Dir: Kon Ichikawa

“The soil of Burma is red, and so are its rocks” These are the words imposed on the opening scene of Kon Ichikawa’s THE BURMESE HARP. Nature has been disturbed by conflict. The blood of the bodies of Japanese and Burmese soldiers stains the landscape. It’s 1945 and the last day of the South Pacific War.

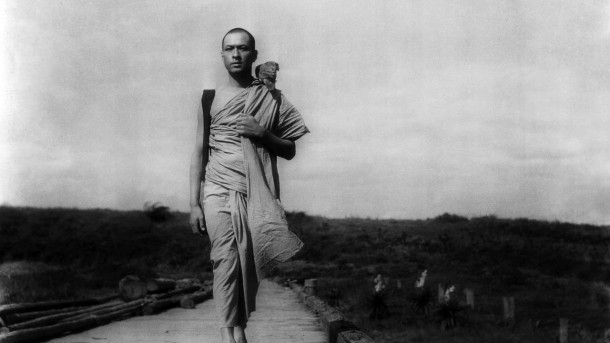

Private Mizushima (Yasui Shoji) is a harp player in a group of soldiers taught to sing by their captain. As a choir they sing to boost their morale, heal themselves and engage the Burmese peasants. The soldiers willingly surrender to the British Army, who then asks Mizushima if he will talk to another group of soldiers and persuade them to stop fighting. They will not, and are killed in one of the last conflicts of the war. Mizushima survives, adopting the garb of a monk and undertaking the gruesome burial of Japanese corpses in a spiritual re-awakening that marks the first ritual of his conversion to Buddhism. His honouring of the dead is a way of coming to terms with the terrible consequences of the war. Yet shouldn’t Mizushima really return home to his family like the rest of his fellow soldiers?

Critic Tony Rayns has said that of the thousands of soldiers who were re-patriated in 1945/46, many were treated badly by a population who were embarrassed by their return. In THE BURMESE HARP people talk of going home and hopefully returning to their former jobs, though this might be unlikely. Mizishima’s remaining in Burma is viewed as his own personal redemption and serves as a metaphor for a bigger spiritual journey that Japan must make.

One of the great pleasures of this ‘anti-war’ film is its sincere ‘pro-peace’ attitude – such moves towards peace being achieved through music. Unusually THE BURMESE HARP employs its soldiers as a choral work force. Throughout the film they sing the song “Hayu no Yado” (Home Sweet Home) making it a re-occurring motif for peace. Miraculously Ichikawa employs the song’s sentiment without ever making the film sentimental or sanctimonious. THE BURMESE HARP is a compassionate balm, never a pacifying sermon.

In an early scene the Japanese choir’s rendition of “Home Sweet Home” is reciprocated by a rendition by English and Australian soldiers. This beautifully staged event is imbued with a touching serenity. THE BURMESE HARP has very little action. The focus here is on the aftermath of war expressed through the power of music aligned to spiritual forces.

The texture of its black and white photography is astounding, especially in the outdoor scenes and those where statues of the Buddha are revealed. All the performances have a captivating naturalness and honesty that led to international acclaim for Kon Ichikawa in a film that remains to this day a haunting humanist statement about suffering and the need for spiritual detachment. Alan Price

NOW OUT ON BLURAY COURTESY OF EUREKA, MASTERS OF CINEMA