In Park City Utah, the SUNDANCE INSTITUTE sets the indie film agenda for 2017 with a slew of provocative new titles for this year’s festival which runs from 19-29 January. These will take part in the U.S. Competition, World Competition and NEXT strands, and an environmentally focused programme entitled New Climate.

In Park City Utah, the SUNDANCE INSTITUTE sets the indie film agenda for 2017 with a slew of provocative new titles for this year’s festival which runs from 19-29 January. These will take part in the U.S. Competition, World Competition and NEXT strands, and an environmentally focused programme entitled New Climate.

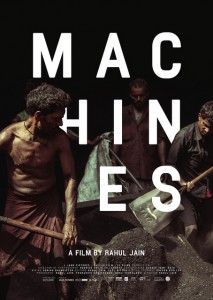

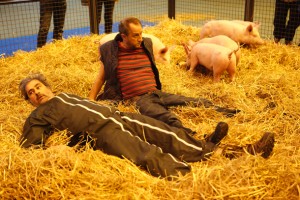

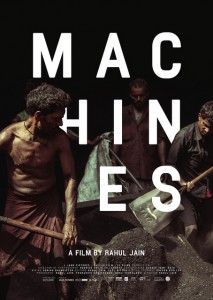

Robert Redford, President and Founder of Sundance, is joined by chief programmer John Copper programmer for 2017’s theme: climate change and environmental preservation. The New Climate program builds on the Institute’s longstanding commitment to showcasing environmental films and projects, that in the past have included An Inconvenient Truth, Blackfish, The Cove, Gasland, Chasing Ice, Racing Extinction and Collisions. This year’s programme includes Jeff Orlowski’s follow up to his coruscating documentary Chasing Ice, with Chasing Coral, which follows a team of divers, photographers and scientists exploring the world’s changing coral reefs; Trophy, an in-depth look at the controversial, multi-billion-dollar big-game hunting industry; Water & Power: A California Heist, an investigation of California’s convoluted water system; Plastic China an examination of employee life at a Chinese recycling plant; and Machines, (above) a portrait of the rhythm of life and work in a gigantic textile factory in Gujarat, India.

Robert Redford, President and Founder of Sundance, is joined by chief programmer John Copper programmer for 2017’s theme: climate change and environmental preservation. The New Climate program builds on the Institute’s longstanding commitment to showcasing environmental films and projects, that in the past have included An Inconvenient Truth, Blackfish, The Cove, Gasland, Chasing Ice, Racing Extinction and Collisions. This year’s programme includes Jeff Orlowski’s follow up to his coruscating documentary Chasing Ice, with Chasing Coral, which follows a team of divers, photographers and scientists exploring the world’s changing coral reefs; Trophy, an in-depth look at the controversial, multi-billion-dollar big-game hunting industry; Water & Power: A California Heist, an investigation of California’s convoluted water system; Plastic China an examination of employee life at a Chinese recycling plant; and Machines, (above) a portrait of the rhythm of life and work in a gigantic textile factory in Gujarat, India.

U.S. D R A M A T I C C O M P E T I T I O N

Presenting the world premieres of 16 narrative feature films, the Dramatic Competition offers Festivalgoers a first look at groundbreaking new voices in American independent film.

BAND AID / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Zoe Lister-Jones) — A couple who can’t stop arguing embark on a last-ditch effort to save their marriage: by turning their strife into songs and starting a band. Cast: Zoe Lister-Jones, Adam Pally, Fred Armisen, Susie Essman, Hannah Simone, Ravi Patel. World Premiere

BAND AID / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Zoe Lister-Jones) — A couple who can’t stop arguing embark on a last-ditch effort to save their marriage: by turning their strife into songs and starting a band. Cast: Zoe Lister-Jones, Adam Pally, Fred Armisen, Susie Essman, Hannah Simone, Ravi Patel. World Premiere

BEACH RATS/ U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Eliza Hittman) — An aimless teenager on the outer edges of Brooklyn struggles to escape his bleak home life and navigate questions of self-identity, as he balances his time between his delinquent friends, a potential new girlfriend, and older men he meets online. Cast: Harris Dickinson, Madeline Weinstein, Kate Hodge, Neal Huff. World Premiere

BRIGSBY BEAR/ U.S.A. (Director: Dave McCary, Screenwriters: Kevin Costello, Kyle Mooney) — Brigsby Bear Adventures is a children’s TV show produced for an audience of one: James. When the show abruptly ends, James’s life changes forever, and he sets out to finish the story himself. Cast: Kyle Mooney, Claire Danes, Mark Hamill, Greg Kinnear, Matt Walsh, Michaela Watkins. World Premiere

BRIGSBY BEAR/ U.S.A. (Director: Dave McCary, Screenwriters: Kevin Costello, Kyle Mooney) — Brigsby Bear Adventures is a children’s TV show produced for an audience of one: James. When the show abruptly ends, James’s life changes forever, and he sets out to finish the story himself. Cast: Kyle Mooney, Claire Danes, Mark Hamill, Greg Kinnear, Matt Walsh, Michaela Watkins. World Premiere

BURNING SANDS / U.S.A. (Director: Gerard McMurray, Screenwriters: Christine Berg, Gerard McMurray) — Deep into a fraternity’s Hell Week, a favoured pledge is torn between honouring a code of silence or standing up against the intensifying violence of underground hazing. Cast: Trevor Jackson, Alfre Woodard, Steve Harris, Tosin Cole, DeRon Horton, Trevante Rhodes. World Premiere

CROWN HEIGHTS / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Matt Ruskin) — When Colin Warner is wrongfully convicted of murder, his best friend, Carl King, devotes his life to proving Colin’s innocence. Adapted from This American Life, this is the incredible true story of their harrowing quest for justice. Cast: Keith Stanfield, Nnamdi Asomugha, Natalie Paul, Bill Camp, Nestor Carbonell, Amari Cheatom. World Premiere

GOLDEN EXITS/ U.S.A. left (Director and screenwriter: Alex Ross Perry) — The arrival of a young foreign girl disrupts the lives and emotional balances of two Brooklyn families. Cast: Emily Browning, Adam Horovitz, Mary-Louise Parker, Lily Rabe, Jason Schwartzman, Chloë Sevigny. World Premiere

GOLDEN EXITS/ U.S.A. left (Director and screenwriter: Alex Ross Perry) — The arrival of a young foreign girl disrupts the lives and emotional balances of two Brooklyn families. Cast: Emily Browning, Adam Horovitz, Mary-Louise Parker, Lily Rabe, Jason Schwartzman, Chloë Sevigny. World Premiere

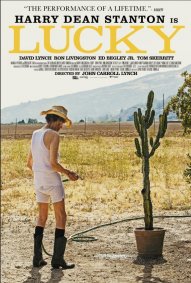

THE HERO / U.S.A. (Director: Brett Haley, Screenwriters: Brett Haley, Marc Basch) — Lee, a former Western film icon, is living a comfortable existence lending his golden voice to advertisements and smoking weed. After receiving a lifetime achievement award and unexpected news, Lee re-examines his past, while a chance meeting with a sardonic comic has him looking to the future. Cast: Sam Elliott, Laura Prepon, Krysten Ritter, Nick Offerman, Katherine Ross. World Premiere

I DON’T FEEL AT HOME IN THIS WORLD ANYMORE / U.S.A. left (Director and screenwriter: Macon Blair) — When a depressed woman is burgled, she finds a new sense of purpose by tracking down the thieves, alongside her obnoxious neighbour. But they soon find themselves dangerously out of their depth against a pack of degenerate criminals. Cast: Melanie Lynskey, Elijah Wood, David Yow, Jane Levy, Devon Graye. World Premiere. DAY ONE

I DON’T FEEL AT HOME IN THIS WORLD ANYMORE / U.S.A. left (Director and screenwriter: Macon Blair) — When a depressed woman is burgled, she finds a new sense of purpose by tracking down the thieves, alongside her obnoxious neighbour. But they soon find themselves dangerously out of their depth against a pack of degenerate criminals. Cast: Melanie Lynskey, Elijah Wood, David Yow, Jane Levy, Devon Graye. World Premiere. DAY ONE

INGRID GOES WEST / U.S.A. (Director: Matt Spicer, Screenwriters: Matt Spicer, David Branson Smith) — A young woman becomes obsessed with an Instagram lifestyle blogger and moves to Los Angeles to try and befriend her in real life. Cast: Aubrey Plaza, Elizabeth Olsen, O’Shea Jackson Jr., Wyatt Russell, Billy Magnussen. World Premiere

INGRID GOES WEST / U.S.A. (Director: Matt Spicer, Screenwriters: Matt Spicer, David Branson Smith) — A young woman becomes obsessed with an Instagram lifestyle blogger and moves to Los Angeles to try and befriend her in real life. Cast: Aubrey Plaza, Elizabeth Olsen, O’Shea Jackson Jr., Wyatt Russell, Billy Magnussen. World Premiere

LANDLINE/ U.S.A.- left (Director: Gillian Robespierre, Screenwriters: Elisabeth Holm, Gillian Robespierre) — Two sisters come of age in ’90s New York when they discover their dad’s affair—and it turns out he’s not the only cheater in the family. Everyone still smokes inside, no one has a cell phone and the Jacobs finally connect through lying, cheating and hibachi. Cast: Jenny Slate, John Turturro, Edie Falco, Abby Quinn, Jay Duplass, Finn Wittrock. World Premiere

LANDLINE/ U.S.A.- left (Director: Gillian Robespierre, Screenwriters: Elisabeth Holm, Gillian Robespierre) — Two sisters come of age in ’90s New York when they discover their dad’s affair—and it turns out he’s not the only cheater in the family. Everyone still smokes inside, no one has a cell phone and the Jacobs finally connect through lying, cheating and hibachi. Cast: Jenny Slate, John Turturro, Edie Falco, Abby Quinn, Jay Duplass, Finn Wittrock. World Premiere

NOVITIATE / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Maggie Betts) — In the early 1960s, during the Vatican II era, a young woman training to become a nun struggles with issues of faith, sexuality and the changing church. Cast: Margaret Qualley, Melissa Leo, Julianne Nicholson, Dianna Agron, Morgan Saylor. World Premiere

PATTI CAKE$ / U.S.A – left -. (Director and screenwriter: Geremy Jasper) — Straight out of Jersey comes Patricia Dombrowski, a.k.a. Killa P, a.k.a. Patti Cake$, an aspiring rapper fighting through a world of strip malls and strip clubs on an unlikely quest for glory. Cast: Danielle Macdonald, Bridget Everett, Siddharth Dhananjay, Mamoudou Athie, Cathy Moriarty. World Premiere

PATTI CAKE$ / U.S.A – left -. (Director and screenwriter: Geremy Jasper) — Straight out of Jersey comes Patricia Dombrowski, a.k.a. Killa P, a.k.a. Patti Cake$, an aspiring rapper fighting through a world of strip malls and strip clubs on an unlikely quest for glory. Cast: Danielle Macdonald, Bridget Everett, Siddharth Dhananjay, Mamoudou Athie, Cathy Moriarty. World Premiere

ROXANNE ROXANNE / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Michael Larnell) — The most feared battle emcee in early-’80s NYC was a fierce teenager from the Queensbridge projects with the weight of the world on her shoulders. At age 14, hustling the streets to provide for her family, Roxanne Shanté was well on her way to becoming a hip-hop legend. Cast: Chanté Adams, Mahershala Ali, Nia Long, Elvis Nolasco, Kevin Phillips, Shenell Edmonds. World Premiere

TO THE BONE / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Marti Noxon) — In a last-ditch effort to battle her severe anorexia, 20-year-old Ellen enters a group recovery home. With the help of an unconventional doctor, Ellen and the other residents go on a sometimes-funny, sometimes-harrowing journey that leads to the ultimate question—is life worth living? Cast: Lily Collins, Keanu Reeves, Carrie Preston, Lili Taylor, Alex Sharp, Liana Liberato. World Premiere

WALKING OUT / U.S.A. (Directors and screenwriters: Alex Smith, Andrew Smith) — A father and son struggle to connect on any level until a brutal encounter with a predator in the heart of the wilderness leaves them both seriously injured. If they are to survive, the boy must carry his father to safety. Cast: Matt Bomer, Josh Wiggins, Bill Pullman, Alex Neustaedter, Lily Gladstone. World Premiere

WALKING OUT / U.S.A. (Directors and screenwriters: Alex Smith, Andrew Smith) — A father and son struggle to connect on any level until a brutal encounter with a predator in the heart of the wilderness leaves them both seriously injured. If they are to survive, the boy must carry his father to safety. Cast: Matt Bomer, Josh Wiggins, Bill Pullman, Alex Neustaedter, Lily Gladstone. World Premiere

THE YELLOW BIRDS/ U.S.A.- left- (Director: Alexandre Moors, Screenwriter: David Lowery) — Two young men enlist in the army and are deployed to fight in the Gulf War. After an unthinkable tragedy, the surviving soldier struggles to balance his promise of silence with the truth and a mourning mother’s search for peace. Cast: Tye Sheridan, Jack Huston, Alden Ehrenreich, Jason Patric, Toni Collette, Jennifer Aniston. World Premiere

THE YELLOW BIRDS/ U.S.A.- left- (Director: Alexandre Moors, Screenwriter: David Lowery) — Two young men enlist in the army and are deployed to fight in the Gulf War. After an unthinkable tragedy, the surviving soldier struggles to balance his promise of silence with the truth and a mourning mother’s search for peace. Cast: Tye Sheridan, Jack Huston, Alden Ehrenreich, Jason Patric, Toni Collette, Jennifer Aniston. World Premiere

U. S. D O C U M E N T A R Y C O M P E T I T I O N

Sixteen world-premiere American documentaries that illuminate the ideas, people and events that shape the present day.

CASTING JONBENET / U.S.A., Australia (Director: Kitty Green) — The unsolved death of six-year-old American beauty queen JonBenet Ramsey remains the world’s most sensational child murder case. Over 15 months, responses, reflections and performances were elicited from the Ramsey’s Colorado hometown community, creating a bold work of art from the collective memories and mythologies the crime inspired. World Premiere

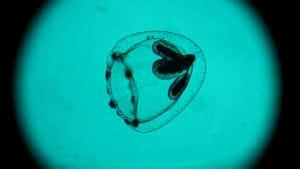

CHASING CORAL/ U.S.A. (Director: Jeff Orlowski) — Coral reefs around the world are vanishing at an unprecedented rate. A team of divers, photographers and scientists set out on a thrilling ocean adventure to discover why and to reveal the underwater mystery to the world. World Premiere. NEW CLIMATE

CHASING CORAL/ U.S.A. (Director: Jeff Orlowski) — Coral reefs around the world are vanishing at an unprecedented rate. A team of divers, photographers and scientists set out on a thrilling ocean adventure to discover why and to reveal the underwater mystery to the world. World Premiere. NEW CLIMATE

CITY OF GHOSTS/ U.S.A. (Director: Matthew Heineman) — With unprecedented access, this documentary follows the extraordinary journey of “Raqqa is Being Slaughtered Silently”—a group of anonymous citizen journalists who banded together after their homeland was overtaken by ISIS—as they risk their lives to stand up against one of the greatest evils in the world today. World PremiereD

DINA/ U.S.A. (Directors: Dan Sickles, Antonio Santini) — An eccentric suburban woman and a Walmart door-greeter navigate their evolving relationship in this unconventional love story. World Premiere

DOLORES/ U.S.A – left – (Director: Peter Bratt) — Dolores Huerta bucks 1950s gender conventions by co-founding the country’s first farmworkers’ union. Wrestling with raising 11 children, gender bias, union defeat and victory, and nearly dying after a San Francisco Police beating, Dolores emerges with a vision that connects her newfound feminism with racial and class justice. World Premiere

DOLORES/ U.S.A – left – (Director: Peter Bratt) — Dolores Huerta bucks 1950s gender conventions by co-founding the country’s first farmworkers’ union. Wrestling with raising 11 children, gender bias, union defeat and victory, and nearly dying after a San Francisco Police beating, Dolores emerges with a vision that connects her newfound feminism with racial and class justice. World Premiere

THE FORCE / U.S.A. (Director: Pete Nicks) — This cinema vérité look at the long-troubled Oakland Police Department goes deep inside their struggles to confront federal demands for reform, a popular uprising following events in Ferguson and an explosive scandal. World Premiere

ICARUS / U.S.A. (Director: Bryan Fogel) — When Bryan Fogel sets out to uncover the truth about doping in sports, a chance meeting with a Russian scientist transforms his story from a personal experiment into a geopolitical thriller involving dirty urine, unexplained death and Olympic Gold—exposing the biggest scandal in sports history. World Premiere

ICARUS / U.S.A. (Director: Bryan Fogel) — When Bryan Fogel sets out to uncover the truth about doping in sports, a chance meeting with a Russian scientist transforms his story from a personal experiment into a geopolitical thriller involving dirty urine, unexplained death and Olympic Gold—exposing the biggest scandal in sports history. World Premiere

THE NEW RADICAL / U.S.A. (Director: Adam Bhala Lough) — Uncompromising millennial radicals from the United States and the United Kingdom attack the system through dangerous technological means, which evolves into a high-stakes game with world authorities in the midst of a dramatically changing political landscape. World Premiere

NOBODY SPEAK: Hulk Hogan, Gawker and Trials of a Free Press / U.S.A. (Director: Brian Knappenberger) — The trial between Hulk Hogan and Gawker Media pitted privacy rights against freedom of the press, and raised important questions about how big money can silence media. This film is an examination of the perils and duties of the free press in an age of inequality. World Premiere

QUEST / U.S.A. (Director: Jonathan Olshefski) — For over a decade, this portrait of a North Philadelphia family and the creative sanctuary offered by their home music studio was filmed with vérité intimacy. The family’s 10-year journey is an illumination of race and class in America, and it’s a testament to love, healing and hope. World Premiere

QUEST / U.S.A. (Director: Jonathan Olshefski) — For over a decade, this portrait of a North Philadelphia family and the creative sanctuary offered by their home music studio was filmed with vérité intimacy. The family’s 10-year journey is an illumination of race and class in America, and it’s a testament to love, healing and hope. World Premiere

STEP / U.S.A. (Director: Amanda Lipitz) — The senior year of a girls’ high school step team in inner-city Baltimore is documented, as they try to become the first in their families to attend college. The girls strive to make their dancing a success against the backdrop of social unrest in their troubled city. World Premiere

STRONG ISLAND / U.S.A., Denmark (Director: Yance Ford) — Examining the violent death of the filmmaker’s brother and the judicial system that allowed his killer to go free, this documentary interrogates murderous fear and racialized perception, and re-imagines the wreckage in catastrophe’s wake, challenging us to change. World Premiere

TROPHY / U.S.A.- left- (Director: Shaul Schwarz, Co-Director: Christina Clusiau) — This in-depth look into the powerhouse industries of big-game hunting, breeding and wildlife conservation in the U.S. and Africa unravels the complex consequences of treating animals as commodities. World Premiere. NEW CLIMATE

TROPHY / U.S.A.- left- (Director: Shaul Schwarz, Co-Director: Christina Clusiau) — This in-depth look into the powerhouse industries of big-game hunting, breeding and wildlife conservation in the U.S. and Africa unravels the complex consequences of treating animals as commodities. World Premiere. NEW CLIMATE

UNREST / U.S.A. (Director: Jennifer Brea) — When Harvard PhD student Jennifer Brea is struck down at 28 by a fever that leaves her bedridden, doctors tell her it’s “all in her head.” Determined to live, she sets out on a virtual journey to document her story—and four other families’ stories—fighting a disease medicine forgot. World Premiere

Water & Power: A California Heist / U.S.A. (Director: Marina Zenovich) — In California’s convoluted water system, notorious water barons find ways to structure a state-engineered system to their own advantage. This examination into their centers of power shows small farmers and everyday citizens facing drought and a new, debilitating groundwater crisis. World Premiere. NEW CLIMATE

Water & Power: A California Heist / U.S.A. (Director: Marina Zenovich) — In California’s convoluted water system, notorious water barons find ways to structure a state-engineered system to their own advantage. This examination into their centers of power shows small farmers and everyday citizens facing drought and a new, debilitating groundwater crisis. World Premiere. NEW CLIMATE

WHOSE STREETS? / U.S.A. (Director: Sabaah Folayan, Co-Director: Damon Davis) — A nonfiction account of the Ferguson uprising told by the people who lived it, this is an unflinching look at how the killing of 18-year-old Michael Brown inspired a community to fight back—and sparked a global movement. World Premiere. DAY ONE

WHOSE STREETS? / U.S.A. (Director: Sabaah Folayan, Co-Director: Damon Davis) — A nonfiction account of the Ferguson uprising told by the people who lived it, this is an unflinching look at how the killing of 18-year-old Michael Brown inspired a community to fight back—and sparked a global movement. World Premiere. DAY ONE

W O R L D C I N E M A D R A M A T I C C O M P E T I T I O N

Twelve films from emerging filmmaking talents around the world offer fresh perspectives and inventive styles.

AXOLOT! OVERKILL/ Germany (Director and screenwriter: Helene Hegemann) — Mifti, age 16, lives in Berlin with a cast of characters including her half-siblings; their rich, self-involved father; and her junkie friend Ophelia. As she mourns her recently deceased mother, she begins to develop an obsession with Alice, an enigmatic, and much older, white-collar criminal. Cast: Jasna Fritzi Bauer, Arly Jover, Mavie Hörbiger, Laura Tonke, Hans Löw, Bernhard Schütz. World Premiere

AXOLOT! OVERKILL/ Germany (Director and screenwriter: Helene Hegemann) — Mifti, age 16, lives in Berlin with a cast of characters including her half-siblings; their rich, self-involved father; and her junkie friend Ophelia. As she mourns her recently deceased mother, she begins to develop an obsession with Alice, an enigmatic, and much older, white-collar criminal. Cast: Jasna Fritzi Bauer, Arly Jover, Mavie Hörbiger, Laura Tonke, Hans Löw, Bernhard Schütz. World Premiere

BERLIN SYNDROME/ Australia (Director: Cate Shortland, Screenwriter: Shaun Grant) — A passionate holiday romance takes an unexpected and sinister turn when an Australian photographer wakes one morning in a Berlin apartment and is unable to leave. Cast: Teresa Palmer, Max Riemelt. World Premiere

BERLIN SYNDROME/ Australia (Director: Cate Shortland, Screenwriter: Shaun Grant) — A passionate holiday romance takes an unexpected and sinister turn when an Australian photographer wakes one morning in a Berlin apartment and is unable to leave. Cast: Teresa Palmer, Max Riemelt. World Premiere

CARPINTEROS (Woodpeckers) / Dominican Republic (Director and screenwriter: José María Cabral) — Julián finds love and a reason for living in the last place imaginable: the Dominican Republic’s Najayo Prison. His romance with fellow prisoner Yanelly must develop through sign language and without the knowledge of dozens of guards. Cast: Jean Jean, Judith Rodriguez Perez, Ramón Emilio Candelario. World Premiere

DON’T SWALLOW MY HEART, ALLIGATOR GIRL!/ Brazil, Netherlands, France, Paraguay (Director and screenwriter: Felipe Bragança) — In this fable about love and memories, Joca is a 13-year-old Brazilian boy in love with an indigenous Paraguayan girl. To conquer her love, he must face the violent region’s war-torn past and the secrets of his elder brother, Fernando, a motorcycle cowboy. Cast: Cauã Reymond, Eduardo Macedo, Adeli Gonzales, Zahy Guajajara, Claudia Assunção, Ney Matogrosso. World Premiere

DON’T SWALLOW MY HEART, ALLIGATOR GIRL!/ Brazil, Netherlands, France, Paraguay (Director and screenwriter: Felipe Bragança) — In this fable about love and memories, Joca is a 13-year-old Brazilian boy in love with an indigenous Paraguayan girl. To conquer her love, he must face the violent region’s war-torn past and the secrets of his elder brother, Fernando, a motorcycle cowboy. Cast: Cauã Reymond, Eduardo Macedo, Adeli Gonzales, Zahy Guajajara, Claudia Assunção, Ney Matogrosso. World Premiere

FAMILY LIFE/ Chile (Directors: Alicia Scherson, Cristián Jiménez, Screenwriter: Alejandro Zambra) — While house-sitting for a distant cousin, a lonely man fabricates the existence of a vindictive ex-wife withholding his daughter, in order to gain the sympathy of the single mother he has just met. Cast: Jorge Becker, Gabriela Arancibia, Blanca Lewin, Cristián Carvajal. World Premiere

FREE AND EASY / Hong Kong (Director: Jun Geng, Screenwriters: Jun Geng, Yuhua Feng, Bing Liu) — When a traveling soap salesman arrives in a desolate Chinese town, a crime occurs, and sets the strange residents against each other with tragicomic results. Cast: Gang Xu, Zhiyong Zhang, Baohe Xue, Benshan Gu, Xun Zhang. World Premiere

GOD’S OWN COUNTRY / United Kingdom (Director and screenwriter: Francis Lee) — Springtime in Yorkshire: isolated young sheep farmer Johnny Saxby numbs his daily frustrations with binge drinking and casual sex, until the arrival of a Romanian migrant worker, employed for the lambing season, ignites an intense relationship that sets Johnny on a new path. Cast: Josh O’Connor, Alec Secareanu, Ian Hart, Gemma Jones. World Premiere

GOD’S OWN COUNTRY / United Kingdom (Director and screenwriter: Francis Lee) — Springtime in Yorkshire: isolated young sheep farmer Johnny Saxby numbs his daily frustrations with binge drinking and casual sex, until the arrival of a Romanian migrant worker, employed for the lambing season, ignites an intense relationship that sets Johnny on a new path. Cast: Josh O’Connor, Alec Secareanu, Ian Hart, Gemma Jones. World Premiere

MY HAPPY FAMILY / Georgia (Directors: Nana & Simon, Screenwriter: Nana Ekvtimishvili) — Tbilisi, Georgia, 2016: In a patriarchal society, an ordinary Georgian family lives with three generations under one roof. All are shocked when 52-year-old Manana decides to move out from her parents’ home and live alone. Without her family and her husband, a journey into the unknown begins. Cast: Ia Shugliashvili, Merab Ninidze, Berta Khapava, Tsisia Qumsishvili, Giorgi Tabidze, Dimitri Oragvelidze. World Premiere

THE NILE HILTON INCIDENT / Sweden (Director and screenwriter: Tarik Saleh) — In Cairo, weeks before the 2011 revolution, Police Detective Noredin is working in the infamous Kasr el-Nil Police Station when he is handed the case of a murdered singer. He soon realizes that the investigation concerns the power elite, close to the President’s inner circle. Cast: Fares Fares, Mari Malek, Mohamed Yousry, Yasser Ali Maher, Ahmed Selim, Hania Amar. World Premiere

THE NILE HILTON INCIDENT / Sweden (Director and screenwriter: Tarik Saleh) — In Cairo, weeks before the 2011 revolution, Police Detective Noredin is working in the infamous Kasr el-Nil Police Station when he is handed the case of a murdered singer. He soon realizes that the investigation concerns the power elite, close to the President’s inner circle. Cast: Fares Fares, Mari Malek, Mohamed Yousry, Yasser Ali Maher, Ahmed Selim, Hania Amar. World Premiere

POP EYE / Singapore, Thailand (Director and screenwriter: Kirsten Tan) — On a chance encounter, a disenchanted architect bumps into his long-lost elephant on the streets of Bangkok. Excited, he takes his elephant on a journey across Thailand in search of the farm where they grew up together. Cast: Thaneth Warakulnukroh, Penpak Sirikul, Bong. World Premiere. DAY ONE

POP EYE / Singapore, Thailand (Director and screenwriter: Kirsten Tan) — On a chance encounter, a disenchanted architect bumps into his long-lost elephant on the streets of Bangkok. Excited, he takes his elephant on a journey across Thailand in search of the farm where they grew up together. Cast: Thaneth Warakulnukroh, Penpak Sirikul, Bong. World Premiere. DAY ONE

SUENO EN OTRO IDIOMA (I Dream in Another Language) / Mexico (Director: Ernesto Contreras, Screenwriter: Carlos Contreras) — The last two speakers of a millennia-old language haven’t spoken in 50 years, when a young linguist tries to bring them together. Yet hidden in the past, in the heart of the jungle, lies a secret concerning the fate of the Zikril language. Cast: Fernando Álvarez Rebeil, Eligio Meléndez, Manuel Poncelis, Fátima Molina, Juan Pablo de Santiago, Hoze Meléndez. World Premiere

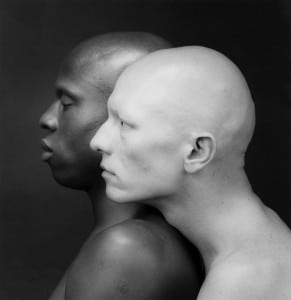

THE WOUND / South Africa (Director: John Trengove, Screenwriters: John Trengove, Thando Mgqolozana, Malusi Bengu) — Xolani, a lonely factory worker, travels to the rural mountains with the men of his community to initiate a group of teenage boys into manhood. When a defiant initiate from the city discovers his best-kept secret, a forbidden love, Xolani’s entire existence begins to unravel. Cast: Nakhane Touré, Bongile Mantsai, Niza Jay Ncoyini. World Premiere

THE WOUND / South Africa (Director: John Trengove, Screenwriters: John Trengove, Thando Mgqolozana, Malusi Bengu) — Xolani, a lonely factory worker, travels to the rural mountains with the men of his community to initiate a group of teenage boys into manhood. When a defiant initiate from the city discovers his best-kept secret, a forbidden love, Xolani’s entire existence begins to unravel. Cast: Nakhane Touré, Bongile Mantsai, Niza Jay Ncoyini. World Premiere

W O R L D C I N E M A D O C U M E N T A R Y C O M P E T I T I O N

Twelve documentaries by some of the most courageous and extraordinary international filmmakers working today.

THE GOOD POSTMAN / Finland, Bulgaria (Director: Tonislav Hristov) — In a small Bulgarian village troubled by the ongoing refugee crisis, a local postman runs for mayor—and learns that even minor deeds can outweigh good intentions. North American Premiere

THE GOOD POSTMAN / Finland, Bulgaria (Director: Tonislav Hristov) — In a small Bulgarian village troubled by the ongoing refugee crisis, a local postman runs for mayor—and learns that even minor deeds can outweigh good intentions. North American Premiere

IN LOCO PARENTIS / Ireland, Spain (Directors: Neasa Ní Chianáin, David Rane) — John and Amanda teach Latin, English and guitar at a fantastical, stately home-turned-school. Nearly 50-year careers are drawing to a close for the pair who have become legends with the mantra: “Reading! ’Rithmetic! Rock ’n’ roll!” But for pupil and teacher alike, leaving is the hardest lesson. North American Premiere

IN LOCO PARENTIS / Ireland, Spain (Directors: Neasa Ní Chianáin, David Rane) — John and Amanda teach Latin, English and guitar at a fantastical, stately home-turned-school. Nearly 50-year careers are drawing to a close for the pair who have become legends with the mantra: “Reading! ’Rithmetic! Rock ’n’ roll!” But for pupil and teacher alike, leaving is the hardest lesson. North American Premiere

IT’S NOT DARK YET / Ireland (Director: Frankie Fenton) — This is the incredible story of Simon Fitzmaurice, a young filmmaker who becomes completely paralyzed from motor neurone disease but goes on to direct an award-winning feature film through the use of his eyes. International Premiere

JOSHUA: TEENAGE VRS SUPERPOWER / U.S.A. (Director: Joe Piscatella) — When the Chinese Communist Party backtracks on its promise of autonomy to Hong Kong, teenager Joshua Wong decides to save his city. Rallying thousands of kids to skip school and occupy the streets, Joshua becomes an unlikely leader in Hong Kong and one of China’s most notorious dissidents. World Premiere

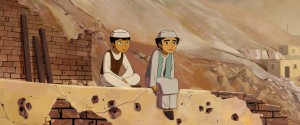

LAST MEN IN ALEPPO/ Denmark (Directors: Feras Fayyad, Steen Johannessen) — After five years of war in Syria, Aleppo’s remaining residents prepare themselves for a siege. Khalid, Subhi and Mahmoud, founding members of The White Helmets, have remained in the city to help their fellow citizens—and experience daily life, death, struggle and triumph in a city under fire. World Premiere

LAST MEN IN ALEPPO/ Denmark (Directors: Feras Fayyad, Steen Johannessen) — After five years of war in Syria, Aleppo’s remaining residents prepare themselves for a siege. Khalid, Subhi and Mahmoud, founding members of The White Helmets, have remained in the city to help their fellow citizens—and experience daily life, death, struggle and triumph in a city under fire. World Premiere

MACHINES / India, Germany, Finland (Director: Rahul Jain) — This intimate, observant portrayal of the rhythm of life and work in a gigantic textile factory in Gujarat, India, moves through the corridors and bowels of the enormously disorienting structure—taking the viewer on a journey of dehumanizing physical labor and intense hardship. North American Premiere. NEW CLIMATE

MACHINES / India, Germany, Finland (Director: Rahul Jain) — This intimate, observant portrayal of the rhythm of life and work in a gigantic textile factory in Gujarat, India, moves through the corridors and bowels of the enormously disorienting structure—taking the viewer on a journey of dehumanizing physical labor and intense hardship. North American Premiere. NEW CLIMATE

MOTHERLAND/ U.S.A., Philippines (Director: Ramona Diaz) — The planet’s busiest maternity hospital is located in one of its poorest and most populous countries: the Philippines. There, poor women face devastating consequences as their country struggles with reproductive health policy and the politics of conservative Catholic ideologies. World Premiere

PLASTIC CHINA/ China (Director: Jiu-liang Wang) — Yi-Jie, an 11-year-old girl, works alongside her parents in a recycling facility while dreaming of attending school. Kun, the facility’s ambitious foreman, dreams of a better life. Through the eyes and hands of those who handle its refuse, comes an examination of global consumption and culture. International Premiere. NEW CLIMATE

PLASTIC CHINA/ China (Director: Jiu-liang Wang) — Yi-Jie, an 11-year-old girl, works alongside her parents in a recycling facility while dreaming of attending school. Kun, the facility’s ambitious foreman, dreams of a better life. Through the eyes and hands of those who handle its refuse, comes an examination of global consumption and culture. International Premiere. NEW CLIMATE

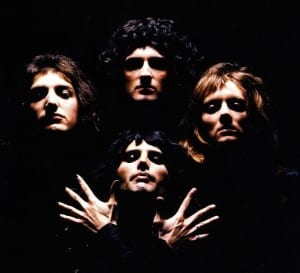

RUMBLE: The Indians Who Rocked The World / Canada (Director: Catherine Bainbridge) — This powerful documentary about the role of Native Americans in contemporary music history—featuring some of the greatest music stars of our time—exposes a critical missing chapter, revealing how indigenous musicians helped shape the soundtracks of our lives and, through their contributions, influenced popular culture. World Premiere

TOKYO IDOLS / United Kingdom, Canada (Director: Kyoko Miyake) — This exploration of Japan’s fascination with girl bands and their music follows an aspiring pop singer and her fans, delving into the cultural obsession with young female sexuality and the growing disconnect between men and women in hypermodern societies. World Premiere

WINNIE / France (Director: Pascale Lamche) — While her husband served a life sentence, paradoxically kept safe and morally uncontaminated, Winnie Mandela rode the raw violence of apartheid, fighting on the front line and underground. This is the untold story of the mysterious forces that combined to take her down, labeling him a saint, her, a sinner. World Premiere

WINNIE / France (Director: Pascale Lamche) — While her husband served a life sentence, paradoxically kept safe and morally uncontaminated, Winnie Mandela rode the raw violence of apartheid, fighting on the front line and underground. This is the untold story of the mysterious forces that combined to take her down, labeling him a saint, her, a sinner. World Premiere

THE WORKERS CUP / United Kingdom (Director: Adam Sobel) — Inside Qatar’s labour camps, African and Asian migrant workers building the facilities of the 2022 World Cup compete in a football tournament of their own. World Premiere. DAY ONE

THE WORKERS CUP / United Kingdom (Director: Adam Sobel) — Inside Qatar’s labour camps, African and Asian migrant workers building the facilities of the 2022 World Cup compete in a football tournament of their own. World Premiere. DAY ONE

N E X T

Pure, bold works distinguished by an innovative, forward-thinking approach to storytelling populate this programme. Digital technology paired with unfettered creativity promises that the films in this section will shape a “greater” next wave in American cinema. Presented by Adobe.

COLUMBUS / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Kogonada) — Casey lives with her mother in a little-known Midwestern town haunted by the promise of modernism. Jin, a visitor from the other side of the world, attends to his dying father. Burdened by the future, they find respite in one another and the architecture that surrounds them. Cast: John Cho, Haley Lu Richardson, Parker Posey, Rory Culkin, Michelle Forbes. World Premiere

COLUMBUS / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Kogonada) — Casey lives with her mother in a little-known Midwestern town haunted by the promise of modernism. Jin, a visitor from the other side of the world, attends to his dying father. Burdened by the future, they find respite in one another and the architecture that surrounds them. Cast: John Cho, Haley Lu Richardson, Parker Posey, Rory Culkin, Michelle Forbes. World Premiere

DAYVEON/ U.S.A. (Director: Amman Abbasi, Screenwriters: Amman Abbasi, Steven Reneau) — In the wake of his older brother’s death, 13-year-old Dayveon spends the sweltering summer days roaming his rural Arkansas town. When he falls in with a local gang, he becomes drawn to the camaraderie and violence of their world. Cast: Devin Blackmon, Kordell “KD” Johnson, Dontrell Bright, Chasity Moore, Lachion Buckingham, Marquell Manning. World Premiere. DAY ONE

DEIDRA & LANEY ROB A TRAIN / U.S.A. (Director: Sydney Freeland, Screenwriter: Shelby Farrell) — Two teenage sisters start robbing trains to make ends meet after their single mother’s emotional meltdown in an electronics store lands her in jail. Cast: Ashleigh Murray, Rachel Crow, Tim Blake Nelson, David Sullivan, Danielle Nicolet, Sasheer Zamata. World Premiere

DEIDRA & LANEY ROB A TRAIN / U.S.A. (Director: Sydney Freeland, Screenwriter: Shelby Farrell) — Two teenage sisters start robbing trains to make ends meet after their single mother’s emotional meltdown in an electronics store lands her in jail. Cast: Ashleigh Murray, Rachel Crow, Tim Blake Nelson, David Sullivan, Danielle Nicolet, Sasheer Zamata. World Premiere

A GHOST STORY / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: David Lowery) — This is the story of a ghost and the house he haunts. Cast: Casey Affleck, Rooney Mara, Will Oldham, Sonia Acevedo, Rob Zabrecky, Liz Franke. World Premiere

GOOK / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Justin Chon) — Eli and Daniel, two Korean American brothers who own a struggling women’s shoe store, have an unlikely friendship with 11-year-old Kamilla. On the first day of the 1992 L.A. riots, the trio must defend their store—and contemplate the meaning of family, their personal dreams and the future. Cast: Justin Chon, Simone Baker, David So, Curtiss Cook Jr., Sang Chon, Ben Munoz. World Premiere

GOOK / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Justin Chon) — Eli and Daniel, two Korean American brothers who own a struggling women’s shoe store, have an unlikely friendship with 11-year-old Kamilla. On the first day of the 1992 L.A. riots, the trio must defend their store—and contemplate the meaning of family, their personal dreams and the future. Cast: Justin Chon, Simone Baker, David So, Curtiss Cook Jr., Sang Chon, Ben Munoz. World Premiere

L.A. TIMES / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Michelle Morgan) — In this classically styled comedy of manners set in Los Angeles, sophisticated thirtysomethings try to determine whether ideal happiness exists in coupledom or if the perfectly suited couple is actually just an urban myth. Cast: Michelle Morgan, Dree Hemingway, Jorma Taccone, Kentucker Audley, Margarita Levieva, Adam Shapiro. World Premiere

L.A. TIMES / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Michelle Morgan) — In this classically styled comedy of manners set in Los Angeles, sophisticated thirtysomethings try to determine whether ideal happiness exists in coupledom or if the perfectly suited couple is actually just an urban myth. Cast: Michelle Morgan, Dree Hemingway, Jorma Taccone, Kentucker Audley, Margarita Levieva, Adam Shapiro. World Premiere

LEMON/ U.S.A. (Director: Janicza Bravo, Screenwriters: Janicza Bravo, Brett Gelman) — A man watches his life unravel after he is left by his blind girlfriend. Cast: Brett Gelman, Judy Greer, Michael Cera, Nia Long, Shiri Appleby, Fred Melamed. World Premiere

MENASHE / U.S.A. (Director: Joshua Z Weinstein, Screenwriters: Joshua Z Weinstein, Alex Lipschultz, Musa Syeed) — Within Brooklyn’s ultra-orthodox Jewish community, a widower battles for custody of his son. A tender drama performed entirely in Yiddish, the film intimately explores the nature of faith and the price of parenthood. Cast: Menashe Lustig. World Premiere

PERSON TO PERSON / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Dustin Guy Defa) — A record collector hustles for a big score while his heartbroken roommate tries to erase a terrible mistake, a teenager bears witness to her best friend’s new relationship and a rookie reporter, alongside her demanding supervisor, chases the clues of a murder case involving a life-weary clock shop owner. Cast: Abbi Jacobson, Michael Cera, Tavi Gevinson, Philip Baker Hall, Bene Coopersmith, George Sample III. World Premiere

THOROUGHBRED / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Cory Finley) — Two teenage girls in suburban Connecticut rekindle their unlikely friendship after years of growing apart. In the process, they learn that neither is what she seems to be—and that a murder might solve both of their problems. Cast: Olivia Cooke, Anya Taylor-Joy, Anton Yelchin, Paul Sparks, Francie Swift, Kaili Vernoff. World Premiere

THOROUGHBRED / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Cory Finley) — Two teenage girls in suburban Connecticut rekindle their unlikely friendship after years of growing apart. In the process, they learn that neither is what she seems to be—and that a murder might solve both of their problems. Cast: Olivia Cooke, Anya Taylor-Joy, Anton Yelchin, Paul Sparks, Francie Swift, Kaili Vernoff. World Premiere

SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL \ 19-29 JANUARY 2017

CINEMA MADE IN ITALY returns to London’s Ciné Lumière, showcasing the latest releases from Italy complete with film-maker Q&A sessions. This year’s line-up includes eight new Italian films and a 1977 classic title

CINEMA MADE IN ITALY returns to London’s Ciné Lumière, showcasing the latest releases from Italy complete with film-maker Q&A sessions. This year’s line-up includes eight new Italian films and a 1977 classic title

In LA NOTTE (1960) allows us to share a day in the company of the writer Giovanni and his wife Lydia. When their friend dies in a hospital, they realise that their own love for each other has also been dead for quite a while. Antonioni uses his characters like figures on a chess board. They are real, but at the same time cyphers. He does not tell their story, but follows their movements from one place to an another. There is no interconnection between them and their environment. They have lost all feeling for themselves, others and the outside world. Their world is cold and threatening. Antonioni offers no irony or pity. He is the surgeon at the operating table, and his view is that of the camera: mostly skewed over-head shots. It is impossible to love La Notte. Whilst Antonioni was the first director of the modern era, he is also its most vicious critic.

In LA NOTTE (1960) allows us to share a day in the company of the writer Giovanni and his wife Lydia. When their friend dies in a hospital, they realise that their own love for each other has also been dead for quite a while. Antonioni uses his characters like figures on a chess board. They are real, but at the same time cyphers. He does not tell their story, but follows their movements from one place to an another. There is no interconnection between them and their environment. They have lost all feeling for themselves, others and the outside world. Their world is cold and threatening. Antonioni offers no irony or pity. He is the surgeon at the operating table, and his view is that of the camera: mostly skewed over-head shots. It is impossible to love La Notte. Whilst Antonioni was the first director of the modern era, he is also its most vicious critic.

The Crowhurst story has spawned various theatrical and literary adaptations, and even a chamber opera: The Strange Last Voyage of Donald Crowhurst. Eric Colvin plays him in Simon Rumley’s upcoming low budget indie thriller Crowhurst which purportedly features the actual vessel that set sail in the endeavour.

The Crowhurst story has spawned various theatrical and literary adaptations, and even a chamber opera: The Strange Last Voyage of Donald Crowhurst. Eric Colvin plays him in Simon Rumley’s upcoming low budget indie thriller Crowhurst which purportedly features the actual vessel that set sail in the endeavour. Firth is brilliantly cast as Crowhurst – blending just the right amount of pathos and self-belief in his portrait of an unsatisfactory businessman of a rather nervous disposition who can’t take pressure and lacks personal conviction (possibly due to his mother dressing him as a much wanted girl until the age of 17). His marriage is clearly happy and Rachel Weisz plays his wife as a typically supportive English rose, stalwart in her affections and a brilliant mum but rather passive and naive in a commercial sense, as most women were in the those days.

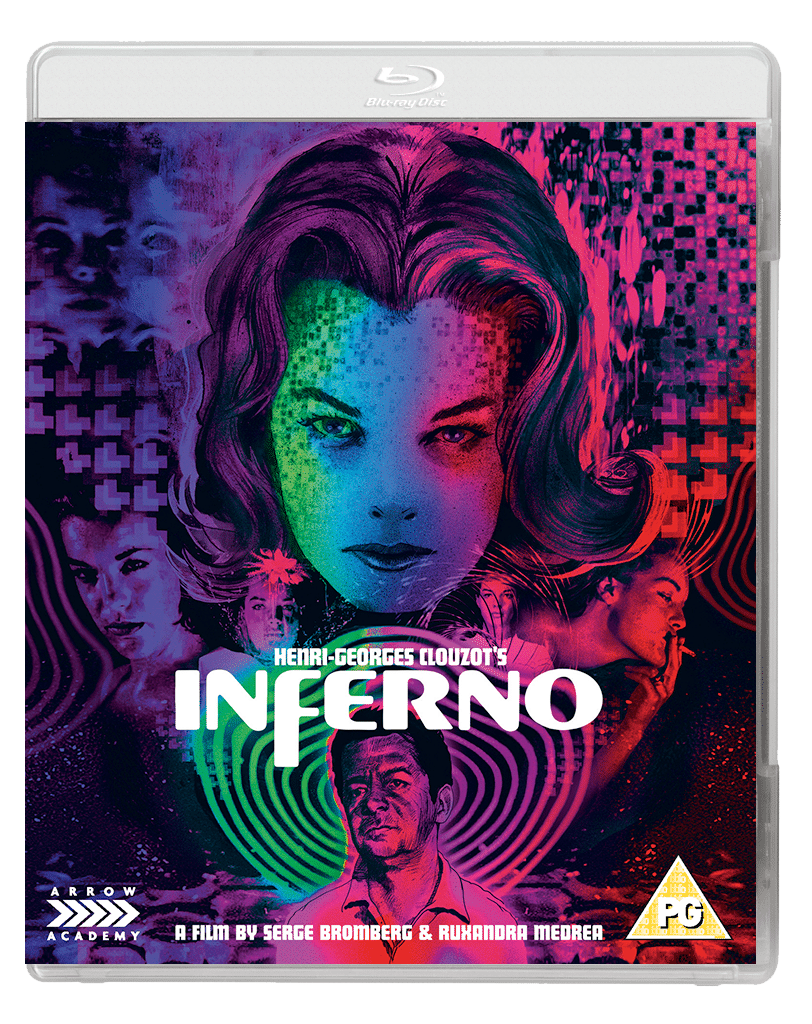

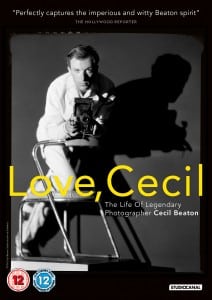

Firth is brilliantly cast as Crowhurst – blending just the right amount of pathos and self-belief in his portrait of an unsatisfactory businessman of a rather nervous disposition who can’t take pressure and lacks personal conviction (possibly due to his mother dressing him as a much wanted girl until the age of 17). His marriage is clearly happy and Rachel Weisz plays his wife as a typically supportive English rose, stalwart in her affections and a brilliant mum but rather passive and naive in a commercial sense, as most women were in the those days. This year’s Berlin International Film Festival is awarding the American actor Willem Defoe with an Honorary Golden Bear in recognition of his career featuring over 100 performances and spanning nearly 40 years since his 1981 debut in Kathryn Bigelow’s debut drama The Loveless. His enormous technical range as an actor extends all the way from the personification of the unfathomably evil to the portrayal of Jesus of Nazareth. In addition to his celebrated cinematic appearances, Dafoe has also pursued a parallel career in theatre, his other passion.

This year’s Berlin International Film Festival is awarding the American actor Willem Defoe with an Honorary Golden Bear in recognition of his career featuring over 100 performances and spanning nearly 40 years since his 1981 debut in Kathryn Bigelow’s debut drama The Loveless. His enormous technical range as an actor extends all the way from the personification of the unfathomably evil to the portrayal of Jesus of Nazareth. In addition to his celebrated cinematic appearances, Dafoe has also pursued a parallel career in theatre, his other passion. Born in Wisconsin in 1955, Willem Dafoe began studying theatre formally at the age of 17. In 1977, he was one of the founding members of the renowned New York theatre ensemble “The Wooster Group”, where he remained a member for several decades. In addition to his activities on stage, Dafoe increasingly began to turn his attention to film work starting in the early 1980s. Walter’s Hill’s Streets of Fire (1984) was soon followed by William Friedkin’s police thriller To Live and Die in L.A. (1985) where he played ruthless counterfeiter Eric “Ric” Masters, a villain who will stop at nothing to rival his adversaries.

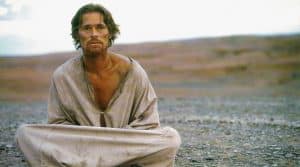

Born in Wisconsin in 1955, Willem Dafoe began studying theatre formally at the age of 17. In 1977, he was one of the founding members of the renowned New York theatre ensemble “The Wooster Group”, where he remained a member for several decades. In addition to his activities on stage, Dafoe increasingly began to turn his attention to film work starting in the early 1980s. Walter’s Hill’s Streets of Fire (1984) was soon followed by William Friedkin’s police thriller To Live and Die in L.A. (1985) where he played ruthless counterfeiter Eric “Ric” Masters, a villain who will stop at nothing to rival his adversaries. In 1986, Dafoe’s portrayal of Sergeant Elias Grodin in Oliver Stone’s anti-war drama Platoon would expose him to a wider audience. He received his first Academy Award nomination for his performance in the break-through film. Two years later, Martin Scorsese successfully recruited him to fill the leading role as Jesus Christ in his hotly debated literary adaptation The Last Temptation of Christ (1988). Still in the same year, Dafoe co-starred alongside Gene Hackman in director Alan Parker’s civil-rights-era drama Mississippi Burning (1988) (right). In the film, Dafoe plays a young FBI agent fighting against racism and the Ku Klux Klan.

In 1986, Dafoe’s portrayal of Sergeant Elias Grodin in Oliver Stone’s anti-war drama Platoon would expose him to a wider audience. He received his first Academy Award nomination for his performance in the break-through film. Two years later, Martin Scorsese successfully recruited him to fill the leading role as Jesus Christ in his hotly debated literary adaptation The Last Temptation of Christ (1988). Still in the same year, Dafoe co-starred alongside Gene Hackman in director Alan Parker’s civil-rights-era drama Mississippi Burning (1988) (right). In the film, Dafoe plays a young FBI agent fighting against racism and the Ku Klux Klan. Many multifaceted roles would follow, in films such as Born on the Fourth of July (1989), Wim Wenders’ In weiter Ferne, so nah! (Faraway, So Close! 1993) and The English Patient (1996). In the year 2000, Dafoe shined as Max Schreck in the horror film Shadow of the Vampire by director E. Elias Merhige. His brilliant turn as a member of the undead earned him his second Academy Award nomination.

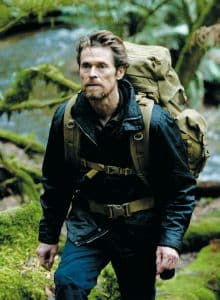

Many multifaceted roles would follow, in films such as Born on the Fourth of July (1989), Wim Wenders’ In weiter Ferne, so nah! (Faraway, So Close! 1993) and The English Patient (1996). In the year 2000, Dafoe shined as Max Schreck in the horror film Shadow of the Vampire by director E. Elias Merhige. His brilliant turn as a member of the undead earned him his second Academy Award nomination. In 2009 Danish director Lars von Trier cast him as the male lead alongside Charlotte Gainsbourg in his psycho-thriller Antichrist – the film became the subject of controversy due to scenes featuring graphic sex and violence. In 2011 Dafoe put on an extraordinary acting performance once again as a lonely hunter in Daniel Nettheim’s thriller The Hunter. Three years later, in Abel Ferrara’s biopic (right) Pasolini Dafoe portrayed the Italian filmmaker in the final period of his life, shortly before his murder.

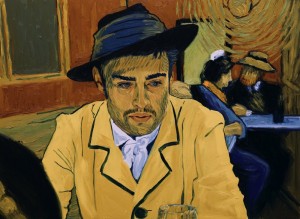

In 2009 Danish director Lars von Trier cast him as the male lead alongside Charlotte Gainsbourg in his psycho-thriller Antichrist – the film became the subject of controversy due to scenes featuring graphic sex and violence. In 2011 Dafoe put on an extraordinary acting performance once again as a lonely hunter in Daniel Nettheim’s thriller The Hunter. Three years later, in Abel Ferrara’s biopic (right) Pasolini Dafoe portrayed the Italian filmmaker in the final period of his life, shortly before his murder. Last year Dafoe has appeared in Kenneth Branagh’s feature Murder on the Orient Express (2017). The German-American joint effort The Sleeping Shepherd (directed by Frank Hudec) is currently in pre-production. He has also finished filming under the direction of Julian Schnabel for At Eternity’s Gate, in which he plays Vincent van Gogh. Dafoe’s role in The Florida Project earned him both a nomination for the British BAFTA Awards and recently his third nomination for an Academy Award, in the category of Best Supporting Actor.

Last year Dafoe has appeared in Kenneth Branagh’s feature Murder on the Orient Express (2017). The German-American joint effort The Sleeping Shepherd (directed by Frank Hudec) is currently in pre-production. He has also finished filming under the direction of Julian Schnabel for At Eternity’s Gate, in which he plays Vincent van Gogh. Dafoe’s role in The Florida Project earned him both a nomination for the British BAFTA Awards and recently his third nomination for an Academy Award, in the category of Best Supporting Actor.

7 Days in Entebbe | USA/UK |

7 Days in Entebbe | USA/UK | Ága | Bulgaria/Ger/France

Ága | Bulgaria/Ger/France

Museo (Museum) | Mex | Dir Alonso Ruizpalacios (Güeros)

Museo (Museum) | Mex | Dir Alonso Ruizpalacios (Güeros) Unsane | USA

Unsane | USA 3 Tage in Quiberon 3 DAYS IN QUIBERON

3 Tage in Quiberon 3 DAYS IN QUIBERON  Black 47

Black 47  Damsel

Damsel  Eldorado – Documentary

Eldorado – Documentary Las herederas (The Heiresses)

Las herederas (The Heiresses) Khook (Pig)

Khook (Pig) La prière (The Prayer)

La prière (The Prayer) Touch Me Not

Touch Me Not Transit

Transit Don’t Worry, He Won’t Get Far on Foot USA

Don’t Worry, He Won’t Get Far on Foot USA Dovlatov | Russian Federation / Poland / Serbia | World Premiere | Director: Alexey German Jr. (Paper Soldier, Under Electric Clouds | With Milan Maric, Danila Kozlovsky, Helena Sujecka, Artur Beschastny, Elena Lyadova

Dovlatov | Russian Federation / Poland / Serbia | World Premiere | Director: Alexey German Jr. (Paper Soldier, Under Electric Clouds | With Milan Maric, Danila Kozlovsky, Helena Sujecka, Artur Beschastny, Elena Lyadova Eva | France | World Premiere | Director: Benoit Jacquot (Three Hearts, Diary of a Chambermaid) | With Isabelle Huppert, Gaspard Ulliel, Julia Roy, Richard Berry

Eva | France | World Premiere | Director: Benoit Jacquot (Three Hearts, Diary of a Chambermaid) | With Isabelle Huppert, Gaspard Ulliel, Julia Roy, Richard Berry Figlia mia (Daughter of Mine) | Italy / Germany / Switzerland | Director: Laura Bispuri (Sworn Virgin) With Valeria Golino, Alba Rohrwacher, Sara Casu, Udo Kier | World premiere

Figlia mia (Daughter of Mine) | Italy / Germany / Switzerland | Director: Laura Bispuri (Sworn Virgin) With Valeria Golino, Alba Rohrwacher, Sara Casu, Udo Kier | World premiere In den Gängen (In the Aisles) | Germany | World Premiere | Director: Thomas Stuber (Teenage Angst, A Heavy Heart) | With Franz Rogowski, Sandra Hüller, Peter Kurth

In den Gängen (In the Aisles) | Germany | World Premiere | Director: Thomas Stuber (Teenage Angst, A Heavy Heart) | With Franz Rogowski, Sandra Hüller, Peter Kurth Twarz (Mug) | Poland | Director: Małgorzata Szumowska (In the Name of, Body) | World Premiere | With Mateusz Kościukiewicz, Agnieszka Podsiadlik, Małgorzata Gorol, Roman Gancarczyk, Dariusz Chojnacki, Robert Talarczyk, Anna Tomaszewska, Martyna Krzysztofik

Twarz (Mug) | Poland | Director: Małgorzata Szumowska (In the Name of, Body) | World Premiere | With Mateusz Kościukiewicz, Agnieszka Podsiadlik, Małgorzata Gorol, Roman Gancarczyk, Dariusz Chojnacki, Robert Talarczyk, Anna Tomaszewska, Martyna Krzysztofik The Bookshop | Spain / United Kingdom / Germany Premiere | Director: Isabel Coixet (Things I Never Told You, My Life Without Me, The Secret Life of Words | With Emily Mortimer, Bill Nighy, Patricia Clarkson

The Bookshop | Spain / United Kingdom / Germany Premiere | Director: Isabel Coixet (Things I Never Told You, My Life Without Me, The Secret Life of Words | With Emily Mortimer, Bill Nighy, Patricia Clarkson Das schweigende Klassenzimmer (The Silent Revolution) | Germany | Word Premiere | Director: Lars Kraume (The People vs. Fritz Bauer) | With Leonard Scheicher, Tom Gramenz, Lena Klenke, Jonas Dassler, Florian Lukas, Jördis Triebel, Michael Gwisdek, Ronald Zehrfeld, Burghart Klaußner

Das schweigende Klassenzimmer (The Silent Revolution) | Germany | Word Premiere | Director: Lars Kraume (The People vs. Fritz Bauer) | With Leonard Scheicher, Tom Gramenz, Lena Klenke, Jonas Dassler, Florian Lukas, Jördis Triebel, Michael Gwisdek, Ronald Zehrfeld, Burghart Klaußner Gurrumul – Documentary

Gurrumul – Documentary The 22nd edition of the London Human Rights Watch Film Festival opens in time for

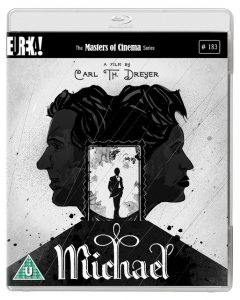

The 22nd edition of the London Human Rights Watch Film Festival opens in time for  Dir: Carl Theodor Dreyer | Writer: Thea von Harbou | Silent | 90′

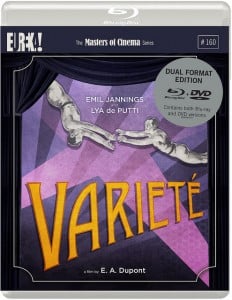

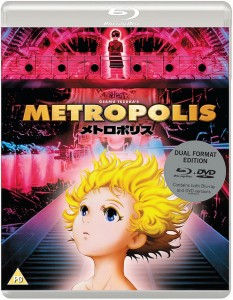

Dir: Carl Theodor Dreyer | Writer: Thea von Harbou | Silent | 90′ Filmed on a magnificent studio set, and in intimate close-ups where the characters often appear as if in a halo, silhouetted against the mysterious darkness, the piano accompaniment lends a sinister almost ghostly tension to the story. The meticulous camera moves with stealth drawing us in to the intrigue while maintaining an unsettling distance. Passion glows but never sizzles in Rudolph Mate and Karl Freund’s cinematography, Freund has his only role as an actor, in vignette, as an jovial art dealer. The film was scripted by Dreyer with Fritz Lang’s wife, Thea von Harbou (Metropolis, M), based on Herman Bang’s 1902 novel

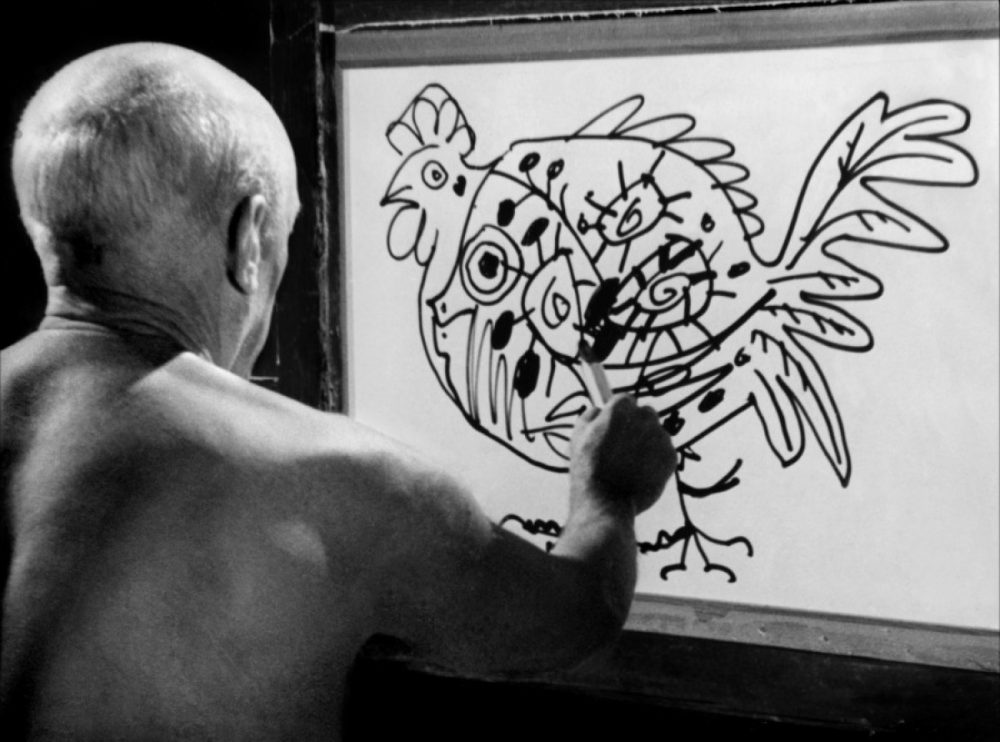

Filmed on a magnificent studio set, and in intimate close-ups where the characters often appear as if in a halo, silhouetted against the mysterious darkness, the piano accompaniment lends a sinister almost ghostly tension to the story. The meticulous camera moves with stealth drawing us in to the intrigue while maintaining an unsettling distance. Passion glows but never sizzles in Rudolph Mate and Karl Freund’s cinematography, Freund has his only role as an actor, in vignette, as an jovial art dealer. The film was scripted by Dreyer with Fritz Lang’s wife, Thea von Harbou (Metropolis, M), based on Herman Bang’s 1902 novel Dir: Dorota Kobiela, Hugh Welchman | With Douglas Booth, Jerome Flynn, Robert Gulaczyk, Helen McCrory, John Sessions, Eleanor Tomlinson, Aidan Turner, Chris O’Dowd | Animated Biography | Poland | UK | 94′

Dir: Dorota Kobiela, Hugh Welchman | With Douglas Booth, Jerome Flynn, Robert Gulaczyk, Helen McCrory, John Sessions, Eleanor Tomlinson, Aidan Turner, Chris O’Dowd | Animated Biography | Poland | UK | 94′

s such as The Seventh Seal (1957) and Wild Strawberries(1957), and ground-breaking TV series like Scenes From a Marriage (1973) to lesser known titles, and those scripted by Bergman and directed by his collaborators. All in all more than 50 films directed or written by Bergman, as well as several TV series, will screen at the BFI accompanied by an ambitious events programme, designed to bring Bergman and his work to life for a new generation. This will include discussions, immersive experiences and talent-led events.

s such as The Seventh Seal (1957) and Wild Strawberries(1957), and ground-breaking TV series like Scenes From a Marriage (1973) to lesser known titles, and those scripted by Bergman and directed by his collaborators. All in all more than 50 films directed or written by Bergman, as well as several TV series, will screen at the BFI accompanied by an ambitious events programme, designed to bring Bergman and his work to life for a new generation. This will include discussions, immersive experiences and talent-led events.

Dir.: Aditya Vikram Sengupta; Cast: Lolita Chatterjee, Ratnabali Bhattacharjee, Sumanto Chattopadhyay, Jim Sarbh; India/France/Singapore 2018, 97’.

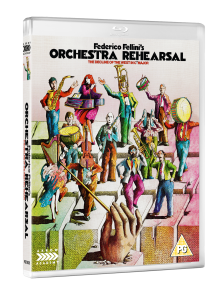

Dir.: Aditya Vikram Sengupta; Cast: Lolita Chatterjee, Ratnabali Bhattacharjee, Sumanto Chattopadhyay, Jim Sarbh; India/France/Singapore 2018, 97’. Dir.: Federico Fellini; Cast: Baldwin Baas, Elisabeth Labi; Italy/West Germany | 70′.

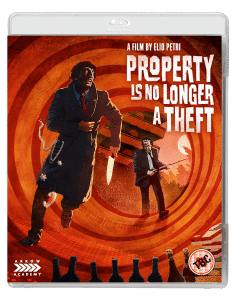

Dir.: Federico Fellini; Cast: Baldwin Baas, Elisabeth Labi; Italy/West Germany | 70′. Dir: Elio Petri | Writer: Ugo Pirri | Cast: Ugo Tognazzi, Flavio Bucci, Daria Nicolodi | Italy | Comedy Drama 126′

Dir: Elio Petri | Writer: Ugo Pirri | Cast: Ugo Tognazzi, Flavio Bucci, Daria Nicolodi | Italy | Comedy Drama 126′

Dir.: Francis Lee; Cast: Josh O’Connor, Alec Secareanu, Gemma Jones, Ian Hart; UK 2017, 104 min.

Dir.: Francis Lee; Cast: Josh O’Connor, Alec Secareanu, Gemma Jones, Ian Hart; UK 2017, 104 min.

Wim Wenders’ prize-winning classic Der Himmel über Berlin (Wings of Desire, Federal Republic of Germany / France 1987) returns to the screen in a new, digitally restored 4K DCP version. Two guardian angels keep watch over Berlin, until one of them falls in love with a mortal woman. He chooses to become human, giving up his immortality, and an entirely new world is revealed to him. The film was shot on both black-and-white and colour stock. At the time, that required several additional steps in the lab in order to produce a final colour negative, which was several generations removed from the camera negatives. This version, restored by the Wim Wenders Foundation, is based on the original negatives;

Wim Wenders’ prize-winning classic Der Himmel über Berlin (Wings of Desire, Federal Republic of Germany / France 1987) returns to the screen in a new, digitally restored 4K DCP version. Two guardian angels keep watch over Berlin, until one of them falls in love with a mortal woman. He chooses to become human, giving up his immortality, and an entirely new world is revealed to him. The film was shot on both black-and-white and colour stock. At the time, that required several additional steps in the lab in order to produce a final colour negative, which was several generations removed from the camera negatives. This version, restored by the Wim Wenders Foundation, is based on the original negatives; Az én XX. századom (My 20th Century, Hungary / Federal Republic of Germany 1989), the feature debut of the winner of the 2017 Golden Bear, Ildikó Enyedi, is a complex, poetic fairy tale, and an homage to silent movies. Shot in black-and-white, the film follows the very different live of identical twins in Old Europe at the dawn of the 20th century. Using the original camera negative and the magnetic sound track, the film was digitally restored in 4K by the Hungarian National Film Fund – Hungarian National Film Archive, working with Hungarian Filmlab. Cinematographer Tibor Máthé (HSC – Hungarian Society of Cinematographers) supervised the digital grading.

Az én XX. századom (My 20th Century, Hungary / Federal Republic of Germany 1989), the feature debut of the winner of the 2017 Golden Bear, Ildikó Enyedi, is a complex, poetic fairy tale, and an homage to silent movies. Shot in black-and-white, the film follows the very different live of identical twins in Old Europe at the dawn of the 20th century. Using the original camera negative and the magnetic sound track, the film was digitally restored in 4K by the Hungarian National Film Fund – Hungarian National Film Archive, working with Hungarian Filmlab. Cinematographer Tibor Máthé (HSC – Hungarian Society of Cinematographers) supervised the digital grading. Source: Sony Pictures Entertainment, © Columbia Pictures Corporation Inc.

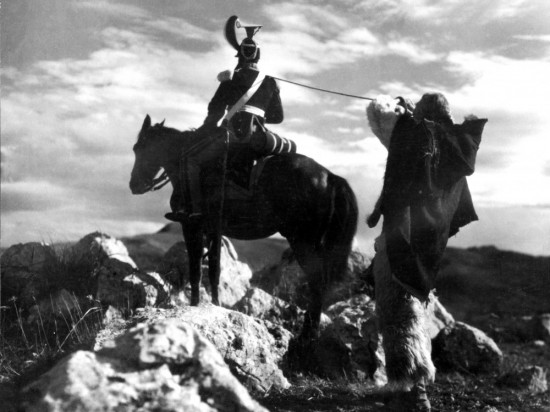

Source: Sony Pictures Entertainment, © Columbia Pictures Corporation Inc. Letyat Zhuravli (The Cranes Are Flying, USSR 1957) by Mikhail Kalatozov was Soviet cinema’s first international hit after World War II. Made during the period of liberalisation that followed Joseph Stalin’s death, this unusual black-and-white film’s expressionist images tell the tragic story of two lovers after Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union. The film brought international fame to Mikhail Kalatozov and his lead actress, Tatiana Samoilova. Letyat Zhuravli was restored by Mosfilm under the leadership of general director Karen Shakhnazarov. The ditigal 2K restoration, on the basis of the original negative, was supervised by the head of restoration Igor Bogdasarov.

Letyat Zhuravli (The Cranes Are Flying, USSR 1957) by Mikhail Kalatozov was Soviet cinema’s first international hit after World War II. Made during the period of liberalisation that followed Joseph Stalin’s death, this unusual black-and-white film’s expressionist images tell the tragic story of two lovers after Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union. The film brought international fame to Mikhail Kalatozov and his lead actress, Tatiana Samoilova. Letyat Zhuravli was restored by Mosfilm under the leadership of general director Karen Shakhnazarov. The ditigal 2K restoration, on the basis of the original negative, was supervised by the head of restoration Igor Bogdasarov. With Tokyo Boshoku (Tokyo Twilight, Japan 1957), Berlinale Classics will provide a rare opportunity to see a largely unknown and seldom shown work by Yasujiro Ozu. The theme of the end of a family living together is one that Japanese directing maestro Yasujiro Ozu often reworks, and here he has given it a dramatic twist. In wintery Tokyo, a family’s silence leads to its breakdown. Tokyo Boshoku, considered Ozu’s most sombre post-war film, was digitally restored in 4K on the basis of the 35mm duplicate negative provided by the Japanese production company Shochiku, managed by Shochiku MediaWorX Inc. Colour correction was led by Ozu’s former assistant cameraman Takashi Kawamata and cinematographer Masashi Chikamori.

With Tokyo Boshoku (Tokyo Twilight, Japan 1957), Berlinale Classics will provide a rare opportunity to see a largely unknown and seldom shown work by Yasujiro Ozu. The theme of the end of a family living together is one that Japanese directing maestro Yasujiro Ozu often reworks, and here he has given it a dramatic twist. In wintery Tokyo, a family’s silence leads to its breakdown. Tokyo Boshoku, considered Ozu’s most sombre post-war film, was digitally restored in 4K on the basis of the 35mm duplicate negative provided by the Japanese production company Shochiku, managed by Shochiku MediaWorX Inc. Colour correction was led by Ozu’s former assistant cameraman Takashi Kawamata and cinematographer Masashi Chikamori. The Berlinale Classics section will open on February 16, 2018, at 5 pm in the Friedrichstadt-Palast with the premiere of the Deutsche Kinemathek’s digital restoration of the 1923 silent film classic Das alte Gesetz (The Ancient Law) directed by E.A. Dupont. ZDF/ARTE commissioned French composer Philippe Schoeller to create new music for this version, which will be presented by the Orchester Jakobsplatz München with Daniel Grossmann at the podium.

The Berlinale Classics section will open on February 16, 2018, at 5 pm in the Friedrichstadt-Palast with the premiere of the Deutsche Kinemathek’s digital restoration of the 1923 silent film classic Das alte Gesetz (The Ancient Law) directed by E.A. Dupont. ZDF/ARTE commissioned French composer Philippe Schoeller to create new music for this version, which will be presented by the Orchester Jakobsplatz München with Daniel Grossmann at the podium. French directing duo Alexandre Bustillo and Julien Maury, who rose to fame with their standout debut Inside, have done their best to give an arthouse twist to Tobe Hooper’s 1974 cult original TCM replacing his pared-down grainy indie look with a grungy green-sheened shocker, blunting facial features and darkening scenes of gory violence and misogyny. It’s a tolerably decent adaptation which echoes Malick’s Badlands.

French directing duo Alexandre Bustillo and Julien Maury, who rose to fame with their standout debut Inside, have done their best to give an arthouse twist to Tobe Hooper’s 1974 cult original TCM replacing his pared-down grainy indie look with a grungy green-sheened shocker, blunting facial features and darkening scenes of gory violence and misogyny. It’s a tolerably decent adaptation which echoes Malick’s Badlands. Dir: Anthony Kimmins | Writer: Nigel Balchin | Psychological Drama | UK | Burgess Meredith, Barbara White, Kieron Moore, Dulcie Gray

Dir: Anthony Kimmins | Writer: Nigel Balchin | Psychological Drama | UK | Burgess Meredith, Barbara White, Kieron Moore, Dulcie Gray Hollywood may still be struggling with female representation as 2018 gets underway, but Europe has seen tremendous successes in the world of indie film where talented women of all ages are winning accolades in every sphere of the film industry, bringing their unique vision and intuition to a party that has continued to rock throughout the past year. Admittedly, there have been some really fabulous female roles recently – probably more so than for male actors. But on the other side of the camera, women have also created some thumping dramas; robust documentaries and bracingly refreshing genre outings: Lucrecia Martel’s mesmerising Argentinian historical fantasy ZAMA (LFF/left) and Julia Ducournau’s Belgo-French horror drama RAW (below/right) have been amongst the most outstanding features in recent memory. All these films provide great insight into the challenges women continue to face, both personally and in society as a whole, and do so without resorting to worthiness or sentimentality. So as we go forward into another year, here’s a flavour of what’s been happening in 2017.

Hollywood may still be struggling with female representation as 2018 gets underway, but Europe has seen tremendous successes in the world of indie film where talented women of all ages are winning accolades in every sphere of the film industry, bringing their unique vision and intuition to a party that has continued to rock throughout the past year. Admittedly, there have been some really fabulous female roles recently – probably more so than for male actors. But on the other side of the camera, women have also created some thumping dramas; robust documentaries and bracingly refreshing genre outings: Lucrecia Martel’s mesmerising Argentinian historical fantasy ZAMA (LFF/left) and Julia Ducournau’s Belgo-French horror drama RAW (below/right) have been amongst the most outstanding features in recent memory. All these films provide great insight into the challenges women continue to face, both personally and in society as a whole, and do so without resorting to worthiness or sentimentality. So as we go forward into another year, here’s a flavour of what’s been happening in 2017. It all started at SUNDANCE in January where documentarian Pascale Lamche’s engrossing film about Winnie Mandela, WINNIE, won Best World Doc and Maggie Betts was awarded a directing prize for her debut feature NOVITIATE, about a nun struggling to take and keep her vows in 1960s Rome. Eliza Hitman also bagged the coveted directing award for her gay-themed indie drama BEACH RATS, that looks at addiction from a young boy’s perspective.

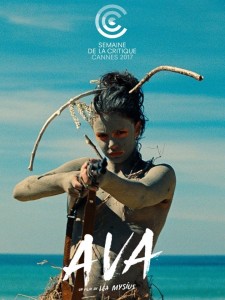

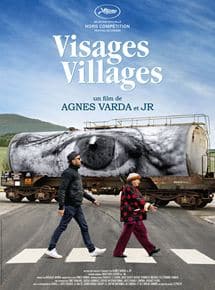

It all started at SUNDANCE in January where documentarian Pascale Lamche’s engrossing film about Winnie Mandela, WINNIE, won Best World Doc and Maggie Betts was awarded a directing prize for her debut feature NOVITIATE, about a nun struggling to take and keep her vows in 1960s Rome. Eliza Hitman also bagged the coveted directing award for her gay-themed indie drama BEACH RATS, that looks at addiction from a young boy’s perspective. Meanwhile, back in Europe, BERLIN‘s Golden Bear went to Hungarian filmmaker Ildiko Enyedi (right) for her thoughtful and inventive exploration of adult loneliness and alienation BODY AND SOUL. Agnieska Holland won a Silver Bear for her green eco feature SPOOR, and Catalan newcomer Carla Simón went home with a prize for her feature debut SUMMER 1993 tackling the more surprising aspects of life for an orphaned child who goes to live with her cousins. CANNES 2017, the festival’s 70th celebration, also proved to be another strong year for female talent. Claire Simon’s first comedy – looking at love in later life – LET THE SUNSHINE IN was well-received and provided a playful role for Juliette Binoche, which she performed with gusto. Agnès Varda’s entertaining travel piece FACES PLACES took us all round France and finally showed Jean-Luc Godard’s true colours, winning awards at TIFF and Cannes. Newcomers were awarded in the shape of Léa Mysius whose AVA won the SACD prize for its tender exploration of oncoming blindness, and Léonor Séraille whose touching drama about the after-effects of romantic abandonment MONTPARNASSE RENDEZVOUS won the Caméra D’Or.

Meanwhile, back in Europe, BERLIN‘s Golden Bear went to Hungarian filmmaker Ildiko Enyedi (right) for her thoughtful and inventive exploration of adult loneliness and alienation BODY AND SOUL. Agnieska Holland won a Silver Bear for her green eco feature SPOOR, and Catalan newcomer Carla Simón went home with a prize for her feature debut SUMMER 1993 tackling the more surprising aspects of life for an orphaned child who goes to live with her cousins. CANNES 2017, the festival’s 70th celebration, also proved to be another strong year for female talent. Claire Simon’s first comedy – looking at love in later life – LET THE SUNSHINE IN was well-received and provided a playful role for Juliette Binoche, which she performed with gusto. Agnès Varda’s entertaining travel piece FACES PLACES took us all round France and finally showed Jean-Luc Godard’s true colours, winning awards at TIFF and Cannes. Newcomers were awarded in the shape of Léa Mysius whose AVA won the SACD prize for its tender exploration of oncoming blindness, and Léonor Séraille whose touching drama about the after-effects of romantic abandonment MONTPARNASSE RENDEZVOUS won the Caméra D’Or. The Doyenne of French contemporary cinema Isabelle Huppert won Best Actress in LOCARNO 2017 for her performance as a woman who morphs from a meek soul to a force to be reckoned with when she is struck by lightening, in Serge Bozon’s dark comedy MADAME HYDE. Huppert has been winning accolades since the 1970s but she still has to challenge Hollywood’s Ann Doran (1911-2000) on film credits (374) – but there is plenty of time!). Meanwhile, Nastassja Kinski was awarded a Lifetime Achievement Honour for her extensive and eclectic contribution to World cinema (Paris,Texas, Inland Empire, Cat People and Tess to name a few).

The Doyenne of French contemporary cinema Isabelle Huppert won Best Actress in LOCARNO 2017 for her performance as a woman who morphs from a meek soul to a force to be reckoned with when she is struck by lightening, in Serge Bozon’s dark comedy MADAME HYDE. Huppert has been winning accolades since the 1970s but she still has to challenge Hollywood’s Ann Doran (1911-2000) on film credits (374) – but there is plenty of time!). Meanwhile, Nastassja Kinski was awarded a Lifetime Achievement Honour for her extensive and eclectic contribution to World cinema (Paris,Texas, Inland Empire, Cat People and Tess to name a few). With a Jury headed by Annette Bening, VENICE again showed women in a strong light. Away from the Hollywood-fraught main competition, this year’s Orizzonti Award was awarded to Susanna Nicchiarelli’s NICO, 1988, a stunning biopic of the final years of the renowned model and musician Christa Pfaffen, played by a feisty Trine Dyrholm. And Sara Forestier’s Venice Days winning debut M showed how a stuttering girl and her illiterate boyfriend help each other overcome adversity. Charlotte Rampling won the prize for Best Actress for her portrait of strength in the face of her husbands’ imprisonment in Andrea Pallaoro’s HANNAH.

With a Jury headed by Annette Bening, VENICE again showed women in a strong light. Away from the Hollywood-fraught main competition, this year’s Orizzonti Award was awarded to Susanna Nicchiarelli’s NICO, 1988, a stunning biopic of the final years of the renowned model and musician Christa Pfaffen, played by a feisty Trine Dyrholm. And Sara Forestier’s Venice Days winning debut M showed how a stuttering girl and her illiterate boyfriend help each other overcome adversity. Charlotte Rampling won the prize for Best Actress for her portrait of strength in the face of her husbands’ imprisonment in Andrea Pallaoro’s HANNAH.  At last but not least, Hong Kong director Vivianne Qu (left/LFF) was awarded the Fei Mei prize at PINGYAO’s inaugural CROUCHING TIGER, HIDDEN DRAGON film festival and the Film Festival of India’s Silver Peacock for her delicately charming feature ANGELS WEAR WHITE that deftly raises the harrowing plight of women facing sexual abuse in the mainland. It seems that this is a hot potato the superpowers of China and US still have in common. But on a positive note, LADYBIRD Greta Gerwig’s first film as a writer and director, has been sweeping the boards critically all over the US and is the buzzworthy comedy drama of 2018 (coming in February). So that’s something else to look forward to. MT

At last but not least, Hong Kong director Vivianne Qu (left/LFF) was awarded the Fei Mei prize at PINGYAO’s inaugural CROUCHING TIGER, HIDDEN DRAGON film festival and the Film Festival of India’s Silver Peacock for her delicately charming feature ANGELS WEAR WHITE that deftly raises the harrowing plight of women facing sexual abuse in the mainland. It seems that this is a hot potato the superpowers of China and US still have in common. But on a positive note, LADYBIRD Greta Gerwig’s first film as a writer and director, has been sweeping the boards critically all over the US and is the buzzworthy comedy drama of 2018 (coming in February). So that’s something else to look forward to. MT

Danish director Carl-Theodor Dreyer (Ordet) is known for his austere and minimalist features.

Danish director Carl-Theodor Dreyer (Ordet) is known for his austere and minimalist features.

Last year’s Generation strand featured some really hot titles, proving that youth cinema is capable of surprising and entertaining the older generation – not just its key audience. In its 41st edition, Generation reinforces its reputation for presenting ambitious new discoveries in the international contemporary film scene to young people told at eye level.

Last year’s Generation strand featured some really hot titles, proving that youth cinema is capable of surprising and entertaining the older generation – not just its key audience. In its 41st edition, Generation reinforces its reputation for presenting ambitious new discoveries in the international contemporary film scene to young people told at eye level.

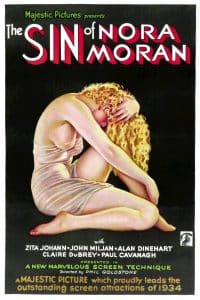

Dir: Phil Goldstone | Writer: Frances Hyland from the play by Willis Maxwell Goodhue | Cast: Zita Johann, Alan Dinehart, Paul Cavanagh, Claire DuBrey, John Miljan, Henry B. Walthall, Cora Sue Collins | USA / Drama / 65 min

Dir: Phil Goldstone | Writer: Frances Hyland from the play by Willis Maxwell Goodhue | Cast: Zita Johann, Alan Dinehart, Paul Cavanagh, Claire DuBrey, John Miljan, Henry B. Walthall, Cora Sue Collins | USA / Drama / 65 min US DRAMA –

US DRAMA – Filmmaker Maren Ade has created one of the most poignant and refreshingly humorous German arthouse comedy dramas of recent memory – it never drags despite its three-hour running time. Picturing the absurd and often awkward nature of family relationships, this is a life-affirming experience not to be missed, especially at Christmas time. After The Forest for the Trees and Everyone Else, Ade is working her way slowly but surely to the top as most of the most refreshing European writer directors around..