Kicking off the year in snowy Utah from January 18th – January 28th, Sundance Film Festival is always hotly anticipated amongst the film community. Here’s a selection of what’s on offer in January:

U.S. DRAMATIC COMPETITION

Between the Temples / U.S.A. (Director and Screenwriter: Nathan Silver, Screenwriter: C. Mason Wells, Producers: Tim Headington, Theresa Steele Page, Nate Kamiya, Adam Kersh, Taylor Hess) — A cantor in a crisis of faith finds his world turned upside down when his grade school music teacher reenters his life as his new adult bat mitzvah student. Cast: Jason Schwartzman, Carol Kane, Dolly de Leon, Caroline Aaron, Robert Smigel, Madeline Weinstein. World Premiere. Available online for Public.

Dìdi (弟弟) / U.S.A. (Director, Screenwriter, and Producer: Sean Wang, Producers: Carlos López Estrada, Josh Peters, Valerie Bush) — In 2008, during the last month of summer before high school begins, an impressionable 13-year-old Taiwanese American boy learns what his family can’t teach him: how to skate, how to flirt, and how to love your mom. Cast: Izaac Wang, Joan Chen, Shirley Chen, Chang Li Hua. World Premiere. Available online for Public.

Exhibiting Forgiveness / U.S.A. (Director, Screenwriter, and Producer: Titus Kaphar, Producers: Stephanie Allain, Derek Cianfrance, Jamie Patricof, Sean Cotton) — Utilizing his paintings to find freedom from his past, a Black artist on the path to success is derailed by an unexpected visit from his estranged father, a recovering addict desperate to reconcile. Together, they learn that forgetting might be a greater challenge than forgiving. Cast: André Holland, John Earl Jelks, Andra Day, Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor. World Premiere. Available online for Public.

Good One / U.S.A. (Director, Screenwriter, and Producer: India Donaldson, Producers: Diana Irvine, Graham Mason, Wilson Cameron) — On a weekend backpacking trip in the Catskills, 17-year-old Sam contends with the competing egos of her father and his oldest friend. Cast: Lily Collias, James Le Gros, Danny McCarthy. World Premiere. Available online for Public.

In The Summers / U.S.A. (Director and Screenwriter: Alessandra Lacorazza, Producers: Alexander Dinelaris, Rob Quadrino, Fernando Rodriguez-Vila, Lynette Coll, Sergio Lira, Cristóbal Güell) — On a journey that spans the formative years of their lives, two sisters navigate their loving but volatile father during their yearly summer visits to his home in Las Cruces, New Mexico. Cast: René Pérez Joglar, Sasha Calle, Lío Mehiel, Leslie Grace, Emma Ramos, Sharlene Cruz. World Premiere. Available online for Public.

Love Me / U.S.A. (Directors and Screenwriters: Sam Zuchero, Andy Zuchero, Producers: Kevin Rowe, Luca Borghese, Ben Howe, Shivani Rawat, Julie Goldstein) — Long after humanity’s extinction, a buoy and a satellite meet online and fall in love. Cast: Kristen Stewart, Steven Yeun. World Premiere. Available online for Public.

Ponyboi / U.S.A. (Director: Esteban Arango, Screenwriter: River Gallo, Producers: Mark Ankner, River Gallo, Adel “Future” Nur, Trevor Wall) —Unfolding over the course of Valentine’s Day in New Jersey, a young intersex sex worker must run from the mob after a drug deal goes sideways, forcing him to confront his past. Cast: River Gallo, Dylan O’Brien, Victoria Pedretti, Murray Bartlett, Indya Moore. World Premiere. Available online for Public.

A Real Pain / U.S.A., Poland (Director, Screenwriter, and Producer: Jesse Eisenberg, Producers: Dave McCary, Ali Herting, Emma Stone, Jennifer Semler, Ewa Puszczyńska) — Mismatched cousins David and Benji reunite for a tour through Poland to honor their beloved grandmother. The adventure takes a turn when the pair’s old tensions resurface against the backdrop of their family history. Cast: Jesse Eisenberg, Kieran Culkin, Will Sharpe, Jennifer Grey, Kurt Egyiawan. World Premiere. Available online for Public.

Stress Positions / U.S.A. (Director and Screenwriter: Theda Hammel, Producers: Brad Becker-Parton, John Early, Stephanie Roush, Allie Jane Compton, Greg Nobile) — Terry Goon is keeping strict quarantine in his ex-husband’s Brooklyn brownstone while caring for his nephew — a 19-year-old model from Morocco named Bahlul — bedridden in a full leg cast after an electric scooter accident. Unfortunately for Terry, everyone in his life wants to meet the model. Cast: John Early, Qaher Harhash, Theda Hammel, Amy Zimmer, Faheem Ali, John Roberts. World Premiere. Available online for Public.

Suncoast / U.S.A. (Director and Screenwriter: Laura Chinn, Producers: Jeremy Plager, Francesca Silvestri, Kevin Chinoy, Oly Obst) — A teenager who, while caring for her brother along with her audacious mother, strikes up an unlikely friendship with an eccentric activist who is protesting one of the most landmark medical cases of all time. Inspired by a semi-autobiographical story. Cast: Laura Linney, Woody Harrelson, Nico Parker. World Premiere. Available online for Public.

U.S. DOCUMENTARY COMPETITION

As We Speak / U.S.A. (Director and Producer: J.M. Harper, Producers: Sam Widdoes, Peter Cambor, Sam Bisbee) — Bronx rap artist Kemba explores the growing weaponization of rap lyrics in the United States criminal justice system and abroad — revealing how law enforcement has quietly used artistic creation as evidence in criminal cases for decades. World Premiere. Available online for Public.

Daughters / U.S.A. (Directors: Angela Patton, Natalie Rae, Producers: Lisa Mazzotta, Justin Benoliel, Mindy Goldberg, Sam Bisbee, Kathryn Everett, Laura Choi Raycroft) — Four young girls prepare for a special Daddy Daughter Dance with their incarcerated fathers, as part of a unique fatherhood program in a Washington, D.C., jail. World Premiere. Available online for Public.

EVERY LITTLE THING / Australia (Director: Sally Aitken, Producers: Bettina Dalton, Oli Harbottle, Anna Godas) — Amid the glamour of Hollywood, Los Angeles, a woman finds herself on a transformative journey as she nurtures wounded hummingbirds, unraveling a visually captivating and magical tale of love, fragility, healing, and the delicate beauty in tiny acts of greatness. World Premiere. Available online for Public.

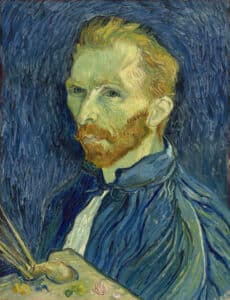

FRIDA / U.S.A., Mexico (Director: Carla Gutiérrez, Producers: Katia Maguire, Sara Bernstein, Justin Wilkes, Loren Hammonds, Alexandra Johnes) — An intimately raw and magical journey through the life, mind, and heart of iconic artist Frida Kahlo. Told through her own words for the very first time — drawn from her diary, revealing letters, essays, and print interviews — and brought vividly to life by lyrical animation inspired by her unforgettable artwork. World Premiere. Available online for Public.

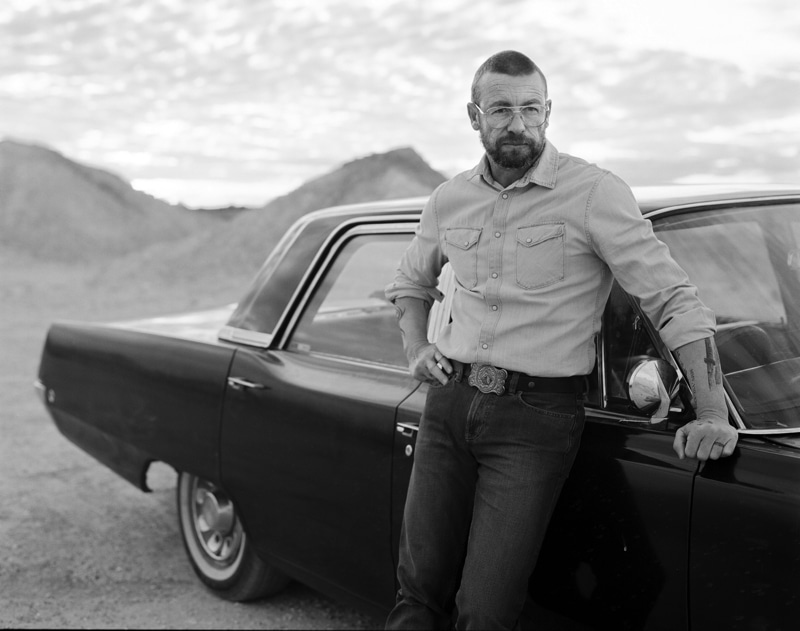

Gaucho Gaucho / U.S.A., Argentina (Directors and Producers: Michael Dweck, Gregory Kershaw, Producers: Cameron O’Reilly, Christos V. Konstantakopoulos, Matthew Perniciaro) — A celebration of a community of Argentine cowboys and cowgirls, known as Gauchos, living beyond the boundaries of the modern world. World Premiere. Available online for Public.

Love Machina / U.S.A. (Director and Producer: Peter Sillen, Producer: Brendan Doyle) — Futurists Martine and Bina Rothblatt commission an advanced humanoid AI named Bina48 to transfer Bina’s consciousness from a human to a robot in an attempt to continue their once-in-a-galaxy love affair for the rest of time. World Premiere. Available online for Public.

Porcelain War / U.S.A., Ukraine (Director and Screenwriter: Brendan Bellomo, Director: Slava Leontyev, Producers and Screenwriters: Aniela Sidorska, Paula DuPre’ Pesmen, Producers: Camilla Mazzaferro, Olivia Ahnemann) — Under roaring fighter jets and missile strikes, Ukrainian artists Slava, Anya, and Andrey choose to stay behind and fight, contending with the soldiers they have become. Defiantly finding beauty amid destruction, they show that although it’s easy to make people afraid, it’s hard to destroy their passion for living. World Premiere. Available online for Public.

Skywalkers: A Love Story / U.S.A. (Director, Screenwriter, and Producer: Jeff Zimbalist, Producers: Maria Bukhonina, Tamir Ardon, Chris Smith, Nick Spicer) — To save their career and relationship, a daredevil couple journey across the globe to climb the world’s last super skyscraper and perform a bold acrobatic stunt on the spire. World Premiere. Available online for Public.

Sugarcane / U.S.A., Canada (Director: Julian Brave NoiseCat, Director and Producer: Emily Kassie, Producer: Kellen Quinn) — An investigation into abuse and missing children at an Indian residential school ignites a reckoning on the nearby Sugarcane Reserve. World Premiere. Available online for Public.

Union / U.S.A. (Directors: Stephen Maing, Brett Story, Producers: Samantha Curley, Mars Verrone) — The Amazon Labor Union (ALU) — a group of current and former Amazon workers in New York City’s Staten Island — takes on one of the world’s largest and most powerful companies in the fight to unionize. World Premiere. Available online for Public.

WORLD CINEMA DRAMATIC COMPETITION

Brief History of a Family / China, France, Denmark, Qatar (Director and Screenwriter: Jianjie Lin, Producers: Ying Lou, Yue Zheng, Yiwen Wang) — A middle-class family’s fate becomes intertwined with their only son’s enigmatic new friend in post one-child policy China, putting unspoken secrets, unmet expectations, and untended emotions under the microscope. Cast: Feng Zu, Keyu Guo, Xilun Sun, Muran Lin. World Premiere. Available online for Public.

Girls Will Be Girls / India, France, Norway (Director, Screenwriter, and Producer: Shuchi Talati, Producers: Richa Chadha, Claire Chassagne) — In a strict boarding school nestled in the Himalayas, 16-year-old Mira discovers desire and romance. But her sexual, rebellious awakening is disrupted by her mother who never got to come of age herself. Cast: Preeti Panigrahi, Kani Kusruti, Kesav Binoy Kiron. World Premiere. Available online for Public.

Handling the Undead / Norway (Director and Screenwriter: Thea Hvistendahl, Screenwriter: John Ajvide Lindqvist, Producers: Kristin Emblem, Guri Neby) — On a hot summer day in Oslo, the newly dead awaken. Three families faced with loss try to figure out what this resurrection means and if their loved ones really are back. Based on the book by John Ajvide Lindqvist. Cast: Renate Reinsve, Bjørn Sundquist, Bente Børsum, Anders Danielsen Lie, Bahar Pars. World Premiere. Available online for Public.

In The Land of Brothers / Iran, France, Netherlands (Directors, Screenwriters, and Producers: Raha Amirfazli, Alireza Ghasemi, Producers: Adrien Barrouillet, Frank Hoeve, Charles Meresse, Emma Binet, Arya Ghamavian) — Three members of an extended Afghan family start their lives over in Iran as refugees, unaware they face a decades-long struggle ahead to be “at home.” Cast: Hamideh Jafari, Bashir Nikzad, Mohammad Hosseini. World Premiere. Available online for Public.

Layla / U.K. (Director and Screenwriter: Amrou Al-Kadhi, Producer: Savannah James-Bayly) — When Layla, a struggling Arab drag queen, falls in love for the first time, they lose and find themself in a transformative relationship that tests who they really are. Cast: Bilal Hasna, Louis Greatorex, Safiyya Ingar, Darkwah, Terique Jarrett, Sarah Agha. World Premiere. Available online for Public.

Malu / Brazil (Director and Screenwriter: Pedro Freire, Producers: Tatiana Leite, Sabrina Garcia, Leo Ribeiro, Roberto Berliner) — Malu — a mercurial, unemployed actress living with her conservative mother in a precarious house in a Rio de Janeiro slum — tries to deal with her strained relationship with her own adult daughter while surviving on memories of her glorious artistic past. Cast: Yara de Novaes, Carol Duarte, Juliana Carneiro da Cunha, Átila Bee. World Premiere. Available online for Public.

Reinas / Switzerland, Peru, Spain (Director and Screenwriter: Klaudia Reynicke, Screenwriter and Producer: Diego Vega, Producers: Britta Rindelaub, Thomas Reichlin, Daniel Vega, Valérie Delpierre) — Surrounded by social and political chaos in Lima during the summer of 1992, Lucia, Aurora, and their mother, Elena, plan to leave and seek opportunities in the United States. Their farewell involves reconnecting with their estranged father, Carlos, adding turbulence to the regrets, hopes, and fears of their emotional departure. Cast: Abril Gjurinovic, Luana Vega, Jimena Lindo, Gonzalo Molina, Susi Sánchez. World Premiere. Available online for Public.

Sebastian / U.K., Finland, Belgium (Director and Screenwriter: Mikko Mäkelä, Producer: James Watson) — Max, a 25-year-old aspiring writer living in London, begins a double life as a sex worker in order to research his debut novel. Cast: Ruaridh Mollica, Hiftu Quasem, Ingvar Sigurdsson, Jonathan Hyde, Leanne Best, Lara Rossi. World Premiere. Available online for Public.

Sujo / Mexico, U.S.A., France (Directors, Screenwriters, and Producers: Astrid Rondero, Fernanda Valadez, Producers: Diana Arcega, Jewerl Keats Ross, Virginie Devesa, Jean-Baptiste Bailly-Maitre) — When a cartel gunman is killed, he leaves behind Sujo, his beloved 4-year-old son. The shadow of violence surrounds Sujo during each stage of his life in the isolated Mexican countryside. As he grows into a man, Sujo finds that fulfilling his father’s destiny may be inescapable. Cast: Juan Jesús Varela, Yadira Pérez, Alexis Varela, Sandra Lorenzano, Jairo Hernández, Kevin Aguilar. World Premiere. Available online for Public.

Veni Vidi Vici / Austria (Director and Screenwriter: Daniel Hoesl, Producer: Ulrich Seidl) — The Maynards and their children lead an almost perfect billionaire family life. Amon is a passionate hunter, but doesn’t shoot animals, as the family’s wealth allows them to live totally free from consequences. Cast: Laurence Rupp, Ursina Lardi, Olivia Goschler. World Premiere. Available online for Public.

WORLD CINEMA DOCUMENTARY COMPETITION

Agent of Happiness / Bhutan, Hungary (Director and Producer: Arun Bhattarai, Director: Dorottya Zurbó, Producers: Noémi Veronika Szakonyi, Máté Artur Vincze) — Amber is one of the many agents working for the Bhutanese government to measure people’s happiness levels among the remote Himalayan mountains. But will he find his own along the way? World Premiere. Available online for Public.

The Battle for Laikipia / Kenya, U.S.A. (Director and Producer: Daphne Matziaraki, Director: Peter Murimi, Producer: Toni Kamau) — Unresolved historical injustices and climate change raise the stakes in a generations-old conflict between Indigenous pastoralists and white landowners in Laikipia, Kenya, a wildlife conservation haven. World Premiere. Available online for Public.

Black Box Diaries / Japan, U.S.A., U.K. (Director and Producer: Shiori Ito, Producers: Eric Nyari, Hanna Aqvilin) — Journalist Shiori Ito embarks on a courageous investigation of her own sexual assault in an improbable attempt to prosecute her high-profile offender. Her quest becomes a landmark case in Japan, exposing the country’s outdated judicial and societal systems. World Premiere. Available online for Public.

Eternal You / Germany, U.S.A. (Directors: Hans Block, Moritz Riesewieck, Producers: Christian Beetz, Georg Tschurtschenthaler) — Startups are using AI to create avatars that allow relatives to talk with their loved ones after they have died. An exploration of a profound human desire and the consequences of turning the dream of immortality into a product. World Premiere. Available online for Public.

Ibelin / Norway (Director: Benjamin Ree, Producer: Ingvil Giske) — Mats Steen, a Norwegian gamer, died of a degenerative muscular disease at the age of 25. His parents mourned what they thought had been a lonely and isolated life, when they started receiving messages from online friends around the world. World Premiere. Available online for Public.

IGUALADA / Colombia, U.S.A., Mexico (Director: Juan Mejía Botero, Producers: Juan E. Yepes, Daniela Alatorre, Sonia Serna) — In one of Latin America’s most unequal countries, Francia Márquez, a Black Colombian rural activist, challenges the status quo with a presidential campaign that reappropriates the derogatory term “Igualada” — someone who acts as if they deserve rights that supposedly don’t correspond to them — and inspires a nation to dream. World Premiere. Available online for Public.

Never Look Away / New Zealand (Director, Screenwriter, and Producer: Lucy Lawless, Screenwriters and Producers: Matthew Metcalfe, Tom Blackwell) — New Zealand–born groundbreaking CNN camerawoman Margaret Moth risks it all to show the reality of war from inside the conflict, staring down danger and confronting those who perpetuate it. World Premiere. Available online for Public.

A still from A New Kind of Wilderness by Silje Evensmo Jacobsen, an official selection of the World Documentary Competition at the 2024 Sundance Film Festival. Courtesy of Sundance Institute. Photo by Maria Gros Vatne.

A New Kind of Wilderness / Norway (Director: Silje Evensmo Jacobsen, Producer: Mari Bakke Riise) — In a forest in Norway, a family lives an isolated lifestyle in an attempt to be wild and free, but a tragic event changes everything, and they are forced to adjust to modern society. World Premiere. Available online for Public.

Nocturnes / India, U.S.A. (Director and Producer: Anirban Dutta, Director: Anupama Srinivasan) — In the dense forests of the Eastern Himalayas, moths are whispering something to us. In the dark of night, two curious observers shine a light on this secret universe. World Premiere. Available online for Public.

Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat / Belgium, France, Netherlands (Director and Screenwriter: Johan Grimonprez, Producers: Daan Milius, Rémi Grellety) — In 1960, United Nations: the Global South ignites a political earthquake, musicians Abbey Lincoln and Max Roach crash the Security Council, Nikita Khrushchev bangs his shoe denouncing America’s color bar, while the U.S. dispatches jazz ambassador Louis Armstrong to the Congo to deflect attention from its first African post-colonial coup. World Premiere. Available online for Public.

NEXT

Desire Lines / U.S.A. (Director, Screenwriter, and Producer: Jules Rosskam, Screenwriter: Nate Gualtieri, Producers: André Pérez, Amy E. Powell, Brittani Ward) — Past and present collide when an Iranian American trans man time-travels through an LGBTQ+ archive on a dizzying and erotic quest to unravel his own sexual desires. Cast: Theo Germaine, Aden Hakimi. World Premiere. Documentary. Available online for Public.

Kneecap / Ireland, U.K. (Director and Screenwriter: Rich Peppiatt, Producers: Jack Tarling, Trevor Birney) — There are 80,000 native Irish speakers in Ireland. 6,000 live in the North of Ireland. Three of them became a rap group called Kneecap. This anarchic Belfast trio becomes the unlikely figurehead of a civil rights movement to save the mother tongue. Cast: Liam Óg Ó hAnnaidh, Naoise Ó Cairealláin, JJ Ó Dochartaigh, Michael Fassbender, Josie Walker, Simone Kirby). World Premiere. Fiction. Available online for Public.

Little Death / U.S.A. (Director and Screenwriter: Jack Begert, Screenwriter: Dani Goffstein, Producers: Darren Aronofsky, Andy S. Cohen, Dylan Golden, Brendan Naylor, Sam Canter, Noor Alfallah) — A middle-aged filmmaker on the verge of a breakthrough. Two kids in search of a lost backpack. A small dog a long way from home. Cast: David Schwimmer, Gaby Hoffmann, Dominic Fike, Talia Ryder, Jena Malone, Sante Bentivoglio. World Premiere. Fiction. Available online for Public.

REALM OF SATAN / U.S.A. (Director and Screenwriter: Scott Cummings, Producers: Caitlin Mae Burke, Pacho Velez, Molly Gandour) — An experiential portrait depicting Satanists in both the everyday and in the extraordinary as they fight to preserve their lifestyle: magic, mystery, and misanthropy. Cast: Peter Gilmore, Peggy Nadramia, Blanche Barton. World Premiere. Documentary. Available online for Public.

Seeking Mavis Beacon / U.S.A. (Director and Writer: Jazmin Renée Jones, Producer: Guetty Felin)— Launched in the late ’80s, educational software Mavis Beacon Teaches Typing taught millions globally, but the program’s Haitian-born cover model vanished decades ago. Two DIY investigators search for the unsung cultural icon, while questioning notions of digital security, AI, and Black representation in the digital realm. World Premiere. Documentary. Available online for Public.

Tendaberry / U.S.A. (Director, Screenwriter, and Producer: Haley Elizabeth Anderson, Producers: Carlos Zozaya, Matthew Petock, Zachary Shedd, Hannah Dweck, Theodore Schaefer, Daniel Patrick Carbone) — When her boyfriend goes back to Ukraine to be with his ailing father, 23-year-old Dakota anxiously navigates her precarious new reality, surviving on her own in New York City. Cast: Kota Johan, Yuri Pleskun. World Premiere. Fiction. Available online for Public.

PREMIERES

The American Society of Magical Negroes / U.S.A. (Director, Screenwriter, and Producer: Kobi Libii, Producers: Julia Lebedev, Eddie Vaisman, Angel Lopez) — A young man, Aren, is recruited into a secret society of magical Black people who dedicate their lives to a cause of utmost importance: making white people’s lives easier. Cast: Justice Smith, David Alan Grier, An-Li Bogan, Drew Tarver, Rupert Friend, Nicole Byer. World Premiere. Fiction.

And So It Begins / U.S.A., Philippines (Director, Screenwriter, and Producer: Ramona S. Diaz) — Amidst the traditional pomp and circumstance of Filipino elections, a quirky people’s movement rises to defend the nation against deepening threats to truth and democracy. In a collective act of joy as a form of resistance, hope flickers against the backdrop of increasing autocracy. World Premiere. Documentary. Available online for Public.

DEVO / U.K., U.S.A. (Director: Chris Smith, Producers: Chris Holmes, Anita Greenspan, Danny Gabai) — Born in response to the Kent State massacre, new wave band Devo took their concept of “de-evolution” from cult following to near–rock star status with groundbreaking 1980 hit “Whip It” while preaching an urgent social commentary. World Premiere. Documentary.

A Different Man / U.S.A. (Director and Writer: Aaron Schimberg, Producers: Christine Vachon, Vanessa McDonnell, Gabriel Mayers) — Aspiring actor Edward undergoes a radical medical procedure to drastically transform his appearance. But his new dream face quickly turns into a nightmare, as he loses out on the role he was born to play and becomes obsessed with reclaiming what was lost. Cast: Sebastian Stan, Renate Reinsve, Adam Pearson. World Premiere. Fiction.

Freaky Tales / U.S.A. (Directors, Screenwriters, and Producers: Ryan Fleck, Anna Boden, Producers: Poppy Hanks, Jelani Johnson) — In 1987 Oakland, a mysterious force guides The Town’s underdogs in four interconnected tales: Teen punks defend their turf against Nazi skinheads, a rap duo battles for hip-hop immortality, a weary henchman gets a shot at redemption, and an NBA All-Star settles the score. Basically another day in the Bay. Cast: Pedro Pascal, Jay Ellis, Normani Kordei Hamilton, Dominique Thorne, Ben Mendelsohn, Ji-Young Yoo. World Premiere. Fiction.

Ghostlight / U.S.A. (Director and Screenwriter: Kelly O’Sullivan, Director and Producer: Alex Thompson, Producers: Pierce Cravens, Chelsea Krant, Ian Keiser, Eddie Linker, Alex Wilson) — When a construction worker unexpectedly joins a local theater’s production of Romeo and Juliet, the drama onstage starts to mirror his own life. Cast: Keith Kupferer, Dolly de Leon, Katherine Mallen Kupferer, Tara Mallen. World Premiere. Fiction.

SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL | 18 – 28 JANUARY 2024

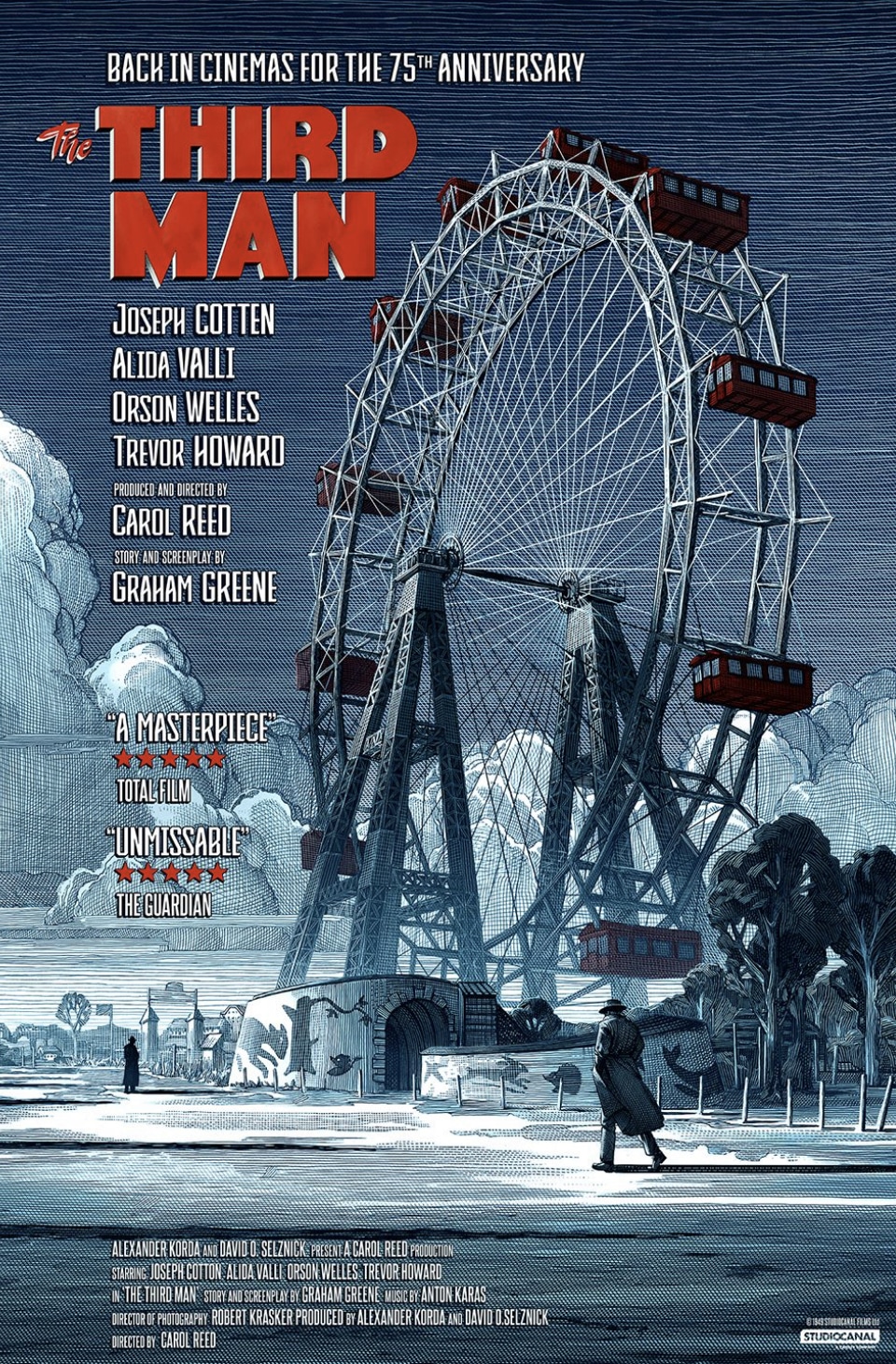

IFFR FROM 30 JANUARY UNTIL 9 FEBRUARY 2025 | featuringTHE TIGER, BIG SCREEN AND TIGER SHORTS COMPETITIONS

IFFR FROM 30 JANUARY UNTIL 9 FEBRUARY 2025 | featuringTHE TIGER, BIG SCREEN AND TIGER SHORTS COMPETITIONS

Dir: Cristobal Leon, Joaquin Cocina | Drama, Chile 64′

Dir: Cristobal Leon, Joaquin Cocina | Drama, Chile 64′

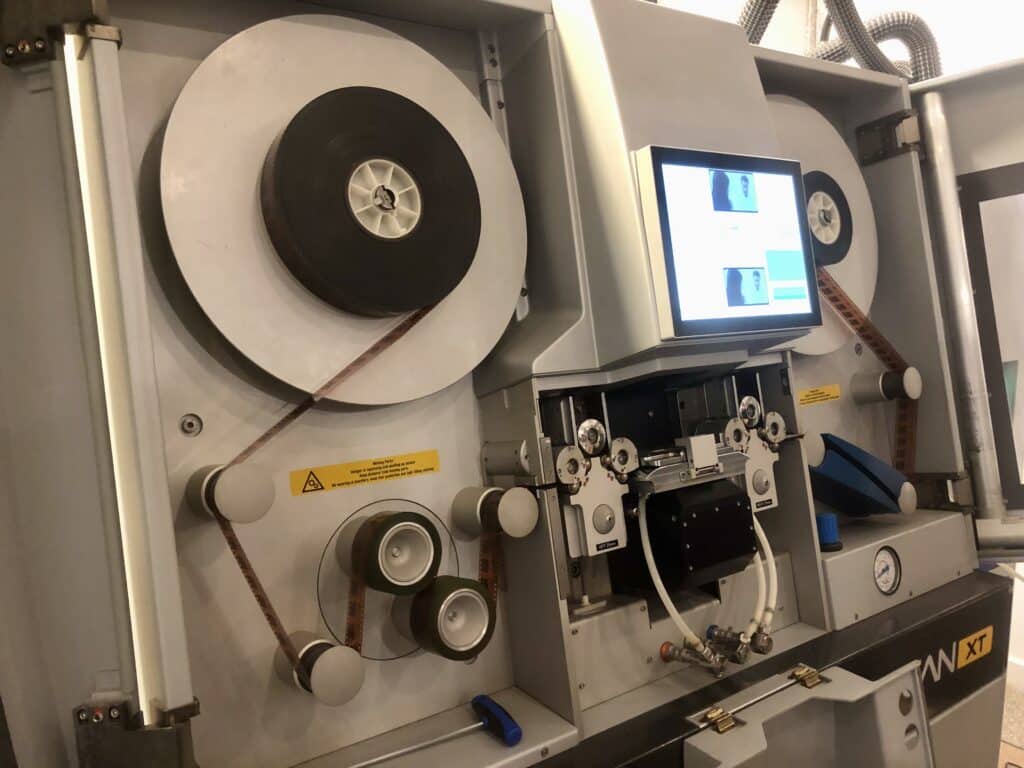

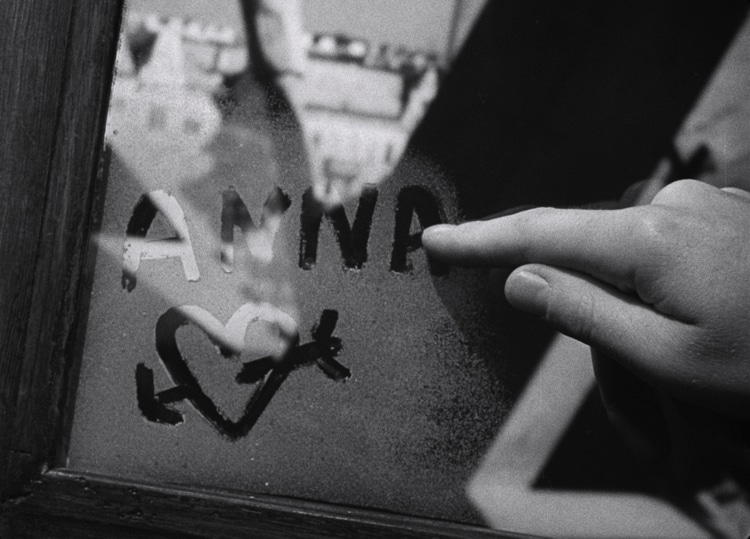

Bergamo Film Meeting unveils its 42nd edition from March 9 – 17, 2024. One of the most important events in the Italian festival calendar the meeting draws thousands to its annual celebration of auteur and arthouse cinema in the mountainside venue just north of Milan in the Italian Dolomites.

Bergamo Film Meeting unveils its 42nd edition from March 9 – 17, 2024. One of the most important events in the Italian festival calendar the meeting draws thousands to its annual celebration of auteur and arthouse cinema in the mountainside venue just north of Milan in the Italian Dolomites.