Marrakech Film Festival is back after two years under a new artistic director Remi Bonhomie. With its fabulous climate, medieval walled Medina dating back to the Berber empire, exotic palaces and lush gardens – Yves Saint Laurent’s famous Majorelle is the standout – Marrakech is the ideal location for a winter festival celebrating international cinema with an emphasis on Moroccan and MENA film in general. The 19th edition includes an international competition, gala screenings, the Moroccan Panorama, and the 11th continent celebrating innovative film that challenge cinematic boundaries and

Here is the festival line-up:

INTERNATIONAL COMPETITION

ALMA VIVA

by Cristèle Alves Meira / Portugal

Principal Cast: Lua Michel, Ana Padrão, Jacqueline Corado, Duarte Pina, Catherine Salée

ASHKAL

by Youssef Chebbi / Tunisia

Principal Cast: Fatma Oussaifi, Mohamed Houcine Grayaa, Rami Harrabi, Hichem Riahi, Nabil Trabelsi, Bahri Rahali

ASTRAKAN

by David Depesseville / France

Principal Cast: Mirko Giannini Samuel, Jehnny Beth, Bastien Bouillon

AUTOBIOGRAPHY

by Makbul Mubarak / Indonesia

Principal Cast: Kevin Ardilova, Arswendy Bening Swara, Haru Sandra, Rukman Rosadi, Yusuf Mahardika

THE BLUE CAFTAN (Le Bleu du Caftan/Azraq al-qaftan)

by Maryam Touzani / Morocco

Principal Cast: Lubna Azabal, Saleh Bakri, Ayoub Missioui

FARAWAY SONG (Cañçao ao Longe)

by Clarissa Campolina / Brazil

Principal Cast: Mônica Maria, Carlos Francisco, Jhon Narvaez, Margô Assis, Matilde Biagi, Ricardo Campos

PETROL

by Alena Lodkina / Australia

Principal Cast: Nathalie Morris, Hannah Lynch

RED SHOES (Zapatos rojos)

by Carlos Eichelmann Kaiser / Mexico Principal Cast: Eustacio Ascacio, Natalia Solian, Phanie Molina, Irine Herrera

RICEBOY SLEEPS

by Anthony Shim / Canada

Principal Cast: Choi Seung-yoon, Ethan Hwang, Dohyun Noel Hwang, Anthony Shim, Hunter Dillon

SAVAGE (Amina)

by Ahmed Abdullahi / Sweden

Principal Cast: Nimco Ahmed Ali, Jamilah Mohamed Kirih, Ariane Castellanos

SNOW AND THE BEAR (Kar ve Ayı)

by Selcen Ergun / Turkey

Principal Cast: Merve Dizdar, Saygın Soysal, Asiye Dinçsoy, Erkan Bektaş, Derya Pınar Ak

A TALE OF SHEMROON (Chevalier noir)

by Emad Aleebrahim Dehkordi / Iran

Principal Cast: Iman Sayad Borhani, Payar Allahyari, Masoumeh Beygi, Behzad Dorani

THE TASTE OF APPLES IS RED (Ta’am al-tufah, ahmar)

by Ehab Tarabieh / Syria

Principal Cast: Mariam J. Khoury, Tarik Kopty, Rula Blal, Hussien Rumiah, Maisa Abd Elhadi, Suheil Haddad

THUNDER (Foudre)

by Carmen Jaquier / Switzerland

Principal Cast: Lilith Grasmug, Mermoz Melchior, Benjamin Python, Noah Watzlawick, Sabine Timoteo

GALA SCREENINGS

Opening Film

GUILLERMO DEL TORO’S PINOCCHIO

by Guillermo del Toro / Mexico et Mark Gustafson / USA

Principal Cast: Ewan McGregor, David Bradley, Gregory Mann, Finn Wolfhard, Cate Blanchett, John Turturro, Ron Perlman, Tim Blake Nelson, Burn Gorman, Christoph Waltz, Tilda Swinton

ARMAGEDDON TIME

by James Gray / USA

Principal Cast: Anne Hathaway, Jeremy Strong, Banks Repeta, Anthony Hopkins

BOY FROM HEAVEN (Walad min al-janna)

by Tarik Saleh / Sweden

Principal Cast: Tawfeek Barhom, Fares Fares, Mohammad Bakri, Makram J. Khoury, Mehdi Dehbi

MARLOWE

by Neil Jordan / Ireland

Principal Cast: Liam Neeson, Diane Kruger, Jessica Lange, Alan Cumming, Danny Huston

MASTER GARDENER

by Paul Schrader / USA

Principal Cast: Joel Edgerton, Sigourney Weaver, Quintessa Swindell

MEDITERRANEAN FEVER

by Maha Haj / Palestine

Principal Cast: Amer Hlehel, Ashraf Farah, Anat Hadid, Samir Elias, Cynthia Saleem, Shaden Kanboura

THE SITTING DUCK (La Syndicaliste)

by Jean-Paul Salomé / France

Principal Cast: Isabelle Huppert, Grégory Gadebois, François-Xavier Demaison, Pierre Deladonchamps, Alexandra Maria Lara, Gilles Cohen with the participation of de Marina Foïs, Yvan Attal

THE SWIMMERS

by Sally El Hosaini / Egypt/United Kingdom

Principal Cast: Mana Issa, Nathalie Issa, Matthias Schweighöfer, Ahmed Malek, James Krishna Floyd, Ali Suleiman

SPECIAL SCREENINGS

BURNING DAYS (Kurak Günler)

by Emin Alper / Turkey

Principal Cast: Selahattin Paşali, Ekin Koç, Erol Babaoğlu, Erdem Şenocak, Selin Yeninci

CORSAGE

by Marie Kreutzer / Austria

Principal Cast: Vicky Krieps, Florian Teichtmeister, Aaron Friesz, Katharina Lorenz, Jeanne Werner, Alma Hasun

THE DAMNED DON’T CRY

by Fyzal Boulifa / Morocco

Principal Cast: Abdellah El Hajjouji, Aïcha Tebbae, Antoine Reinartz

DECLARATION (Ariyippu)

by Mahesh Narayanan / India

Principal Cast: Kunchacko Boban, Divya Prabha, Lovleen Misra, Danish Husain, Kannan Arunasalam

THE ETERNAL DAUGHTER

by Joanna Hogg / United Kingdom

Principal Cast: Tilda Swinton, August Joshi,

Carly-Sophie Davies, Joseph Mydell, Crispin Buxton

GODLAND

(Vanskabte Land | Volga∂a Land)

by Hlynur Pálmason / Iceland

Principal Cast: Elliott Crosset Hove, Ingvar Sigur∂sson, Vic Carmen Sonne, Jacob Hauberg Lohmann, Ída Mekkín Hlynsdóttir

LES HARKIS

by Philippe Faucon / France

Principal Cast: Théo Cholbi, Mohamed Mouffok, Pierre Lottin, Yannick Choirat, Omar Boulakirba

MONICA

by Andrea Pallaoro / Italy

Principal Cast: Trace Lysette, Patricia Clarkson, Emily Browning, Joshua Close, Adriana Barraza

NAYOLA

by José Miguel Ribeiro / Portugal

Voices: Elisângela Rita, Vitória Soares, Feliciana Délcia Guia, Marinela Furtado, José Adelino Barcelo Carvalho

NO BEARS (Khers nist)

by Jafar Panahi / Iran

Principal Cast: Jafar Panahi, Naser Hashemi, Vahid Mobaseri, Bakhtiar Panjei, Mina Kavani

QUEENS (Reines)

by Yasmine Benkiran / Morocco

Principal Cast: Nisrin Erradi, Nisrine Benchara, Rayhan Guaran, Jalila Talemsi, Mohamed Nider Hamid

RETURN TO SEOUL (Retour à Seoul)

by Davy Chou / Cambodia

Principal Cast: Park Ji-min, Oh Kwang-rok, Guka Han, Kim Sun-young, Yoann Zimmer, Louis-Do Lencquesaing

RHINEGOLD (Rheingold)

by Fatih Akin / Germany

Principal Cast: Emilio Sakraya, Kardo Razzazi, Mona Pirzad, Arman Kashani, Hüseyin Top, Sogol Faghani

SAINT OMER (Saint-Omer)

by Alice Diop / France

Principal Cast: Kayije Kagame, Guslagie Malanda, Valérie Dréville, Aurélia Petit, Robert Cantarella

UNDER THE FIG TREES (Sous les figues)

by Erige Sehiri / Tunisia

Principal Cast: Fide Fdhili, Feten Fdhili, Ameni Fdhili, Samar Sifi, Leila Ouhebi

THE 11TH CONTINENT

BEIRUT AL-LIKA (Beirut, the Encounter)

by Borhane Alaouié / Lebanon

Principal Cast: Haitham El Amine, Nadine Acoury, Renée Deek, Refaat Haidar, Hussam Sabbah, Najwa Haidar, Rafic Najem (1981)

DRY GROUND BURNING (Mato seco em chamas)

by Joana Pimenta / Portugal

and Adirley Queiros / Brazil

Principal Cast: Joana Darc Furtado, Léa Alves Da Silva, Andreia Vieira, Débora Alencar, Gleide Firmino, Mara Alves

EAMI

by Paz Encina / Paraguay

Principal Cast: Anel Picanerai, Curia Chiquejno Etacoro, Ducubaide Chiquenoi, Basui Picanerai Etacore, Lucas Etacori

FATHER’S DAY

by Kivu Ruhorahoza / Rwanda

Principal Cast: Mediatrice Kayitesi, Aline Amike, Yves Kijyana, Cedric Gisubizo

FRAGMENTS FROM HEAVEN

by Adnane Baraka / Morocco

Documentary

With: Mohamed Oubakha, Abderrahman Ibhi, Lahcen Oubakha, Youssef Oubakha

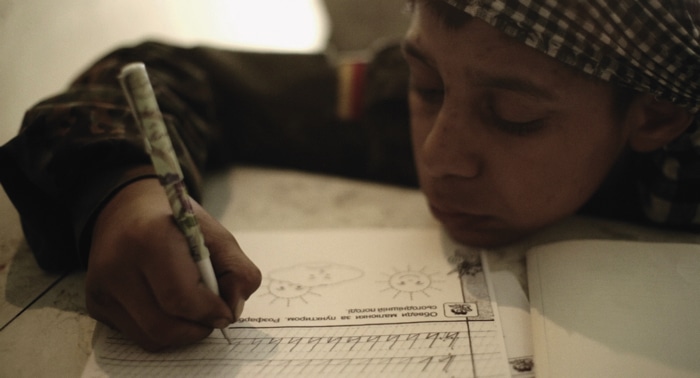

IN FIELDS OF WORDS: CONVERSATIONS WITH SAMAR YAZBEK (As-sahel al-mumtani)

by Rania Stephan / Lebanon

Documentary

With: Samar Yazbek

MARINER OF THE MOUNTAINS (Marinheiro das Montanhas)

by Karim Aïnouz / Brazil

MUNA MOTO (The Child of Another)

by Jean-Pierre Dikongué-Pipa / Cameroon Principal Cast: David Endéné, Arlette Din Bell, Philippe Abia, Gisèle Dikongué-Pipa, Jeanne Mvondo (1975)

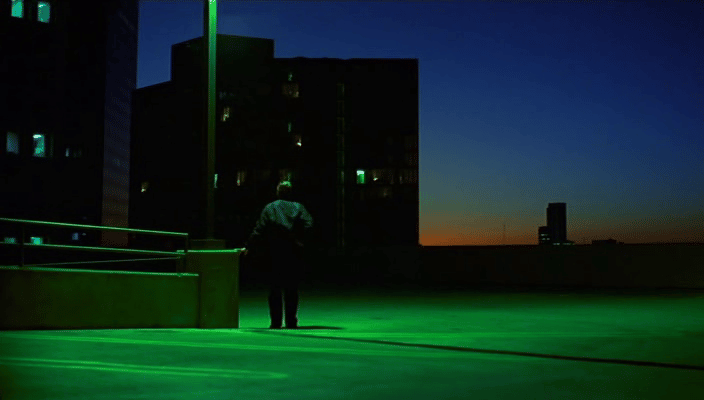

PACIFICTION

by Albert Serra / Spain

Principal Cast: Benoît Magimel, Pahoa Mahagafanau, Marc Susini, Matahi Pambrun, Alexandre Melo

POLARIS

by Ainara Vera / France

Documentary

REEL NO. 21 AKA RESTORING SOLIDARITY

by Mohanad Yaqubi / Palestine, Morocco

Documentary

REWIND & PLAY

by Alain Gomis / Senegal

Documentary

MARRAKECH FILM FESTIVAL | 11 -20 NOVEMBER 2022

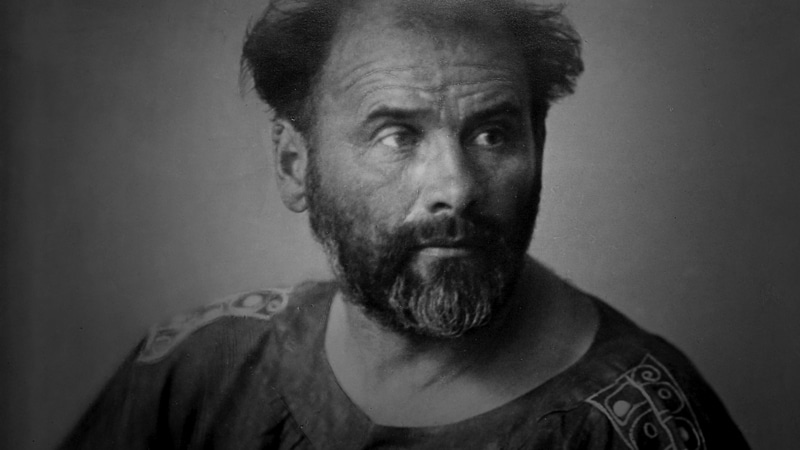

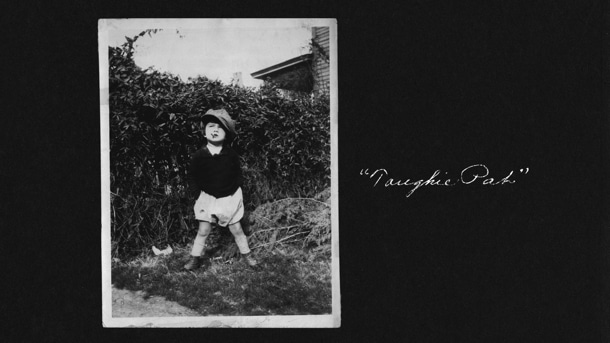

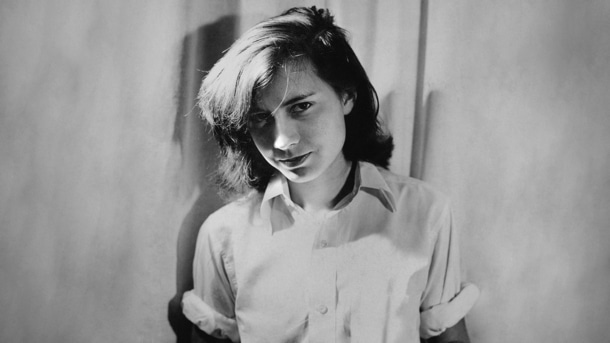

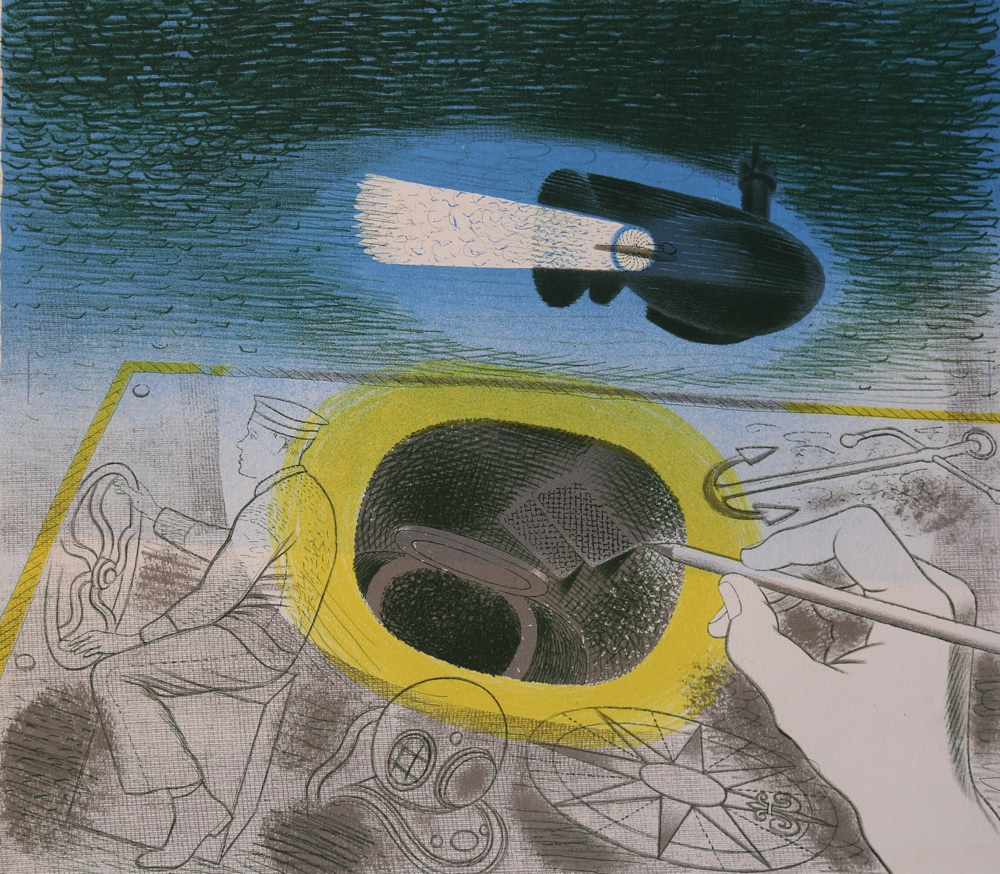

EUROPA (1931) Photo credit: Themerson Estate

EUROPA (1931) Photo credit: Themerson Estate