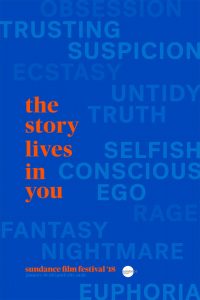

In Park City Utah, the SUNDANCE INSTITUTE founder ROBERT REDFORD and his programmer John Cooper set the indie film agenda for 2018 with a slew of provocative new titles for this year’s festival which ran from 18-28 January.

In Park City Utah, the SUNDANCE INSTITUTE founder ROBERT REDFORD and his programmer John Cooper set the indie film agenda for 2018 with a slew of provocative new titles for this year’s festival which ran from 18-28 January.

Among the newcomers were Paul Dano (with Wildlife) and Rupert Everett (with The Happy Prince) presenting their directorial debuts and new films from Desiree Akhavan: The Miseducation of Cameron Post and Gus van Sant: Don’t Worry, He Won’t Get Far On Foot starring Joaquin Phoenix and Rooney Mara.

WINNERS – THESE ARE THE FILMS WHICH WILL BE CROPPING UP OVER THE NEXT YEAR IN LOCAL ARTHOUSE CINEMAS

The Kindergarten Teacher | DIRECTING AWARD | US DRAMATIC

The Kindergarten Teacher | DIRECTING AWARD | US DRAMATIC

U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Sara Colangelo, Producers: Celine Rattray, Trudie Styler, Maggie Gyllenhaal, Osnat Handelsman-Keren, Talia Kleinhendler) — Lisa Spinelli is a Staten Island teacher who is unusually devoted to her students. When she discovers one of her five-year-olds is a prodigy, she becomes fascinated with the boy, ultimately risking her family and freedom to nurture his talent. Based on the acclaimed Israeli film. Cast: Maggie Gyllenhaal, Parker Sevak, Rosa Salazar, Anna Barynishikov, Michael Chernus, Gael Garcia Bernal. World Premiere

The Guilty / Denmark | AUDIENCE AWARD | WORLD CINEMA DRAMATIC

The Guilty / Denmark | AUDIENCE AWARD | WORLD CINEMA DRAMATIC

(Director: Gustav Möller, Screenwriters: Gustav Möller, Emil Nygaard Albertsen, Producer: Lina Flint) Alarm dispatcher Asger Holm answers an emergency call from a kidnapped woman; after a sudden disconnection, the search for the woman and her kidnapper begins. With the phone as his only tool, Asger enters a race against time to solve a crime that is far bigger than he first thought. Cast: Jakob Cedergren, Jessica Dinnage, Johan Olsen, Omar Shargawi. World Premiere

Of Fathers and Sons / Germany, Syria, Lebanon | WORLD CINEMA GRAND JURY PRIZE | DOCUMENTARY

(Director: Talal Derki, Producers: Ansgar Frerich, Eva Kemme, Tobias N. Siebert, Hans Robert Eisenhauer) — Talal Derki returns to his homeland where he gains the trust of a radical Islamist family, sharing their daily life for over two years. His camera focuses on Osama and his younger brother Ayman, providing an extremely rare insight into what it means to grow up in an Islamic Caliphate. North American Premiere

On Her Shoulders / U.S.A | US DIRECTING AWARD – DOCUMENTARY

On Her Shoulders / U.S.A | US DIRECTING AWARD – DOCUMENTARY

(Director: Alexandria Bombach, Producers: Marie Therese Guirgis, Hayley Pappas, Brock Williams, Bryn Mooser, Adam Bardach) — A Yazidi genocide and ISIS sexual slavery survivor, 23-year-old Nadia Murad is determined to tell the world her story. As her journey leads down paths of advocacy and fame, she becomes the voice of her people and their best hope to spur the world to action. International Premiere

The Miseducation of Cameron Post / U.S.A. | US GRAND JURY AWARD

(Director: Desiree Akhavan, Screenwriters: Desiree Akhavan, Cecilia Frugiuele, Producers: Cecilia Frugiuele, Jonathan Montepare, Michael B. Clark, Alex Turtletaub) — 1993: after being caught having sex with the prom queen, a girl is forced into a gay conversion therapy center. Based on Emily Danforth’s acclaimed and controversial coming-of-age novel. Cast: Chloë Grace Moretz, Sasha Lane, Forrest Goodluck, John Gallagher Jr., Jennifer Ehle. World Premiere

Butterflies / WORLD CINEMA GRAND JURY PRIZE | DOCUMENTARY

Butterflies / WORLD CINEMA GRAND JURY PRIZE | DOCUMENTARY

Turkey (Director and screenwriter: Tolga Karaçelik, Producers: Tolga Karaçelik, Diloy Gülün, Metin Anter) — In the Turkish village of Hasanlar, three siblings who neither know each other nor anything about their late father, wait to bury his body. As they start to find out more about their father and about each other, they also start to know more about themselves. Cast: Tolga Tekin, Bartu Küçükçağlayan, Tuğçe Altuğ, Serkan Keskin, Hakan Karsak. World Premiere

THIS IS HOME | AUDIENCE AWARD: US Dramatic / U.S.A., Jordan (Director: Alexandra Shiva, Producer: Lindsey Megrue) This is an intimate portrait of four Syrian families arriving in Baltimore, Maryland and struggling to find their footing. With eight months to become self-sufficient, they must forge ahead to rebuild their lives. When the travel ban adds further complications, their strength and resilience are put to the test. World Premiere

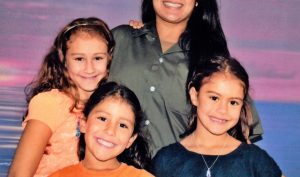

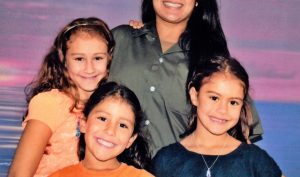

The Sentence / U.S.A | AUDIENCE AWARD | US Documentary

The Sentence / U.S.A | AUDIENCE AWARD | US Documentary

(Director: Rudy Valdez, Producers: Sam Bisbee, Jackie Kelman Bisbee) — Cindy Shank, mother of three, is serving a 15-year sentence in federal prison for her tangential involvement with a Michigan drug ring years earlier. This intimate portrait of mandatory minimum drug sentencing’s devastating consequences, captured by Cindy’s brother, follows her and her family over the course of ten years. World Premiere

BURDEN/AUDIENCE AWARD 2018 | US Dramatic

BURDEN/AUDIENCE AWARD 2018 | US Dramatic

U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Andrew Heckler, Producers: Robbie Brenner, Jincheng, Bill Kenwright) — After opening a KKK shop, Klansman Michael Burden falls in love with a single mom who forces him to confront his senseless hatred. After leaving the Klan and with nowhere to turn, Burden is taken in by an African-American reverend, and learns tolerance through their combined love and faith. Cast: Garrett Hedlund, Forest Whitaker, Andrea Riseborough, Tom Wilkinson, Usher Raymond. World Premiere

NANCY / U.S.A.| WALDO SALT SCREENWRITING AWARD

NANCY / U.S.A.| WALDO SALT SCREENWRITING AWARD

(Director and screenwriter: Christina Choe, Producers: Amy Lo, Michelle Cameron, Andrea Riseborough) — Blurring lines between fact and fiction, Nancy becomes increasingly convinced she was kidnapped as a child. When she meets a couple whose daughter went missing thirty years ago, reasonable doubts give way to willful belief – and the power of emotion threatens to overcome all rationality. Cast: Andrea Riseborough, J. Smith-Cameron, Steve Buscemi, Ann Dowd, John Leguizamo. World Premiere

KAILASH | US GRAND JURY PRIZE / U.S.A | DOCUMENTARY

(Director: Derek Doneen, Producers: Davis Guggenheim, Sarah Anthony) — As a young man, Kailash Satyarthi promised himself that he would end child slavery in his lifetime. In the decades since, he has rescued more than eighty thousand children and built a global movement. This intimate and suspenseful film follows one man’s journey to do what many believed was impossible. World Premiere.

SEARCH / U.S.A. | THE AUDIENCE AWARD | NEXT

(Director: Aneesh Chaganty, Screenwriters: Aneesh Chaganty, Sev Ohanian, Producers: Timur Bekmambetov, Sev Ohanian, Adam Sidman, Natalie Qasabian) — After his 16-year-old daughter goes missing, a desperate father breaks into her laptop to look for clues to find her. A thriller that unfolds entirely on computer screens. Cast: John Cho, Debra Messing. World Premiere. WINNER: 2018 Alfred P. Sloan Feature Film Prize.

Crime + Punishment / U.S.A. | SPECIAL AWARD FOR SOCIAL IMPACT

Crime + Punishment / U.S.A. | SPECIAL AWARD FOR SOCIAL IMPACT

(Director: Stephen Maing) — Over four years of unprecedented access, the story of a brave group of black and Latino whistleblower cops and one unrelenting private investigator who, amidst a landmark lawsuit, risk everything to expose illegal quota practices and their impact on young minorities. World Premiere

Shirkers / U.S.A. | DIRECTING AWARD | World Cinema Documentary

(Director and screenwriter: Sandi Tan, Producers: Sandi Tan, Jessica Levin, Maya Rudolph) — In 1992, teenager Sandi Tan shot Singapore’s first indie road movie with her enigmatic American mentor Georges – who then vanished with all the footage. Twenty years later, the 16mm film is recovered, sending Tan, now a novelist in Los Angeles, on a personal odyssey in search of Georges’ vanishing footprints. World Premiere

And Breathe Normally / Iceland, Sweden, Belgium | DIRECTING AWARD | World cinema Dramatic

(Director and screenwriter: Ísold Uggadóttir, Producers: Skúli Malmquist, Diana Elbaum, Annika Hellström, Lilja Ósk Snorradóttir, Inga Lind Karlsdóttir) — At the edge of Iceland’s Reykjanes peninsula, two women’s lives will intersect – for a brief moment – while trapped in circumstances unforeseen. Between a struggling Icelandic mother and an asylum seeker from Guinea-Bissau, a delicate bond will form as both strategize to get their lives back on track. Cast: Kristín Thóra Haraldsdóttir, Babetida Sadjo, Patrik Nökkvi Pétursson. World Premiere

U.S. DRAMATIC COMPETITION

Presenting the world premieres of 16 narrative feature films, the Dramatic Competition offers Festivalgoers a first look at groundbreaking new voices in American independent film. Films that have premiered in this category in recent years include Fruitvale Station, Patti Cake$, Swiss Army Man and The Diary of a Teenage Girl.

American Animals / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Bart Layton, Producers: Derrin Schlesinger, Katherine Butler, Dimitri Doganis, Mary Jane Skalski) — The unbelievable but mostly true story of four young men who mistake their lives for a movie and attempt one of the most audacious art heists in U.S. history. Cast: Evan Peters, Barry Keoghan, Blake Jenner, Jared Abrahamson, Ann Dowd, Udo Kier. World Premiere

BLAZE / U.S.A. (Director: Ethan Hawke, Screenwriters: Ethan Hawke, Sybil Rosen, Producers: Jake Seal, John Sloss, Ryan Hawke, Ethan Hawke) — A reimagining of the life and times of Blaze Foley, the unsung songwriting legend of the Texas Outlaw Music movement; he gave up paradise for the sake of a song. Cast: Benjamin Dickey, Alia Shawkat, Josh Hamilton, Charlie Sexton. World Premiere

Blindspotting / U.S.A. (Director: Carlos Lopez Estrada, Screenwriters: Rafael Casal, Daveed Diggs, Producers: Keith Calder, Jess Calder, Rafael Casal, Daveed Diggs) — A buddy comedy in a world that won’t let it be one. Cast: Daveed Diggs, Rafael Casal, Janina Gavankar, Jasmine Cephas Jones. World Premiere.

Blindspotting / U.S.A. (Director: Carlos Lopez Estrada, Screenwriters: Rafael Casal, Daveed Diggs, Producers: Keith Calder, Jess Calder, Rafael Casal, Daveed Diggs) — A buddy comedy in a world that won’t let it be one. Cast: Daveed Diggs, Rafael Casal, Janina Gavankar, Jasmine Cephas Jones. World Premiere.

Eighth Grade / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Bo Burnham, Producers: Scott Rudin, Eli Bush, Christopher Storer, Lila Yacoub) — Thirteen-year-old Kayla endures the tidal wave of contemporary suburban adolescence as she makes her way through the last week of middle school — the end of her thus far disastrous eighth grade year — before she begins high school. Cast: Elsie Fisher, Josh Hamilton. World Premiere.

I Think We’re Alone Now / U.S.A. (Director: Reed Morano, Screenwriter: Mike Makowsky, Producers: Fred Berger, Brian Kavanaugh-Jones, Fernando Loureiro, Roberto Vasconcellos, Peter Dinklage, Mike Makowsky) — The apocalypse proves a blessing in disguise for one lucky recluse – until a second survivor arrives with the threat of companionship. Cast: Peter Dinklage, Elle Fanning. World Premiere

I Think We’re Alone Now / U.S.A. (Director: Reed Morano, Screenwriter: Mike Makowsky, Producers: Fred Berger, Brian Kavanaugh-Jones, Fernando Loureiro, Roberto Vasconcellos, Peter Dinklage, Mike Makowsky) — The apocalypse proves a blessing in disguise for one lucky recluse – until a second survivor arrives with the threat of companionship. Cast: Peter Dinklage, Elle Fanning. World Premiere

Lizzie / U.S.A. (Director: Craig William Macneill, Screenwriter: Bryce Kass, Producers: Naomi Despres, Liz Destro) — Based on the 1892 murder of Lizzie Borden’s family in Fall River, MA, this tense psychological thriller lays bare the legend of Lizzie Borden to reveal the much more complex, poignant and truly terrifying woman within — and her intimate bond with the family’s young Irish housemaid, Bridget Sullivan. Cast: Chloë Sevigny, Kristen Stewart, Jamey Sheridan, Fiona Shaw, Kim Dickens, Denis O’Hare. World Premiere

Monster / U.S.A. (Director: Anthony Mandler, Screenwriters: Radha Blank, Cole Wiley, Janece Shaffer, Producers: Tonya Lewis Lee, Nikki Silver, Aaron L. Gilbert, Mike Jackson, Edward Tyler Nahem) — “Monster” is what the prosecutor calls 17 year old honors student and aspiring filmmaker Steve Harmon. Charged with felony murder for a crime he says he did not commit, the film follows his dramatic journey through a complex legal battle that could leave him spending the rest of his life in prison. Cast: Kelvin Harrison Jr., Jeffrey Wright, Jennifer Hudson, Rakim Mayers, Jennifer Ehle, Tim Blake Nelson. World Premiere

Monsters and Men / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Reinaldo Marcus Green, Producers: Elizabeth Lodge Stepp, Josh Penn, Eddie Vaisman, Julia Lebedev, Luca Borghese) — This interwoven narrative explores the aftermath of a police killing of a black man. The film is told through the eyes of the bystander who filmed the act, an African-American police officer and a high-school baseball phenom inspired to take a stand. Cast: John David Washington, Anthony Ramos, Kelvin Harrison Jr., Chanté Adams, Nicole Beharie, Rob Morgan. World Premiere

Sorry to Bother You / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Boots Riley, Producers: Nina Yang Bongiovi, Forest Whitaker, Charles King, George Rush, Jonathan Duffy, Kelly Williams) — In a speculative and dystopian not-too-distant future, black telemarketer Cassius Green discovers a magical key to professional success – which propels him into a macabre universe. Cast: Lakeith Stanfield, Tessa Thompson, Steven Yeun, Jermaine Fowler, Armie Hammer, Omari Hardwicke. World Premiere

The Tale / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Jennifer Fox, Producers: Oren Moverman, Lawrence Inglee, Laura Rister, Mynette Louie, Sol Bondy, Simone Pero) — An investigation into one woman’s memory as she’s forced to re-examine her first sexual relationship and the stories we tell ourselves in order to survive; based on the filmmaker’s own story. Cast: Laura Dern, Isabel Nelisse, Jason Ritter, Elizabeth Debicki, Ellen Burstyn, Common. World Premiere

The Tale / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Jennifer Fox, Producers: Oren Moverman, Lawrence Inglee, Laura Rister, Mynette Louie, Sol Bondy, Simone Pero) — An investigation into one woman’s memory as she’s forced to re-examine her first sexual relationship and the stories we tell ourselves in order to survive; based on the filmmaker’s own story. Cast: Laura Dern, Isabel Nelisse, Jason Ritter, Elizabeth Debicki, Ellen Burstyn, Common. World Premiere

TYREL / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Sebastian Silva, Producers: Jacob Wasserman, Max Born) — Tyler spirals out of control when he realizes he’s the only black person attending a weekend birthday party in a secluded cabin. Cast: Jason Mitchell, Christopher Abbott, Michael Cera, Caleb Landry Jones, Ann Dowd. World Premiere

Wildlife / U.S.A. (Director: Paul Dano, Screenwriters: Paul Dano, Zoe Kazan, Producers: Andrew Duncan, Alex Saks, Oren Moverman, Ann Ruark, Jake Gyllenhaal, Riva Marker) — Montana, 1960: A portrait of a family in crisis. Based on the novel by Richard Ford. Cast: Carey Mulligan, Ed Oxenbould, Bill Camp, Jake Gyllenhaal. World Premiere

Wildlife / U.S.A. (Director: Paul Dano, Screenwriters: Paul Dano, Zoe Kazan, Producers: Andrew Duncan, Alex Saks, Oren Moverman, Ann Ruark, Jake Gyllenhaal, Riva Marker) — Montana, 1960: A portrait of a family in crisis. Based on the novel by Richard Ford. Cast: Carey Mulligan, Ed Oxenbould, Bill Camp, Jake Gyllenhaal. World Premiere

U.S. DOCUMENTARY COMPETITION

Sixteen world-premiere American documentaries that illuminate the ideas, people and events that shape the present day. Films that have premiered in this category in recent years include Chasing Coral, Life, Animated, Cartel Land and City of Gold.

Bisbee ’17 / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Robert Greene, Producers: Douglas Tirola, Susan Bedusa, Bennett Elliott) — An old mining town on the Arizona-Mexico border finally reckons with its darkest day: the deportation of 1200 immigrant miners exactly 100 years ago. Locals collaborate to stage recreations of their controversial past. Cast: Fernando Serrano, Laurie McKenna, Ray Family, Mike Anderson, Graeme Family, Richard Hodges. World Premier

Dark Money / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Kimberly Reed, Producer: Katy Chevigny) — “Dark money” contributions, made possible by the U.S. Supreme Court’s Citizens United ruling, flood modern American elections – but Montana is showing Washington D.C. how to solve the problem of unlimited anonymous money in politics. World Premiere

The Devil We Know / U.S.A. (Director: Stephanie Soechtig, Producers: Kristin Lazure, Stephanie Soechtig, Joshua Kunau, Carly Palmour) — Unraveling one of the biggest environmental scandals of our time, a group of citizens in West Virginia take on a powerful corporation after they discover it has knowingly been dumping a toxic chemical — now found in the blood of 99.7% of Americans — into the local drinking water supply. World Premiere.

The Devil We Know / U.S.A. (Director: Stephanie Soechtig, Producers: Kristin Lazure, Stephanie Soechtig, Joshua Kunau, Carly Palmour) — Unraveling one of the biggest environmental scandals of our time, a group of citizens in West Virginia take on a powerful corporation after they discover it has knowingly been dumping a toxic chemical — now found in the blood of 99.7% of Americans — into the local drinking water supply. World Premiere.

Hal / U.S.A. (Director: Amy Scott, Producers: Christine Beebe, Jonathan Lynch, Brian Morrow) — Hal Ashby’s obsessive genius led to an unprecedented string of Oscar®-winning classics, including Harold and Maude, Shampoo and Being There. But as contemporaries Coppola, Scorsese and Spielberg rose to blockbuster stardom in the 1980s, Ashby’s uncompromising nature played out as a cautionary tale of art versus commerce. World Premiere

Hal / U.S.A. (Director: Amy Scott, Producers: Christine Beebe, Jonathan Lynch, Brian Morrow) — Hal Ashby’s obsessive genius led to an unprecedented string of Oscar®-winning classics, including Harold and Maude, Shampoo and Being There. But as contemporaries Coppola, Scorsese and Spielberg rose to blockbuster stardom in the 1980s, Ashby’s uncompromising nature played out as a cautionary tale of art versus commerce. World Premiere

Hale County This Morning, This Evening / U.S.A. (Director: RaMell Ross, Screenwriter: Maya Krinsky, Producers: Joslyn Barnes, RaMell Ross, Su Kim) — An exploration of coming-of-age in the Black Belt of the American South, using stereotypical imagery to fill in the landscape between iconic representations of black men and encouraging a new way of looking, while resistance to narrative suspends conclusive imagining – allowing the viewer to complete the film. World Premiere

Inventing Tomorrow / U.S.A. (Director: Laura Nix, Producers: Diane Becker, Melanie Miller, Laura Nix) — Take a journey with young minds from around the globe as they prepare their projects for the largest convening of high school scientists in the world, the Intel International Science and Engineering Fair (ISEF). Watch these passionate innovators find the courage to face the planet’s environmental threats while navigating adolescence. World Premiere. THE NEW CLIMATE

Kusama – Infinity / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Heather Lenz, Producers: Karen Johnson, Heather Lenz, Dan Braun, David Koh) — Now one of the world’s most celebrated artists, Yayoi Kusama broke free of the rigid society in which she was raised, and overcame sexism, racism, and mental illness to bring her artistic vision to the world stage. At 88 she lives in a mental hospital and continues to create art. World Premiere

The Last Race / U.S.A. (Director: Michael Dweck, Producers: Michael Dweck, Gregory Kershaw) — A cinematic portrait of a small town stock car track and the tribe of drivers that call it home as they struggle to hold onto an American racing tradition. The avant-garde narrative explores the community and its conflicts through an intimate story that reveals the beauty, mystery and emotion of grassroots auto racing. World Premiere

Minding the Gap / U.S.A. (Director: Bing Liu, Producer: Diane Quon) — Three young men bond together to escape volatile families in their Rust Belt hometown. As they face adult responsibilities, unexpected revelations threaten their decade-long friendship. World Premiere

The Price of Everything / U.S.A. (Director: Nathaniel Kahn, Producers: Jennifer Blei Stockman, Debi Wisch, Carla Solomon) — With unprecedented access to pivotal artists and the white-hot market surrounding them, this film dives deep into the contemporary art world, holding a funhouse mirror up to our values and our times – where everything can be bought and sold.World Premiere

Seeing Allred / U.S.A. (Directors: Sophie Sartain, Roberta Grossman, Producers: Roberta Grossman, Sophie Sartain, Marta Kauffman, Robbie Rowe Tollin, Hannah KS Canter) — Gloria Allred overcame trauma and personal setbacks to become one of the nation’s most famous women’s rights attorneys. Now the feminist firebrand takes on two of the biggest adversaries of her career, Bill Cosby and Donald Trump, as sexual violence allegations grip the nation and keep her in the spotlight. World Premiere

Seeing Allred / U.S.A. (Directors: Sophie Sartain, Roberta Grossman, Producers: Roberta Grossman, Sophie Sartain, Marta Kauffman, Robbie Rowe Tollin, Hannah KS Canter) — Gloria Allred overcame trauma and personal setbacks to become one of the nation’s most famous women’s rights attorneys. Now the feminist firebrand takes on two of the biggest adversaries of her career, Bill Cosby and Donald Trump, as sexual violence allegations grip the nation and keep her in the spotlight. World Premiere

Three Identical Strangers / U.S.A. (Director: Tim Wardle, Producer: Becky Read) — New York,1980: three complete strangers accidentally discover that they’re identical triplets, separated at birth. The 19-year-olds’ joyous reunion catapults them to international fame, but also unlocks an extraordinary and disturbing secret that goes beyond their own lives – and could transform our understanding of human nature forever. World Premiere

Three Identical Strangers / U.S.A. (Director: Tim Wardle, Producer: Becky Read) — New York,1980: three complete strangers accidentally discover that they’re identical triplets, separated at birth. The 19-year-olds’ joyous reunion catapults them to international fame, but also unlocks an extraordinary and disturbing secret that goes beyond their own lives – and could transform our understanding of human nature forever. World Premiere

WORLD CINEMA DRAMATIC COMPETITION

Twelve films from emerging filmmaking talents around the world offer fresh perspectives and inventive styles. Films that have premiered in this category in recent years include The Nile Hilton Incident, Second Mother, Berlin Syndrome and The Lure.

Dead Pigs / China (Director and screenwriter: Cathy Yan, Producers: Clarissa Zhang, Jane Zheng, Zhangke Jia, Mick Aniceto, Amy Aniceto) — A bumbling pig farmer, a feisty salon owner, a sensitive busboy, an expat architect and a disenchanted rich girl converge and collide as thousands of dead pigs float down the river towards a rapidly-modernizing Shanghai, China. Based on true events. Cast: Vivian Wu, Haoyu Yang, Mason Lee, Meng Li, David Rysdahl. World Premiere

Dead Pigs / China (Director and screenwriter: Cathy Yan, Producers: Clarissa Zhang, Jane Zheng, Zhangke Jia, Mick Aniceto, Amy Aniceto) — A bumbling pig farmer, a feisty salon owner, a sensitive busboy, an expat architect and a disenchanted rich girl converge and collide as thousands of dead pigs float down the river towards a rapidly-modernizing Shanghai, China. Based on true events. Cast: Vivian Wu, Haoyu Yang, Mason Lee, Meng Li, David Rysdahl. World Premiere

Holiday / Denmark, Netherlands, Sweden (Director: Isabella Eklöf, Screenwriters: Isabella Eklöf, Johanne Algren, Producer: David B. Sørensen) — A love triangle featuring the trophy girlfriend of a petty drug lord, caught up in a web of luxury and violence in a modern dark gangster tale set in the beautiful port city of Bodrum on the Turkish Riviera. Cast: Victoria Carmen Sonne, Lai Yde, Thijs Römer. World Premiere

Holiday / Denmark, Netherlands, Sweden (Director: Isabella Eklöf, Screenwriters: Isabella Eklöf, Johanne Algren, Producer: David B. Sørensen) — A love triangle featuring the trophy girlfriend of a petty drug lord, caught up in a web of luxury and violence in a modern dark gangster tale set in the beautiful port city of Bodrum on the Turkish Riviera. Cast: Victoria Carmen Sonne, Lai Yde, Thijs Römer. World Premiere

Loveling / Brazil, Uruguay (Director: Gustavo Pizzi, Screenwriters: Gustavo Pizzi, Karine Teles, Producers: Tatiana Leite, Rodrigo Letier, Agustina Chiarino, Fernando Epstein) — On the outskirts of Rio de Janeiro, Irene has only a few days to overcome her anxiety and renew her strength before sending her eldest son out into the world. Cast: Karine Teles, Otavio Muller, Adriana Esteves, Konstantinos Sarris, Cesar Troncoso. World Premiere.

Loveling / Brazil, Uruguay (Director: Gustavo Pizzi, Screenwriters: Gustavo Pizzi, Karine Teles, Producers: Tatiana Leite, Rodrigo Letier, Agustina Chiarino, Fernando Epstein) — On the outskirts of Rio de Janeiro, Irene has only a few days to overcome her anxiety and renew her strength before sending her eldest son out into the world. Cast: Karine Teles, Otavio Muller, Adriana Esteves, Konstantinos Sarris, Cesar Troncoso. World Premiere.

Pity / Greece, Poland (Director: Babis Makridis, Screenwriters: Efthimis Filippou, Babis Makridis, Producers: Amanda Livanou, Christos V. Konstantakopoulos, Klaudia Śmieja, Beata Rzeźniczek) — The story of a man who feels happy only when he is unhappy: addicted to sadness, with such need for pity, that he’s willing to do everything to evoke it from others. This is the life of a man in a world not cruel enough for him. Cast: Yannis Drakopoulos, Evi Saoulidou, Nota Tserniafski, Makis Papadimitriou, Georgina Chryskioti, Evdoxia Androulidaki. World Premiere

Pity / Greece, Poland (Director: Babis Makridis, Screenwriters: Efthimis Filippou, Babis Makridis, Producers: Amanda Livanou, Christos V. Konstantakopoulos, Klaudia Śmieja, Beata Rzeźniczek) — The story of a man who feels happy only when he is unhappy: addicted to sadness, with such need for pity, that he’s willing to do everything to evoke it from others. This is the life of a man in a world not cruel enough for him. Cast: Yannis Drakopoulos, Evi Saoulidou, Nota Tserniafski, Makis Papadimitriou, Georgina Chryskioti, Evdoxia Androulidaki. World Premiere

The Queen of Fear / Argentina, Denmark (Directors: Valeria Bertuccelli, Fabiana Tiscornia, Screenwriter: Valeria Bertuccelli, Producers: Benjamin Domenech, Santiago Gallelli, Matias Roveda, Juan Vera, Juan Pablo Galli, Christian Faillace) — Only one month left until the premiere of The Golden Time, the long-awaited solo show by acclaimed actress Robertina. Far from focused on the preparations for this new production, Robertina lives in a state of continuous anxiety that turns her privileged life into an absurd and tumultuous landscape. Cast: Valeria Bertuccelli, Diego Velázquez, Gabriel Eduardo “Puma” Goity, Darío Grandinetti. World Premiere

Rust / Brazil (Director: Aly Muritiba, Screenwriters: Aly Muritiba, Jessica Candal, Producer: Antônio Junior) — Tati and Renet were already trading pics, videos and music by their cellphones and on the last school trip they started making eye contact. However, what could be the beginning of a love story becomes an end. Cast: Giovanni De Lorenzi, Tifanny Dopke, Enrique Diaz, Clarissa Kiste, Duda Azevedo, Pedro Inoue. World Premiere

Rust / Brazil (Director: Aly Muritiba, Screenwriters: Aly Muritiba, Jessica Candal, Producer: Antônio Junior) — Tati and Renet were already trading pics, videos and music by their cellphones and on the last school trip they started making eye contact. However, what could be the beginning of a love story becomes an end. Cast: Giovanni De Lorenzi, Tifanny Dopke, Enrique Diaz, Clarissa Kiste, Duda Azevedo, Pedro Inoue. World Premiere

Time Share (Tiempo Compartido) / Mexico, Netherlands (Director: Sebastián Hofmann, Screenwriters: Julio Chavezmontes, Sebastián Hofmann, Producer: Julio Chavezmontes) — Two haunted family men join forces in a destructive crusade to rescue their families from a tropical paradise, after becoming convinced that an American timeshare conglomerate has a sinister plan to take their loved ones away. Cast: Luis Gerardo Mendez, Miguel Rodarte, Andrés Almeida, Cassandra Ciangherotti, Monserrat Marañon, R.J. Mitte. World Premiere

Time Share (Tiempo Compartido) / Mexico, Netherlands (Director: Sebastián Hofmann, Screenwriters: Julio Chavezmontes, Sebastián Hofmann, Producer: Julio Chavezmontes) — Two haunted family men join forces in a destructive crusade to rescue their families from a tropical paradise, after becoming convinced that an American timeshare conglomerate has a sinister plan to take their loved ones away. Cast: Luis Gerardo Mendez, Miguel Rodarte, Andrés Almeida, Cassandra Ciangherotti, Monserrat Marañon, R.J. Mitte. World Premiere

Un Traductor / Canada, Cuba (Directors: Rodrigo Barriuso, Sebastián Barriuso, Screenwriter: Lindsay Gossling, Producers: Sebastián Barriuso, Lindsay Gossling) — A Russian Literature professor at the University of Havana is ordered to work as a translator for child victims of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster when they are sent to Cuba for medical treatment. Based on a true story. Cast: Rodrigo Santoro, Maricel Álvarez, Yoandra Suárez. World Premiere

Yardie / United Kingdom (Director: Idris Elba, Screenwriters: Brock Norman Brock, Martin Stellman, Producers: Gina Carter, Robin Gutch) — Jamaica, 1973. When a young boy witnesses his brother’s assassination, a powerful Don gives him a home. Ten years later he is sent on a mission to London. He reunites with his girlfriend and their daughter, but then the past catches up with them. Based on Victor Headley’s novel. Cast: Aml Ameen, Shantol Jackson, Stephen Graham, Fraser James, Sheldon Shepherd, Everaldo Cleary. World Premiere

WORLD CINEMA DOCUMENTARY COMPETITION

Twelve documentaries by some of the most courageous and extraordinary international filmmakers working today. Films that have premiered in this category in recent years include Motherland, Last Men in Aleppo, Joshua: Teenager vs Superpower and Hooligan Sparrow.

A Polar Year / France (Director: Samuel Collardey, Screenwriters: Samuel Collardey, Catherine Paillé, Producer: Grégoire Debailly) — Anders leaves his native Denmark for a teaching position in rural Greenland. As soon as he arrives, he finds himself at odds with tightly-knit locals. Only through a clumsy and playful trial of errors can Anders shake his Euro-centric assumptions and embrace their snow-covered way of life. Cast: Anders Hvidegaard, Asser Boassen, Julius B. Nielsen, Tobias Ignatiussen, Thomasine Jonathansen, Gert Jonathansen. World Premiere

Anote’s Ark / Canada (Director: Matthieu Rytz, Producers: Bob Moore, Mila Aung-Thwin, Daniel Cross, Shari Plummer, Shannon Joy) — How does a nation survive being swallowed by the sea? Kiribati, on a low-lying Pacific atoll, will disappear within decades due to rising sea levels, population growth, and climate change. This exploration of how to migrate an entire nation with dignity interweaves personal stories of survival and resilience. World Premiere. THE NEW CLIMATE

The Cleaners / Germany, Brazil (Directors: Moritz Riesewieck, Hans Block, Screenwriters: Moritz Riesewieck, Hans Block, Georg Tschurtschenthaler, Producers: Christian Beetz, Georg Tschurtschenthaler, Julie Goldman, Christopher Clements, Fernando Dias, Mauricio Dias) — When you post something on the web, can you be sure it stays there? Enter a hidden shadow industry of digital cleaning, where the Internet rids itself of what it doesn’t like: violence, pornography and political content. Who is controlling what we see…and what we think? World Premiere

Genesis 2.0 / Switzerland (Directors: Christian Frei, Maxim Arbugaev, Producer: Christian Frei) — On the remote New Siberian Islands in the Arctic Ocean, hunters search for tusks of extinct mammoths. When they discover a surprisingly well-preserved mammoth carcass, its resurrection will be the first manifestation of the next great technological revolution: genetics. It may well turn our world upside down. World Premiere

Genesis 2.0 / Switzerland (Directors: Christian Frei, Maxim Arbugaev, Producer: Christian Frei) — On the remote New Siberian Islands in the Arctic Ocean, hunters search for tusks of extinct mammoths. When they discover a surprisingly well-preserved mammoth carcass, its resurrection will be the first manifestation of the next great technological revolution: genetics. It may well turn our world upside down. World Premiere

MATANGI / MAYA / M.I.A. / Sri Lanka, United Kingdom, U.S.A. (Director: Stephen Loveridge, Producers: Lori Cheatle, Andrew Goldman, Paul Mezey) — Drawn from a never before seen cache of personal footage spanning decades, this is an intimate portrait of the Sri Lankan artist and musician who continues to shatter conventions. World Premiere

MATANGI / MAYA / M.I.A. / Sri Lanka, United Kingdom, U.S.A. (Director: Stephen Loveridge, Producers: Lori Cheatle, Andrew Goldman, Paul Mezey) — Drawn from a never before seen cache of personal footage spanning decades, this is an intimate portrait of the Sri Lankan artist and musician who continues to shatter conventions. World Premiere

The Oslo Diaries / Israel, Canada (Directors and screenwriters: Mor Loushy, Daniel Sivan, Producers: Hilla Medalia, Ina Fichman) — In 1992, Israeli-Palestinian relations reached an all time low. In an attempt to stop the bloodshed, a group of Israelis and Palestinians met illegally in Oslo. These meetings were never officially sanctioned and held in complete secrecy. They changed the Middle East forever. World Premiere

Our New President / Russia, U.S.A. (Director: Maxim Pozdorovkin, Producers: Maxim Pozdorovkin, Joe Bender) — The story of Donald Trump’s election told entirely through Russian propaganda. By turns horrifying and hilarious, the film is a satirical portrait of Russian media that reveals an empire of fake news and the tactics of modern-day information warfare. World Premiere.

Our New President / Russia, U.S.A. (Director: Maxim Pozdorovkin, Producers: Maxim Pozdorovkin, Joe Bender) — The story of Donald Trump’s election told entirely through Russian propaganda. By turns horrifying and hilarious, the film is a satirical portrait of Russian media that reveals an empire of fake news and the tactics of modern-day information warfare. World Premiere.

Westwood / United Kingdom (Director: Lorna Tucker, Producers: Eleanor Emptage, Shirine Best, Nicole Stott, John Battsek) — Dame Vivienne Westwood: punk, icon, provocateur and one of the most influential originators in recent history. This is the first film to encompass the remarkable story of one of the true icons of our time, as she fights to maintain her brand’s integrity, her principles – and her legacy. World Premiere

A Woman Captured / Hungary (Director and screenwriter: Bernadett Tuza-Ritter, Producers: Julianna Ugrin, Viki Réka Kiss, Erik Winker, Martin Roelly) — A European woman has been kept by a family as a domestic slave for 10 years – one of over 45 million victims of modern-day slavery. Drawing courage from the filmmaker’s presence, she decides to escape the unbearable oppression and become a free person. North American Premiere

A Woman Captured / Hungary (Director and screenwriter: Bernadett Tuza-Ritter, Producers: Julianna Ugrin, Viki Réka Kiss, Erik Winker, Martin Roelly) — A European woman has been kept by a family as a domestic slave for 10 years – one of over 45 million victims of modern-day slavery. Drawing courage from the filmmaker’s presence, she decides to escape the unbearable oppression and become a free person. North American Premiere

NEXT

Pure, bold works distinguished by an innovative, forward-thinking approach to storytelling populate this program. Digital technology paired with unfettered creativity promises that the films in this section will shape a “greater” next wave in American cinema. Films that have premiered in this category in recent years include A Ghost Story, Tangerine and A Girl Walks Home Alone At Night. Presented by Adobe.

306 Hollywood / U.S.A., Hungary (Directors: Elan Bogarín, Jonathan Bogarín, Screenwriters: Jonathan Bogarín, Elan Bogarín, Nyneve Laura Minnear, Producers: Elan Bogarín, Jonathan Bogarín, Judit Stalter) — When two siblings undertake an archaeological excavation of their late grandmother’s house, they embark on a magical-realist journey from her home in New Jersey to ancient Rome, from fashion to physics, in search of what life remains in the objects we leave behind. World Premiere. DAY ONE

306 Hollywood / U.S.A., Hungary (Directors: Elan Bogarín, Jonathan Bogarín, Screenwriters: Jonathan Bogarín, Elan Bogarín, Nyneve Laura Minnear, Producers: Elan Bogarín, Jonathan Bogarín, Judit Stalter) — When two siblings undertake an archaeological excavation of their late grandmother’s house, they embark on a magical-realist journey from her home in New Jersey to ancient Rome, from fashion to physics, in search of what life remains in the objects we leave behind. World Premiere. DAY ONE

A Boy, A Girl, A Dream. / U.S.A. (Director: Qasim Basir, Screenwriters: Qasim Basir, Samantha Tanner, Producer: Datari Turner) — On the night of the 2016 Presidential election, Cass, an L.A. club promoter, takes a thrilling and emotional journey with Frida, a Midwestern visitor. She challenges him to revisit his broken dreams – while he pushes her to discover hers. Cast: Omari Hardwick, Meagan Good, Jay Ellis, Kenya Barris, Dijon Talton, Wesley Jonathan. World Premiere

A Boy, A Girl, A Dream. / U.S.A. (Director: Qasim Basir, Screenwriters: Qasim Basir, Samantha Tanner, Producer: Datari Turner) — On the night of the 2016 Presidential election, Cass, an L.A. club promoter, takes a thrilling and emotional journey with Frida, a Midwestern visitor. She challenges him to revisit his broken dreams – while he pushes her to discover hers. Cast: Omari Hardwick, Meagan Good, Jay Ellis, Kenya Barris, Dijon Talton, Wesley Jonathan. World Premiere

An Evening With Beverly Luff Linn / United Kingdom, U.S.A. (Director: Jim Hosking, Screenwriters: Jim Hosking, David Wike, Producers: Sam Bisbee, Theodora Dunlap, Oliver Roskill, Emily Leo, Lucan Toh, Andy Starke) — Lulu Danger’s unsatisfying marriage takes a fortunate turn for the worse when a mysterious man from her past comes to town to perform an event called ‘An Evening With Beverly Luff Linn For One Magical Night Only.’ Cast: Aubrey Plaza, Emile Hirsch, Jemaine Clement, Matt Berry, Craig Robinson. World Premiere

Clara’s Ghost / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Bridey Elliott, Producer: Sarah Winshall) — Set over the course of a single evening at the Reynolds’ family home in Connecticut, Clara, fed up with the constant ribbing from her self-absorbed showbiz family, finds solace in and guidance from the supernatural force she believes is haunting her. Cast: Paula Niedert Elliott, Chris Elliott, Abby Elliott, Bridey Elliott, Haley Joel Osment, Isidora Goreshter. World Premiere

Clara’s Ghost / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Bridey Elliott, Producer: Sarah Winshall) — Set over the course of a single evening at the Reynolds’ family home in Connecticut, Clara, fed up with the constant ribbing from her self-absorbed showbiz family, finds solace in and guidance from the supernatural force she believes is haunting her. Cast: Paula Niedert Elliott, Chris Elliott, Abby Elliott, Bridey Elliott, Haley Joel Osment, Isidora Goreshter. World Premiere

Madeline’s Madeline / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Josephine Decker, Producers: Krista Parris, Elizabeth Rao) — Madeline got the part! She’s going to play the lead in a theater piece! Except the lead wears sweatpants like Madeline’s. And has a cat like Madeline’s. And is holding a steaming hot iron next to her mother’s face – like Madeline is. Cast: Helena Howard, Molly Parker, Miranda July, Okwui Okpokwasili, Felipe Bonilla, Lisa Tharps. World Premiere

Night Comes On / U.S.A. (Director: Jordana Spiro, Screenwriters: Jordana Spiro, Angelica Nwandu, Producers: Jonathan Montepare, Alvaro R. Valente, Danielle Renfrew Behrens) — Angel LaMere is released from juvenile detention on the eve of her 18th birthday. Haunted by her past, she embarks on a journey with her 10 year-old sister that could destroy their future. Cast: Dominique Fishback, Tatum Hall, John Earl Jelks, Max Casella, James McDaniel. World Premiere

Skate Kitchen / U.S.A. (Director: Crystal Moselle, Screenwriters: Crystal Moselle, Ashlihan Unaldi, Producers: Lizzie Nastro, Izabella Tzenkova, Julia Nottingham, Matthew Perniciaro, Michael Sherman, Rodrigo Teixeira) — Camille’s life as a lonely suburban teenager changes dramatically when she befriends a group of girl skateboarders. As she journeys deeper into this raw New York City subculture, she begins to understand the true meaning of friendship as well as her inner self. Cast: Rachelle Vinberg, Dede Lovelace, Jaden Smith, Nina Moran, Ajani Russell, Kabrina Adams. World Premiere

Skate Kitchen / U.S.A. (Director: Crystal Moselle, Screenwriters: Crystal Moselle, Ashlihan Unaldi, Producers: Lizzie Nastro, Izabella Tzenkova, Julia Nottingham, Matthew Perniciaro, Michael Sherman, Rodrigo Teixeira) — Camille’s life as a lonely suburban teenager changes dramatically when she befriends a group of girl skateboarders. As she journeys deeper into this raw New York City subculture, she begins to understand the true meaning of friendship as well as her inner self. Cast: Rachelle Vinberg, Dede Lovelace, Jaden Smith, Nina Moran, Ajani Russell, Kabrina Adams. World Premiere

We The Animals / U.S.A. (Director: Jeremiah Zagar, Screenwriters: Daniel Kitrosser, Jeremiah Zagar, Producers: Jeremy Yaches, Christina D. King, Andrew Goldman, Paul Mezey) — Us three, us brothers, us kings. Manny, Joel and Jonah tear their way through childhood and push against the volatile love of their parents. As Manny and Joel grow into versions of their father and Ma dreams of escape, Jonah, the youngest, embraces an imagined world all his own. Cast: Raul Castillo, Sheila Vand, Evan Rosado, Isaiah Kristian, Josiah Santiago. World Premiere

We The Animals / U.S.A. (Director: Jeremiah Zagar, Screenwriters: Daniel Kitrosser, Jeremiah Zagar, Producers: Jeremy Yaches, Christina D. King, Andrew Goldman, Paul Mezey) — Us three, us brothers, us kings. Manny, Joel and Jonah tear their way through childhood and push against the volatile love of their parents. As Manny and Joel grow into versions of their father and Ma dreams of escape, Jonah, the youngest, embraces an imagined world all his own. Cast: Raul Castillo, Sheila Vand, Evan Rosado, Isaiah Kristian, Josiah Santiago. World Premiere

White Rabbit / U.S.A. (Director: Daryl Wein, Screenwriters: Daryl Wein, Vivian Bang, Producers: Daryl Wein, Vivian Bang) —A dramatic comedy following a Korean American performance artist who struggles to be authentically heard and seen through her multiple identities in modern Los Angeles. Cast: Vivian Bang, Nana Ghana, Nico Evers-Swindel, Tracy Hazas, Elizabeth Sung, Michelle Sui. World Premiere

White Rabbit / U.S.A. (Director: Daryl Wein, Screenwriters: Daryl Wein, Vivian Bang, Producers: Daryl Wein, Vivian Bang) —A dramatic comedy following a Korean American performance artist who struggles to be authentically heard and seen through her multiple identities in modern Los Angeles. Cast: Vivian Bang, Nana Ghana, Nico Evers-Swindel, Tracy Hazas, Elizabeth Sung, Michelle Sui. World Premiere

PREMIERES

A showcase of world premieres of some of the most highly anticipated narrative films of the coming year. Films that have premiered in this category in recent years include The Big Sick, Call Me By Your Name, Boyhood and Mudbound.

The Long Dumb Road / U.S.A. (Director: Hannah Fidell, Screenwriters: Hannah Fidell, Carson Mell, Producers: Hannah Fidell, Jacqueline “JJ” Ingram, Jonathan Duffy, Kelly Williams) — Two very different men, at personal crossroads, meet serendipitously and take an unpredictable journey through the American Southwest. Cast: Tony Revolori, Jason Mantzoukas, Taissa Farmiga, Grace Gummer, Ron Livingston, Casey Wilson, Ciara Bravo. World Premiere

Private Life / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Tamara Jenkins, Producers: Anthony Bregman, Stefanie Azpiazu) — A couple in the throes of infertility try to maintain their marriage as they descend deeper into the weird world of assisted reproduction and domestic adoption. When their doctor suggests third-party reproduction, they bristle. But when Sadie, a recent college dropout, re-enters their life, they reconsider. Cast: Kathryn Hahn, Paul Giamatti, Molly Shannon, John Carroll Lynch, Kayli Carter. World Premiere

Private Life / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Tamara Jenkins, Producers: Anthony Bregman, Stefanie Azpiazu) — A couple in the throes of infertility try to maintain their marriage as they descend deeper into the weird world of assisted reproduction and domestic adoption. When their doctor suggests third-party reproduction, they bristle. But when Sadie, a recent college dropout, re-enters their life, they reconsider. Cast: Kathryn Hahn, Paul Giamatti, Molly Shannon, John Carroll Lynch, Kayli Carter. World Premiere

A Kid Like Jake / U.S.A. (Director: Silas Howard, Screenwriter: Daniel Pearle, Producers: Jim Parsons, Todd Spiewak, Eric Norsoph, Paul Bernon, Rachel Song) — As married couple Alex and Greg navigate their roles as parents to a young son who prefers Cinderella to G.I. Joe, a rift grows between them, one that forces them to confront their own concerns about what’s best for their child, and each other. Cast: Claire Danes, Jim Parsons, Octavia Spencer, Priyanka Chopra, Ann Dowd, Amy Landecker. World Premiere

Beirut / U.S.A. (Director: Brad Anderson, Screenwriter: Tony Gilroy) — A U.S. diplomat flees Lebanon in 1972 after a tragic incident at his home. Ten years later, he is called back to war-torn Beirut by CIA operatives to negotiate for the life of a friend he left behind. Cast: Jon Hamm, Rosamund Pike, Shea Whigham, Dean Norris. World Premiere

The Catcher Was a Spy / U.S.A. (Director: Ben Lewin, Screenwriter: Robert Rodat, Producers: Kevin Frakes, Tatiana Kelly, Buddy Patrick, Jim Young) — The true story of Moe Berg – professional baseball player, Ivy League graduate, attorney who spoke nine languages – and a top-secret spy for the OSS who helped the U.S. win the race against Germany to build the atomic bomb. Cast: Paul Rudd, Mark Strong, Sienna Miller, Jeff Daniels, Guy Pearce, Paul Giamatti. World Premiere

Colette / United Kingdom (Director: Wash Westmoreland, Screenwriters: Wash Westmoreland, Richard Glatzer, Producers: Pamela Koffler, Christine Vachon, Elizabeth Karlsen, Stephen Woolley) — A young country woman marries a famous literary entrepreneur in turn-of-the-century Paris: At her husband’s request, Colette pens a series of bestselling novels published under his name. But as her confidence grows, she transforms not only herself and her marriage, but the world around her. Cast: Keira Knightley, Dominic West, Fiona Shaw, Denise Gough, Elinor Tomlinson, Aiysha Hart. World Premiere

Colette / United Kingdom (Director: Wash Westmoreland, Screenwriters: Wash Westmoreland, Richard Glatzer, Producers: Pamela Koffler, Christine Vachon, Elizabeth Karlsen, Stephen Woolley) — A young country woman marries a famous literary entrepreneur in turn-of-the-century Paris: At her husband’s request, Colette pens a series of bestselling novels published under his name. But as her confidence grows, she transforms not only herself and her marriage, but the world around her. Cast: Keira Knightley, Dominic West, Fiona Shaw, Denise Gough, Elinor Tomlinson, Aiysha Hart. World Premiere

Come Sunday / U.S.A. (Director: Joshua Marston, Screenwriter: Marcus Hinchey, Producers: Ira Glass, Alissa Shipp, Julie Goldstein, James Stern, Lucas Smith, Cindy Kirven) — Internationally-renowned pastor Carlton Pearson — experiencing a crisis of faith — risks his church, family and future when he questions church doctrine and finds himself branded a modern-day heretic. Based on actual events. Cast: Chiwetel Ejiofor, Danny Glover, Condola Rashad, Jason Segel, Lakeith Stanfield, Martin Sheen. World Premiere

Damsel / U.S.A. (Directors and screenwriters: David Zellner, Nathan Zellner, Producers: Nathan Zellner, Chris Ohlson, David Zellner) — Samuel Alabaster, an affluent pioneer, ventures across the American Frontier to marry the love of his life, Penelope. As Samuel, a drunkard named Parson Henry and a miniature horse called Butterscotch traverse the Wild West, their once-simple journey grows treacherous, blurring the lines between hero, villain and damsel. Cast: Robert Pattinson, Mia Wasikowska, David Zellner, Robert Forster, Nathan Zellner, Joe Billingiere. World Premiere

Damsel / U.S.A. (Directors and screenwriters: David Zellner, Nathan Zellner, Producers: Nathan Zellner, Chris Ohlson, David Zellner) — Samuel Alabaster, an affluent pioneer, ventures across the American Frontier to marry the love of his life, Penelope. As Samuel, a drunkard named Parson Henry and a miniature horse called Butterscotch traverse the Wild West, their once-simple journey grows treacherous, blurring the lines between hero, villain and damsel. Cast: Robert Pattinson, Mia Wasikowska, David Zellner, Robert Forster, Nathan Zellner, Joe Billingiere. World Premiere

Don’t Worry, He Won’t Get Far On Foot / U.S.A. (Director: Gus Van Sant, Screenwriters: Gus Van Sant (screenplay), John Callahan (biography), Producers: Charles-Marie Anthonioz, Mourad Belkeddar, Steve Golin, Nicolas Lhermitte) — John Callahan has a talent for off-color jokes…and a drinking problem. When a bender ends in a car accident, Callahan wakes permanently confined to a wheelchair. In his journey back from rock bottom, Callahan finds beauty and comedy in the absurdity of human experience. Cast: Joaquin Phoenix, Jonah Hill, Rooney Mara, Jack Black. World Premiere

Don’t Worry, He Won’t Get Far On Foot / U.S.A. (Director: Gus Van Sant, Screenwriters: Gus Van Sant (screenplay), John Callahan (biography), Producers: Charles-Marie Anthonioz, Mourad Belkeddar, Steve Golin, Nicolas Lhermitte) — John Callahan has a talent for off-color jokes…and a drinking problem. When a bender ends in a car accident, Callahan wakes permanently confined to a wheelchair. In his journey back from rock bottom, Callahan finds beauty and comedy in the absurdity of human experience. Cast: Joaquin Phoenix, Jonah Hill, Rooney Mara, Jack Black. World Premiere

Futile and Stupid Gesture / U.S.A. (Director: David Wain, Screenwriters: John Aboud, Michael Colton, Producers: Peter Principato, Jonathan Stern) — The story of comedy wunderkind Doug Kenney, who co-created the National Lampoon, Caddyshack, and Animal House. Kenney was at the center of the 70’s comedy counter-culture which gave birth to Saturday Night Live and a whole generation’s way of looking at the world. Cast: Will Forte, Martin Mull, Domhnall Gleeson, Matt Walsh, Joel McHale, Emmy Rossum. World Premiere

Futile and Stupid Gesture / U.S.A. (Director: David Wain, Screenwriters: John Aboud, Michael Colton, Producers: Peter Principato, Jonathan Stern) — The story of comedy wunderkind Doug Kenney, who co-created the National Lampoon, Caddyshack, and Animal House. Kenney was at the center of the 70’s comedy counter-culture which gave birth to Saturday Night Live and a whole generation’s way of looking at the world. Cast: Will Forte, Martin Mull, Domhnall Gleeson, Matt Walsh, Joel McHale, Emmy Rossum. World Premiere

The Happy Prince / Germany, Belgium, Italy (Director and screenwriter: Rupert Everett) — The last days of Oscar Wilde—and the ghosts haunting them—are brought to vivid life. His body ailing, Wilde lives in exile, surviving on the flamboyant irony and brilliant wit that defined him as the transience of lust is laid bare and the true riches of love are revealed. Cast: Colin Firth, Emily Watson, Colin Morgan, Edwin Thomas, Rupert Everett. World Premiere

The Happy Prince / Germany, Belgium, Italy (Director and screenwriter: Rupert Everett) — The last days of Oscar Wilde—and the ghosts haunting them—are brought to vivid life. His body ailing, Wilde lives in exile, surviving on the flamboyant irony and brilliant wit that defined him as the transience of lust is laid bare and the true riches of love are revealed. Cast: Colin Firth, Emily Watson, Colin Morgan, Edwin Thomas, Rupert Everett. World Premiere

Hearts Beat Loud / U.S.A. (Director: Brett Haley, Screenwriters: Brett Haley, Marc Basch, Producers: Houston King, Sam Bisbee, Sam Slater) — In Red Hook, Brooklyn, a father and daughter become an unlikely songwriting duo in the last summer before she leaves for college. Cast: Nick Offerman, Kiersey Clemons, Ted Danson, Sasha Lane, Blythe Danner, Toni Collette. World Premiere

Juliet, Naked / United Kingdom (Director: Jesse Peretz, Screenwriters: Tamara Jenkins, Jim Taylor, Phil Alden Robinson, Evgenia Peretz, Producers: Judd Apatow, Barry Mendel, Albert Berger, Ron Yerxa) — Annie is the long-suffering girlfriend of Duncan, an obsessive fan of obscure rocker Tucker Crowe. When the acoustic demo of Tucker’s celebrated record from 25 years ago surfaces, its release leads to an encounter with the elusive rocker himself. Based on the novel by Nick Hornby. Cast: Rose Byrne, Ethan Hawke, Chris O’Dowd. World Premiere

Ophelia / United Kingdom (Director: Claire McCarthy, Screenwriter: Semi Chellas, Producers: Daniel Bobker, Sarah Curtis, Ehren Kruger, Paul Hanson) — A mythic spin on Hamlet through a lens of female empowerment: Ophelia comes of age as lady-in-waiting for Queen Gertrude, and her singular spirit captures Hamlet’s affections. As lust and betrayal threaten the kingdom, Ophelia finds herself trapped between true love and controlling her own destiny. Cast: Daisy Ridley, Naomi Watts, Clive Owen, George MacKay, Tom Felton, Devon Terrell. World Premiere

Ophelia / United Kingdom (Director: Claire McCarthy, Screenwriter: Semi Chellas, Producers: Daniel Bobker, Sarah Curtis, Ehren Kruger, Paul Hanson) — A mythic spin on Hamlet through a lens of female empowerment: Ophelia comes of age as lady-in-waiting for Queen Gertrude, and her singular spirit captures Hamlet’s affections. As lust and betrayal threaten the kingdom, Ophelia finds herself trapped between true love and controlling her own destiny. Cast: Daisy Ridley, Naomi Watts, Clive Owen, George MacKay, Tom Felton, Devon Terrell. World Premiere

Puzzle / U.S.A. (Director: Marc Turtletaub, Screenwriter: Oren Moverman, Producers: Peter Saraf, Wren Arthur, Guy Stodel) — Agnes, taken for granted as a suburban mother, discovers a passion for solving jigsaw puzzles which unexpectedly draws her into a new world – where her life unfolds in ways she could never have imagined. Cast: Kelly Macdonald, Irrfan Khan, David Denman, Bubba Weiler, Austin Abrams, Liv Hewson. World Premiere

Untitled Debra Granik Project / U.S.A. (Director: Debra Granik, Screenwriters: Debra Granik, Anne Rosellini, Producers: Anne Harrison, Linda Reisman, Anne Rosellini) — A father and daughter live a perfect but mysterious existence in Forest Park, a beautiful nature reserve near Portland, Oregon, rarely making contact with the world. A small mistake tips them off to authorities sending them on an increasingly erratic journey in search of a place to call their own. Cast: Ben Foster, Thomasin Harcourt McKenzie, Jeff Korber, Dale Dickey. World Premiere

What They Had / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Elizabeth Chomko) — Bridget returns home to Chicago at her brother’s urging to deal with her mother’s Alzheimer’s and her father’s reluctance to let go of their life together. Cast: Hilary Swank, Michael Shannon, Blythe Danner, Robert Forster. World Premiere

DOCUMENTARY PREMIERES

Renowned filmmakers and films about far-reaching subjects comprise this section highlighting our ongoing commitment to documentaries. Films that have premiered in this category in recent years include An Inconvenient Sequel, The Hunting Ground, Going Clear and What Happened, Miss Simone?

Akicita: The Battle of Standing Rock / U.S.A. (Director: Cody Lucich, Producers: Heather Rae, Gingger Shankar, Ben-Alex Dupris) — Standing Rock, 2016: the largest Native American occupation since Wounded Knee. Thousands of activists, environmentalists and militarized police descend on the Dakota Access Pipeline in a standoff between oil corporations and a new generation of Native Warriors. This chronicle captures the sweeping struggle, spirit and havoc of a People’s uprising. World Premiere. THE NEW CLIMATE

Bad Reputation / U.S.A. (Director: Kevin Kerslake, Screenwriter: Joel Marcus, Producers: Peter Afterman, Carianne Brinkman) — A look at the life of Joan Jett, from her early years as the founder of The Runaways and first meeting collaborator Kenny Laguna in 1980 to her enduring presence in pop culture as a rock ‘n’ roll pioneer . World Premiere

Believer / U.S.A. (Director: Don Argott, Producers: Heather Parry, Sheena M. Joyce, Robert Reynolds) — Imagine Dragons’ Mormon frontman Dan Reynolds is taking on a new mission to explore how the church treats its LGBTQ members. With the rising suicide rate amongst teens in the state of Utah, his concern with the church’s policies sends him on an unexpected path for acceptance and change. World Premiere

Chef Flynn / U.S.A. (Director: Cameron Yates, Producer: Laura Coxson) — Ten-year-old Flynn transforms his living room into a supper club, using his classmates as line cooks and serving a tasting menu foraged from his neighbors’ backyards. With sudden fame, Flynn outgrows his bedroom kitchen and mother’s camera, and sets out to challenge the hierarchy of the culinary world. World Premiere

Chef Flynn / U.S.A. (Director: Cameron Yates, Producer: Laura Coxson) — Ten-year-old Flynn transforms his living room into a supper club, using his classmates as line cooks and serving a tasting menu foraged from his neighbors’ backyards. With sudden fame, Flynn outgrows his bedroom kitchen and mother’s camera, and sets out to challenge the hierarchy of the culinary world. World Premiere

The Game Changers / U.S.A. (Director: Louie Psihoyos, Screenwriters: Mark Monroe, Joseph Pace, Producers: Joseph Pace, James Wilks) — James Wilks, an elite special forces trainer and winner of The Ultimate Fighter, embarks on a quest for the truth in nutrition and uncovers the world’s most dangerous myth. World Premiere

Generation Wealth / U.S.A. (Director: Lauren Greenfield, Producers: Lauren Greenfield, Frank Evers) — Lauren Greenfield’s postcard from the edge of the American Empire captures a portrait of a materialistic, image-obsessed culture. Simultaneously personal journey and historical essay, the film bears witness to the global boom–bust economy, the corrupted American Dream and the human costs of late stage capitalism, narcissism and greed. World Premiere. DAY ONE

Generation Wealth / U.S.A. (Director: Lauren Greenfield, Producers: Lauren Greenfield, Frank Evers) — Lauren Greenfield’s postcard from the edge of the American Empire captures a portrait of a materialistic, image-obsessed culture. Simultaneously personal journey and historical essay, the film bears witness to the global boom–bust economy, the corrupted American Dream and the human costs of late stage capitalism, narcissism and greed. World Premiere. DAY ONE

Half The Picture / U.S.A. (Director: Amy Adrion, Producers: Amy Adrion, David Harris) — At a pivotal moment for gender equality in Hollywood, successful women directors tell the stories of their art, lives and careers. Having endured a long history of systemic discrimination, women filmmakers may be getting the first glimpse of a future that values their voices equally. World Premiere

Jane Fonda in Five Acts / U.S.A. (Director: Susan Lacy, Producers: Susan Lacy, Jessica Levin, Emma Pildes) — Girl next door, activist, so-called traitor, fitness tycoon, Oscar winner: Jane Fonda has lived a life of controversy, tragedy and transformation – and she’s done it all in the public eye. An intimate look at one woman’s singular journey. World Premiere

King In The Wilderness / U.S.A. (Director: Peter Kunhardt, Producers: George Kunhardt, Teddy Kunhardt) From the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965 to his assassination in 1968, Martin Luther King, Jr. remained a man with an unshakeable commitment to nonviolence in the face of an increasingly unstable country. A portrait of the last years of his life. World Premiere

Quiet Heroes / U.S.A. (Director: Jenny Mackenzie, Co-Directors: Jared Ruga, Amanda Stoddard, Producers: Jenny Mackenzie, Jared Ruga, Amanda Stoddard) — In Salt Lake City, Utah, the socially conservative religious monoculture complicated the AIDS crisis, where patients in the entire state and intermountain region relied on only one doctor. This is the story of her fight to save a maligned population everyone else seemed willing to just let die. World Premiere

Quiet Heroes / U.S.A. (Director: Jenny Mackenzie, Co-Directors: Jared Ruga, Amanda Stoddard, Producers: Jenny Mackenzie, Jared Ruga, Amanda Stoddard) — In Salt Lake City, Utah, the socially conservative religious monoculture complicated the AIDS crisis, where patients in the entire state and intermountain region relied on only one doctor. This is the story of her fight to save a maligned population everyone else seemed willing to just let die. World Premiere

RBG / U.S.A. (Directors and producers: Betsy West, Julie Cohen) — An intimate portrait of an unlikely rock star: Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. With unprecedented access, the filmmakers show how her early legal battles changed the world for women. Now this 84-year-old does push-ups as easily as she writes blistering dissents that have earned her the title “Notorious RBG.” World Premiere

Robin Williams: Come Inside My Mind / U.S.A. (Director: Marina Zenovich, Producers: Alex Gibney, Shirel Kozak) — This intimate portrait examines one of the world’s most beloved and inventive comedians. Told largely through Robin’s own voice and using a wealth of never-before-seen archive, the film takes us through his extraordinary life and career and reveals the spark of madness that drove him. World Premiere

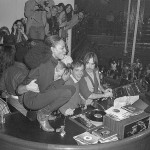

STUDIO 54 / U.S.A. (Director: Matt Tyrnauer, Producers: Matt Tyrnauer, John Battsek, Corey Reeser) — Studio 54 was the pulsating epicenter of 1970s hedonism: a disco hothouse of beautiful people, drugs, and sex. The journeys of Ian Schrager and Steve Rubell — two best friends from Brooklyn who conquered New York City — frame this history of the “greatest club of all time.” World Premiere

STUDIO 54 / U.S.A. (Director: Matt Tyrnauer, Producers: Matt Tyrnauer, John Battsek, Corey Reeser) — Studio 54 was the pulsating epicenter of 1970s hedonism: a disco hothouse of beautiful people, drugs, and sex. The journeys of Ian Schrager and Steve Rubell — two best friends from Brooklyn who conquered New York City — frame this history of the “greatest club of all time.” World Premiere

Won’t You Be My Neighbor? / U.S.A. (Director: Morgan Neville, Producers: Caryn Capotosto, Nicholas Ma) — Fred Rogers used puppets and play to explore complex social issues: race, disability, equality and tragedy, helping form the American concept of childhood. He spoke directly to children and they responded enthusiastically. Yet today, his impact is unclear. Have we lived up to Fred’s ideal of good neighbors? World Premiere. SALT LAKE CITY OPENING NIGHT FILM

MIDNIGHT

From horror and comedy to works that defy genre classification, these films will keep you wide awake, even at the most arduous hour. Films that have premiered in this category in recent years include The Little Hours, The Babadook and Get Out.

Arizona / U.S.A. (Director: Jonathan Watson, Screenwriter: Luke Del Tredici, Producers: Dan Friedkin, Bradley Thomas, Ryan Friedkin, Danny McBride, Brandon James) — Set in the midst of the 2009 housing crisis, this darkly comedic story follows Cassie Fowler, a single mom and struggling realtor whose life goes off the rails when she witnesses a murder. Cast: Danny McBride, Rosemarie DeWitt, Luke Wilson, Lolli Sorenson, Elizabeth Gillies, Kaitlin Olson. World Premiere

Assassination Nation / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Sam Levinson, Producers: David Goyer, Anita Gou, Kevin Turen, Aaron L. Gilbert, Matthew J. Malek) — This is a one-thousand-percent true story about how the quiet, all-American town of Salem, Massachusetts, absolutely lost its mind. Cast: Odessa Young, Suki Waterhouse, Hari Nef, Abra, Bill Skarsgard, Bella Thorne. World Premiere

Mandy / Belgium, U.S.A. (Director: Panos Cosmatos, Screenwriters: Panos Cosmatos, Aaron Stewart-Ahn, Producers: Daniel Noah, Josh Waller, Elijah Wood, Nate Bolotin, Adrian Politowski) — Pacific Northwest. 1983 AD. Outsiders Red Miller and Mandy Bloom lead a loving and peaceful existence. When their pine-scented haven is savagely destroyed by a cult led by the sadistic Jeremiah Sand, Red is catapulted into a phantasmagoric journey filled with bloody vengeance and laced with fire. Cast: Nicolas Cage, Andrea Riseborough, Linus Roache, Olwen Fouéré, Richard Brake, Bill Duke. World Premiere

Mandy / Belgium, U.S.A. (Director: Panos Cosmatos, Screenwriters: Panos Cosmatos, Aaron Stewart-Ahn, Producers: Daniel Noah, Josh Waller, Elijah Wood, Nate Bolotin, Adrian Politowski) — Pacific Northwest. 1983 AD. Outsiders Red Miller and Mandy Bloom lead a loving and peaceful existence. When their pine-scented haven is savagely destroyed by a cult led by the sadistic Jeremiah Sand, Red is catapulted into a phantasmagoric journey filled with bloody vengeance and laced with fire. Cast: Nicolas Cage, Andrea Riseborough, Linus Roache, Olwen Fouéré, Richard Brake, Bill Duke. World Premiere

Never Goin’ Back / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Augustine Frizzell, Producers: Toby Halbrooks, Liz Cardenas , James Johnston, David Lowery) — Jessie and Angela, high school dropout BFFs, are taking a week off to chill at the beach. Too bad their house got robbed, rent’s due, they’re about to get fired and they’re broke. Now they’ve gotta avoid eviction, stay out of jail and get to the beach, no matter what!!! Cast: Maia Mitchell, Cami Morrone, Kyle Mooney, Joel Allen, Kendal Smith, Matthew Holcomb. World Premiere

Piercing / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Nicolas Pesce, Producers: Josh Mond, Antonio Campos, Schuyler Weiss, Jake Wasserman) — In this twisted love story, a man seeks out an unsuspecting stranger to help him purge the dark torments of his past. His plan goes awry when he encounters a woman with plans of her own. A playful psycho-thriller game of cat-and-mouse based on Ryu Murakami’s novel. Cast: Christopher Abbott, Mia Wasikowska, Laia Costa, Marin Ireland, Maria Dizzia, Wendell Pierce. World Premiere

Revenge / France (Director and screenwriter: Coralie Fargeat, Producers: Marc-Etienne Schwartz, Jean-Yves Robin, Marc Stanimirovic) — Three wealthy married men get together for their annual hunting game in a desert canyon. This time, one of them has brought along his young mistress, who quickly arouses the interest of the other two. Things get dramatically out of hand as a hunting game turns into a ruthless manhunt. Cast: Matilda Lutz, Kevin Janssens, Vincent Colombe, Guillaume Bouchede, Jean-Louis Tribes. Utah Premiere

Summer of ’84 / Canada, U.S.A. (Directors: Francois Simard, Anouk Whissell, Yoann Whissell, Screenwriters: Matt Leslie, Stephen J. Smith, Producers: Shawn Williamson, Jameson Parker, Matt Leslie, Van Toffler, Cody Zwieg) — Summer, 1984: a perfect time to be a carefree 15-year-old. But when neighborhood conspiracy theorist Davey Armstrong begins to suspect his police officer neighbor might be the serial killer all over the local news, he and his three best friends begin an investigation that soon turns dangerous. Cast: Graham Verchere, Judah Lewis, Caleb Emery, Cory Grüter-Andrew, Tiera Skovbye, Rich Sommer. World Premiere

Summer of ’84 / Canada, U.S.A. (Directors: Francois Simard, Anouk Whissell, Yoann Whissell, Screenwriters: Matt Leslie, Stephen J. Smith, Producers: Shawn Williamson, Jameson Parker, Matt Leslie, Van Toffler, Cody Zwieg) — Summer, 1984: a perfect time to be a carefree 15-year-old. But when neighborhood conspiracy theorist Davey Armstrong begins to suspect his police officer neighbor might be the serial killer all over the local news, he and his three best friends begin an investigation that soon turns dangerous. Cast: Graham Verchere, Judah Lewis, Caleb Emery, Cory Grüter-Andrew, Tiera Skovbye, Rich Sommer. World Premiere

SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL 2018 | PARK CITY, UTAH | JANUARY 2018 |

Green’s female engineer Sarah is at the heart of Proxima. She is a luminous presence – fragile tough and strangely otherworldly. Given the opportunity to join the European Space Agency’s Mars probe mission along with other seasoned spacemen – including Matt Dillon’s macho but golden-hearted leader – she takes the plunge. What starts out as matter of fact preparation for the long term mission soon becomes a fraught and increasingly affecting exploration of what is means to love, to be a parent, to meet professional goals, and to thrive and appreciate our own planet. Proxima is a ground-breaking and beautiful film as much about our life here on Earth as is about this perilous journey into the unknown.

Green’s female engineer Sarah is at the heart of Proxima. She is a luminous presence – fragile tough and strangely otherworldly. Given the opportunity to join the European Space Agency’s Mars probe mission along with other seasoned spacemen – including Matt Dillon’s macho but golden-hearted leader – she takes the plunge. What starts out as matter of fact preparation for the long term mission soon becomes a fraught and increasingly affecting exploration of what is means to love, to be a parent, to meet professional goals, and to thrive and appreciate our own planet. Proxima is a ground-breaking and beautiful film as much about our life here on Earth as is about this perilous journey into the unknown. Larger and much stranger than life, director/producer Matt Wolf (

Larger and much stranger than life, director/producer Matt Wolf ( Dir.: Georgui Balabanov; Documentary with Christo, Jeanne-Claude, Anani Yavashev; Bulgaria 1996, 72 min.

Dir.: Georgui Balabanov; Documentary with Christo, Jeanne-Claude, Anani Yavashev; Bulgaria 1996, 72 min.

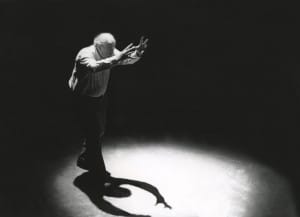

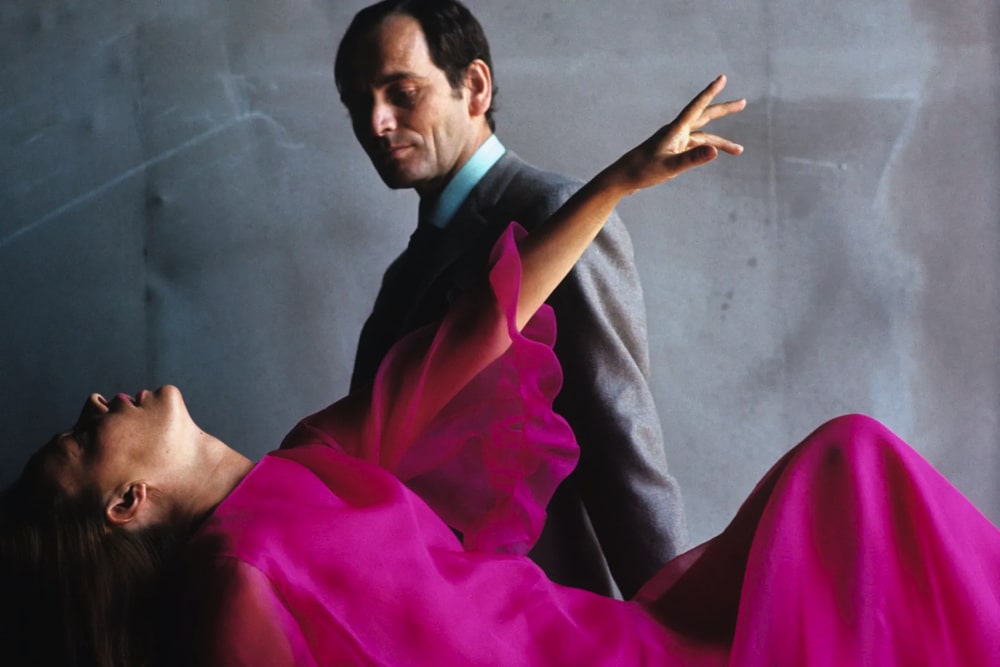

Merce was also passionate about working with artists from other disciplines including composer John Cage, Cunningham’s longterm partner; the painter Robert Rauschenberg; and Andy Warhol whose collaboration is particularly striking in Merce’s 1968 Sci-fi themed dance work Rainforest which featured Warhol’s metallic helium-filled silver balloons (the Silver Clouds) that float around the dancers like something from outer space.

Merce was also passionate about working with artists from other disciplines including composer John Cage, Cunningham’s longterm partner; the painter Robert Rauschenberg; and Andy Warhol whose collaboration is particularly striking in Merce’s 1968 Sci-fi themed dance work Rainforest which featured Warhol’s metallic helium-filled silver balloons (the Silver Clouds) that float around the dancers like something from outer space.

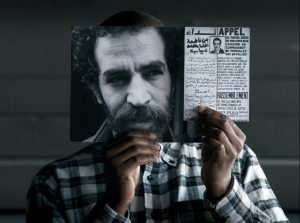

Documentary wise: Ebs Burnough’s The Capote Tapes takes us back through the archives to revisit the iconic American novelist, while Nanni Moretti’s Santiago, Italia (left) explores the Italian role in rescuing exiles out of Chile after Pinochet’s Coup d’Etat.

Documentary wise: Ebs Burnough’s The Capote Tapes takes us back through the archives to revisit the iconic American novelist, while Nanni Moretti’s Santiago, Italia (left) explores the Italian role in rescuing exiles out of Chile after Pinochet’s Coup d’Etat.  Women filmmakers will be also championed in Mark Cousins’ 2018 epic homage to the history of female talent: Women Make Film:

Women filmmakers will be also championed in Mark Cousins’ 2018 epic homage to the history of female talent: Women Make Film:

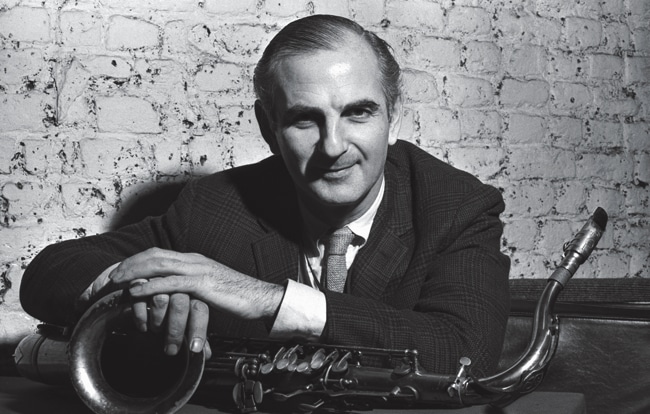

The former artistic director of the Royal Academy Tim Marlow takes us round Lucian Freud’s first and only exhibition at the London gallery (until 26 January 2020). Although Freud is seen as a modern artist his work is very much connected to that ‘old master’, painterly tradition of Titian and Rembrandt: Few modern artists have explored the human body with such intensity, and such determination. Of course, he was a gambler, a playboy and a bon viveur, but few artists spent as much time in their studio as Lucian Freud. The RA’s Andrea Tarsia explains how he pitted his developing style against his personal life, scrutinising himself as much as his subjects. His single-minded passion focused on self-portraiture as much as on those his was painting:. “Everything is a self-portrait”. Often his subjects are not even named: what mattered more to him was the immediacy of the situation, the spontaneity of the gaze. Accompanied by a jazzy score the doc conveys the energy and charisma that seems to spin off each hypnotic portrait, even a small canvas can dominate a room.

The former artistic director of the Royal Academy Tim Marlow takes us round Lucian Freud’s first and only exhibition at the London gallery (until 26 January 2020). Although Freud is seen as a modern artist his work is very much connected to that ‘old master’, painterly tradition of Titian and Rembrandt: Few modern artists have explored the human body with such intensity, and such determination. Of course, he was a gambler, a playboy and a bon viveur, but few artists spent as much time in their studio as Lucian Freud. The RA’s Andrea Tarsia explains how he pitted his developing style against his personal life, scrutinising himself as much as his subjects. His single-minded passion focused on self-portraiture as much as on those his was painting:. “Everything is a self-portrait”. Often his subjects are not even named: what mattered more to him was the immediacy of the situation, the spontaneity of the gaze. Accompanied by a jazzy score the doc conveys the energy and charisma that seems to spin off each hypnotic portrait, even a small canvas can dominate a room. A sensuality entered the artist’s work in the late 1950s and early 1960 where an emphasis on touch starts to appear. This is most noticeable during a trip to Ian Fleming’s Golden Eye when he painted a Flemish style portrait on a small scrap of copper. It sees him putting his finger on his lips and was the start of this sensuous awareness. The 1960s also marked a switch to hog-hair brushes with ‘Man’s Head’ (1963) and the restless associated portraits, smooth backgrounds allowing the face to stand out. Although Freud admired Francis Bacon’s style of working in a gestural way, his own work increasingly gained a more structural, almost architectural element, as he slotted colours together with pasty brushstrokes, trying to make the paint tell the story.

A sensuality entered the artist’s work in the late 1950s and early 1960 where an emphasis on touch starts to appear. This is most noticeable during a trip to Ian Fleming’s Golden Eye when he painted a Flemish style portrait on a small scrap of copper. It sees him putting his finger on his lips and was the start of this sensuous awareness. The 1960s also marked a switch to hog-hair brushes with ‘Man’s Head’ (1963) and the restless associated portraits, smooth backgrounds allowing the face to stand out. Although Freud admired Francis Bacon’s style of working in a gestural way, his own work increasingly gained a more structural, almost architectural element, as he slotted colours together with pasty brushstrokes, trying to make the paint tell the story. Lucian Freud’s large 1993 self-portrait is defiant – he was 71, but still emanated power and excitement; his greatest fear was losing his mind, but he was also concerned about his physical vigour. ‘Benefits Supervisor Sleeping’ (1995) sold in 2008 for 33.6million dollars – the highest price ever paid for a work by a living artist. Freud carried on painting voraciously until his death on 20 July 2011. He was 88. “Being with him was like being plugged into the National Grid for an hour” said one sitter. “Freud was one of the great European painters of the last 500 years. He’s one of those big figures across the centuries, rather than representative of an era or a movement” says Tim Marlow. “Tradition is a big word but Lucian challenged tradition constantly”. Jasper Sharp adds him to a list that goes back to Holbein; Durer; Cranach and Rembrandt. And he goes on: “Freud gives that list a little shuffle, making us look at Rembrandt a bit differently and Holbein a bit differently through his eyes, and through himself”. And that is a remarkable achievement for any artist. MT

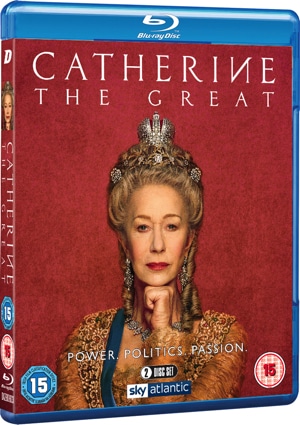

Lucian Freud’s large 1993 self-portrait is defiant – he was 71, but still emanated power and excitement; his greatest fear was losing his mind, but he was also concerned about his physical vigour. ‘Benefits Supervisor Sleeping’ (1995) sold in 2008 for 33.6million dollars – the highest price ever paid for a work by a living artist. Freud carried on painting voraciously until his death on 20 July 2011. He was 88. “Being with him was like being plugged into the National Grid for an hour” said one sitter. “Freud was one of the great European painters of the last 500 years. He’s one of those big figures across the centuries, rather than representative of an era or a movement” says Tim Marlow. “Tradition is a big word but Lucian challenged tradition constantly”. Jasper Sharp adds him to a list that goes back to Holbein; Durer; Cranach and Rembrandt. And he goes on: “Freud gives that list a little shuffle, making us look at Rembrandt a bit differently and Holbein a bit differently through his eyes, and through himself”. And that is a remarkable achievement for any artist. MT Catherine the Great