watt radio station. Animated re-enactments, interviews, archival footage, and one seriously unreliable narrator trace his rise from poverty to celebrity and influence in 1920s America.

SUITED (Director: Jason Benjamin) — Bindle & Keep, a Brooklyn tailoring company, makes custom suits for a growing legion of gender-nonconforming clients.

TRAPPED (Director: Dawn Porter) — American abortion clinics are in a fight for survival. Targeted Regulation of Abortion Providers (TRAP) laws are increasingly being passed by states that maintain they ensure women’s safety and health, but as clinics continue to shut their doors, opponents believe the real purpose of these laws is to outlaw abortion.

UNCLE HOWARD” (U.S.-U.K. / Director: Aaron Brookner) — Howard Brookner’s first film, “Burroughs: The Movie,”captured the cultural revolution of downtown New York City in the early ’80s. Twenty-five years after his promising career was cut short by AIDS, his nephew sets out to discover Howard’s never-before-seen films to create a cinematic elegy about his childhood idol.

WEINER (Directors: Josh Kriegman, Elyse Steinberg) — With unrestricted access to Anthony Weiner’s New York City mayoral campaign, this film reveals how a high-profile political scandal unfolds behind the scenes, and it offers an unfiltered look at how much today’s politics are driven by an appetite for spectacle.

WORLD CINEMA DRAMATIC COMPETITION

The 12 films in this section are world premieres unless otherwise specified.

BELGICA right (Belgium-France-Netherlands / Director: Felix van Groeningen, Screenwriters: Felix van Groeningen, Arne Sierens) — In the midst of Belgium’s nightlife scene, two brothers start a bar and get swept up in its success. Cast: Stef Aerts, Tom Vermeir, Charlotte Vandermeersch, Helene De Vos. (Day One film)

BELGICA right (Belgium-France-Netherlands / Director: Felix van Groeningen, Screenwriters: Felix van Groeningen, Arne Sierens) — In the midst of Belgium’s nightlife scene, two brothers start a bar and get swept up in its success. Cast: Stef Aerts, Tom Vermeir, Charlotte Vandermeersch, Helene De Vos. (Day One film)

BETWEEN SEA AND LAND (Colombia / Directors: Manolo Cruz, Carlos del Castillo, Screenwriter: Manolo Cruz) — Alberto, who suffers from an illness that binds him into a body that doesn’t obey him, lives with his loving mom, who dedicates her life to him. His sickness impedes him from achieving his greatest dream of knowing the sea, despite one being located just across the street. Cast: Manolo Cruz, Vicky Hernandez, Viviana Serna, Jorge Cao, Mile Vergara, Javier Saenz.

BRAHMAN NAHMAN (U.K.-India / Director: Q, Screenwriter: S. Ramachandran) — When Bangalore U.’s misfit quiz team manages to get into the national championships, they make an alcohol-fueled, cross-country journey to the competition, determined to defeat their archrivals from Calcutta while all desperately trying to lose their virginity. Cast: Shashank Arora, Tanmay Dhanania, Chaitanya Varad, Vaiswath Shankar, Sindhu Sreenivasa Murthy, Sid Mallya.

BRAHMAN NAHMAN (U.K.-India / Director: Q, Screenwriter: S. Ramachandran) — When Bangalore U.’s misfit quiz team manages to get into the national championships, they make an alcohol-fueled, cross-country journey to the competition, determined to defeat their archrivals from Calcutta while all desperately trying to lose their virginity. Cast: Shashank Arora, Tanmay Dhanania, Chaitanya Varad, Vaiswath Shankar, Sindhu Sreenivasa Murthy, Sid Mallya.

A GOOD WIFE (Serbia-Bosnia-Croatia / Director: Mirjana Karanovic, Screenwriters: Mirjana Karanovic, Stevan Filipovic, Darko Lungulov) — When 50-year-old Milena finds out about the terrible past of her seemingly ideal husband, while simultaneously learning of her own cancer diagnosis, she begins an awakening from the suburban paradise she has been living in. Cast: Mirjana Karanovic, Boris Isakovic, Jasna Djuricic, Bojan Navojec, Hristina Popovic, Ksenija Marinkovic.

HALAL LOVE (AND SEX) (Lebanon-Germany-United Arab Emirates / Director and screenwriter: Assad Fouladkar) — Four tragic yet comic interconnected stories come together in this film, which follows devout Muslim men and women as they try to manage their love lives and desires without breaking any of their religion’s rules. Cast: Darine Hamze, Rodrigue Sleiman, Zeinab Khadra, Hussein Mokadem, Mirna Moukarzel, Ali Sammoury. (International premiere)

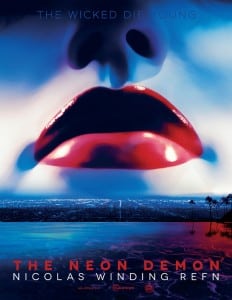

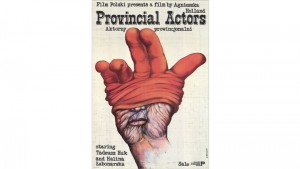

THE LURE (main photo) (Poland / Director: Agnieszka Smoczynska, Screenwriter: Robert Bolesto) — Two mermaid sisters, who end up performing at a nightclub, face cruel and bloody choices when one of them falls in love with a beautiful young man. Cast: Marta Mazurek, Michalina Olszanska, Jakub Gierszal, Kinga Preis, Andrzej Konopka, Zygmunt Malanowicz. (International premiere)

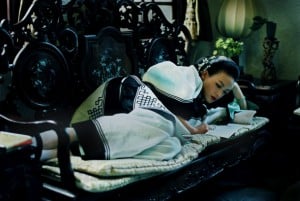

MALE JOY, FEMALE LOVE right (China / Director and screenwriter: Yao Huang) — Portrays an unlimited cycle of love stories. Cast: Nand Yu, Daizhen Ying, Xiaodong Guo, Yi Sun.

MALE JOY, FEMALE LOVE right (China / Director and screenwriter: Yao Huang) — Portrays an unlimited cycle of love stories. Cast: Nand Yu, Daizhen Ying, Xiaodong Guo, Yi Sun.

MAMMAL (Ireland-Luxembourg-Netherlands / Director: Rebecca Daly, Screenwriters: Rebecca Daly, Glenn Montgomery) — After Margaret, a divorcee living in Dublin, loses her teenage son, she develops an unorthodox relationship with Joe, a homeless youth. Their tentative trust is threatened by his involvement with a violent gang and the escalation of her exhusband’s grieving rage. Cast: Rachel Griffiths, Barry Keoghan, Michael McElhatton.

MI AMIGA DEL PARQUE (Argentina-Uruguay / Director: Ana Katz, Screenwriters: Ana Katz, Ines Bortagaray) — Running away from a bar without paying the bill is just the first adventure for Liz (mother to newborn Nicanor) and Rosa (supposed mother to newborn Clarisa). This budding friendship between nursing mothers starts with the promise of liberation but soon ends up being a dangerous business. Cast: Julieta Zylberberg, Ana Katz, Maricel Alvarez, Mirella Pascual, Malena Figo, Daniel Hendler. (International premiere)

MI AMIGA DEL PARQUE (Argentina-Uruguay / Director: Ana Katz, Screenwriters: Ana Katz, Ines Bortagaray) — Running away from a bar without paying the bill is just the first adventure for Liz (mother to newborn Nicanor) and Rosa (supposed mother to newborn Clarisa). This budding friendship between nursing mothers starts with the promise of liberation but soon ends up being a dangerous business. Cast: Julieta Zylberberg, Ana Katz, Maricel Alvarez, Mirella Pascual, Malena Figo, Daniel Hendler. (International premiere)

MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING (Chile / Director: Alejandro Fernandez, Screenwriters: Alejandro Fernandez, Jeronimo Rodriguez) — An upper-class kid gets in trouble with the one percent. Cast: Agustin Silva, Alejandro Goic, Luis Gnecco, Paulina Garcia, Daniel Alcaino, Augusto Schuster.

SAND STORM (Israel / Director and screenwriter: Elite Zexer) — When their entire lives are shattered, two Bedouin women struggle to change the unchangeable rules, each in her own individual way. Cast: Lamis Ammar, Ruba BlalAsfour, Hitham Omari, Khadija Alakel, Jalal Masrwa.

WILD (Germany / Director and screenwriter: Nicolette Krebitz) — An anarchist young woman breaks the tacit contract with civilization and fearlessly decides on a life without hypocrisy or an obligatory safety net. Cast: Lilith Stangenberg, Georg Friedrich.

WORLD CINEMA DOCUMENTARY COMPETITION

The 11 films in this section are world premieres unless otherwise specified. A 12th film will be announced in the weeks ahead.

The 11 films in this section are world premieres unless otherwise specified. A 12th film will be announced in the weeks ahead.

ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS (LEFT) (Poland / Director: Michal Marczak) — What does it mean to be truly awake in a world that seems satisfied to be asleep? Christopher and Michal push their experiences in life and love to the breaking point as they restlessly roam the streets of Warsaw in search for answers.

A FLAG WITHOUT A COUNTRY (Iraq / Director: Bahman Ghobadi) — This documentary follows the very separate paths of singer Helly Luv and pilot Nariman Anwar from Kurdistan, both in pursuit of progress, freedom, and solidarity. Both individuals are a source of strength to their society, which perpetually deals with the harsh conditions of life, war, and ISIS attacks. (North American premiere)

HOOLIGAN SPARROW – right (China-U.S. / Director: Nanfu Wang) — Traversing southern China, a group of activists led by Ye Haiyan, aka Hooligan Sparrow, protest a scandalous incident in which a school principal and a government official allegedly raped six students. Sparrow becomes an enemy of the state, but detentions, interrogations and evictions can’t stop her protest from going viral.

HOOLIGAN SPARROW – right (China-U.S. / Director: Nanfu Wang) — Traversing southern China, a group of activists led by Ye Haiyan, aka Hooligan Sparrow, protest a scandalous incident in which a school principal and a government official allegedly raped six students. Sparrow becomes an enemy of the state, but detentions, interrogations and evictions can’t stop her protest from going viral.

THE LAND OF THE ENLIGHTENED (Belgium / Director: Pieter-Jan De Pue) — A group of Kuchi children in Afghanistan dig out old Soviet mines and sell the explosives to child workers in a lapis lazuli mine. When not dreaming of an Afghanistan after the American withdrawal, Gholam Nasir and his gang control the mountains where caravans are smuggling the blue gemstones.

THE LOVERS AND THE DESPOT (U.K. / Directors: Robert Cannan, Ross Adam) — Following the collapse of their glamorous romance, a celebrity director and his actress ex-wife are kidnapped by movie-obsessed dictator Kim Jong-il. Forced to make films in extraordinary circumstances, they get a second chance at love — but only one chance at escape.

PLAZA DE LA SOLEDAD (Mexico / Director: Maya Goded) — For more than 20 years, photographer Maya Goded has intimately documented the lives of a close community of prostitutes in Mexico City. With dignity and humor, these women now strive for a better life — and the possibility of true love.

THE SETTLERS (France-Canada-Israel-Germany / Director: Shimon Dotan) — The first film of its kind to offer a comprehensive view of the Jewish settlements in the West Bank, “The Settlers” is a historical overview, geopolitical study, and intimate look at the people at the core of the most daunting challenge facing Israel and the international community today.

SKY LADDER: The Art of Cai Guo-Qiang” (Director: Kevin Macdonald) — Having reached the pinnacle of the global art world with his signature explosion events and gunpowder drawings, world-famous Chinese contemporary artist Cai Guo-Qiang is still seeking more. We trace his rise from childhood in Mao’s China and his journey to attempt to realize his lifelong obsession, Sky Ladder. (Day One film)

SKY LADDER: The Art of Cai Guo-Qiang” (Director: Kevin Macdonald) — Having reached the pinnacle of the global art world with his signature explosion events and gunpowder drawings, world-famous Chinese contemporary artist Cai Guo-Qiang is still seeking more. We trace his rise from childhood in Mao’s China and his journey to attempt to realize his lifelong obsession, Sky Ladder. (Day One film)

SONITA (Germany-Iran-Switzerland / Director: Rokhsareh Ghaem Maghami) — If 18yearold Sonita had a say, Michael Jackson and Rihanna would be her parents and she’d be a rapper who tells the story of Afghan women and their fate as child brides. She finds out that her family plans to sell her to an unknown husband for $9,000. (North American premiere)

WE ARE X / (U.K.-U.S.-Japan / Director: Stephen Kijak) — As glam rock’s most flamboyant survivors, X Japan ignited a musical revolution in Japan during the late ’80s with their melodic metal. Twenty years after their tragic dissolution, X Japan’s leader, Yoshiki, battles with physical and spiritual demons alongside prejudices of the West to bring their music to the world.

WHEN TWO WORLDS COLLIDE right (Peru / Directors: Heidi Brandenburg, Mathew Orzel) — An indigenous leader resists the environmental ruin of Amazonian lands by big business. As he is forced into exile and faces 20 years in prison, his quest reveals conflicting visions that shape the fate of the Amazon and the climate future of our world. World Premiere

WHEN TWO WORLDS COLLIDE right (Peru / Directors: Heidi Brandenburg, Mathew Orzel) — An indigenous leader resists the environmental ruin of Amazonian lands by big business. As he is forced into exile and faces 20 years in prison, his quest reveals conflicting visions that shape the fate of the Amazon and the climate future of our world. World Premiere

SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL | UTAH 21 – 31 JANUARY 2015 |

Dresden 1918, Robert Siodmak left his upper-middle class, orthodox Jewish home in this epicentre of European modern art, to join a theatre touring company. He was 18, and this was the first of many radical changes that would see him becoming a pioneer of film noir, and directing 56 feature films fraught with (anti)heroes who are morose, malevolent, violent and generally downbeat (spoilers).

Dresden 1918, Robert Siodmak left his upper-middle class, orthodox Jewish home in this epicentre of European modern art, to join a theatre touring company. He was 18, and this was the first of many radical changes that would see him becoming a pioneer of film noir, and directing 56 feature films fraught with (anti)heroes who are morose, malevolent, violent and generally downbeat (spoilers).

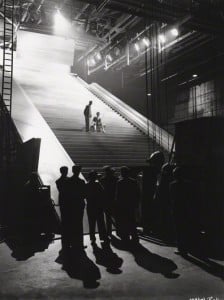

Films don’t always end up the way their makers originally envisaged at their outset, and the maiden production of Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger’s Archers Films would have turned out completely differently had Laurence Olivier been freed from the Fleet Air Arm to make it; since it is now impossible to imagine without third-billed Roger Livesey and his distinctive voice in the title role (in which at the age of 36 he convincingly ages forty years). The makers’ relative inexperience shows in the fact that they ended up with a initial cut over two and a half hours long; but fortunately J.Arthur Rank liked the film so much he let it hit cinemas as it was. Indeed, it was Pressburger’s favourite of the Rank outings, and would go on to influence the work of future filmmakers such as Scorsese in his The Age of Innocence and Tarantino who copied the device of beginning and ending a film be rerunning the same scene from the point of view of different characters.

Films don’t always end up the way their makers originally envisaged at their outset, and the maiden production of Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger’s Archers Films would have turned out completely differently had Laurence Olivier been freed from the Fleet Air Arm to make it; since it is now impossible to imagine without third-billed Roger Livesey and his distinctive voice in the title role (in which at the age of 36 he convincingly ages forty years). The makers’ relative inexperience shows in the fact that they ended up with a initial cut over two and a half hours long; but fortunately J.Arthur Rank liked the film so much he let it hit cinemas as it was. Indeed, it was Pressburger’s favourite of the Rank outings, and would go on to influence the work of future filmmakers such as Scorsese in his The Age of Innocence and Tarantino who copied the device of beginning and ending a film be rerunning the same scene from the point of view of different characters.

LE CORBEAU (1942)

LE CORBEAU (1942)

L

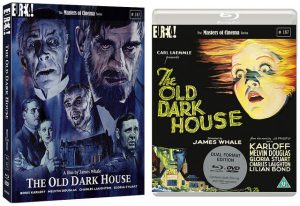

L Dir: James Whale | Wri: Benn Levy/J B Priestley | Cast: Boris Karloff| Charles Laughton | Eva Moore | Gloria Stuart | Melvyn Douglas| Raymond Massey | Horror / Comedy |US 75′

Dir: James Whale | Wri: Benn Levy/J B Priestley | Cast: Boris Karloff| Charles Laughton | Eva Moore | Gloria Stuart | Melvyn Douglas| Raymond Massey | Horror / Comedy |US 75′ Catherine the Great

Catherine the Great Dir|Wri: Nicolás Rincón Gille | Doc 136′ | Columbia, Belgium

Dir|Wri: Nicolás Rincón Gille | Doc 136′ | Columbia, Belgium

Marrakech Film Festival is one of the most glamorous events in the film festival circuit attracting professionals and film lovers from all over the World and honouring global film in all its forms. This year’s International Competition Jury is headed by Tilda Swinton, who has starred in over 70 feature films, most recently in The Personal History of David Copperfield, and Wes Anderson latest comedy drama The French Dispatch which will premiere early next year.

Marrakech Film Festival is one of the most glamorous events in the film festival circuit attracting professionals and film lovers from all over the World and honouring global film in all its forms. This year’s International Competition Jury is headed by Tilda Swinton, who has starred in over 70 feature films, most recently in The Personal History of David Copperfield, and Wes Anderson latest comedy drama The French Dispatch which will premiere early next year. Woman’s Day

Woman’s Day Irina Zhuravleva and Vladislav Grishin have developed a meditative approach to studying the lives of bears in the South Kamchatka Federal Sanctuary. In Kamchatka Bears: Life Begins, music, ambient sounds and the absence of a human voices makes this a chance to experience nature at its purest form.

Irina Zhuravleva and Vladislav Grishin have developed a meditative approach to studying the lives of bears in the South Kamchatka Federal Sanctuary. In Kamchatka Bears: Life Begins, music, ambient sounds and the absence of a human voices makes this a chance to experience nature at its purest form. Great Poetry is a portrait of loneliness, friendship and betrayal that sees two men clinging together for survival as cash collectors in the outskirts of Moscow where their time is spent moving money for other people and gaming on cockfights at a dorm of migrant workers. Dreaming of a better future, they enrol on a poetry class but sadly find it easier to make a living as petty criminals in this wistful reflection on 19th ideals. Aleksandr Kutznetsov was awarded Best Actor or his performance in the film that also won Lungin Best Director at this year’s Sochi Russian Open Film Festival

Great Poetry is a portrait of loneliness, friendship and betrayal that sees two men clinging together for survival as cash collectors in the outskirts of Moscow where their time is spent moving money for other people and gaming on cockfights at a dorm of migrant workers. Dreaming of a better future, they enrol on a poetry class but sadly find it easier to make a living as petty criminals in this wistful reflection on 19th ideals. Aleksandr Kutznetsov was awarded Best Actor or his performance in the film that also won Lungin Best Director at this year’s Sochi Russian Open Film Festival Alexander Zolotukhin’s elegiac portrait of a young Russian soldier pieces together the early days of the The First World War when tragedy strikes even before glory is allowed to show its face. Three decades later, at the beginning of the Second World War, Rachmaninoff will create “Symphonic dances” op.45, an even more grand and vigorous work which was also his swansong. A tender tragedy suffused with courage and melancholy.

Alexander Zolotukhin’s elegiac portrait of a young Russian soldier pieces together the early days of the The First World War when tragedy strikes even before glory is allowed to show its face. Three decades later, at the beginning of the Second World War, Rachmaninoff will create “Symphonic dances” op.45, an even more grand and vigorous work which was also his swansong. A tender tragedy suffused with courage and melancholy. Dir Miloš Forman | Cast: John Savage, Treat Williams, Beverly D’Angelo, Annie Golden | US Comedy musical 121′

Dir Miloš Forman | Cast: John Savage, Treat Williams, Beverly D’Angelo, Annie Golden | US Comedy musical 121′ LA DONA DEL SEGLE | The Woman of the Century

LA DONA DEL SEGLE | The Woman of the Century Dir: Roman Polanski | Wri: Robert Harris | 122’

Dir: Roman Polanski | Wri: Robert Harris | 122’ Losey’s adaptation of LP Hartley’s novel is arguably his masterpiece. Pinter’s script adds a darkly amusing twist to the torrid love and coming of age story set in the lush summer landscapes of Norfolk to Michel Legrand’s iconic score.

Losey’s adaptation of LP Hartley’s novel is arguably his masterpiece. Pinter’s script adds a darkly amusing twist to the torrid love and coming of age story set in the lush summer landscapes of Norfolk to Michel Legrand’s iconic score. Elsewhere in the programme, Sasha Collington’s

Elsewhere in the programme, Sasha Collington’s

MARIE-LOUISE IRIBE Parisian actress and filmmaker, Marie Louise Iribe (1894-1934) had a short but dazzling career and is best known for her 1928 debut Hara-Kiri (co-directed with Henri Debain). Her follow-up Le Roi de Aulnes (1931) is based on a poem by Goethe. This enchanting filigree fairy tale has the same magical touch and look as Cocteau’s La Belle et la Bête which followed 15 years later and during wartime. The simple but moving storyline sees a man riding through hill and dale to carry his injured son home. As he slips in an out of consciousness the boy imagines death as a mythical king surrounded by wood nymphs. Emile Pierre delicately overlays the forest journey with ethereal images of the king in iridescent armour, transformed from a humble toad realised by DoP Emilie Pierre’s ethereal double exposures. Max D’Ollone’s atmospheric score brings the magic to life.

MARIE-LOUISE IRIBE Parisian actress and filmmaker, Marie Louise Iribe (1894-1934) had a short but dazzling career and is best known for her 1928 debut Hara-Kiri (co-directed with Henri Debain). Her follow-up Le Roi de Aulnes (1931) is based on a poem by Goethe. This enchanting filigree fairy tale has the same magical touch and look as Cocteau’s La Belle et la Bête which followed 15 years later and during wartime. The simple but moving storyline sees a man riding through hill and dale to carry his injured son home. As he slips in an out of consciousness the boy imagines death as a mythical king surrounded by wood nymphs. Emile Pierre delicately overlays the forest journey with ethereal images of the king in iridescent armour, transformed from a humble toad realised by DoP Emilie Pierre’s ethereal double exposures. Max D’Ollone’s atmospheric score brings the magic to life.

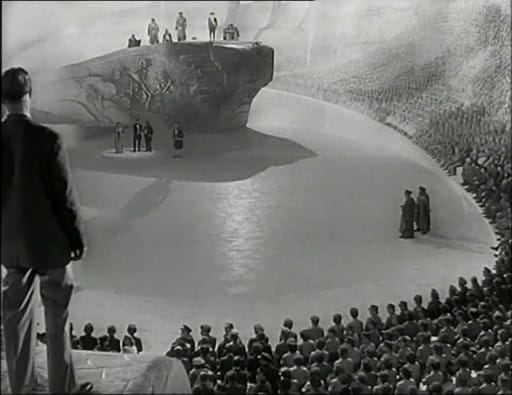

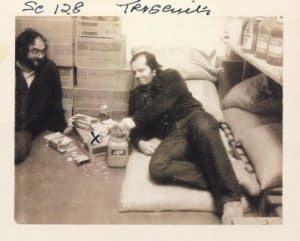

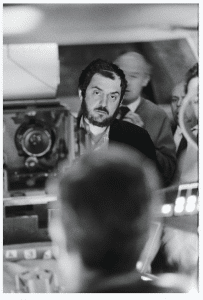

Stanley Kubrick, one of the greatest film makers of the 20th century, spent most of his later life working in England where he raised a family in the Hertfordshire town of Childwickbury, between St Albans and Harpenden, 35 minutes drive North of London. It was in the Norfolk Broads and Beckton, in the East End that he created the Vietnam scenes for Full Metal Jacket (1987), an orbiting space station for 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), and Dr Strangelove’s war room (1964).

Stanley Kubrick, one of the greatest film makers of the 20th century, spent most of his later life working in England where he raised a family in the Hertfordshire town of Childwickbury, between St Albans and Harpenden, 35 minutes drive North of London. It was in the Norfolk Broads and Beckton, in the East End that he created the Vietnam scenes for Full Metal Jacket (1987), an orbiting space station for 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), and Dr Strangelove’s war room (1964). Stanley Kubrick was most inventive in his introduction of revolutionary devices to his filmmaking, such as the camera lens designed for NASA to shoot by candlelight. His fascination with all aspects of design and architecture influenced every stage of all his films. He worked with many key designers of his generation, from Hardy Amies to Saul Bass, Eliot Noyes and Ken Adam.

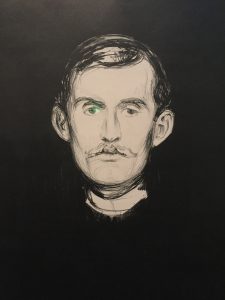

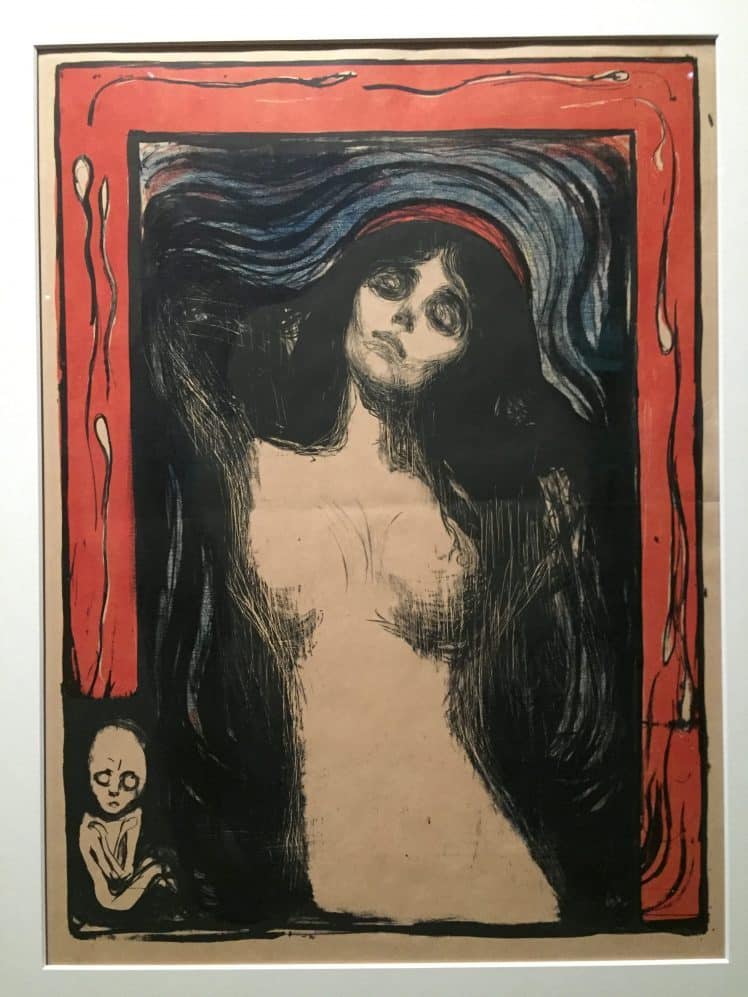

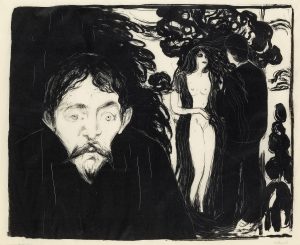

Stanley Kubrick was most inventive in his introduction of revolutionary devices to his filmmaking, such as the camera lens designed for NASA to shoot by candlelight. His fascination with all aspects of design and architecture influenced every stage of all his films. He worked with many key designers of his generation, from Hardy Amies to Saul Bass, Eliot Noyes and Ken Adam. Edvard Munch (1863-1944) was a famous pioneer of modern art, best known for his iconic image of The Scream. His idiosyncratic expression of raw human emotion reflects many of the anxieties and hotly debated issues of his times, yet his art still still resonates today.

Edvard Munch (1863-1944) was a famous pioneer of modern art, best known for his iconic image of The Scream. His idiosyncratic expression of raw human emotion reflects many of the anxieties and hotly debated issues of his times, yet his art still still resonates today.

During his life Munch spent much time in Paris and Berlin where in 1892, he was invited to exhibit his paintings in the recently formed German Empire. Berlin was Europe’s industrial boom city, ruled over the ambitious Kaiser Bill (Wilhelm II). Grand avenues gave the impression of military order but bohemian undercurrents ran just below the surface, alongside Europe’s strongest workers’ movement. His exhibition horrified the traditional art world, but was much admired by the Avantgarde with the scandal helping him to launch his international career.

During his life Munch spent much time in Paris and Berlin where in 1892, he was invited to exhibit his paintings in the recently formed German Empire. Berlin was Europe’s industrial boom city, ruled over the ambitious Kaiser Bill (Wilhelm II). Grand avenues gave the impression of military order but bohemian undercurrents ran just below the surface, alongside Europe’s strongest workers’ movement. His exhibition horrified the traditional art world, but was much admired by the Avantgarde with the scandal helping him to launch his international career. Dir: Mike Slee | Carl Knutson, Wendy MacKeigan | Cast: Calum Finlay, Ed Birch, Billy Postlethwaite, Robert Daws, Louis Partridge | Docudrama 46′

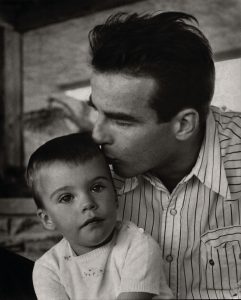

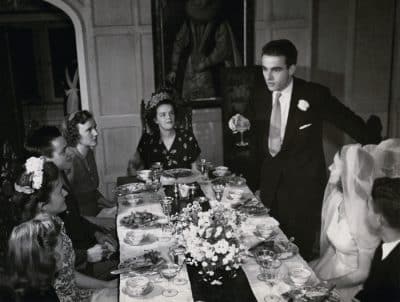

Dir: Mike Slee | Carl Knutson, Wendy MacKeigan | Cast: Calum Finlay, Ed Birch, Billy Postlethwaite, Robert Daws, Louis Partridge | Docudrama 46′ Co-directing and narrating this eye-opening documentary, Robert Clift (who never knew Monty) digs into a treasure trove of family archives and memorabilia (Brooks recorded everything) to reveal an affectionate, fun-loving talent who loved men and dated and lived with women, according to close friends. Monty chose his roles carefully during the ’40s and ’50s, declining to sign a contract to retain complete artistic independence from the studio system with the ability to pick and chose, and re-write his dialogue. This freedom also enabled him to keep much of his private life out of the headlines, although his memory was eventually sullied by tabloid melodrama with his untimely death at only 45. His acting ability and dazzling looks certainly gained him a place in the Hollywood firmament with a select filmography of just 20 features, four of them Oscar-nominated.

Co-directing and narrating this eye-opening documentary, Robert Clift (who never knew Monty) digs into a treasure trove of family archives and memorabilia (Brooks recorded everything) to reveal an affectionate, fun-loving talent who loved men and dated and lived with women, according to close friends. Monty chose his roles carefully during the ’40s and ’50s, declining to sign a contract to retain complete artistic independence from the studio system with the ability to pick and chose, and re-write his dialogue. This freedom also enabled him to keep much of his private life out of the headlines, although his memory was eventually sullied by tabloid melodrama with his untimely death at only 45. His acting ability and dazzling looks certainly gained him a place in the Hollywood firmament with a select filmography of just 20 features, four of them Oscar-nominated. Particularly interesting are Brooks’ conversations with Patricia Bosworth, one of the film’s talking heads and the author of a 1978 biography of Clift that inspired later biographies, but has so far become the accepted version of events, although she apparently got many details wrong and certainly lost out to Jenny Balaban in the Monty relationship stakes, when Barney Balaban (President of Paramount) invited the young actor to join them on a family holiday. He is seen messing around on the beach where he cuts a dash with his good looks and exuberance.

Particularly interesting are Brooks’ conversations with Patricia Bosworth, one of the film’s talking heads and the author of a 1978 biography of Clift that inspired later biographies, but has so far become the accepted version of events, although she apparently got many details wrong and certainly lost out to Jenny Balaban in the Monty relationship stakes, when Barney Balaban (President of Paramount) invited the young actor to join them on a family holiday. He is seen messing around on the beach where he cuts a dash with his good looks and exuberance. Dir: Alain Resnais; Cast: Sabine Azéma, Pierre Arditi, André Dussollier, Fanny Ardant; France 1986, 112 min.

Dir: Alain Resnais; Cast: Sabine Azéma, Pierre Arditi, André Dussollier, Fanny Ardant; France 1986, 112 min. Turkish cinema is known for its captivating widescreen dramas that reflect the cultural diversity and magnificent scenery of a vibrant nation that stretches from Europe to Asia.

Turkish cinema is known for its captivating widescreen dramas that reflect the cultural diversity and magnificent scenery of a vibrant nation that stretches from Europe to Asia. The Golden Tulip winner 2017 YELLOW HEAT (Sari Sicak) sees an immigrant family desperate to survive in their traditional farm amid encroaching industrialisation. The multi-award winning drama YOZGAT BLUES (2013), set in small town Anatolia, is one to watch for its outstanding performances and smouldering cinematography. Banu Sivaci’s THE PIGEON (main image) won best director at Sofia Film Festival 2018 and is another impressive arthouse tale of a boy finding peace with the animal kingdom, away from the dystopian world in small-town Adana, Southern Turkey. And finally MURTAZA another beautifully crafted and resonant parable about the importance of traditional values in the mountains of Malatya.

The Golden Tulip winner 2017 YELLOW HEAT (Sari Sicak) sees an immigrant family desperate to survive in their traditional farm amid encroaching industrialisation. The multi-award winning drama YOZGAT BLUES (2013), set in small town Anatolia, is one to watch for its outstanding performances and smouldering cinematography. Banu Sivaci’s THE PIGEON (main image) won best director at Sofia Film Festival 2018 and is another impressive arthouse tale of a boy finding peace with the animal kingdom, away from the dystopian world in small-town Adana, Southern Turkey. And finally MURTAZA another beautifully crafted and resonant parable about the importance of traditional values in the mountains of Malatya. Other features and shorts reflect the usual Turkish themes of town versus country, tradition versus the modern world, and the role of women in enlightened society. Another highlight will be Ahmet Boyacioglu’s latest film THE SMELL OF MONEY a tense and startling exposé of financial corruption in contemporary Turkey. And last but not least, a panel of industry professionals will debate the future of the big screen At the Flicks of Netflix? at the Regent Street Cinema on 26th April.

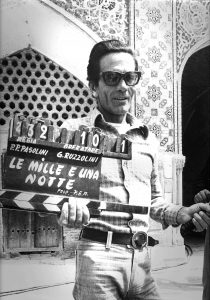

Other features and shorts reflect the usual Turkish themes of town versus country, tradition versus the modern world, and the role of women in enlightened society. Another highlight will be Ahmet Boyacioglu’s latest film THE SMELL OF MONEY a tense and startling exposé of financial corruption in contemporary Turkey. And last but not least, a panel of industry professionals will debate the future of the big screen At the Flicks of Netflix? at the Regent Street Cinema on 26th April. PASOLINI AND THE ARABIAN NIGHTS

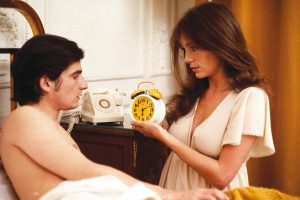

PASOLINI AND THE ARABIAN NIGHTS In 1966 Léaud would star in Godard’s Masculin, feminin: 15 Faits Précis, winning a Silver Bear for Best Actor at the Berlinale for his role as Paul, who is in a ménage-a-quatre with three women in a contemporary Paris. Loosely based on Maupassant’s short stories, this feature was the beginning of the break Godard would make with narrative cinema. Also called The Children of Marx and Coca Cola (an inter-title of the feature), sex and politics are at the core. Léaud is fragile, and the lighting shows him as beautiful and vulnerable as the three women, Madeleine (Chantal Goya), Catherine (Isabelle Duport) and Elisabeth (Marlene Jobert). All four main protagonists have very different plans for the future, when their agendas collide. There is immense elegance and beauty here (DoP Willy Kurant), and Godard treats his actors (perhaps for the last time) with more care than in the verbal politics of later films. Pauline Kael called it “that rare achievement: a work of grace in a contemporary setting” and for Andrew Sarris it was “the film of the season”.

In 1966 Léaud would star in Godard’s Masculin, feminin: 15 Faits Précis, winning a Silver Bear for Best Actor at the Berlinale for his role as Paul, who is in a ménage-a-quatre with three women in a contemporary Paris. Loosely based on Maupassant’s short stories, this feature was the beginning of the break Godard would make with narrative cinema. Also called The Children of Marx and Coca Cola (an inter-title of the feature), sex and politics are at the core. Léaud is fragile, and the lighting shows him as beautiful and vulnerable as the three women, Madeleine (Chantal Goya), Catherine (Isabelle Duport) and Elisabeth (Marlene Jobert). All four main protagonists have very different plans for the future, when their agendas collide. There is immense elegance and beauty here (DoP Willy Kurant), and Godard treats his actors (perhaps for the last time) with more care than in the verbal politics of later films. Pauline Kael called it “that rare achievement: a work of grace in a contemporary setting” and for Andrew Sarris it was “the film of the season”. A year later Godard would cast Léaud as part of a group in La Chinoise (1967), this time surrounded by two women and two men, but with a very much harsher political focus. Based on Dostoyevsky’s The Possessed, this was Godard’s first adventure into Maoism. Léaud is Guillaume, in love with Veronique (Anne Wiazemsky), who has a much stronger personality than him, and will finally leave him. Kirilov (Lex de Bruijin), is the weakest of the trio and he will kill himself, as in the novel. Léaud’s Guillaume is in love with Veronique, but he is very much a man of clever words, but little action. Veronique on the other hand, is much braver, and decides in the end to assassinate the Russian Cultural minister on a visit to Paris. But he mixes up the numbers of his hotel room, and kills the wrong man. Wiazemsky, the grand daughter of novelist Andrew Malraux, then the Gaullist minister for Culture, fell in love with Godard, and the couple married after the shooting. As an in-joke, Godard casts Francis Jeanson in the film (Wiazemsky’s philosophy lecturer at the Paris 10 (Nanterre) University) having a debate with Veronique while on her way to assassinate the minister.

A year later Godard would cast Léaud as part of a group in La Chinoise (1967), this time surrounded by two women and two men, but with a very much harsher political focus. Based on Dostoyevsky’s The Possessed, this was Godard’s first adventure into Maoism. Léaud is Guillaume, in love with Veronique (Anne Wiazemsky), who has a much stronger personality than him, and will finally leave him. Kirilov (Lex de Bruijin), is the weakest of the trio and he will kill himself, as in the novel. Léaud’s Guillaume is in love with Veronique, but he is very much a man of clever words, but little action. Veronique on the other hand, is much braver, and decides in the end to assassinate the Russian Cultural minister on a visit to Paris. But he mixes up the numbers of his hotel room, and kills the wrong man. Wiazemsky, the grand daughter of novelist Andrew Malraux, then the Gaullist minister for Culture, fell in love with Godard, and the couple married after the shooting. As an in-joke, Godard casts Francis Jeanson in the film (Wiazemsky’s philosophy lecturer at the Paris 10 (Nanterre) University) having a debate with Veronique while on her way to assassinate the minister. Truffaut’s 1973 outing La Nuit Americaine (Day for Night), is essentially about filmmaking, showing Léaud as the weak and self-obsessed actor Alphonse. During the filming of Je vous présente Pamela , a conventional weepie, he fancies leading lady Julie Baker (Jacqueline Bisset), who has recently had a breakdown. Out of pity she sleeps with him but Alphonse then ‘phones her analyst, Dr Nelson (David Markham), who has left his own family to live with her, and spills the beans on their fling. Léaud plays the histrionic weakling with great skill. And Truffaut, playing himself as the director, assumes the role of his protector – much as in real life. Godard, who by now had broken with his ex-friend Truffaut, called Day for Night “a big lie” – later the two founding fathers of the Nouvelle Vague fought over Léaud who somehow survived the acrimony and went on to work with another enfant terrible, Finnish director Aki Kaurismaki.

Truffaut’s 1973 outing La Nuit Americaine (Day for Night), is essentially about filmmaking, showing Léaud as the weak and self-obsessed actor Alphonse. During the filming of Je vous présente Pamela , a conventional weepie, he fancies leading lady Julie Baker (Jacqueline Bisset), who has recently had a breakdown. Out of pity she sleeps with him but Alphonse then ‘phones her analyst, Dr Nelson (David Markham), who has left his own family to live with her, and spills the beans on their fling. Léaud plays the histrionic weakling with great skill. And Truffaut, playing himself as the director, assumes the role of his protector – much as in real life. Godard, who by now had broken with his ex-friend Truffaut, called Day for Night “a big lie” – later the two founding fathers of the Nouvelle Vague fought over Léaud who somehow survived the acrimony and went on to work with another enfant terrible, Finnish director Aki Kaurismaki. I hired a Contract Killer (1990) was one of Kaurismaki’s first English language films and he made a beeline for Léaud in the lead role. The gamine actor of Day for Night had since changed dramatically. His slight, almost feminine appearance was gone, and he’d put on a substantial amount of weight – his acting too was from another dimension. He plays Henri Boulanger, an English Civil Servant, who is sacked after fifteen years of service due to privatisation. With no life outside his work, he tries – in vain – to commit suicide. Then asks a contract killer (Kenneth Colley) to step in. But Margaret (Margi Clarke) gives his life a new meaning. With time running out, Henri tries to contact the killer, to reverse the order. Léaud is totally morbid and emotionally reduced, the environment is straight out of the 1950s, the colours pale, bleached out by wear and tear. Léaud’s agile friskiness has been replaced by gentle placidness, making him look much older than forty-six. But his acting had matured too, and he slips easily into character roles nobody would have expected from him in his New Wave days. AS

I hired a Contract Killer (1990) was one of Kaurismaki’s first English language films and he made a beeline for Léaud in the lead role. The gamine actor of Day for Night had since changed dramatically. His slight, almost feminine appearance was gone, and he’d put on a substantial amount of weight – his acting too was from another dimension. He plays Henri Boulanger, an English Civil Servant, who is sacked after fifteen years of service due to privatisation. With no life outside his work, he tries – in vain – to commit suicide. Then asks a contract killer (Kenneth Colley) to step in. But Margaret (Margi Clarke) gives his life a new meaning. With time running out, Henri tries to contact the killer, to reverse the order. Léaud is totally morbid and emotionally reduced, the environment is straight out of the 1950s, the colours pale, bleached out by wear and tear. Léaud’s agile friskiness has been replaced by gentle placidness, making him look much older than forty-six. But his acting had matured too, and he slips easily into character roles nobody would have expected from him in his New Wave days. AS

THE GUEST (L’Ospite) ****

THE GUEST (L’Ospite) ****

This year’s Rotterdam Film Festival takes place from 23 January until the 3rd February with the latest World premieres running alongside 4 sections entitled Bright Future, Voices, Deep Focus and Perspectives – and a cutting-edge arts programme to add a cultural dimension to the 10 days, and this year includes SLEEPCINEMAHOTEL a one off project by Apichatpong Weerasethakul, and never before seen outtakes from Sergei Parajanov’s masterpiece The Colour of Pomegranates (196

This year’s Rotterdam Film Festival takes place from 23 January until the 3rd February with the latest World premieres running alongside 4 sections entitled Bright Future, Voices, Deep Focus and Perspectives – and a cutting-edge arts programme to add a cultural dimension to the 10 days, and this year includes SLEEPCINEMAHOTEL a one off project by Apichatpong Weerasethakul, and never before seen outtakes from Sergei Parajanov’s masterpiece The Colour of Pomegranates (196 T I G E R C O M P E T I T I O N

T I G E R C O M P E T I T I O N

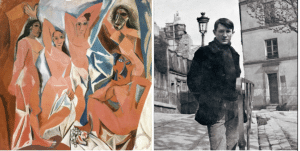

The Young Picasso

The Young Picasso

Dir.: Frank Capra; Cast: James Stewart, Donna Reed, Lionel Barrymore, Henry Travers; USA 1946; 130 min.

Dir.: Frank Capra; Cast: James Stewart, Donna Reed, Lionel Barrymore, Henry Travers; USA 1946; 130 min. We spoke to Competition Jury member Lynne Ramsay to talk about her latest project and the film that most impressed her as a child growing up in Glasgow.

We spoke to Competition Jury member Lynne Ramsay to talk about her latest project and the film that most impressed her as a child growing up in Glasgow. Dir: Tony Richardson | Writers: Shelagh Delaney, Tony Richardson | Cast: Rita Tushingham, Murray Melvin, Dora Bryan, John Danquah, Robert Stephens | UK | Drama | 101′

Dir: Tony Richardson | Writers: Shelagh Delaney, Tony Richardson | Cast: Rita Tushingham, Murray Melvin, Dora Bryan, John Danquah, Robert Stephens | UK | Drama | 101′

Agnes Varda (b.1928 Belgium)

Agnes Varda (b.1928 Belgium)  Robert De Niro. (b. 1943, US)

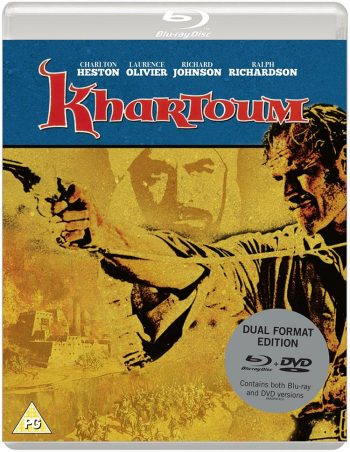

Robert De Niro. (b. 1943, US) KHARTOUM is the kind of spectacular, rousing historical adventure that doesn’t get made anymore, certainly not along the same lines as Basil Dearden’s star-studded epic that exposes English colonialism, religious fanaticism, heroism and sacrifice in a magnificent visual masterpiece. Back in the day, it all seemed perfectly harmless to our innocent childhood eyes as we sat round the telly oblivious to the political incorrectness. And that wasn’t the worst thing: it later emerged that over a hundred horses were severely injured or killed immediately during the battle scenes, due to unethical stunt methods of the time.

KHARTOUM is the kind of spectacular, rousing historical adventure that doesn’t get made anymore, certainly not along the same lines as Basil Dearden’s star-studded epic that exposes English colonialism, religious fanaticism, heroism and sacrifice in a magnificent visual masterpiece. Back in the day, it all seemed perfectly harmless to our innocent childhood eyes as we sat round the telly oblivious to the political incorrectness. And that wasn’t the worst thing: it later emerged that over a hundred horses were severely injured or killed immediately during the battle scenes, due to unethical stunt methods of the time. John Schlesinger’s YANKS, a moving and romantic WWII tale of love starring Richard Gere and Vanessa Redgrave is based on Lancashire born Colin Welland’s original story, he also wrote the script.

John Schlesinger’s YANKS, a moving and romantic WWII tale of love starring Richard Gere and Vanessa Redgrave is based on Lancashire born Colin Welland’s original story, he also wrote the script.

Dir.: Aleksey Fedorchenko; Cast: Marta Kozlava; Russia 2018, 74 min.

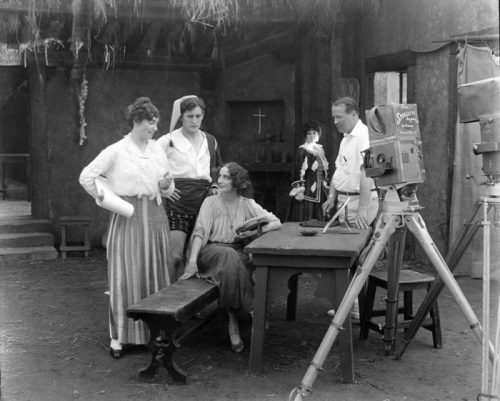

Dir.: Aleksey Fedorchenko; Cast: Marta Kozlava; Russia 2018, 74 min. Mabel Normand (1892-1930) had a short but eventful life: she was a pioneer of Silent Movies as a star actress (in 220) and director (in 10) between 1910 and 1927. Working alongside Charlie Chaplin, she ended up saving his career at Mack Sennetts’ Keystone – the producer wanted to sack him. Normand also developed Chaplin’s ‘tramp’ screen personality. But she was, more or less, accidentally involved in the murder of William Desmond Taylor and the shooting of Courtland S. Dines, as well as being a friend (and co-star) of ‘Fatty’ Arbuckle, whose life was a series of scandals. Normand suffered for a long time from TB, interrupting her career and leading to her early death at the age of 37.

Mabel Normand (1892-1930) had a short but eventful life: she was a pioneer of Silent Movies as a star actress (in 220) and director (in 10) between 1910 and 1927. Working alongside Charlie Chaplin, she ended up saving his career at Mack Sennetts’ Keystone – the producer wanted to sack him. Normand also developed Chaplin’s ‘tramp’ screen personality. But she was, more or less, accidentally involved in the murder of William Desmond Taylor and the shooting of Courtland S. Dines, as well as being a friend (and co-star) of ‘Fatty’ Arbuckle, whose life was a series of scandals. Normand suffered for a long time from TB, interrupting her career and leading to her early death at the age of 37. NA-NOO-COBS-NEUN-SAN

NA-NOO-COBS-NEUN-SAN The Closing Night Gala, Eric Barbier’s Promise At Dawn will take place on 22 November at Curzon Mayfair and stars Pierre Niney with Charlotte Gainsbourg (Best Actress Cesar Nomination) playing the overbearing Jewish mother in a powerful adaptation of Romain Gary’s memoir.