2021 gets off to a lowkey start with Sundance film festival announcing a mostly virtual edition, along with Rotterdam that follows in its footsteps on February 7th.

Sundance welcomes fewer features to this year’s line-up with 72 feature films as apposed to last year’s 118, but nearly half are female directed and 15% from the LGBTQ+ community.

Themes of retreat, regeneration and renewal are the touchstones to this year’s programme and this seems entirely appropriate given our global experience since March 2020. The world has taken stock of itself but not necessarily come up with the answers. Many film festivals are congratulating themselves for ‘increased attendance record’ with a boost from their online community. Watching films, and attending festivals online works as a complementary form of entertainment in extremis, but make no mistake, the vast majority of viewers still prefer the buzz of the festival experience and the human element that it brings.

As we stand of the brink of 2021 most of us are experiencing some sense of disconnection with our previous existence, and Robin Wright echoes this sentiment in her directorial debut, in which she also stars ,as a woman who seeks a life off grid after bereavement. Very much in the same vein as the Venice 2020 triumph Nomadland, Wright’s film Land is one of the most apposite and buzz-worthy films in the premiere lineup at this year’s Utah festival.

Sundance Institute founder and president Robert Redford is deeply aware of this social and emotional disenfranchisement and comments “Togetherness has been an animating principle here at the Sundance Institute as we’ve worked to reimagine the festival for 2021, because there is no Sundance without our community,”

And this sentiment resonates through the competition line-up. with other narrative features directly alluding to the tragedy that has affected, possibly more than we realise going forward.

A list of films confirmed for the 2021 Sundance Film Festival are as follows.

World Cinema Dramatic Competition

The Dog Who Wouldn’t Be Quiet | Argentina (Dir: Ana Katz, writers: Ana Katz, Gonzalo Delgado | World Premiere

Sebastian, a man in his 30s, works a series of temporary jobs and he embraces love at every opportunity. He transforms, through a series of short encounters, as the world flirts with possible apocalypse. Cast: Daniel Katz, Julieta Zylberberg, Valeria Lois, Mirella Pascual, Carlos Portaluppi.

Passing / UK/US (Dir/wri: Rebecca Hall | World Premiere

Based on the 19th century novel by Chicago born writer Nella Larsen, this first feature for Rebecca Hall sees two high old school friends reunited in a mutual obsession that threatens both of their carefully constructed realities.

El Planeta / US/Spain (Dir/Wri Amalia Ulman | World Premiere

Amid the devastation of post-crisis Spain, mother and daughter bluff and grift to keep up the lifestyle they think they deserve, bonding over common tragedy and an impending eviction. Cast: Amalia Ulman, Ale Ulman, Nacho Vigalondo, Zhou Chen, Saoirse Bertram.

Fire in the Mountains / India (Dir/Wri: Ajitpal Singh | World Premiere

A mother toils to save money to build a road in a Himalayan village to take her wheelchair-bound son for physiotherapy, but her husband, who believes that an expensive religious ritual is the remedy, steals her savings. Cast: Vinamrata Rai, Chandan Bisht, Mayank Singh Jaira, Harshita Tewari, Sonal Jha.

Hive / Kos, Switzerland, Macedonia, Albania (Dir/Wri: Blerta Basholli | World Premiere

Fahrije’s husband has been missing since the war in Kosovo. She sets up her own small business to provide for her kids, but as she fights against a patriarchal society that does not support her, she faces a crucial decision: to wait for his return, or to continue to persevere. Cast: Yllka Gashi, Çun Lajçi, Aurita Agushi, Kumrije Hoxha, Adriana Matoshi, Kaona Sylejmani.

Human Factors / Ger, Italy, Denmark (Dir/Wri: Ronny Trocker | World Premiere

A mysterious housebreaking exposes the agony of an exemplary middle-class family. Cast: Sabine Timoteo, Mark Waschke, Jule Hermann, Wanja Valentin Kube, Hannes Perkmann, Daniel Séjourné.

Luzzu / Malta (Dir/Wri): Alex Camilleri | World Premiere

Jesmark, a struggling fisherman on the island of Malta, is forced to turn his back on generations of tradition and risk everything by entering the world of black-market fishing to provide for his girlfriend and newborn baby. Cast: Jesmark Scicluna, Michela Farrugia, David Scicluna.

One for the Road / China,Hong Kong, Thailand (Dir: Baz Poonpiriya, Wri: Baz Poonpiriya, Nottapon Boonprakob, Puangsoi Aksornsawang, Wong Kar Wai) | World Premiere

Boss is a consummate ladies’ man, a free spirit and a bar owner in NYC. One day, he gets a surprise call from Aood, an estranged friend who has returned home to Thailand. Dying of cancer, Aood enlists Boss’ help to complete a bucket list — but both are hiding something. Cast: Tor Thanapob, Ice Natara, Violette Wautier, Aokbab Chutimon, Ploi Horwang, Noon Siraphun.

The Pink Cloud / Brazil (Dir/Wri: Iuli Gerbase, | World Premiere

A mysterious and deadly pink cloud appears across the globe, forcing everyone to stay home. Strangers at the outset, Giovana and Yago try to invent themselves as a couple as years of shared lockdown pass. While Yago is living in his own utopia, Giovana feels trapped deep inside. Cast: Renata de Lélis, Eduardo Mendonça.

Pleasure / Swed/Neth/France (Dir,Wri: Ninja Thyberg | World Prem

A 20-year-old girl moves from her small town in Sweden to L.A. for a shot at a career in the adult film industry. Cast: Sofia Kappel, Revika Anne Reustle, Evelyn Claire, Chris Cock, Dana DeArmond, Kendra Spade.

Prime Time / Poland (Dir: Jakub Piątek, Writers: Jakub Piątek, Lukasz Czapski | World Premierę

On the last day of 1999, 20-year-old Sebastian locks himself in a TV studio. He has two hostages, a gun and an important message for the world. The story of the attack explores a rebel’s extreme measures and last resort. Cast: Bartosz Bielenia, Magdalena Poplawska, Andrzej Klak, Malgorzata Hajewska-Krzysztofik, Dobromir Dymecki, Monika Frajczyk.

World Cinema Documentary Competition

Faya Dayi / Ethiopia/US (Dir/Wri: Jessica Beshir) | World Premiere

A spiritual journey into the highlands of Harar, immersed in the rituals of khat, a leaf Sufi Muslims chewed for centuries for religious meditations — and Ethiopia’s most lucrative cash crop today. A tapestry of intimate stories offers a window into the dreams of youth under a repressive regime.

Flee / Den/Norway/Sweden/France (Dir Jonas Poher Rasmussen | World Premiere

Amin arrived as an unaccompanied minor in Denmark from Afghanistan. Today, he is a successful academic and is getting married to his longtime boyfriend. A secret he has been hiding for 20 years threatens to ruin the life he has built. W

Inconvenient Indian | Canada (Dir/Wri: Michelle Latimer | International premiere

An examination of Thomas King’s brilliant dismantling of North America’s colonial narrative, which reframes history with the powerful voices of those continuing the tradition of Indigenous resistance.

Misha and the Wolves

United Kingdom, Belgium (Dir/Wri: Sam Hobkinson) | World Premiere

A woman’s Holocaust memoir takes the world by storm, but a fallout with her publisher turned detective reveals her story as an audacious deception created to hide a darker truth.

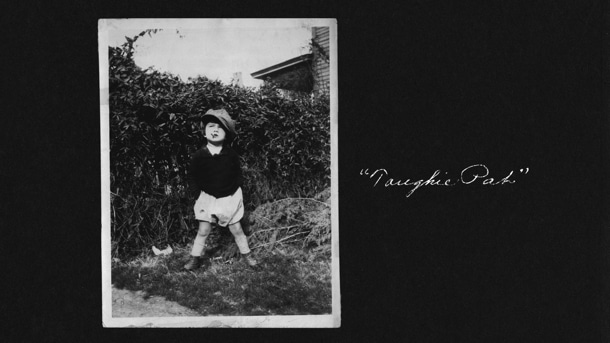

The Most Beautiful Boy in the World / Sweden (Dir: Kristina Lindström, Kristian Petri | World Premiere

Swedish actor/musician Björn Andresen’s life was forever changed at the age of 15, when he played Tadzio, the object of Dirk Bogarde’s obsession in Death in Venice — a role that led Italian maestro Luchino Visconti to dub him “the world’s most beautiful boy.”

Playing With Sharks / Australia (Dir/Wri: Sally Aitken | World Premier

Valerie Taylor is a shark fanatic and an Australian icon — a marine maverick who forged her way as a fearless diver, cinematographer and conservationist. She filmed the real sharks for Jaws and famously wore a chainmail suit, using herself as shark bait, changing our scientific understanding of sharks forever.

President / Denmark/US, Norway (Dir: Camilla Nielsson | World Premiere

Zimbabwe is at a crossroads. The leader of the opposition MDC party, Nelson Chamisa, challenges the old guard ZANU-PF led by Emmerson Mnangagwa, known as “The Crocodile.” The election tests both the ruling party and the opposition — how do they interpret principles of democracy in discourse and in practice?

Sabaya / Sweden (Dir/Wri: Hogir Hirori | World Premiere

With just a mobile phone and a gun, Mahmud, Ziyad and their group risk their lives trying to save Yazidi women and girls being held by ISIS as Sabaya (abducted sex slaves) in the most dangerous camp in the Middle East, Al-Hol in Syria

Taming the Garden / Swit/Ger, Georgia (Dir: Salomé Jashi | World Premiere

A poetic ode to the rivalry between men and nature. World Premiere

Writing With Fire / India (Dir/Wris: Rintu Thomas, Sushmit Ghosh | World Premiere

In a cluttered news landscape dominated by men, emerges India’s only newspaper run by Dalit women. Armed with smartphones, chief reporter Meera and her journalists break traditions on the front lines of India’s biggest issues and within the confines of their own homes, redefining what it means to be powerful.

The Blazing World / U.S.A. (Dir: Carlson Young, Wri: Carlson Young, Pierce Brown | World Premiere

Decades after the accidental drowning of her twin sister, a self-destructive young woman returns to her family home, finding herself drawn to an alternate dimension where her sister may still be alive. Cast: Udo Kier, Carlson Young, Dermot Mulroney, Vinessa Shaw, John Karna, Soko.

Cryptozoo / US (Dir/Wr: Dash Shaw) | World Premiere

As cryptozookeepers struggle to capture a Baku (a legendary dream-eating hybrid creature) they begin to wonder if they should display these rare beasts in the confines of a cryptozoo, or if these mythical creatures should remain hidden and unknown. Cast: Lake Bell, Michael Cera, Angeliki Papoulia, Zoe Kazan, Peter Stormare, Grace Zabriskie

First Date / US. (Dir/Wri: Manuel Crosby, Darren Knapp | World Premiere

Conned into buying a shady ’65 Chrysler, Mike’s first date with the girl next door, Kelsey, implodes as he finds himself targeted by criminals, cops and a crazy cat lady. A night fueled by desire, bullets and burning rubber makes any other first date seem like a walk in the park. Cast: Tyson Brown, Shelby Duclos, Jesse Janzen, Nicole Berry, Ryan Quinn Adams, Brandon Kraus.

Ma Belle, My Beauty / US., France (Dir/Wri: Marion Hill | World Premiere

A surprise reunion in southern France reignites passions and jealousies between two women who were formerly polyamorous lovers. Cast: Idella Johnson, Hannah Pepper, Lucien Guignard, Sivan Noam Shimon.

R#J / US (Dir/Wri Carey William | World Premiere

A reimagining of Romeo and Juliet, taking place through their cellphones, in a mash-up of Shakespearean dialogue with current social media communication. Cast: Camaron Engels, Francesca Noel, David Zayas, Diego Tinoco, Siddiq Saunderson, Russell Hornsby.

Searchers / US. (Dir: Pacho Velez | World Premiere

In encounters alternately humorous and touching, a diverse set of New Yorkers navigate their preferred dating apps in search of their special someone.

Strawberry Mansion / US (Dir/Wri: Albert Birney, Kentucker Audley | World Premiere

In a world where the government records and taxes dreams, an unassuming dream auditor gets swept up in a cosmic journey through the life and dreams of an aging eccentric named Bella. Together, they must find a way back home. Cast: Penny Fuller, Kentucker Audley, Grace Glowicki, Reed Birney, Linas Phillips, Constance Shulman.

We’re All Going to the World’s Fair / US (Dir/Wri: Jane Schoenbrun | World Premiere

A teenage girl becomes immersed in an online role-playing game. Cast: Anna Cobb, Michael J. Rogers.

Amy Tan: Unintended Memoir / US. (Director: James Redford | World Premiere

Amy Tan has established herself as one of America’s most respected literary voices. Born to Chinese immigrant parents, it would be decades before the author of The Joy Luck Club would fully understand the inherited trauma rooted in the legacies of women who survived the Chinese tradition of concubinage.

Bring Your Own Brigade / US. (Dir/wri: Lucy Walker | World Premiere

A character-driven verité and revelatory investigation takes us on a journey embedded with firefighters and residents on a mission to understand the causes of historically large wildfires and how to survive them, discovering that the solution has been here all along.

Eight for Silver / U.S.A., France (Dir/Wri Sean Ellis | World Premiere

In the late 1800s, a man arrives in a remote country village to investigate an attack by a wild animal but discovers a much deeper, sinister force that has both the manor and the townspeople in its grip. Cast: Boyd Holbrook, Kelly Reilly, Alistair Petrie, Roxane Duran, Aine Rose Daly.

How It Ends / US (Dir/Wri Daryl Wein, Zoe Lister-Jones | World Premiere

On the last day on Earth, one woman goes on a journey through L.A. to make it to her last party before the world ends, running into an eclectic cast of characters along the way. Cast: Zoe Lister-Jones, Cailee Spaeny, Olivia Wilde, Fred Armisen, Helen Hunt, Lamorne Morris.

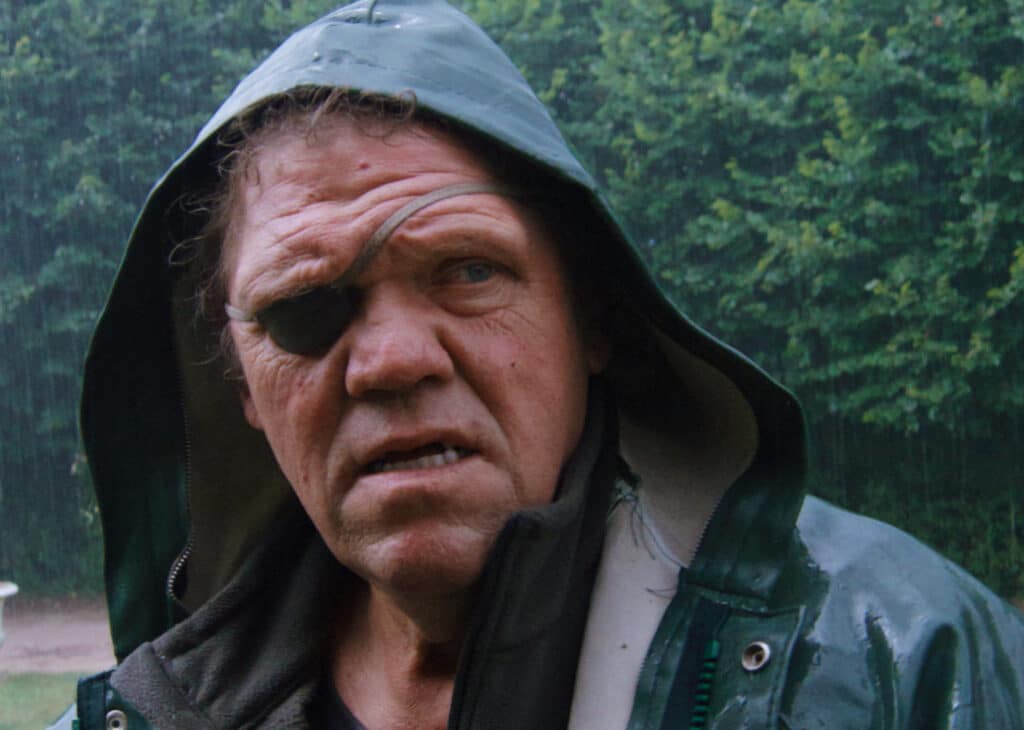

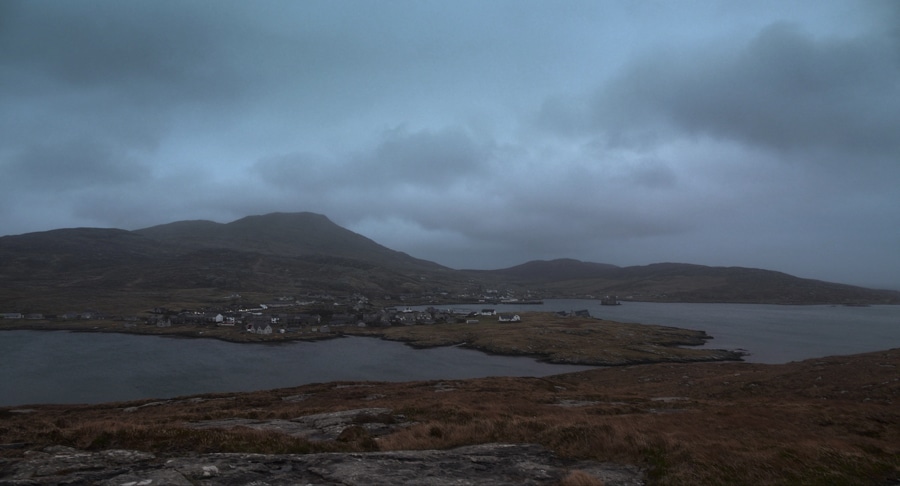

In the Earth / UK (Dir/Wri: Ben Wheatley | World Premiere

As a disastrous virus grips the planet, a scientist and a park scout venture deep into the forest for a routine equipment run. Through the night, their journey becomes a terrifying voyage through the heart of darkness as the forest comes to life around them. Cast: Joel Fry, Ellora Torchia, Hayley Squires, Reece Shearsmith

In the Same Breath / US. (Dir: Nanfu Wang) | World Premiere

How did the Chinese government turn pandemic coverups in Wuhan into a triumph for the Communist party? An essential narrative of firsthand accounts of the novel coronavirus, and a revelatory examination of how propaganda and patriotism shaped the outbreak’s course — both in China and in the U.S. World Premiere, Documentary. DAY ONE

Marvelous and the Black Hole / US (Dir/Wri Kate Tsang, Producer | World Premiere

A teenage delinquent befriends a surly magician who helps her navigate her inner demons and dysfunctional family with sleight of hand magic, in a coming-of-age comedy that touches on unlikely friendships, grief and finding hope in the darkest moments. Cast: Miya Cech, Rhea Perlman, Leonardo Nam, Kannon Omachi, Paulina Lule, Keith Powell.

Mass / US (Dir/Wri: Fran Kranz | World Premiere

Years after a tragic shooting, the parents of both the victim and the perpetrator meet face to face. Cast: Jason Isaacs, Ann Dowd, Martha Plimpton, Reed Birney.

My Name Is Pauli Murray / US (Dirs: Betsy West, Julie Cohen |World premiere

Overlooked by history, Pauli Murray was a legal trailblazer whose ideas influenced RBG’s fight for gender equality and Thurgood Marshall’s landmark civil rights arguments. Featuring never-before-seen footage and audio recordings, a portrait of Murray’s impact as a nonbinary Black luminary: lawyer, activist, poet and priest who transformed our world.

Philly D.A. / US. (Dirs: Ted Passon, Yoni Brook | World Premiere

A groundbreaking inside look at the long-shot election and tumultuous first term of Larry Krasner, Philadelphia’s unapologetic district attorney, and his experiment to upend the criminal justice system from the inside out.

Prisoners of the Ghostland / US. (Dir: Sion Sono, Wri: Aaron Hendry, Reza Sixo Safai | World Premiere

A notorious criminal is sent to rescue an abducted woman who has disappeared into a dark supernatural universe. They must break the evil curse that binds them and escape the mysterious revenants that rule the Ghostland, an East-meets-West vortex of beauty and violence. Cast: Nicolas Cage, Sofia Boutella, Nick Cassavetes, Bill Moseley, Tak Sakaguchi, Yuzuka Nakaya.

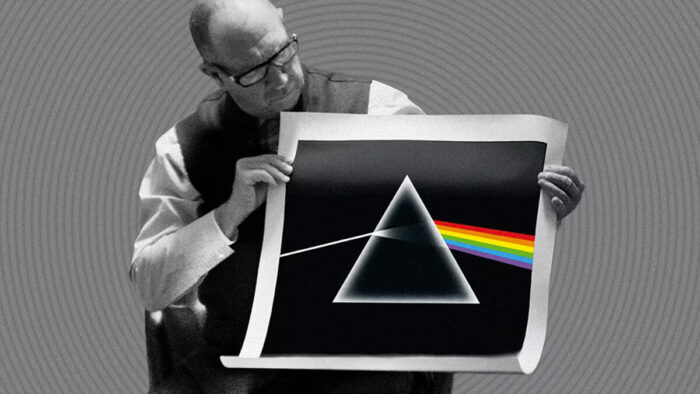

The Sparks Brothers / UK (Dir: Edgar Wright | World Premiere

How can one rock band be successful, underrated, hugely influential and criminally overlooked all at the same time? Take a musical odyssey through five weird and wonderful decades with brothers Russell & Ron Mael, celebrating the inspiring legacy of Sparks: your favorite band’s favourite band.

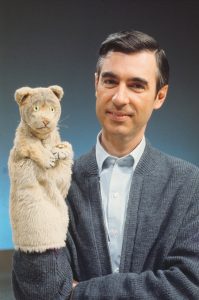

Street Gang: How We Got to Sesame Street / US. (Dir/: Marilyn Agrelo | World Premiere

How did a group of rebels create the world’s most famous street? In 1969 New York, this “gang” of mission-driven artists, writers and educators catalyzed a moment of civil awakening, transforming it into Sesame Street, one of the most influential and impactful television programs in history.

Midnight

Censor / UK (Dir/Wri: Prano Bailey-Bond, Aris: Prano Bailey-Bond, Anthony Fletcher | World Premiere

When film censor Enid discovers an eerie horror that speaks directly to her sister’s mysterious disappearance, she resolves to unravel the puzzle behind the film and its enigmatic director — a quest blurring the lines between fiction and reality in terrifying ways. Cast: Niamh Algar, Nicholas Burns, Vincent Franklin, Sophia La Porta, Adrian Schiller, Michael Smiley.

Coming Home in the Dark / NZ (Dir: James Ashcroft, Wri: Eli Kent, James Ashcroft | World Premiere

A family’s outing descends into terror when teacher Alan Hoaganraad, his wife Jill, and stepsons Maika and Jordon explore an isolated coastline. An unexpected meeting with a pair of drifters, the enigmatic psychopath Mandrake and his accomplice Tubs, thrusts the family into a nightmare when they find themselves captured. Cast: Daniel Gillies, Erik Thomson, Miriama McDowell, Matthias Luafutu.

A Glitch in the Matrix / US (Dir Rodney Ascher | World Premiere

A multimedia exploration of simulation theory — an idea as old as Plato’s Republic and as current as Elon Musk’s Twitter feed — through the eyes of those who suspect our world isn’t real. Part sci-fi mind-scrambler, part horror story, this is a digital journey to the limits of radical doubt.

Knocking / Sweden (Dir: Frida Kempff, Wri: Emma Broström | World Premiere

When Molly moves into her new apartment after a tragic accident, a strange noise from upstairs begins to unnerve her. As its intensity grows, she confronts her neighbors — but no one seems to hear what she is hearing. Cast: Cecilia Milocco.

Mother Schmuckers / Belgium (Dir/Wri: Lenny Guit, Harpo Guit | World Premiere

Issachar & Zabulon, two brothers in their 20s, are supremely stupid and never bored, as madness is part of their daily lives. When they lose their mother’s beloved dog, they have 24 hours to find it — or she will kick them out. Cast: Harpo Guit, Maxi Delmelle, Claire Bodson, Mathieu Amalric, Habib Ben Tanfous.

Special Screenings

Life in a Day 2020 / US/UK. (Dir: Kevin Macdonald | World Premier

An extraordinary, intimate, global portrait of life on our planet, filmed by thousands of people across the world, on a single day: 25th July 2020.

Sundance Film Festival | 28 January – 3 February 2021

Using the finest materials available in those interwar years (marble, bronze and precious wood), the luxurious house consisted of four polished granite facades, surrounded by a large garden with a pergola and swimming pool. A collector and curator, Louis Empain eventually decided that the property was better served as a museum of decorative and contemporary art, and it was donated to the Belgian Nation in 1937. But the Second World War changed everything and the villa languished until 1943, when it was requisitioned by the German army, eventually becoming an embassy for the USSR in peacetime when Empain recovered his property in the beginning of the sixties, before reselling it in 1973. For nearly ten years it was rented to the TV channel RTL then falling to semi-rack and ruin during the 1990s. It was eventually saved by a wealthy family who set up the Boghossian Foundation in 2007, transforming the building into an East West cultural centre and guaranteeing the revival of its fortunes.

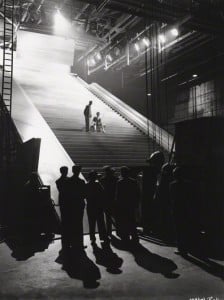

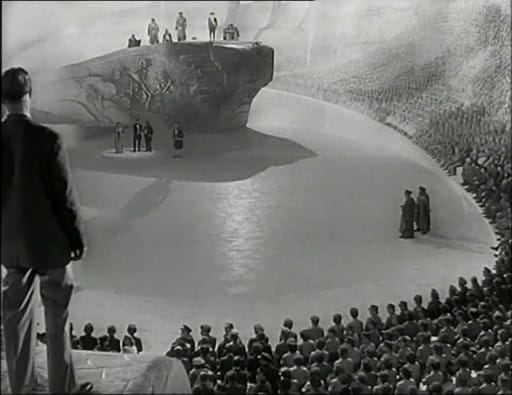

Using the finest materials available in those interwar years (marble, bronze and precious wood), the luxurious house consisted of four polished granite facades, surrounded by a large garden with a pergola and swimming pool. A collector and curator, Louis Empain eventually decided that the property was better served as a museum of decorative and contemporary art, and it was donated to the Belgian Nation in 1937. But the Second World War changed everything and the villa languished until 1943, when it was requisitioned by the German army, eventually becoming an embassy for the USSR in peacetime when Empain recovered his property in the beginning of the sixties, before reselling it in 1973. For nearly ten years it was rented to the TV channel RTL then falling to semi-rack and ruin during the 1990s. It was eventually saved by a wealthy family who set up the Boghossian Foundation in 2007, transforming the building into an East West cultural centre and guaranteeing the revival of its fortunes. Although a brash travesty of H.G.Wells’ original 1898 novel, and despite Steven Spielberg’s 2005 ‘upgrade’ and last autumn’s well-received TV version, George Pal’s original big screen version is still for many the last word in fifties Technicolor destruction on the grand scale (blessed as John Baxter described it with “the smooth unreality of a comic strip”).

Although a brash travesty of H.G.Wells’ original 1898 novel, and despite Steven Spielberg’s 2005 ‘upgrade’ and last autumn’s well-received TV version, George Pal’s original big screen version is still for many the last word in fifties Technicolor destruction on the grand scale (blessed as John Baxter described it with “the smooth unreality of a comic strip”). Filtering the darkest, most dramatic period of modern Jewish history through the instinctive gaze of a dog was an ambitious idea for the best selling Israeli author Asher Kravitz. So Lynn Roth’s efforts to accommodate a young audience in her screen version are laudable but the upshot often cringeworthy.

Filtering the darkest, most dramatic period of modern Jewish history through the instinctive gaze of a dog was an ambitious idea for the best selling Israeli author Asher Kravitz. So Lynn Roth’s efforts to accommodate a young audience in her screen version are laudable but the upshot often cringeworthy.

Dir.: Georgui Balabanov; Documentary with Christo, Jeanne-Claude, Anani Yavashev; Bulgaria 1996, 72 min.

Dir.: Georgui Balabanov; Documentary with Christo, Jeanne-Claude, Anani Yavashev; Bulgaria 1996, 72 min. Dirty weekends don’t come any dirtier than the one in this ferocious indie revenge thriller that has ravishing locations, a twisty storyline, and a female lead who is not just a pretty face.

Dirty weekends don’t come any dirtier than the one in this ferocious indie revenge thriller that has ravishing locations, a twisty storyline, and a female lead who is not just a pretty face. Legendary director Nicholas Ray began his career with this lyrical film noir, the first in a series of existential genre films overflowing with sympathy for America’s outcasts and underdogs. When the wide-eyed fugitive Bowie (Farley Granger), having broken out of prison with some bank robbers, meets the innocent Keechie (Cathy O’Donnell), each recognizes something in the other that no one else ever has.

Legendary director Nicholas Ray began his career with this lyrical film noir, the first in a series of existential genre films overflowing with sympathy for America’s outcasts and underdogs. When the wide-eyed fugitive Bowie (Farley Granger), having broken out of prison with some bank robbers, meets the innocent Keechie (Cathy O’Donnell), each recognizes something in the other that no one else ever has. Concise and pithy, this colourful film is narrated on camera by Samuel Aghoyan, the Superior of the Armenian Church, who takes us through a potted history of his own arrival as a child in the Holy City, and gives a sardonic take on the internecine tiffs that add spice to the daily life of this legendary ecclesiastical HQ sitting proudly in the Christian Quarter of the Old City of Jerusalem.

Concise and pithy, this colourful film is narrated on camera by Samuel Aghoyan, the Superior of the Armenian Church, who takes us through a potted history of his own arrival as a child in the Holy City, and gives a sardonic take on the internecine tiffs that add spice to the daily life of this legendary ecclesiastical HQ sitting proudly in the Christian Quarter of the Old City of Jerusalem. According to traditions, dating back to at least the fourth century, the building houses the two holiest sites in Christianity: the site where Jesus was crucified, at a place known as Calvary or Golgotha, and Jesus’s empty tomb, where he was buried and resurrected. The tomb is enclosed by a 19th-century shrine called the Aedicula. According to the history books, Jerusalem has had a chequered and controversial religious past. But eventually 260 years ago, the English were back in town and set up ‘The Status Quo’, an understanding between religious communities that must be respected across the board.

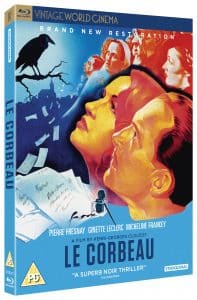

According to traditions, dating back to at least the fourth century, the building houses the two holiest sites in Christianity: the site where Jesus was crucified, at a place known as Calvary or Golgotha, and Jesus’s empty tomb, where he was buried and resurrected. The tomb is enclosed by a 19th-century shrine called the Aedicula. According to the history books, Jerusalem has had a chequered and controversial religious past. But eventually 260 years ago, the English were back in town and set up ‘The Status Quo’, an understanding between religious communities that must be respected across the board. Le Corbeau (1942)

Le Corbeau (1942) Upon its release in 1943, Le Corbeau was condemned by the political left and right and the church, and Clouzot was banned from filmmaking for two years.

Upon its release in 1943, Le Corbeau was condemned by the political left and right and the church, and Clouzot was banned from filmmaking for two years. Woman in Chains (1968)

Woman in Chains (1968)

The former artistic director of the Royal Academy Tim Marlow takes us round Lucian Freud’s first and only exhibition at the London gallery (until 26 January 2020). Although Freud is seen as a modern artist his work is very much connected to that ‘old master’, painterly tradition of Titian and Rembrandt: Few modern artists have explored the human body with such intensity, and such determination. Of course, he was a gambler, a playboy and a bon viveur, but few artists spent as much time in their studio as Lucian Freud. The RA’s Andrea Tarsia explains how he pitted his developing style against his personal life, scrutinising himself as much as his subjects. His single-minded passion focused on self-portraiture as much as on those his was painting:. “Everything is a self-portrait”. Often his subjects are not even named: what mattered more to him was the immediacy of the situation, the spontaneity of the gaze. Accompanied by a jazzy score the doc conveys the energy and charisma that seems to spin off each hypnotic portrait, even a small canvas can dominate a room.

The former artistic director of the Royal Academy Tim Marlow takes us round Lucian Freud’s first and only exhibition at the London gallery (until 26 January 2020). Although Freud is seen as a modern artist his work is very much connected to that ‘old master’, painterly tradition of Titian and Rembrandt: Few modern artists have explored the human body with such intensity, and such determination. Of course, he was a gambler, a playboy and a bon viveur, but few artists spent as much time in their studio as Lucian Freud. The RA’s Andrea Tarsia explains how he pitted his developing style against his personal life, scrutinising himself as much as his subjects. His single-minded passion focused on self-portraiture as much as on those his was painting:. “Everything is a self-portrait”. Often his subjects are not even named: what mattered more to him was the immediacy of the situation, the spontaneity of the gaze. Accompanied by a jazzy score the doc conveys the energy and charisma that seems to spin off each hypnotic portrait, even a small canvas can dominate a room. A sensuality entered the artist’s work in the late 1950s and early 1960 where an emphasis on touch starts to appear. This is most noticeable during a trip to Ian Fleming’s Golden Eye when he painted a Flemish style portrait on a small scrap of copper. It sees him putting his finger on his lips and was the start of this sensuous awareness. The 1960s also marked a switch to hog-hair brushes with ‘Man’s Head’ (1963) and the restless associated portraits, smooth backgrounds allowing the face to stand out. Although Freud admired Francis Bacon’s style of working in a gestural way, his own work increasingly gained a more structural, almost architectural element, as he slotted colours together with pasty brushstrokes, trying to make the paint tell the story.

A sensuality entered the artist’s work in the late 1950s and early 1960 where an emphasis on touch starts to appear. This is most noticeable during a trip to Ian Fleming’s Golden Eye when he painted a Flemish style portrait on a small scrap of copper. It sees him putting his finger on his lips and was the start of this sensuous awareness. The 1960s also marked a switch to hog-hair brushes with ‘Man’s Head’ (1963) and the restless associated portraits, smooth backgrounds allowing the face to stand out. Although Freud admired Francis Bacon’s style of working in a gestural way, his own work increasingly gained a more structural, almost architectural element, as he slotted colours together with pasty brushstrokes, trying to make the paint tell the story. Lucian Freud’s large 1993 self-portrait is defiant – he was 71, but still emanated power and excitement; his greatest fear was losing his mind, but he was also concerned about his physical vigour. ‘Benefits Supervisor Sleeping’ (1995) sold in 2008 for 33.6million dollars – the highest price ever paid for a work by a living artist. Freud carried on painting voraciously until his death on 20 July 2011. He was 88. “Being with him was like being plugged into the National Grid for an hour” said one sitter. “Freud was one of the great European painters of the last 500 years. He’s one of those big figures across the centuries, rather than representative of an era or a movement” says Tim Marlow. “Tradition is a big word but Lucian challenged tradition constantly”. Jasper Sharp adds him to a list that goes back to Holbein; Durer; Cranach and Rembrandt. And he goes on: “Freud gives that list a little shuffle, making us look at Rembrandt a bit differently and Holbein a bit differently through his eyes, and through himself”. And that is a remarkable achievement for any artist. MT

Lucian Freud’s large 1993 self-portrait is defiant – he was 71, but still emanated power and excitement; his greatest fear was losing his mind, but he was also concerned about his physical vigour. ‘Benefits Supervisor Sleeping’ (1995) sold in 2008 for 33.6million dollars – the highest price ever paid for a work by a living artist. Freud carried on painting voraciously until his death on 20 July 2011. He was 88. “Being with him was like being plugged into the National Grid for an hour” said one sitter. “Freud was one of the great European painters of the last 500 years. He’s one of those big figures across the centuries, rather than representative of an era or a movement” says Tim Marlow. “Tradition is a big word but Lucian challenged tradition constantly”. Jasper Sharp adds him to a list that goes back to Holbein; Durer; Cranach and Rembrandt. And he goes on: “Freud gives that list a little shuffle, making us look at Rembrandt a bit differently and Holbein a bit differently through his eyes, and through himself”. And that is a remarkable achievement for any artist. MT

Catherine the Great

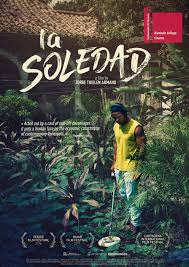

Catherine the Great Dir|Wri: Nicolás Rincón Gille | Doc 136′ | Columbia, Belgium

Dir|Wri: Nicolás Rincón Gille | Doc 136′ | Columbia, Belgium

Dir: Karyn Kusama | Wri: Phil Hay | US Thriller 100′

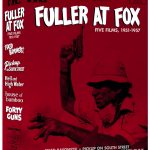

Dir: Karyn Kusama | Wri: Phil Hay | US Thriller 100′ A towering figure of American cinema, Samuel Fuller was a master of the B-movie, a pulp maestro whose iconoclastic vision elevated the American genre film to new heights. After the major success of The Steel Helmet, Fuller was put under contract by Twentieth Century Fox after being impressed by Darryl F. Zanuck’s direct sales pitch (other studios offered Fuller money and tax shelters; Zanuck simply told him, “We make better movies.”).

A towering figure of American cinema, Samuel Fuller was a master of the B-movie, a pulp maestro whose iconoclastic vision elevated the American genre film to new heights. After the major success of The Steel Helmet, Fuller was put under contract by Twentieth Century Fox after being impressed by Darryl F. Zanuck’s direct sales pitch (other studios offered Fuller money and tax shelters; Zanuck simply told him, “We make better movies.”). LA DONA DEL SEGLE | The Woman of the Century

LA DONA DEL SEGLE | The Woman of the Century Dir: Joseph Losey | 97′ UK Crime drama

Dir: Joseph Losey | 97′ UK Crime drama Dominating Pier Paolo Pasolini’s work of the 1970s, is a trio of exuberant dramas that explore three literary classics: Giovanni Boccaccio’s The Decameron (1971), Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales (1972) and The Thousand and One Nights (1974) (often known as The Arabian Nights). These came to be known as his ‘Trilogy of Life’.

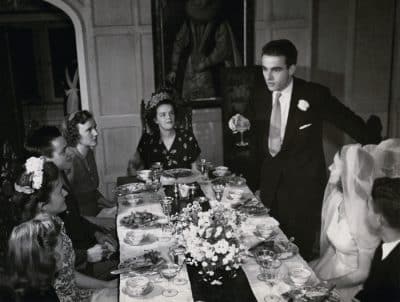

Dominating Pier Paolo Pasolini’s work of the 1970s, is a trio of exuberant dramas that explore three literary classics: Giovanni Boccaccio’s The Decameron (1971), Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales (1972) and The Thousand and One Nights (1974) (often known as The Arabian Nights). These came to be known as his ‘Trilogy of Life’. Joanna Hogg is the only living female filmmaker who portrays a particular English contemporary milieu. Usually creative, invariably white and well-educated, these characters are liberal in outlook and mostly live in London. With such unique sensibilities and vision she is able to understand and convey as certain type of middle class angst (borne out of having to do the right thing, irrespective of personal choice). She did it gracefully in Unrelated (2007), Archipelago (2010) and Exhibition (2013), And she does it peerlessly again here with The Souvenir, a nuanced and delicately drawn story of addiction and strained relationships that very much echoes its time and place: the late 1980s – although it was inspired and takes its name from Fragonard’s painting, a motif that runs through the film.

Joanna Hogg is the only living female filmmaker who portrays a particular English contemporary milieu. Usually creative, invariably white and well-educated, these characters are liberal in outlook and mostly live in London. With such unique sensibilities and vision she is able to understand and convey as certain type of middle class angst (borne out of having to do the right thing, irrespective of personal choice). She did it gracefully in Unrelated (2007), Archipelago (2010) and Exhibition (2013), And she does it peerlessly again here with The Souvenir, a nuanced and delicately drawn story of addiction and strained relationships that very much echoes its time and place: the late 1980s – although it was inspired and takes its name from Fragonard’s painting, a motif that runs through the film.

Elsewhere in the programme, Sasha Collington’s

Elsewhere in the programme, Sasha Collington’s

There are echoes of von Sternbergs’s romantic comedies, particularly Shanghai Gesture, that played out like a roulette wheel. Both directors make use of irony and wit as well as well as farcical moments. The female characters are often victims of male society, they are courtesans or bourgeois women who have failed to fit in with the hypocritical standards of their class. The male characters strut around like peacocks in their dandy-like attire, and soldiers in highly decorative uniforms. Songs and music are key elements in the work of both directors, driving the narrative forward, as here with Strauss, the “Waltz King”.

There are echoes of von Sternbergs’s romantic comedies, particularly Shanghai Gesture, that played out like a roulette wheel. Both directors make use of irony and wit as well as well as farcical moments. The female characters are often victims of male society, they are courtesans or bourgeois women who have failed to fit in with the hypocritical standards of their class. The male characters strut around like peacocks in their dandy-like attire, and soldiers in highly decorative uniforms. Songs and music are key elements in the work of both directors, driving the narrative forward, as here with Strauss, the “Waltz King”. Dir.: Alaa Eddine Aljem; Cast: Younes Bouab, Salah Bensalah, Bouchaits Essamak, Mohmed Naimane, Anas El Vaz, Hassan Ben Bdida, Abdelhaini Kitab, Ahmed Yarziz; Morocco/France/Qatar/Germany, Lebanon; 100 min.

Dir.: Alaa Eddine Aljem; Cast: Younes Bouab, Salah Bensalah, Bouchaits Essamak, Mohmed Naimane, Anas El Vaz, Hassan Ben Bdida, Abdelhaini Kitab, Ahmed Yarziz; Morocco/France/Qatar/Germany, Lebanon; 100 min. Dir: Fritz Lang | Wri: Nunnally Johnson | Cast: Edward G Robinson, Joan Bennett, Raymond Massey | US Film Noir 107′

Dir: Fritz Lang | Wri: Nunnally Johnson | Cast: Edward G Robinson, Joan Bennett, Raymond Massey | US Film Noir 107′ Dir: Richard Lester | Writer: Charles Wood | Cast: John Lennon, Roy Kinnear, Michael Crawford, Michael Hordern, Jack MacGowran | UK Comedy 109′

Dir: Richard Lester | Writer: Charles Wood | Cast: John Lennon, Roy Kinnear, Michael Crawford, Michael Hordern, Jack MacGowran | UK Comedy 109′ What could be more romantic than a train journey? Even if it feels more like a boys own adventure, as many of these British Transport films do. Escaping into the unknown with a promise of excitement and discovery – or just a trip back in time to revisit childhood holidays in the 1960s and 1970s, where the English landscape stretched far and wide from the window of the pullman out of Waterloo, or even Paddington, and not an anorak in sight!

What could be more romantic than a train journey? Even if it feels more like a boys own adventure, as many of these British Transport films do. Escaping into the unknown with a promise of excitement and discovery – or just a trip back in time to revisit childhood holidays in the 1960s and 1970s, where the English landscape stretched far and wide from the window of the pullman out of Waterloo, or even Paddington, and not an anorak in sight!  The four Palme d’Or hopefuls directed by women are— Mati Diop’s Atlantique (she was memorable in

The four Palme d’Or hopefuls directed by women are— Mati Diop’s Atlantique (she was memorable in Jury

Jury Dir: Mike Slee | Carl Knutson, Wendy MacKeigan | Cast: Calum Finlay, Ed Birch, Billy Postlethwaite, Robert Daws, Louis Partridge | Docudrama 46′

Dir: Mike Slee | Carl Knutson, Wendy MacKeigan | Cast: Calum Finlay, Ed Birch, Billy Postlethwaite, Robert Daws, Louis Partridge | Docudrama 46′ Dir: Aleksei German | Wri: Joseph Brodsky | Comedy Drama USSR, 147′

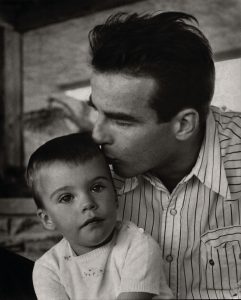

Dir: Aleksei German | Wri: Joseph Brodsky | Comedy Drama USSR, 147′ Co-directing and narrating this eye-opening documentary, Robert Clift (who never knew Monty) digs into a treasure trove of family archives and memorabilia (Brooks recorded everything) to reveal an affectionate, fun-loving talent who loved men and dated and lived with women, according to close friends. Monty chose his roles carefully during the ’40s and ’50s, declining to sign a contract to retain complete artistic independence from the studio system with the ability to pick and chose, and re-write his dialogue. This freedom also enabled him to keep much of his private life out of the headlines, although his memory was eventually sullied by tabloid melodrama with his untimely death at only 45. His acting ability and dazzling looks certainly gained him a place in the Hollywood firmament with a select filmography of just 20 features, four of them Oscar-nominated.

Co-directing and narrating this eye-opening documentary, Robert Clift (who never knew Monty) digs into a treasure trove of family archives and memorabilia (Brooks recorded everything) to reveal an affectionate, fun-loving talent who loved men and dated and lived with women, according to close friends. Monty chose his roles carefully during the ’40s and ’50s, declining to sign a contract to retain complete artistic independence from the studio system with the ability to pick and chose, and re-write his dialogue. This freedom also enabled him to keep much of his private life out of the headlines, although his memory was eventually sullied by tabloid melodrama with his untimely death at only 45. His acting ability and dazzling looks certainly gained him a place in the Hollywood firmament with a select filmography of just 20 features, four of them Oscar-nominated. Particularly interesting are Brooks’ conversations with Patricia Bosworth, one of the film’s talking heads and the author of a 1978 biography of Clift that inspired later biographies, but has so far become the accepted version of events, although she apparently got many details wrong and certainly lost out to Jenny Balaban in the Monty relationship stakes, when Barney Balaban (President of Paramount) invited the young actor to join them on a family holiday. He is seen messing around on the beach where he cuts a dash with his good looks and exuberance.

Particularly interesting are Brooks’ conversations with Patricia Bosworth, one of the film’s talking heads and the author of a 1978 biography of Clift that inspired later biographies, but has so far become the accepted version of events, although she apparently got many details wrong and certainly lost out to Jenny Balaban in the Monty relationship stakes, when Barney Balaban (President of Paramount) invited the young actor to join them on a family holiday. He is seen messing around on the beach where he cuts a dash with his good looks and exuberance. Dir: Alain Resnais; Cast: Sabine Azéma, Pierre Arditi, André Dussollier, Fanny Ardant; France 1986, 112 min.

Dir: Alain Resnais; Cast: Sabine Azéma, Pierre Arditi, André Dussollier, Fanny Ardant; France 1986, 112 min. Turkish cinema is known for its captivating widescreen dramas that reflect the cultural diversity and magnificent scenery of a vibrant nation that stretches from Europe to Asia.

Turkish cinema is known for its captivating widescreen dramas that reflect the cultural diversity and magnificent scenery of a vibrant nation that stretches from Europe to Asia. The Golden Tulip winner 2017 YELLOW HEAT (Sari Sicak) sees an immigrant family desperate to survive in their traditional farm amid encroaching industrialisation. The multi-award winning drama YOZGAT BLUES (2013), set in small town Anatolia, is one to watch for its outstanding performances and smouldering cinematography. Banu Sivaci’s THE PIGEON (main image) won best director at Sofia Film Festival 2018 and is another impressive arthouse tale of a boy finding peace with the animal kingdom, away from the dystopian world in small-town Adana, Southern Turkey. And finally MURTAZA another beautifully crafted and resonant parable about the importance of traditional values in the mountains of Malatya.

The Golden Tulip winner 2017 YELLOW HEAT (Sari Sicak) sees an immigrant family desperate to survive in their traditional farm amid encroaching industrialisation. The multi-award winning drama YOZGAT BLUES (2013), set in small town Anatolia, is one to watch for its outstanding performances and smouldering cinematography. Banu Sivaci’s THE PIGEON (main image) won best director at Sofia Film Festival 2018 and is another impressive arthouse tale of a boy finding peace with the animal kingdom, away from the dystopian world in small-town Adana, Southern Turkey. And finally MURTAZA another beautifully crafted and resonant parable about the importance of traditional values in the mountains of Malatya. Other features and shorts reflect the usual Turkish themes of town versus country, tradition versus the modern world, and the role of women in enlightened society. Another highlight will be Ahmet Boyacioglu’s latest film THE SMELL OF MONEY a tense and startling exposé of financial corruption in contemporary Turkey. And last but not least, a panel of industry professionals will debate the future of the big screen At the Flicks of Netflix? at the Regent Street Cinema on 26th April.

Other features and shorts reflect the usual Turkish themes of town versus country, tradition versus the modern world, and the role of women in enlightened society. Another highlight will be Ahmet Boyacioglu’s latest film THE SMELL OF MONEY a tense and startling exposé of financial corruption in contemporary Turkey. And last but not least, a panel of industry professionals will debate the future of the big screen At the Flicks of Netflix? at the Regent Street Cinema on 26th April. The festival will open at the Barbican on 14 March with Hans Pool’s Bellingcat – Truth in a Post-Truth World, which follows the revolutionary rise of the “citizen investigative journalist” collective known as Bellingcat, dedicated to redefining breaking news by exploring the promise of open source investigation.

The festival will open at the Barbican on 14 March with Hans Pool’s Bellingcat – Truth in a Post-Truth World, which follows the revolutionary rise of the “citizen investigative journalist” collective known as Bellingcat, dedicated to redefining breaking news by exploring the promise of open source investigation.  Dir: Lewis Gilbert | Cast:

Dir: Lewis Gilbert | Cast:  Dir.: Cam Christiansen; Documentary/Animation with David Hare, Elliot Levey, Nayef Rashad; Canada 2017, 82 min.

Dir.: Cam Christiansen; Documentary/Animation with David Hare, Elliot Levey, Nayef Rashad; Canada 2017, 82 min. Diva, grande dame and femme fatale, Stanwyck adapted to any genre, be it comedy, melodrama or thriller. Her natural wit and raw emotion was particularly resonant in her Westerns, where she played resourceful, confident women holding their own in a male-dominated world. The BFI are screening 3 examples in March. Her first western Annie Oakley (George Stevens, 1935) was based on the life of ‘Little Miss Sureshot,’ one of the most famous sharpshooters in American history; Stanwyck oozes confidence in her portrayal of the determined and spirited protagonist. Cecil B. DeMille brought a characteristically epic sense of scale to the western with Union Pacific (1939), about the construction of the First Transcontinental Railroad. Mixed in with the historical elements is a love triangle between a troubleshooter, a gambler, and a train engineer’s daughter played by Stanwyck. The director was mesmerised by her performance, and she became one of his favourite stars. In Forty Guns (Samuel Fuller, 1957), a late-career highlight for Stanwyck, she portrays a wealthy landowner exerting influence over an Arizonian township by commanding a staff of 40 men. Beautifully shot and packed with psychosexual subtext and directed with bravura, Samuel Fuller’s western influenced a generation of filmmakers, including Godard.

Diva, grande dame and femme fatale, Stanwyck adapted to any genre, be it comedy, melodrama or thriller. Her natural wit and raw emotion was particularly resonant in her Westerns, where she played resourceful, confident women holding their own in a male-dominated world. The BFI are screening 3 examples in March. Her first western Annie Oakley (George Stevens, 1935) was based on the life of ‘Little Miss Sureshot,’ one of the most famous sharpshooters in American history; Stanwyck oozes confidence in her portrayal of the determined and spirited protagonist. Cecil B. DeMille brought a characteristically epic sense of scale to the western with Union Pacific (1939), about the construction of the First Transcontinental Railroad. Mixed in with the historical elements is a love triangle between a troubleshooter, a gambler, and a train engineer’s daughter played by Stanwyck. The director was mesmerised by her performance, and she became one of his favourite stars. In Forty Guns (Samuel Fuller, 1957), a late-career highlight for Stanwyck, she portrays a wealthy landowner exerting influence over an Arizonian township by commanding a staff of 40 men. Beautifully shot and packed with psychosexual subtext and directed with bravura, Samuel Fuller’s western influenced a generation of filmmakers, including Godard.

THE GUEST (L’Ospite) ****

THE GUEST (L’Ospite) ****

Dir: Rainer Werner Fassbinder | Sci-fi | Ger, 1973 | 204′

Dir: Rainer Werner Fassbinder | Sci-fi | Ger, 1973 | 204′

Dir/Wri: Denis Côté | Fantasy Drama | Canada, 97′

Dir/Wri: Denis Côté | Fantasy Drama | Canada, 97′ Dir: Joseph H. Lewis; Wri: Muriel Roy Bolton, Music Mischa Bakaleinikoff, Art Director Jerome Pycha Jr | Cast: Nina Foch May Whitty George Macready Roland Varno Anita Bolster Doris Lloyd | Noir thriller US, 64’

Dir: Joseph H. Lewis; Wri: Muriel Roy Bolton, Music Mischa Bakaleinikoff, Art Director Jerome Pycha Jr | Cast: Nina Foch May Whitty George Macready Roland Varno Anita Bolster Doris Lloyd | Noir thriller US, 64’ Dir: William Friedkin | Writer: Mart Crowley | Drama | 118’

Dir: William Friedkin | Writer: Mart Crowley | Drama | 118’ Sam Ellison, 2019, Mexico/Haiti/USA, world premiere

Sam Ellison, 2019, Mexico/Haiti/USA, world premiere Dir.: Anna Odell; Cast: Anna Odell, Mikhael Persbrandt, Shanti Roney, Thure Lindhardt, Trine Dyrholm, Sofie Grabol, Jens Albinus, Vera Vitali, Per Ragnar, Ville Virtanen; Sweden/Denmark 2018, 112 min.

Dir.: Anna Odell; Cast: Anna Odell, Mikhael Persbrandt, Shanti Roney, Thure Lindhardt, Trine Dyrholm, Sofie Grabol, Jens Albinus, Vera Vitali, Per Ragnar, Ville Virtanen; Sweden/Denmark 2018, 112 min. Edgar Henrique Clemente Pêra first studied psychology, but soon realised his vocation in Film at the Portuguese National Conservatory, currently

Edgar Henrique Clemente Pêra first studied psychology, but soon realised his vocation in Film at the Portuguese National Conservatory, currently

This year’s Rotterdam Film Festival takes place from 23 January until the 3rd February with the latest World premieres running alongside 4 sections entitled Bright Future, Voices, Deep Focus and Perspectives – and a cutting-edge arts programme to add a cultural dimension to the 10 days, and this year includes SLEEPCINEMAHOTEL a one off project by Apichatpong Weerasethakul, and never before seen outtakes from Sergei Parajanov’s masterpiece The Colour of Pomegranates (196

This year’s Rotterdam Film Festival takes place from 23 January until the 3rd February with the latest World premieres running alongside 4 sections entitled Bright Future, Voices, Deep Focus and Perspectives – and a cutting-edge arts programme to add a cultural dimension to the 10 days, and this year includes SLEEPCINEMAHOTEL a one off project by Apichatpong Weerasethakul, and never before seen outtakes from Sergei Parajanov’s masterpiece The Colour of Pomegranates (196 T I G E R C O M P E T I T I O N

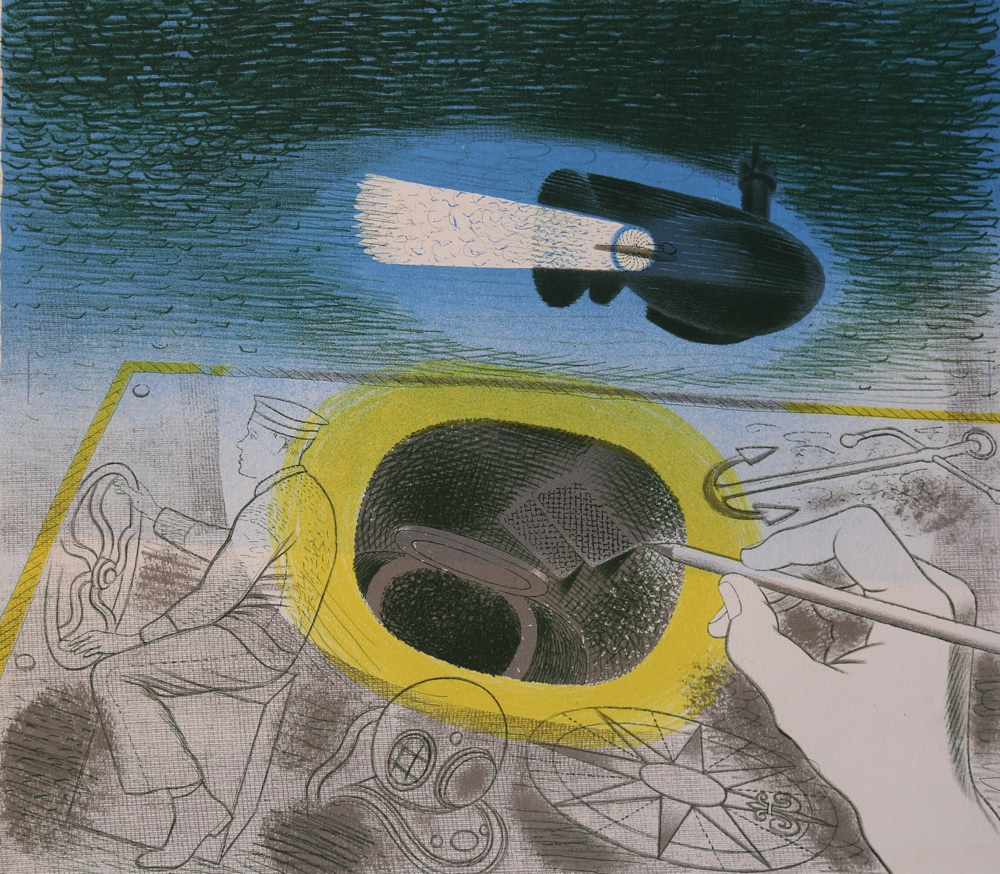

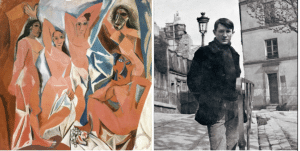

T I G E R C O M P E T I T I O N The Young Picasso

The Young Picasso  But Julien Duvivier’s 1956 thriller DEADLIER THAN THE MALE (Voici les temps des Assassins) somehow manages to outdo them all when it comes to violent women in film Noir: Catherine (Delorme) is the daughter of the drug depending Gabrielle (Bogaert), and tries to escape from the milieu by marrying the restaurant owner Andre Chatelin (Gabin), who has divorced her mother. Telling him that Gabrielle is dead, the scheming Catherine succeeds in marrying the much older man, who soon learns that his wife is lying about her mother. He more or less imprisons her with her mother Antoinette (Bert), also a restaurant owner, who kills her chicken with a whip – which she also uses on Catherine. The frightened woman asks Andre’s friend, the student Gerard (Blain), to kill her husband, but when he refuses, she kills him. Her end – by the fangs of a particular vicious animal – is particularly gruesome. Again, the images of Armand Thirad are undeserving of this blatant ideology.

But Julien Duvivier’s 1956 thriller DEADLIER THAN THE MALE (Voici les temps des Assassins) somehow manages to outdo them all when it comes to violent women in film Noir: Catherine (Delorme) is the daughter of the drug depending Gabrielle (Bogaert), and tries to escape from the milieu by marrying the restaurant owner Andre Chatelin (Gabin), who has divorced her mother. Telling him that Gabrielle is dead, the scheming Catherine succeeds in marrying the much older man, who soon learns that his wife is lying about her mother. He more or less imprisons her with her mother Antoinette (Bert), also a restaurant owner, who kills her chicken with a whip – which she also uses on Catherine. The frightened woman asks Andre’s friend, the student Gerard (Blain), to kill her husband, but when he refuses, she kills him. Her end – by the fangs of a particular vicious animal – is particularly gruesome. Again, the images of Armand Thirad are undeserving of this blatant ideology. The notorious Pépé LE MOKO (Jean Gabin, in a truly iconic performance) plunges into the gangster underworld as a wanted man: women long for him, rivals hope to destroy him, and the law is breathing down his neck at every turn. On the lam in the labyrinthine Casbah of Algiers, Pépé is safe from the clutches of the police–until a Parisian playgirl compels him to risk his life and leave its confines once and for all. One of the most influential films of the 20th century and a landmark of French poetic realism, Julien Duvivier’s Pépé le moko is presented here in its full-length version. AVAILABLE FROM CRITERION COLLECTION | Amazon Prime

The notorious Pépé LE MOKO (Jean Gabin, in a truly iconic performance) plunges into the gangster underworld as a wanted man: women long for him, rivals hope to destroy him, and the law is breathing down his neck at every turn. On the lam in the labyrinthine Casbah of Algiers, Pépé is safe from the clutches of the police–until a Parisian playgirl compels him to risk his life and leave its confines once and for all. One of the most influential films of the 20th century and a landmark of French poetic realism, Julien Duvivier’s Pépé le moko is presented here in its full-length version. AVAILABLE FROM CRITERION COLLECTION | Amazon Prime

Dir: Hajooj Kuka | Cast: Abdallah Ahur, Ganja Chakado, Ekram Marcus, Kamal Ramadan | Drama | 78’

Dir: Hajooj Kuka | Cast: Abdallah Ahur, Ganja Chakado, Ekram Marcus, Kamal Ramadan | Drama | 78’ Dir: Tony Richardson | Writers: Shelagh Delaney, Tony Richardson | Cast: Rita Tushingham, Murray Melvin, Dora Bryan, John Danquah, Robert Stephens | UK | Drama | 101′

Dir: Tony Richardson | Writers: Shelagh Delaney, Tony Richardson | Cast: Rita Tushingham, Murray Melvin, Dora Bryan, John Danquah, Robert Stephens | UK | Drama | 101′

Agnes Varda (b.1928 Belgium)

Agnes Varda (b.1928 Belgium)  Robert De Niro. (b. 1943, US)

Robert De Niro. (b. 1943, US) KHARTOUM is the kind of spectacular, rousing historical adventure that doesn’t get made anymore, certainly not along the same lines as Basil Dearden’s star-studded epic that exposes English colonialism, religious fanaticism, heroism and sacrifice in a magnificent visual masterpiece. Back in the day, it all seemed perfectly harmless to our innocent childhood eyes as we sat round the telly oblivious to the political incorrectness. And that wasn’t the worst thing: it later emerged that over a hundred horses were severely injured or killed immediately during the battle scenes, due to unethical stunt methods of the time.

KHARTOUM is the kind of spectacular, rousing historical adventure that doesn’t get made anymore, certainly not along the same lines as Basil Dearden’s star-studded epic that exposes English colonialism, religious fanaticism, heroism and sacrifice in a magnificent visual masterpiece. Back in the day, it all seemed perfectly harmless to our innocent childhood eyes as we sat round the telly oblivious to the political incorrectness. And that wasn’t the worst thing: it later emerged that over a hundred horses were severely injured or killed immediately during the battle scenes, due to unethical stunt methods of the time. John Schlesinger’s YANKS, a moving and romantic WWII tale of love starring Richard Gere and Vanessa Redgrave is based on Lancashire born Colin Welland’s original story, he also wrote the script.

John Schlesinger’s YANKS, a moving and romantic WWII tale of love starring Richard Gere and Vanessa Redgrave is based on Lancashire born Colin Welland’s original story, he also wrote the script. Dir: Anatoly Vasilyev | Doc | Russia | 167′

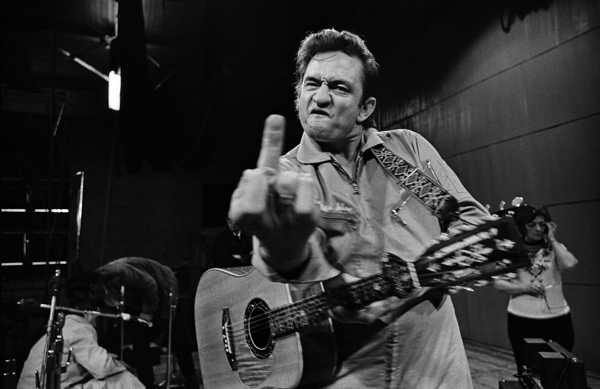

Dir: Anatoly Vasilyev | Doc | Russia | 167′ THE LAST WALTZ is deeply personal yet timeless in its universal appeal. Martin Scorsese’s love song to rock music is a resounding one, and arguably the best concert film of all time. Dated in its Seventies look, but endearingly so, the doc has been remastered onto bluray, and the result is stunning. The film showcases the legendary rock group The Band’s final farewell concert appearance. Joined on stage by more than a dozen special guests, Van Morrison, Eric Clapton, Neil Young and Joni Mitchell perform their iconic numbers to dazzling effect. The Last Waltz started as a concert, but it became a celebration. In between numbers, Scorsese chats to members of The Band, filmed by master DoPs Laszlo Kovacs and Vilmos Zsigmond. Scorsese’s message to the audience, “this film should be played loud” MT

THE LAST WALTZ is deeply personal yet timeless in its universal appeal. Martin Scorsese’s love song to rock music is a resounding one, and arguably the best concert film of all time. Dated in its Seventies look, but endearingly so, the doc has been remastered onto bluray, and the result is stunning. The film showcases the legendary rock group The Band’s final farewell concert appearance. Joined on stage by more than a dozen special guests, Van Morrison, Eric Clapton, Neil Young and Joni Mitchell perform their iconic numbers to dazzling effect. The Last Waltz started as a concert, but it became a celebration. In between numbers, Scorsese chats to members of The Band, filmed by master DoPs Laszlo Kovacs and Vilmos Zsigmond. Scorsese’s message to the audience, “this film should be played loud” MT Russian Film Week is back for the third year running. From 25 November to 2 December the event will take place in London at BFI Southbank, Regent Street Cinema, Curzon Mayfair and Empire Leicester Square before heading to Edinburgh, Cambridge and Oxford.

Russian Film Week is back for the third year running. From 25 November to 2 December the event will take place in London at BFI Southbank, Regent Street Cinema, Curzon Mayfair and Empire Leicester Square before heading to Edinburgh, Cambridge and Oxford. Kristina Söderbaum was Swedish along with several of her compatriots such as Zarah Leander (LA HABANERA) and Ingrid Bergman who appeared in Carl Froelich’s 1938 romantic drama DIE VIER GESELLEN. Then there was the Czech actor Lida Baarova

Kristina Söderbaum was Swedish along with several of her compatriots such as Zarah Leander (LA HABANERA) and Ingrid Bergman who appeared in Carl Froelich’s 1938 romantic drama DIE VIER GESELLEN. Then there was the Czech actor Lida Baarova Later reality and feature films moved even closer: DER GROSSE KÖNIG (Veit Harlan 1942) was premiered in parallel with USSR invasion. Male leader figures like Frederick the Great and Frederick I often featured, such as the hero portraits of Schiller, Schlüter and PARACELSUS (GW Pabst, 1943). During the war years, the newsreels lasted on average forty minutes.

Later reality and feature films moved even closer: DER GROSSE KÖNIG (Veit Harlan 1942) was premiered in parallel with USSR invasion. Male leader figures like Frederick the Great and Frederick I often featured, such as the hero portraits of Schiller, Schlüter and PARACELSUS (GW Pabst, 1943). During the war years, the newsreels lasted on average forty minutes.

Dir: Malene Choi | Writer: Sissel Dalsgaard Thomsen | With Thomas Hwan, Karoline Sofie Lee | Doc | Denmark | 85′

Dir: Malene Choi | Writer: Sissel Dalsgaard Thomsen | With Thomas Hwan, Karoline Sofie Lee | Doc | Denmark | 85′ Writer/Dir: Lars von Trier | Cast: Uma Thurman, Matt Dillon, Riley Keough | Thriller | Bruno Ganz | 155′

Writer/Dir: Lars von Trier | Cast: Uma Thurman, Matt Dillon, Riley Keough | Thriller | Bruno Ganz | 155′ Dir/DoP: David Bickerstaff | 91′ | Art Doc in

Dir/DoP: David Bickerstaff | 91′ | Art Doc in A great collector himself, he was able to buy more painting through sales of his own work, indulging his passion for El Greco, Gauguin and Van Gogh. He idolised the work of Ingrès and his competitor Delacroix. He also developed a passion for photography and often used that to inform his own artwork, and many painters adopt this same technique in portrait painting today.

A great collector himself, he was able to buy more painting through sales of his own work, indulging his passion for El Greco, Gauguin and Van Gogh. He idolised the work of Ingrès and his competitor Delacroix. He also developed a passion for photography and often used that to inform his own artwork, and many painters adopt this same technique in portrait painting today. Dir: Cico Pereira | Spain | Doc | 87′

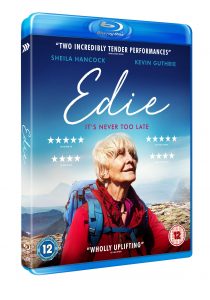

Dir: Cico Pereira | Spain | Doc | 87′ Dir.: Simon Hunter; Cast: Sheila Hancock, Kevin Guthrie, Amy Mason, Wendy Morgan; UK 2017, 102 min.

Dir.: Simon Hunter; Cast: Sheila Hancock, Kevin Guthrie, Amy Mason, Wendy Morgan; UK 2017, 102 min. Director Margaret Salmon, who made the hyper realist fantasy drama Eglantine (2016) develops her worthwhile and enchanting filmic forays into the natural world that started with P.S. in 2002, and continued with Everything That Rises Must Converge (2010); Enemies of the Rose (2011); Gibraltar (2013); Pyramid (2014) and Bird (2016), amongst other titles. Very much festival fare, but valuable in their thoughtful exploration of the British Isles, and often further afield. MT

Director Margaret Salmon, who made the hyper realist fantasy drama Eglantine (2016) develops her worthwhile and enchanting filmic forays into the natural world that started with P.S. in 2002, and continued with Everything That Rises Must Converge (2010); Enemies of the Rose (2011); Gibraltar (2013); Pyramid (2014) and Bird (2016), amongst other titles. Very much festival fare, but valuable in their thoughtful exploration of the British Isles, and often further afield. MT

Dir: Morgan Neville | US | Doc | 94′ | With Bill Clinton, Hilary Clinton, Al Gore, Robert F Kennedy.

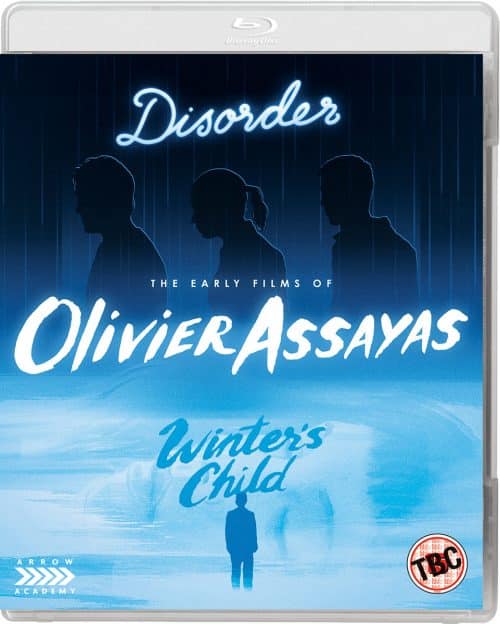

Dir: Morgan Neville | US | Doc | 94′ | With Bill Clinton, Hilary Clinton, Al Gore, Robert F Kennedy.  WINTER’S CHILD (L’ENFANT DE L’HIVER) (1989) ****

WINTER’S CHILD (L’ENFANT DE L’HIVER) (1989) **** Dir: Paul Schrader | Writer: Harold Pinter | Cast: Christopher Walken, Natasha Richardson, Helen Mirren, Rupert Everett | US Thriller | 104′

Dir: Paul Schrader | Writer: Harold Pinter | Cast: Christopher Walken, Natasha Richardson, Helen Mirren, Rupert Everett | US Thriller | 104′ Dir.: Alain Resnais; Cast: Delphine Seyrig, Giorgio Albertazzi, Sacha Pitoeff; France/Italy 1961, 94 min

Dir.: Alain Resnais; Cast: Delphine Seyrig, Giorgio Albertazzi, Sacha Pitoeff; France/Italy 1961, 94 min Dir: Richard Marquand | Cast: Donald Sutherland, Kate Nelligan, Christopher Cazenove, | Action Drama | UK |

Dir: Richard Marquand | Cast: Donald Sutherland, Kate Nelligan, Christopher Cazenove, | Action Drama | UK |

WOMAN AT WAR (2018) – SACD Winner, Cannes Film Festival 2018

WOMAN AT WAR (2018) – SACD Winner, Cannes Film Festival 2018 THE FAVOURITE

THE FAVOURITE

DOGMAN Best Actor, Marcello Forte, Cannes 2018 | Palm Dog Winner 2018

DOGMAN Best Actor, Marcello Forte, Cannes 2018 | Palm Dog Winner 2018  MADELINE’S MADELINE

MADELINE’S MADELINE MUSEUM – Best Script Berlinale 2018

MUSEUM – Best Script Berlinale 2018 IN FABRIC

IN FABRIC THE WILD PEAR TREE – Palme d’Or, Cannes 2018

THE WILD PEAR TREE – Palme d’Or, Cannes 2018  THEY’LL LOVE ME WHEN I’M DEAD (2018)

THEY’LL LOVE ME WHEN I’M DEAD (2018) Dir.: Jean Renoir; Cast: Rene Lefevre, Florelle, Jules Berry, Nadia Sibirskaia; France 1936, 80 min.

Dir.: Jean Renoir; Cast: Rene Lefevre, Florelle, Jules Berry, Nadia Sibirskaia; France 1936, 80 min. Alberto Barbera has announced a stunning line-up of highly anticipated new features and documentaries in celebration of this year’s 71st edition of Venice Film Festival which takes place on the Lido from 28 August until 8 September 2018. 30% of this year’s films are made by women which sounds more positive. Obviously the festival can only programme films offered for screening.

Alberto Barbera has announced a stunning line-up of highly anticipated new features and documentaries in celebration of this year’s 71st edition of Venice Film Festival which takes place on the Lido from 28 August until 8 September 2018. 30% of this year’s films are made by women which sounds more positive. Obviously the festival can only programme films offered for screening. The festival kicks off on the 28th with a remastered 1920 version of THE GOLEM – HOW HE CAME TO BE (ab0ve) complete with musical accompaniment. This year’s festival opening film is Damien Chazelle’s biopic of Neil Armstrong FIRST MAN. There are 21 features and documentaries in the main competition which boasts the latest films from Olivier Assayas (a publishing drama DOUBLE LIVES stars Juliette Binoche), Jacques Audiard (THE SISTERS BROTHERS), Joel and Ethan Coen’s 6-part Western THE BALLAD OF BUSTER SCRUGGS, Brady Corbet’smusical drama VOX LUX; Alfonso Cuaron with ROMA; Luca Guadagnino’s SUSPIRIA sees Tilda Swinton playing 3 parts; Mike Leigh (PETERLOO), Yorgos Lanthimos with an 18th drama entitled THE FAVOURITE; Carlos Reygadas joins from his usual Cannes slot; and Julian Schnabel will present AT ETERNITY’S GATE a drama attempting to get inside the head of Vincent Van Gogh. Not to mention Laszlo Nemes’ Budapest WW1 drama NAPSZÁLLTA, a much awaited second feature and follow up to his Oscar winning Son of Saul.

The festival kicks off on the 28th with a remastered 1920 version of THE GOLEM – HOW HE CAME TO BE (ab0ve) complete with musical accompaniment. This year’s festival opening film is Damien Chazelle’s biopic of Neil Armstrong FIRST MAN. There are 21 features and documentaries in the main competition which boasts the latest films from Olivier Assayas (a publishing drama DOUBLE LIVES stars Juliette Binoche), Jacques Audiard (THE SISTERS BROTHERS), Joel and Ethan Coen’s 6-part Western THE BALLAD OF BUSTER SCRUGGS, Brady Corbet’smusical drama VOX LUX; Alfonso Cuaron with ROMA; Luca Guadagnino’s SUSPIRIA sees Tilda Swinton playing 3 parts; Mike Leigh (PETERLOO), Yorgos Lanthimos with an 18th drama entitled THE FAVOURITE; Carlos Reygadas joins from his usual Cannes slot; and Julian Schnabel will present AT ETERNITY’S GATE a drama attempting to get inside the head of Vincent Van Gogh. Not to mention Laszlo Nemes’ Budapest WW1 drama NAPSZÁLLTA, a much awaited second feature and follow up to his Oscar winning Son of Saul. The out of competition selection is equally exciting and thematically rich. There is Bradley Cooper’s directing debut A STAR IS BORN (left), Charles Manson-themed CHARLIE SAYS from Mary Herron; Amos Gitai’s A TRAMWAY IN JERUSALEM, and Zhang Yimou’s YING (SHADOW). And those whose enjoyed S Craig Zahler’s dynamite Brawl in Cell Block 99 will be pleased to hear that his DRAGGED ACROSS CONCRETE adds Mel Gibson to the previous cast of Jennifer Carpenter and Vince Vaughn. There will be an historic epic set in the time of the French Revolution: UN PEUPLE ET SON ROI features Gaspart Ulliel and Denis Lavant (who also stars in Rick Alverson’s Golden Lion hopeful THE MOUNTAIN) , and Amir Naderi’s MAGIC LANTERN which has the wonderful English talents of Jacqueline Bisset. And talking of England, Mike Leigh’s much gloated over historical epic PETERLOO finally makes it to the competition line-up

The out of competition selection is equally exciting and thematically rich. There is Bradley Cooper’s directing debut A STAR IS BORN (left), Charles Manson-themed CHARLIE SAYS from Mary Herron; Amos Gitai’s A TRAMWAY IN JERUSALEM, and Zhang Yimou’s YING (SHADOW). And those whose enjoyed S Craig Zahler’s dynamite Brawl in Cell Block 99 will be pleased to hear that his DRAGGED ACROSS CONCRETE adds Mel Gibson to the previous cast of Jennifer Carpenter and Vince Vaughn. There will be an historic epic set in the time of the French Revolution: UN PEUPLE ET SON ROI features Gaspart Ulliel and Denis Lavant (who also stars in Rick Alverson’s Golden Lion hopeful THE MOUNTAIN) , and Amir Naderi’s MAGIC LANTERN which has the wonderful English talents of Jacqueline Bisset. And talking of England, Mike Leigh’s much gloated over historical epic PETERLOO finally makes it to the competition line-up Mohsen Makhmalbaf is one of its shining lights of Iranian cinema lauded by critics and cineastes alike on the international film circuit and at home. His Poetic Trilogy is a collection of three of the writer-director’s most lyrical, imaginative works:

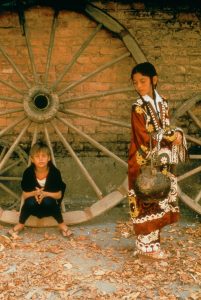

Mohsen Makhmalbaf is one of its shining lights of Iranian cinema lauded by critics and cineastes alike on the international film circuit and at home. His Poetic Trilogy is a collection of three of the writer-director’s most lyrical, imaginative works:  This ‘Poetic Trilogy’ consisting of three features shot between 1996 and 2012, could be called lyrical journeys, very much in the manner of Sergei Paradjanow’s The Colour of Pomegranates. The emphasis is on the visual, and GABBEH starts with an exploration of the colourful titular carpet, floating downstream. The carpet depicts a couple riding a horse, and whilst the owner of the carpet, elderly couple (Hossein and Rogleih Moharami) fight over their past, recounting their romantic miss-adventures, the girl in the picture, also called Gabbeh (Djodat), springs to live, to tell her story. Living with Nomads, Gabbeh is looking forward to marry her beloved for a long time. But her repressive father always invents new reasons to postpone the marriage: her uncle (Ghalandari) is used as a reason for the father to stall. First Gabbeh has to wait for the uncle’s return from a trip, than he has to find a wife for himself – somebody who will sing near a river “like a canary”. But Gabbeh tires of seeing her future husband only as a shadow on the horizon, and she will have to make a decision.

This ‘Poetic Trilogy’ consisting of three features shot between 1996 and 2012, could be called lyrical journeys, very much in the manner of Sergei Paradjanow’s The Colour of Pomegranates. The emphasis is on the visual, and GABBEH starts with an exploration of the colourful titular carpet, floating downstream. The carpet depicts a couple riding a horse, and whilst the owner of the carpet, elderly couple (Hossein and Rogleih Moharami) fight over their past, recounting their romantic miss-adventures, the girl in the picture, also called Gabbeh (Djodat), springs to live, to tell her story. Living with Nomads, Gabbeh is looking forward to marry her beloved for a long time. But her repressive father always invents new reasons to postpone the marriage: her uncle (Ghalandari) is used as a reason for the father to stall. First Gabbeh has to wait for the uncle’s return from a trip, than he has to find a wife for himself – somebody who will sing near a river “like a canary”. But Gabbeh tires of seeing her future husband only as a shadow on the horizon, and she will have to make a decision. Filmed in a small town in Tajikistan, SILENCE tells the story of ten-year old Khorshid (Normatova), who is blind, but earns a living as a tuner of musical instruments, to support his mother. His master always threatens him with dismissal, since the young boy gets obsessed with the four opening notes of Beethoven’s Fifth, which keeps him distracted. A young woman (Abdelahyeva) acts as his eyes, selling bread and fruit near the river. She wears cherries instead of earrings and flower petals instead of nail varnish. In one scene, she becomes very nervous, when a soldier looks like he wants to arrest a woman, who is not adequately covered. SILENCE is a symphony of images (DoP Ebrahim Ghafori) and sounds, a magic and sensual journey into the world of a special childhood.

Filmed in a small town in Tajikistan, SILENCE tells the story of ten-year old Khorshid (Normatova), who is blind, but earns a living as a tuner of musical instruments, to support his mother. His master always threatens him with dismissal, since the young boy gets obsessed with the four opening notes of Beethoven’s Fifth, which keeps him distracted. A young woman (Abdelahyeva) acts as his eyes, selling bread and fruit near the river. She wears cherries instead of earrings and flower petals instead of nail varnish. In one scene, she becomes very nervous, when a soldier looks like he wants to arrest a woman, who is not adequately covered. SILENCE is a symphony of images (DoP Ebrahim Ghafori) and sounds, a magic and sensual journey into the world of a special childhood.

EL AMOR MENOS PENSADO

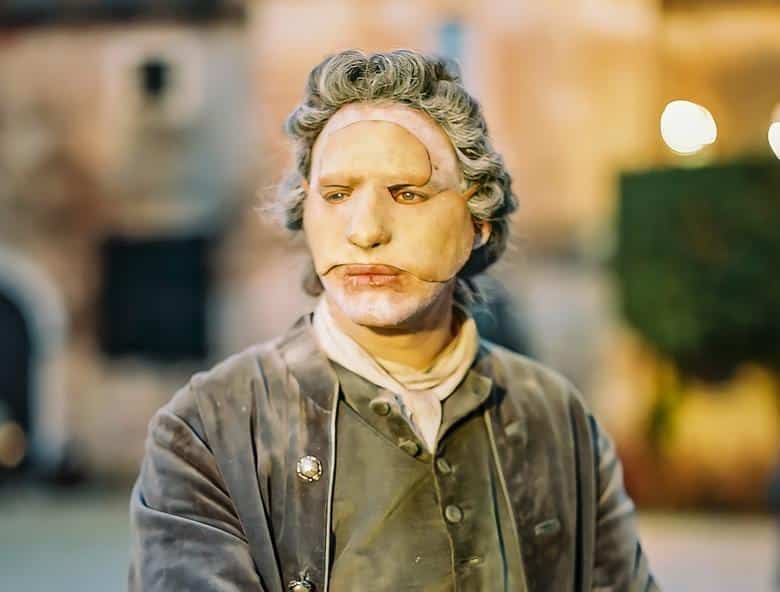

EL AMOR MENOS PENSADO ANGELO

ANGELO DER UNSCHULDIGE / THE INNOCENT

DER UNSCHULDIGE / THE INNOCENT EL REINO

EL REINO ENTRE DOS AGUAS | ISAKI LACUESTA | SPAIN

ENTRE DOS AGUAS | ISAKI LACUESTA | SPAIN  HIGH LIFE.

HIGH LIFE. ILLANG: THE WOLF BRIGADE

ILLANG: THE WOLF BRIGADE LE CAHIER NOIR / THE BLACK BOOK

LE CAHIER NOIR / THE BLACK BOOK QUIÉN TE CANTARÁ

QUIÉN TE CANTARÁ ROJO

ROJO VISION

VISION YULI

YULI Dir: Billy Wilder | Writers: Billy Wilder, Harry Kurnitz, Lawrence B Marcus | Cast: Marlene Dietrich, Tyrone Power, Charles Laughton, Elsa Lanchester, John Williams, Torin Thatcher, Norma Varden, Una O’Connor | US Crime Drama | 116′

Dir: Billy Wilder | Writers: Billy Wilder, Harry Kurnitz, Lawrence B Marcus | Cast: Marlene Dietrich, Tyrone Power, Charles Laughton, Elsa Lanchester, John Williams, Torin Thatcher, Norma Varden, Una O’Connor | US Crime Drama | 116′ In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans traditional jazz musicians gather together to play and talk about the soul of their city which celebrates its 300th Anniversary in 2018.

In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans traditional jazz musicians gather together to play and talk about the soul of their city which celebrates its 300th Anniversary in 2018.  Dir: Mark Cousins | Doc | UK |

Dir: Mark Cousins | Doc | UK |

Dir: Rebecca Miller | Documentary with Deborah Feldman, Vithika Yadav, Rokudenashiko, Leyla Hussein, Doris Wagner; Germany/Switzerland/UK/USA/Japan 2018, 95 min.

Dir: Rebecca Miller | Documentary with Deborah Feldman, Vithika Yadav, Rokudenashiko, Leyla Hussein, Doris Wagner; Germany/Switzerland/UK/USA/Japan 2018, 95 min. Dir: Michael Cimino | US War Thriller | 183′

Dir: Michael Cimino | US War Thriller | 183′ Dir: Peter Medak | Cast: George C Scott, Trish Van Devere, Joh Colicos, Melvyn Douglas | Horror | 107′

Dir: Peter Medak | Cast: George C Scott, Trish Van Devere, Joh Colicos, Melvyn Douglas | Horror | 107′

THE MICHAEL POWELL AWARD FOR BEST BRITISH FEATURE FILM

THE MICHAEL POWELL AWARD FOR BEST BRITISH FEATURE FILM THE AWARD FOR BEST PERFORMANCE IN A BRITISH FEATURE FILM

THE AWARD FOR BEST PERFORMANCE IN A BRITISH FEATURE FILM THE AWARD FOR BEST INTERNATIONAL FEATURE FILM

THE AWARD FOR BEST INTERNATIONAL FEATURE FILM THE AWARD FOR BEST DOCUMENTARY FEATURE FILM

THE AWARD FOR BEST DOCUMENTARY FEATURE FILM

Dir: Yuen Woo-ping | Action drama | China | 90′

Dir: Yuen Woo-ping | Action drama | China | 90′

Dir: Paul Van Carter | Doc | UK |

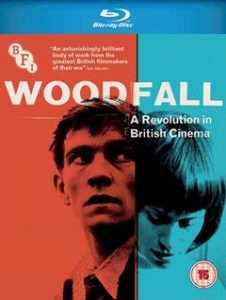

Dir: Paul Van Carter | Doc | UK | Woodfall Film Productions was founded in 1958 by English director Tony Richardson (1928-1991), the American producer Harry Saltzman (later of James Bond fame) and the English author and playwright John Osborne, whose play Look back in Anger was filmed by Richardson in 1959 as the opus number of the company that championed the British New Wave. So it’s only fitting that Richardson should finish the circle in 1984 with Hotel New Hampshire, creating a sub-genre of dram-com, which was later developed by Wes Anderson.

Woodfall Film Productions was founded in 1958 by English director Tony Richardson (1928-1991), the American producer Harry Saltzman (later of James Bond fame) and the English author and playwright John Osborne, whose play Look back in Anger was filmed by Richardson in 1959 as the opus number of the company that championed the British New Wave. So it’s only fitting that Richardson should finish the circle in 1984 with Hotel New Hampshire, creating a sub-genre of dram-com, which was later developed by Wes Anderson. The Entertainer featured Laurence Olivier in the title role, reprising his stage role from the Royal Court, co-written by John Osborne from his own play. There is nothing heroic about Olivier’s Archie Rice: he is a bankrupt womaniser, exploiting his long suffering wife Phoebe (de Banzie) and using Tina Lapford (Field) – who came second in the Miss Britain contest – and her wealthy family to prolong his stage career. Not even the death of his son in the Suez conflict can deter him from his vain pursuit of a long dead career. Using his father – who dies on stage – for his own advantage, Archie sinks deeper and deeper. There is a poignant scene with his film daughter Jean (Plowright), whom he asks: “What would think, if I married a woman your age?” and Jean answers exasperated “Oh. Daddy”. At the end of productions, Olivier would marry Plowright, after his divorce from Vivien Leigh. Shot partly at Margate, this is a bleak portrait of show business, shot in brilliant black and white by the great Oswald Morris (Moby Dick, A Farewell to Arms).