Susanne Bier and Christopher Kyle were at the London Film Festival with their new film arthouse drama SERENA which stars Bradley Cooper and Jennifer Lawrence. Matthew Turner spoke to them:

How did the project come about, first of all?

Christopher Kyle (CK): I read this remarkable novel when it was still in galleys and I really asked my agent to go after it hard and eventually got the job to adapt it. I was really attracted to the dark love story, to see a woman in this crazy macho world of the logging camp, the way they love nature and want to destroy it at the same time, all these big themes were really exciting as a writer to dig into, so I started working on the script, wrote a draft and then a year later, Susanne got involved and we started working on it together.

Susanne, what was the appeal of the project for you?

Susanne Bier (SB): The same. (Laughs). No, I mean, I was attracted by the dark love story and I was attracted by the fact of having this woman who is forceful and who is actually more capable than most of the men and who has a kind of a damaged soul, in a way. I was very attracted by all of those elements. And I still am.

With regards to getting on board with the project, is it right that Darren Aronofsky and Angelina Jolie were originally tied to the project and was there trepidation for you to pick it up after that?

CK: You know, the nature of this business is that people get attached to projects and then unattached to projects – it happens all the time. Darren was involved with the project for six or eight months and then financing came through for Black Swan, so he became unavailable, so we moved on. He did talk to Angelina at one point, I don’t know how far that got, but that’s normal, you talk to actors, you see who’s interested. None of that developed very far before Susanne got involved.

What had you seen Jennifer Lawrence in at the time that she was cast in Serena?

SB: Winter’s Bone. And that’s it. She had not yet done Hunger Games and she had not worked with Bradley. So she got involved and, actually, at the time, she had only done Winter’s Bone and because she was a clearly very talented, very beautiful, very interesting young actress, but not yet a big star, it was quite difficult financing the movie on the basis of her, so it took a little while. But on our first conversation – I mean, she now claims that it was her idea [to cast] Bradley, but I was also going to talk to her about Bradley, so it was clearly both of us who had the same idea, and then we asked Bradley and he was quite keen to get involved and he was quite keen to portray a kind of slightly troublesome character, someone who is an idealist, but an idealist for reasons that today we don’t really consider particularly proper or particularly wholesome. And I was very fortunate that both of them wanted to be attached, but then it took longer to finance it. And in the interim, Jennifer had then done Hunger Games and they then did Silver Linings, but none of the movies had come out when we shot Serena.

What had Bradley Cooper done when he was cast then? Had he done Limitless?

SB: He’d done Limitless, he’d done The Hangover, he was an established star, which is sort of what made it possible to finance it. And then she became a huge big star in the interim.

You also have so many great British actors in the cast – I’m thinking of Sean Harris, Rhys Ifans, Toby Jones and so on. How did they get involved?

SB: There are Danish stars too! The movie was shot in Prague. It was tempting to partly use a European cast, but also I always felt that Britain has this richness of amazing character actors, character actors who are really distinct and special. And so the script was full of archetypes, like the archetype sheriff and the archetype villain, in a way. And actually, we were pretty much agreed that it would be really interesting having character actors who would not just fit into the archetype and would add something very extra to the characters. So, Rhys Ifans, who has a very gentle way of talking, that just makes him doubly scary when he plays the villain.

Did you have many of those character actors in mind early on in the process then, when you were looking at the script?

SB: It came together quite quickly. Once we started casting out of Britain, it was very joyful and fun to do that, because it left space for slightly unexpected choices.

How was the experience of working together?

SB: Very problematic. (Laughs).

CK: Susanne’s like a dream for a screenwriter. I mean, she knows what she wants, she can be very clear about what she needs from the script, but she’s also a great collaborator, she listens, she’s willing to entertain other ideas, so you really can’t ask for anything more, as a writer.

SB: That’s very nice of you! I want to say the same thing. But we have a tone between us where the characteristic of the tone is that we don’t pay each other compliments!

CK: We express our fondness through insults, which is unusual.

That’s very British…

SB: Which is quite fun! We’re actually having a lot of fun, I want to say. And it’s actually been really seamless and very creative.

CK: I wish it was always like this!

You mentioned Danish actors. I spotted Kim Bodnia on screen for maybe two or three seconds. So does that mean that you cut quite a lot out that you were sorry to see go?

SB: Yes. I think what happened in the process of the script was – it’s such rich material and the novel was such rich material that the challenge is losing scenes you love. The challenge is not losing things you don’t like, because that’s easy to do. The challenge is losing things you love. And that was true for the script as well as for the editing. And there was possibly a bit too much complexity in the film in the first edit, which is why we actually had to focus on the love story, which is why certain characters became much less prevalent or almost virtually disappeared. So Kim Bodnia was Rachel’s father in the film and he was one of those characters.

Susanne, you tend to explore relationships in your films rather than creating something effects-driven or, say, an action film. Do you find that this is something that you particularly connect with and interests you still?

SB: I am interested in human beings. I am interested in relationships. Basically, that’s the only thing that interests me. However much I theoretically would love to do a real action film, I can’t really see myself engaging for hours and hours about a car chase. The thing is that I really enjoy some of them. I enjoy the ones that still have a human aspect to them or the ones that have a sense of humour, but I am always longing for the car chase to stop and for them to start talking, or kissing, or any other possible human exchanges.

CK: Certain types of movies get so technical that the director spends all their doing everything but work with the actors on the human beings in the story.

SB: It would drive me crazy and I can’t really see anyone who would offer me that type of movie!

You have two films at this festival, Serena and A Second Chance. Will you continue to go back and forth between Hollywood and making films in Europe?

SB: I would love to, but it’s also a little bit about working in different financial scales and that’s probably the major difference.

What are the main pros and cons of both?

SB: The pros (of working in Hollywood) are that you can actually make an epic picture, which is really attractive and satisfying in terms of beauty and the whole cinematic experience. The cons are that it is a more complicated process.

So, is it a case that the reverse is true, where making films in Europe is a more streamlined and simple process but the financing is harder?

SB: Ah, but then when you see a lot of small European films, you wish it were a more complicated process, because there is also that thing of an auteur arrogance in Europe. ‘I’m the director, nobody’s going to say anything, so I’m just going to do the movie I want to make’. Then it’s a three-hour long, incomprehensible and very boring movie. I do actually think there is a kind of healthiness in a bit of an exchange. I don’t think making a movie by committee works either, but I think that a certain relevant questioning is probably healthy.

In the first half of the film we see the start of the relationship between the two central characters. In a lot of the scenes where they are alone together, it just becomes a sex scene. Was that a conscious decision?

SB: Love is a funny thing. I think that we wanted to suggest the character of their love was also a very physical character. I do also think that the trigger for someone like Serena, to make her so crazy, is also a physical love. You’re right, but that was also in the nature of the love affair. Yes, of course, you could have made another sort of love affair, but we didn’t want to do that.

We’re experiencing a strong time for television and, in particular, Scandinavian television. Would either of you ever be tempted to move into that?

SB: For me, television is the most exciting thing. It’s the most exciting place to be right now so, yes, absolutely. I think one has to live in the last century for not recognising where most, but not all, of the… well, it’s also where the best writing is. [Turns to Kyle] Don’t you agree?

CK: It’s so depressing trying to get work as a screenwriter in Hollywood right now, because all the movies are about toys or comic books. Opportunities like Serena are extremely rare and very competitive, because all the writers want those jobs, so where there’s growth, where there’s excitement, is television. Not just in the US, but all over the world. Everybody’s clamouring for these interesting, serious dramas with good writing, good acting and good directing. The production values have exploded. You see something like True Detective. It’s shot like a beautiful eight hour movie, which wasn’t what television was like 5 or 10 years ago at all. A lot of people are excited about television…

SB: I also like watching it! And I want to say, particularly, in writing. You mentioned Scandinavia, because I actually think that the writing in Scandinavian films is still, comparatively, really good, but I think that particularly in America, I think that the writing in television is way better than the writing in films.

Does that mean that it is just a question of you waiting for the right project to come along? Or would you be thinking about producing or developing your own material?

SB: I’d love to do television. Whether it would be me initiating it or doing a project with him [indicates Kyle], I would be very intrigued by that.

CK: I’ve just made a deal to write a pilot for FX, based on a French historical novel called ‘The Cursed King’, it’s about the 14th century and the events that led to the 100 years’ war.

What was the hardest thing to get right in Serena?

SB: The hardest thing was balancing the fact that we’re dealing with two fraught human beings and still rooting for them, because it’s all very well having a clean heroine or a clean hero, but the complexity of what the characters are doing, and yet still being attracted to them; still being fascinated by them; not being repulsed by them. I think that’s probably the trickiest balance of all.

CK: I agree; the tone. It’s very tricky when you place at the centre of a film characters who do things that are objectively offensive. And yet, if you make them compelling, fascinating and complex enough, the audience will go with them. Last night, a young woman at the Q&A was going all the way with Serena to the point where she said she was rooting against Rachel and the baby.

Was something like Macbeth at the forefront in terms of references?

CK: Yes, absolutely, and that starts with the novel. The novelist was inspired by Lady Macbeth and also Medea; these tragedies with strong women at the centre of them, so that was something we were conscious of from the beginning.

Were there any other specific reference points for you when making the film?

SB: There were a number of references. There was a noir reference. A Barbara Stanwyck, noir reference. It was very important for me to give this a contemporary feel, but that there was also a sense of psychology; that she wasn’t just an evil black widow that would just seduce a man, because I don’t feel that a contemporary female audience would respond to that. I feel that a contemporary female audience would respond to someone who might behave in an offensive way, but we still understand her, which is what I was trying to aim at.

Was that perhaps the biggest tussle that you might have had with the original source material, in terms of making sure you walk that delicate tightrope, right between not alienating the audience from the actions these characters are taking, making them sympathetic enough that they can still go with it, was that a challenge?

SB: Yes, a big challenge.

CK: It’s always a challenge with a novel, because novels can tell you what a character’s thinking, but in a film you only get to see what they do and what they say, so it can be more challenging to get that nuance sometimes.

In relation to the locations that you chose, because it’s set in Carolina, but you shot in Prague. Obviously with these Hollywood film stars – well, they weren’t both stars then, but Bradley Cooper was – you had to bring them over. Was it a convenience for you to be in Europe rather than in America?

SB: Because it was way more financially viable. And so it made sense. I mean, one of the things you want to do as a filmmaker is that you want to have the most part of it on screen, so you’ll go to great lengths to secure that. And, as we spoke about, since you don’t automatically just inflate the budget, that would be one of the decisions.

I have to ask a slightly facetious question: what do you have against babies? You have terrible, terrible things happening in A Second Chance…

SB: Stop saying that! I don’t want you to say that! Firstly, here’s the thing: I love babies. I mean, I’m crazy about babies. I’m kind of dangerous, to be honest. And so the truth is that it would be more tempting for me to steal babies than anything else.

So it’s a coincidence that it’s been terrible things happening to babies back to back?

SB: The babies on set had a great time.

CK: All of her children lived to adulthood. She took good care of them.

What’s your next project?

SB: Probably Mary Queen of Scots, with Working Title.

I wanted to ask about your other film in the festival, A Second Chance. How did A Second Chance come about?

SB: Well, it was the result of a collaboration between myself and my other writer, Anders Thomas Jensen, he wrote it. And he’s had four kids in a very brief period of time, so maybe you should ask him about what he thinks of babies.

And the casting for that? How did you get those two involved?

SB: Are you talking about Nicolaj Coster-Waldau? I asked him. He’s, you know, he’s Danish, and I know he comes out, and you know him from Game of Thrones, and we all know that he doesn’t really have a hand. But I’ve been looking, he hasn’t done a Danish film for 10 years or something, and I’ve kind of been looking to find a movie to work with him in. And when we had the first draft of this one, I thought, ‘He’s going to be amazing in it.’

I think Nicolaj Lie Kaas is a really fascinating actor, because he can play heroes and he can play villains, there’s not really very many people who can do both so brilliantly.

SB: It’s crazy, he’s crazily good at both. He’s really amazing.

So was getting him involved an important part of the film? Also, those two actors together, you don’t often see two such big Danish actors together in the same film these days, so was it important to have those two big presences together?

SB: Yes, and also Nicolaj Lie Kaas is probably the most funny person on the planet, so he just needs to be on set so I can laugh.

CK: That’s your number one, yeah?

SB: Do you think I’m getting silly? Do you think I’m being very un-serious there? Because I can feel it, the seriousness slipping out.

In relation to these two films, was there any overlap at all, or has Serena basically sat in the can for a bit longer?

SB: No, there was overlap, that was part of the delay of Serena. We had a delay in editing, and then we realised that the ADR was gonna be a real challenge, because it was shot in Prague, and it was huge on the ADR. And then I had another film, that I was committed to doing, so there was, I did that one while doing post on Serena, so there was a kind of crazy–

That must be really hard.

SB: I don’t know, it wasn’t necessarily hard, but it was crazy in terms of logistics, and planning and actually finishing Serena. But, I now have two films.

Yeah, exactly, that’s true. Do you have a favourite?

SB: That’s exactly what my kids ask me, and I consistently say, you know, when my son asks me I say, ‘Of course I love my daughter much more than I love you.’

Going back to the question of adaptation, I haven’t actually read the book but it’s my understanding that the endings of the book (of Serena) and the film are quite different. What was it that made you want to make the large changes to that in particular?

CK: You know when you adapt a book it ends up taking on its own logic. You start with what you see as the core story of the book, which was this love story, between these two really dark and interesting characters, and then start stripping away and trying to focus on the best parts of that story for the film. And then you have to look at it as the story that you have in the screenplay, and how do you end that story, regardless of how the book, which is tying together all these other plotlines that you’re not really using. So it’s just a process that you get to, and this ending seemed to make the most sense for the story we were telling.

SB: It’s also that sometimes in a movie, making a very long time gap gets complicated. And I think we kind of felt that it suited this move to actually finish within its own world.

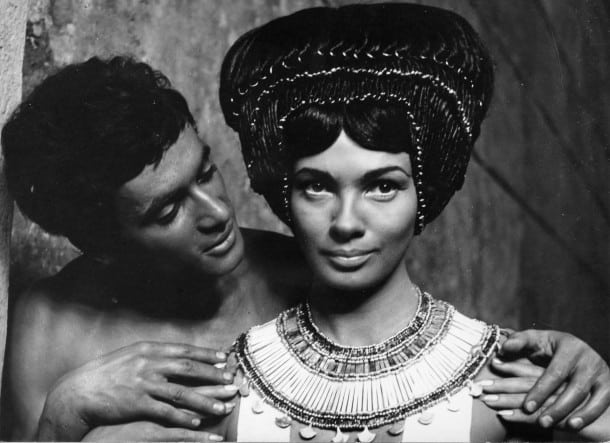

Karina went on to star in seven of his films, the first was Le Petit Soldat that same year. She won Best Actress at the Berlin Film Festival in 1961 for Une Femme est une Femme. While marriage to Godard was stormy to say the least – he neglected her emotionally – “he was the sort of man who would go for a packet of cigarettes and return three weeks later” – their artistic relationship blossomed with a string of New Wave hits: Vivre sa Vie (1962); Bande a Part (1964); Pierrot Le Fou (1965); Alphaville (1965) and Made in USA (1966). When Godard cast her in his episode ‘Anticipation’ for The Oldest Profession (1966), they were already divorced and not on speaking terms. But Karina stayed loyal to Godard and a few years ago at the BFI she talked about him in glowing terms.

Karina went on to star in seven of his films, the first was Le Petit Soldat that same year. She won Best Actress at the Berlin Film Festival in 1961 for Une Femme est une Femme. While marriage to Godard was stormy to say the least – he neglected her emotionally – “he was the sort of man who would go for a packet of cigarettes and return three weeks later” – their artistic relationship blossomed with a string of New Wave hits: Vivre sa Vie (1962); Bande a Part (1964); Pierrot Le Fou (1965); Alphaville (1965) and Made in USA (1966). When Godard cast her in his episode ‘Anticipation’ for The Oldest Profession (1966), they were already divorced and not on speaking terms. But Karina stayed loyal to Godard and a few years ago at the BFI she talked about him in glowing terms.

Dir: Karyn Kusama | Wri: Phil Hay | US Thriller 100′

Dir: Karyn Kusama | Wri: Phil Hay | US Thriller 100′ Joanna Hogg is the only living female filmmaker who portrays a particular English contemporary milieu. Usually creative, invariably white and well-educated, these characters are liberal in outlook and mostly live in London. With such unique sensibilities and vision she is able to understand and convey as certain type of middle class angst (borne out of having to do the right thing, irrespective of personal choice). She did it gracefully in Unrelated (2007), Archipelago (2010) and Exhibition (2013), And she does it peerlessly again here with The Souvenir, a nuanced and delicately drawn story of addiction and strained relationships that very much echoes its time and place: the late 1980s – although it was inspired and takes its name from Fragonard’s painting, a motif that runs through the film.

Joanna Hogg is the only living female filmmaker who portrays a particular English contemporary milieu. Usually creative, invariably white and well-educated, these characters are liberal in outlook and mostly live in London. With such unique sensibilities and vision she is able to understand and convey as certain type of middle class angst (borne out of having to do the right thing, irrespective of personal choice). She did it gracefully in Unrelated (2007), Archipelago (2010) and Exhibition (2013), And she does it peerlessly again here with The Souvenir, a nuanced and delicately drawn story of addiction and strained relationships that very much echoes its time and place: the late 1980s – although it was inspired and takes its name from Fragonard’s painting, a motif that runs through the film.

MARIE-LOUISE IRIBE Parisian actress and filmmaker, Marie Louise Iribe (1894-1934) had a short but dazzling career and is best known for her 1928 debut Hara-Kiri (co-directed with Henri Debain). Her follow-up Le Roi de Aulnes (1931) is based on a poem by Goethe. This enchanting filigree fairy tale has the same magical touch and look as Cocteau’s La Belle et la Bête which followed 15 years later and during wartime. The simple but moving storyline sees a man riding through hill and dale to carry his injured son home. As he slips in an out of consciousness the boy imagines death as a mythical king surrounded by wood nymphs. Emile Pierre delicately overlays the forest journey with ethereal images of the king in iridescent armour, transformed from a humble toad realised by DoP Emilie Pierre’s ethereal double exposures. Max D’Ollone’s atmospheric score brings the magic to life.

MARIE-LOUISE IRIBE Parisian actress and filmmaker, Marie Louise Iribe (1894-1934) had a short but dazzling career and is best known for her 1928 debut Hara-Kiri (co-directed with Henri Debain). Her follow-up Le Roi de Aulnes (1931) is based on a poem by Goethe. This enchanting filigree fairy tale has the same magical touch and look as Cocteau’s La Belle et la Bête which followed 15 years later and during wartime. The simple but moving storyline sees a man riding through hill and dale to carry his injured son home. As he slips in an out of consciousness the boy imagines death as a mythical king surrounded by wood nymphs. Emile Pierre delicately overlays the forest journey with ethereal images of the king in iridescent armour, transformed from a humble toad realised by DoP Emilie Pierre’s ethereal double exposures. Max D’Ollone’s atmospheric score brings the magic to life. Set in the peaceful charm of the former Bohemia, Karlovy Vary was once known as Marienbad. The annual Film Festival is one of the oldest and most prestigious in the World dating back to 1946. It is backed by the Ministry of Culture and hosted by the Grand Hotel Pupp. But most of the screenings take place in the Brutalist concrete Hotel Thermal which has now become somewhat of an iconic tribute to the country’s years under Communism.

Set in the peaceful charm of the former Bohemia, Karlovy Vary was once known as Marienbad. The annual Film Festival is one of the oldest and most prestigious in the World dating back to 1946. It is backed by the Ministry of Culture and hosted by the Grand Hotel Pupp. But most of the screenings take place in the Brutalist concrete Hotel Thermal which has now become somewhat of an iconic tribute to the country’s years under Communism.  EAST OF THE WEST

EAST OF THE WEST DOCUMENTARY FILMS – COMPETITION

DOCUMENTARY FILMS – COMPETITION Official Selection – Out of Competition

Official Selection – Out of Competition

LATE NIGHT U.S.A. (Director: Nisha Ganatra, Screenwriter: Mindy Kaling) – Legendary late-night talk show host’s world is turned upside down when she hires her only female staff writer. Originally intended to smooth over diversity concerns, her decision has unexpectedly hilarious consequences as the two women separated by culture and generation are united by their love of a biting punchline.

LATE NIGHT U.S.A. (Director: Nisha Ganatra, Screenwriter: Mindy Kaling) – Legendary late-night talk show host’s world is turned upside down when she hires her only female staff writer. Originally intended to smooth over diversity concerns, her decision has unexpectedly hilarious consequences as the two women separated by culture and generation are united by their love of a biting punchline. THE FAREWELL U.S.A., China (Director/Screenwriter: Lulu Wang) – A headstrong Chinese-American woman returns to China when her beloved grandmother is given a terminal diagnosis. Billi struggles with her family’s decision to keep grandma in the dark about her own illness as they all stage an impromptu wedding to see grandma one last time.

THE FAREWELL U.S.A., China (Director/Screenwriter: Lulu Wang) – A headstrong Chinese-American woman returns to China when her beloved grandmother is given a terminal diagnosis. Billi struggles with her family’s decision to keep grandma in the dark about her own illness as they all stage an impromptu wedding to see grandma one last time. CORPORATE ANIMALS U.S.A. (Director: Patrick Brice, Screenwriter: Sam Bain) – Disaster strikes when the egotistical CEO of an edible cutlery company leads her long-suffering staff on a corporate team- building trip in New Mexico. Trapped underground, this mismatched and disgruntled group must pull together to survive. CAST: Demi Moore, Ed Helms, Jessica Williams, Karan Soni

CORPORATE ANIMALS U.S.A. (Director: Patrick Brice, Screenwriter: Sam Bain) – Disaster strikes when the egotistical CEO of an edible cutlery company leads her long-suffering staff on a corporate team- building trip in New Mexico. Trapped underground, this mismatched and disgruntled group must pull together to survive. CAST: Demi Moore, Ed Helms, Jessica Williams, Karan Soni THE BRINK U.S.A. (Director: Alison Klayman) – Now unconstrained by an official White House post, Steve Bannon is free to peddle influence as a perceived kingmaker with a direct line to the President. As self-appointed leader of the “populist movement,” he travels around the U.S. and the world spreading his hard-line anti-immigration message

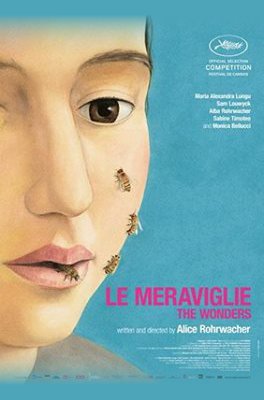

THE BRINK U.S.A. (Director: Alison Klayman) – Now unconstrained by an official White House post, Steve Bannon is free to peddle influence as a perceived kingmaker with a direct line to the President. As self-appointed leader of the “populist movement,” he travels around the U.S. and the world spreading his hard-line anti-immigration message The four Palme d’Or hopefuls directed by women are— Mati Diop’s Atlantique (she was memorable in

The four Palme d’Or hopefuls directed by women are— Mati Diop’s Atlantique (she was memorable in Jury

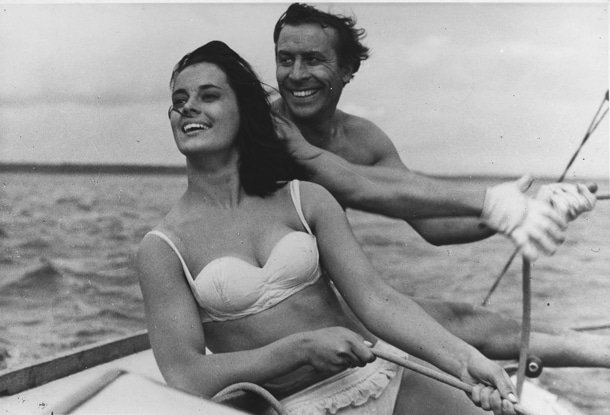

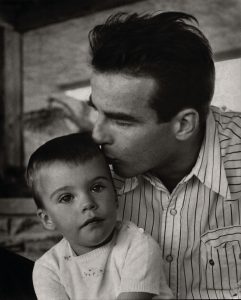

Jury Co-directing and narrating this eye-opening documentary, Robert Clift (who never knew Monty) digs into a treasure trove of family archives and memorabilia (Brooks recorded everything) to reveal an affectionate, fun-loving talent who loved men and dated and lived with women, according to close friends. Monty chose his roles carefully during the ’40s and ’50s, declining to sign a contract to retain complete artistic independence from the studio system with the ability to pick and chose, and re-write his dialogue. This freedom also enabled him to keep much of his private life out of the headlines, although his memory was eventually sullied by tabloid melodrama with his untimely death at only 45. His acting ability and dazzling looks certainly gained him a place in the Hollywood firmament with a select filmography of just 20 features, four of them Oscar-nominated.

Co-directing and narrating this eye-opening documentary, Robert Clift (who never knew Monty) digs into a treasure trove of family archives and memorabilia (Brooks recorded everything) to reveal an affectionate, fun-loving talent who loved men and dated and lived with women, according to close friends. Monty chose his roles carefully during the ’40s and ’50s, declining to sign a contract to retain complete artistic independence from the studio system with the ability to pick and chose, and re-write his dialogue. This freedom also enabled him to keep much of his private life out of the headlines, although his memory was eventually sullied by tabloid melodrama with his untimely death at only 45. His acting ability and dazzling looks certainly gained him a place in the Hollywood firmament with a select filmography of just 20 features, four of them Oscar-nominated. Particularly interesting are Brooks’ conversations with Patricia Bosworth, one of the film’s talking heads and the author of a 1978 biography of Clift that inspired later biographies, but has so far become the accepted version of events, although she apparently got many details wrong and certainly lost out to Jenny Balaban in the Monty relationship stakes, when Barney Balaban (President of Paramount) invited the young actor to join them on a family holiday. He is seen messing around on the beach where he cuts a dash with his good looks and exuberance.

Particularly interesting are Brooks’ conversations with Patricia Bosworth, one of the film’s talking heads and the author of a 1978 biography of Clift that inspired later biographies, but has so far become the accepted version of events, although she apparently got many details wrong and certainly lost out to Jenny Balaban in the Monty relationship stakes, when Barney Balaban (President of Paramount) invited the young actor to join them on a family holiday. He is seen messing around on the beach where he cuts a dash with his good looks and exuberance. The festival will open at the Barbican on 14 March with Hans Pool’s Bellingcat – Truth in a Post-Truth World, which follows the revolutionary rise of the “citizen investigative journalist” collective known as Bellingcat, dedicated to redefining breaking news by exploring the promise of open source investigation.

The festival will open at the Barbican on 14 March with Hans Pool’s Bellingcat – Truth in a Post-Truth World, which follows the revolutionary rise of the “citizen investigative journalist” collective known as Bellingcat, dedicated to redefining breaking news by exploring the promise of open source investigation.

THE GUEST (L’Ospite) ****

THE GUEST (L’Ospite) ****

We spoke to Competition Jury member Lynne Ramsay to talk about her latest project and the film that most impressed her as a child growing up in Glasgow.

We spoke to Competition Jury member Lynne Ramsay to talk about her latest project and the film that most impressed her as a child growing up in Glasgow.

Agnes Varda (b.1928 Belgium)

Agnes Varda (b.1928 Belgium)  Robert De Niro. (b. 1943, US)

Robert De Niro. (b. 1943, US) Dir.: Volker Schlöndorff, Margaretha von Trotta; Cast: Angela Winkler, Mario Adorf, Jürgen Prochnow, Dieter Laser, Heinz Bennett, Hannelore Hoger, Rolf Becker; Federal Republic of Germany 1975, 106’.

Dir.: Volker Schlöndorff, Margaretha von Trotta; Cast: Angela Winkler, Mario Adorf, Jürgen Prochnow, Dieter Laser, Heinz Bennett, Hannelore Hoger, Rolf Becker; Federal Republic of Germany 1975, 106’. Dir: Natalia Meshchaninova | Drama | Russia, Lithuania | 123′

Dir: Natalia Meshchaninova | Drama | Russia, Lithuania | 123′ Russian Film Week is back for the third year running. From 25 November to 2 December the event will take place in London at BFI Southbank, Regent Street Cinema, Curzon Mayfair and Empire Leicester Square before heading to Edinburgh, Cambridge and Oxford.

Russian Film Week is back for the third year running. From 25 November to 2 December the event will take place in London at BFI Southbank, Regent Street Cinema, Curzon Mayfair and Empire Leicester Square before heading to Edinburgh, Cambridge and Oxford. NA-NOO-COBS-NEUN-SAN

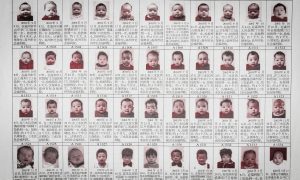

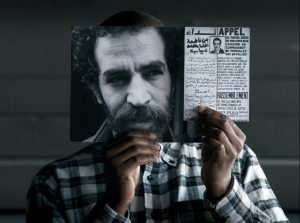

NA-NOO-COBS-NEUN-SAN In Twenty-Two Hours, Bouchra Khalili (left) considers how celebrated French writer Jean Genet was invited by the Black Panther Party to secretly visit them in in the U.S in 1970. The film features Doug Miranda, a former prominent member of the Black Panther Party. Echoing

In Twenty-Two Hours, Bouchra Khalili (left) considers how celebrated French writer Jean Genet was invited by the Black Panther Party to secretly visit them in in the U.S in 1970. The film features Doug Miranda, a former prominent member of the Black Panther Party. Echoing

Moroccan-French artist Bouchra Khalili works with film, video and mixed media. Her focus is on ethnic and political minorities examining the complex relationship between the individual and the community. She is also a Professor of Contemporary Art at The Oslo National Art Academy and a founding member of La Cinematheque de Tanger, an artist-run non-profit organisation based in Tangiers, Morocco. She was the recipient of the Radcliffe Institute Fellowship from Harvard University (2017-2018). Her latest film installation is Twenty-Two Hours (2018).

Moroccan-French artist Bouchra Khalili works with film, video and mixed media. Her focus is on ethnic and political minorities examining the complex relationship between the individual and the community. She is also a Professor of Contemporary Art at The Oslo National Art Academy and a founding member of La Cinematheque de Tanger, an artist-run non-profit organisation based in Tangiers, Morocco. She was the recipient of the Radcliffe Institute Fellowship from Harvard University (2017-2018). Her latest film installation is Twenty-Two Hours (2018). Director Margaret Salmon, who made the hyper realist fantasy drama Eglantine (2016) develops her worthwhile and enchanting filmic forays into the natural world that started with P.S. in 2002, and continued with Everything That Rises Must Converge (2010); Enemies of the Rose (2011); Gibraltar (2013); Pyramid (2014) and Bird (2016), amongst other titles. Very much festival fare, but valuable in their thoughtful exploration of the British Isles, and often further afield. MT

Director Margaret Salmon, who made the hyper realist fantasy drama Eglantine (2016) develops her worthwhile and enchanting filmic forays into the natural world that started with P.S. in 2002, and continued with Everything That Rises Must Converge (2010); Enemies of the Rose (2011); Gibraltar (2013); Pyramid (2014) and Bird (2016), amongst other titles. Very much festival fare, but valuable in their thoughtful exploration of the British Isles, and often further afield. MT

WOMAN AT WAR (2018) – SACD Winner, Cannes Film Festival 2018

WOMAN AT WAR (2018) – SACD Winner, Cannes Film Festival 2018 THE FAVOURITE

THE FAVOURITE

DOGMAN Best Actor, Marcello Forte, Cannes 2018 | Palm Dog Winner 2018

DOGMAN Best Actor, Marcello Forte, Cannes 2018 | Palm Dog Winner 2018  MADELINE’S MADELINE

MADELINE’S MADELINE MUSEUM – Best Script Berlinale 2018

MUSEUM – Best Script Berlinale 2018 IN FABRIC

IN FABRIC THE WILD PEAR TREE – Palme d’Or, Cannes 2018

THE WILD PEAR TREE – Palme d’Or, Cannes 2018  THEY’LL LOVE ME WHEN I’M DEAD (2018)

THEY’LL LOVE ME WHEN I’M DEAD (2018) The first female director to win the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival, Margarethe von Trotta (1942) is to thank for some of the most trailblazing films over the past five decades. Von Trotta’s wonderfully complex and outspoken female characters have undoubtedly inspired those taking centre stage in films by contemporary directors such as Jane Campion, Andrea Arnold, Lynne Ramsay and Lone Scherfig. One of the most gifted – but often overlooked – directors to emerge from the New German Cinema movement at the same time as Rainer Werner Fassbinder and Werner Herzog – von Trotta has never shied away from topics that resonate with contemporary lives and provoke revolutionary discussion. The power of mass media, historical events, radicalisation and women’s rights, have all been visible elements in her films since the politically turbulent 1970s.

The first female director to win the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival, Margarethe von Trotta (1942) is to thank for some of the most trailblazing films over the past five decades. Von Trotta’s wonderfully complex and outspoken female characters have undoubtedly inspired those taking centre stage in films by contemporary directors such as Jane Campion, Andrea Arnold, Lynne Ramsay and Lone Scherfig. One of the most gifted – but often overlooked – directors to emerge from the New German Cinema movement at the same time as Rainer Werner Fassbinder and Werner Herzog – von Trotta has never shied away from topics that resonate with contemporary lives and provoke revolutionary discussion. The power of mass media, historical events, radicalisation and women’s rights, have all been visible elements in her films since the politically turbulent 1970s. ROSA LUXEMBURG (1986)

ROSA LUXEMBURG (1986) THE LOST HONOUR OF KATHARINA BLUM (1975)

THE LOST HONOUR OF KATHARINA BLUM (1975)

Alberto Barbera has announced a stunning line-up of highly anticipated new features and documentaries in celebration of this year’s 71st edition of Venice Film Festival which takes place on the Lido from 28 August until 8 September 2018. 30% of this year’s films are made by women which sounds more positive. Obviously the festival can only programme films offered for screening.

Alberto Barbera has announced a stunning line-up of highly anticipated new features and documentaries in celebration of this year’s 71st edition of Venice Film Festival which takes place on the Lido from 28 August until 8 September 2018. 30% of this year’s films are made by women which sounds more positive. Obviously the festival can only programme films offered for screening. The festival kicks off on the 28th with a remastered 1920 version of THE GOLEM – HOW HE CAME TO BE (ab0ve) complete with musical accompaniment. This year’s festival opening film is Damien Chazelle’s biopic of Neil Armstrong FIRST MAN. There are 21 features and documentaries in the main competition which boasts the latest films from Olivier Assayas (a publishing drama DOUBLE LIVES stars Juliette Binoche), Jacques Audiard (THE SISTERS BROTHERS), Joel and Ethan Coen’s 6-part Western THE BALLAD OF BUSTER SCRUGGS, Brady Corbet’smusical drama VOX LUX; Alfonso Cuaron with ROMA; Luca Guadagnino’s SUSPIRIA sees Tilda Swinton playing 3 parts; Mike Leigh (PETERLOO), Yorgos Lanthimos with an 18th drama entitled THE FAVOURITE; Carlos Reygadas joins from his usual Cannes slot; and Julian Schnabel will present AT ETERNITY’S GATE a drama attempting to get inside the head of Vincent Van Gogh. Not to mention Laszlo Nemes’ Budapest WW1 drama NAPSZÁLLTA, a much awaited second feature and follow up to his Oscar winning Son of Saul.

The festival kicks off on the 28th with a remastered 1920 version of THE GOLEM – HOW HE CAME TO BE (ab0ve) complete with musical accompaniment. This year’s festival opening film is Damien Chazelle’s biopic of Neil Armstrong FIRST MAN. There are 21 features and documentaries in the main competition which boasts the latest films from Olivier Assayas (a publishing drama DOUBLE LIVES stars Juliette Binoche), Jacques Audiard (THE SISTERS BROTHERS), Joel and Ethan Coen’s 6-part Western THE BALLAD OF BUSTER SCRUGGS, Brady Corbet’smusical drama VOX LUX; Alfonso Cuaron with ROMA; Luca Guadagnino’s SUSPIRIA sees Tilda Swinton playing 3 parts; Mike Leigh (PETERLOO), Yorgos Lanthimos with an 18th drama entitled THE FAVOURITE; Carlos Reygadas joins from his usual Cannes slot; and Julian Schnabel will present AT ETERNITY’S GATE a drama attempting to get inside the head of Vincent Van Gogh. Not to mention Laszlo Nemes’ Budapest WW1 drama NAPSZÁLLTA, a much awaited second feature and follow up to his Oscar winning Son of Saul. The out of competition selection is equally exciting and thematically rich. There is Bradley Cooper’s directing debut A STAR IS BORN (left), Charles Manson-themed CHARLIE SAYS from Mary Herron; Amos Gitai’s A TRAMWAY IN JERUSALEM, and Zhang Yimou’s YING (SHADOW). And those whose enjoyed S Craig Zahler’s dynamite Brawl in Cell Block 99 will be pleased to hear that his DRAGGED ACROSS CONCRETE adds Mel Gibson to the previous cast of Jennifer Carpenter and Vince Vaughn. There will be an historic epic set in the time of the French Revolution: UN PEUPLE ET SON ROI features Gaspart Ulliel and Denis Lavant (who also stars in Rick Alverson’s Golden Lion hopeful THE MOUNTAIN) , and Amir Naderi’s MAGIC LANTERN which has the wonderful English talents of Jacqueline Bisset. And talking of England, Mike Leigh’s much gloated over historical epic PETERLOO finally makes it to the competition line-up

The out of competition selection is equally exciting and thematically rich. There is Bradley Cooper’s directing debut A STAR IS BORN (left), Charles Manson-themed CHARLIE SAYS from Mary Herron; Amos Gitai’s A TRAMWAY IN JERUSALEM, and Zhang Yimou’s YING (SHADOW). And those whose enjoyed S Craig Zahler’s dynamite Brawl in Cell Block 99 will be pleased to hear that his DRAGGED ACROSS CONCRETE adds Mel Gibson to the previous cast of Jennifer Carpenter and Vince Vaughn. There will be an historic epic set in the time of the French Revolution: UN PEUPLE ET SON ROI features Gaspart Ulliel and Denis Lavant (who also stars in Rick Alverson’s Golden Lion hopeful THE MOUNTAIN) , and Amir Naderi’s MAGIC LANTERN which has the wonderful English talents of Jacqueline Bisset. And talking of England, Mike Leigh’s much gloated over historical epic PETERLOO finally makes it to the competition line-up EL AMOR MENOS PENSADO

EL AMOR MENOS PENSADO ANGELO

ANGELO DER UNSCHULDIGE / THE INNOCENT

DER UNSCHULDIGE / THE INNOCENT EL REINO

EL REINO ENTRE DOS AGUAS | ISAKI LACUESTA | SPAIN

ENTRE DOS AGUAS | ISAKI LACUESTA | SPAIN  HIGH LIFE.

HIGH LIFE. ILLANG: THE WOLF BRIGADE

ILLANG: THE WOLF BRIGADE LE CAHIER NOIR / THE BLACK BOOK

LE CAHIER NOIR / THE BLACK BOOK QUIÉN TE CANTARÁ

QUIÉN TE CANTARÁ ROJO

ROJO VISION

VISION YULI

YULI In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans traditional jazz musicians gather together to play and talk about the soul of their city which celebrates its 300th Anniversary in 2018.

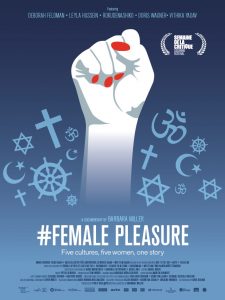

In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans traditional jazz musicians gather together to play and talk about the soul of their city which celebrates its 300th Anniversary in 2018.  Dir: Rebecca Miller | Documentary with Deborah Feldman, Vithika Yadav, Rokudenashiko, Leyla Hussein, Doris Wagner; Germany/Switzerland/UK/USA/Japan 2018, 95 min.

Dir: Rebecca Miller | Documentary with Deborah Feldman, Vithika Yadav, Rokudenashiko, Leyla Hussein, Doris Wagner; Germany/Switzerland/UK/USA/Japan 2018, 95 min. Vagabond

Vagabond

The Closing Night will be the UK Premiere of

The Closing Night will be the UK Premiere of  There will be two retrospectives in honour of non-fiction filmmaking: The innovative found footage documentarian Penny Lane and Japanese pioneer of ‘action documentary’, Kazuo Hara. Both filmmakers will be at the festival to present their work.

There will be two retrospectives in honour of non-fiction filmmaking: The innovative found footage documentarian Penny Lane and Japanese pioneer of ‘action documentary’, Kazuo Hara. Both filmmakers will be at the festival to present their work. Open City Documentary Festival is looking forward to hosting a number of exciting festival parties this year including the Opening and Closing Night Receptions at the Regent Street Cinema as well as the Nabihah Iqbal after-party at the ICA, where the DJ, Producer & NTS Radio presenter presents an evening of music inspired by 1972 documentary Winter Soldier, featuring protest songs and music from the anti-war movement from 1950-1975. Other various festival parties will be listed in the festival programme.

Open City Documentary Festival is looking forward to hosting a number of exciting festival parties this year including the Opening and Closing Night Receptions at the Regent Street Cinema as well as the Nabihah Iqbal after-party at the ICA, where the DJ, Producer & NTS Radio presenter presents an evening of music inspired by 1972 documentary Winter Soldier, featuring protest songs and music from the anti-war movement from 1950-1975. Other various festival parties will be listed in the festival programme. Dir: Rohena Gera | Drama | India | 97′

Dir: Rohena Gera | Drama | India | 97′ An Evening With Beverly Luff Linn (Director: Jim Hosking,

An Evening With Beverly Luff Linn (Director: Jim Hosking, Eighth Grade (Director/Screenwriter: Bo Burnham) – Thirteen-year-old Kayla endures the tidal wave of contemporary suburban adolescence as she makes her way through the last week of middle school — the end of her thus far disastrous eighth grade year — before she begins high school.

Eighth Grade (Director/Screenwriter: Bo Burnham) – Thirteen-year-old Kayla endures the tidal wave of contemporary suburban adolescence as she makes her way through the last week of middle school — the end of her thus far disastrous eighth grade year — before she begins high school. Generation Wealth (Director: Lauren Greenfield) – Lauren Greenfield’s postcard from the edge of the American Empire captures a portrait of a materialistic, image-obsessed culture. Simultaneously personal journey and historical essay, the film bears witness to the global boom–bust economy, the corrupted American Dream and the human costs of late stage capitalism, narcissism and greed.

Generation Wealth (Director: Lauren Greenfield) – Lauren Greenfield’s postcard from the edge of the American Empire captures a portrait of a materialistic, image-obsessed culture. Simultaneously personal journey and historical essay, the film bears witness to the global boom–bust economy, the corrupted American Dream and the human costs of late stage capitalism, narcissism and greed. Half the Picture (Director: Amy Adrion) – At a pivotal moment for gender equality in Hollywood, successful women directors tell the stories of their art, lives and careers. Having endured a long history of systemic discrimination, women filmmakers may be getting the first glimpse of a future that values their voices equally.

Half the Picture (Director: Amy Adrion) – At a pivotal moment for gender equality in Hollywood, successful women directors tell the stories of their art, lives and careers. Having endured a long history of systemic discrimination, women filmmakers may be getting the first glimpse of a future that values their voices equally. Hereditary (Director/Screenwriter: Ari Aster) – After their reclusive grandmother passes away, the Graham family tries to escape the dark fate they’ve inherited.

Hereditary (Director/Screenwriter: Ari Aster) – After their reclusive grandmother passes away, the Graham family tries to escape the dark fate they’ve inherited. Leave No Trace (Director: Debra Granik, Screenwriters: Debra Granik, Anne Rosellini) – A father and daughter live a perfect but mysterious existence in Forest Park, a beautiful nature reserve near Portland, Oregon, rarely making contact with the world. A small mistake tips them off to authorities sending them on an increasingly erratic journey in search of a place to call their own.

Leave No Trace (Director: Debra Granik, Screenwriters: Debra Granik, Anne Rosellini) – A father and daughter live a perfect but mysterious existence in Forest Park, a beautiful nature reserve near Portland, Oregon, rarely making contact with the world. A small mistake tips them off to authorities sending them on an increasingly erratic journey in search of a place to call their own. The Miseducation of Cameron Post (Director: Desiree Akhavan, Screenwriters: Desiree Akhavan, Cecilia Frugiuele) –1993: after being caught having sex with the prom queen, a girl is forced into a gay conversion therapy center. Based on Emily Danforth’s acclaimed and controversial coming-of-age novel.

The Miseducation of Cameron Post (Director: Desiree Akhavan, Screenwriters: Desiree Akhavan, Cecilia Frugiuele) –1993: after being caught having sex with the prom queen, a girl is forced into a gay conversion therapy center. Based on Emily Danforth’s acclaimed and controversial coming-of-age novel. Never Goin’ Back (Director/Screenwriter: Augustine Frizzell) –Jessie and Angela, high school dropout BFFs, are taking a week off to chill at the beach. Too bad their house got robbed, rent’s due, they’re about to get fired and they’re broke. Now they’ve gotta avoid eviction, stay out of jail and get to the beach, no matter what!!!

Never Goin’ Back (Director/Screenwriter: Augustine Frizzell) –Jessie and Angela, high school dropout BFFs, are taking a week off to chill at the beach. Too bad their house got robbed, rent’s due, they’re about to get fired and they’re broke. Now they’ve gotta avoid eviction, stay out of jail and get to the beach, no matter what!!! Skate Kitchen (Director: Crystal Moselle, Screenwriters: Crystal Moselle, Ashlihan Unaldi) – Camille’s life as a lonely suburban teenager changes dramatically when she befriends a group of girl skateboarders. As she journeys deeper into this raw New York City subculture, she begins to understand the true meaning of friendship as well as her inner self.

Skate Kitchen (Director: Crystal Moselle, Screenwriters: Crystal Moselle, Ashlihan Unaldi) – Camille’s life as a lonely suburban teenager changes dramatically when she befriends a group of girl skateboarders. As she journeys deeper into this raw New York City subculture, she begins to understand the true meaning of friendship as well as her inner self. The Tale (Director/Screenwriter: Jennifer Fox) – An investigation into one woman’s memory as she’s forced to re-examine her first sexual relationship and the stories we tell ourselves in order to survive; based on the filmmaker’s own story.

The Tale (Director/Screenwriter: Jennifer Fox) – An investigation into one woman’s memory as she’s forced to re-examine her first sexual relationship and the stories we tell ourselves in order to survive; based on the filmmaker’s own story. Yardie (Director: Idris Elba, Screenwriters: Brock Norman Brock, Martin Stellman) – Jamaica, 1973. When a young boy witnesses his brother’s assassination, a powerful Don gives him a home. Ten years later he is sent on a mission to London. He reunites with his girlfriend and their daughter, but then the past catches up with them. Based on Victor Headley’s novel.

Yardie (Director: Idris Elba, Screenwriters: Brock Norman Brock, Martin Stellman) – Jamaica, 1973. When a young boy witnesses his brother’s assassination, a powerful Don gives him a home. Ten years later he is sent on a mission to London. He reunites with his girlfriend and their daughter, but then the past catches up with them. Based on Victor Headley’s novel. MAY GOD SAVE US | Que Dios nos perdone ****

MAY GOD SAVE US | Que Dios nos perdone **** THE BOOKSHOP ***

THE BOOKSHOP *** CAN’T SAY GOODBYE | No sé decir adiós ***

CAN’T SAY GOODBYE | No sé decir adiós *** ABRACADABRA

ABRACADABRA SUNDAY’S ILLNESS | La enfermedad de los domingos

SUNDAY’S ILLNESS | La enfermedad de los domingos LOTS OF KIDS, A MONKEY AND A CASTLE | Muchos hijos, un mono y un castillo

LOTS OF KIDS, A MONKEY AND A CASTLE | Muchos hijos, un mono y un castillo Wri/Dir: Galina Miklinova | Animation | Czech Rep | 83′

Wri/Dir: Galina Miklinova | Animation | Czech Rep | 83′ Dir: Gabriela Cowperthwaite | Cast: Kate Mara, Ramon Rodriguez, Tom Felton, Bradley Witford, Edie Falco | US Biopic Drama | 116′

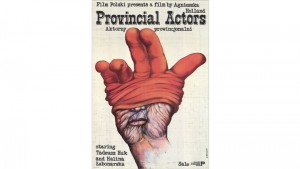

Dir: Gabriela Cowperthwaite | Cast: Kate Mara, Ramon Rodriguez, Tom Felton, Bradley Witford, Edie Falco | US Biopic Drama | 116′ London hosts KINOTEKA Film Festival for the 16th year running. This year celebrates 100 years of Polish independence with the latest cutting edge cinema and some lesser known archival gems now ripe for rediscovery, along with Q&As, masterclasses and musical entertainment. The festival also offers unique insight into Poland’s rich cultural history through cult classics, biopics, women in cinema and a drama from the liberated Nazi concentration camps. And some distinctly contemporary drama that captures the zeitgeist of Poland in the 21st century such as Rafael Kapelinski’s 2017 scabrously dark drama

London hosts KINOTEKA Film Festival for the 16th year running. This year celebrates 100 years of Polish independence with the latest cutting edge cinema and some lesser known archival gems now ripe for rediscovery, along with Q&As, masterclasses and musical entertainment. The festival also offers unique insight into Poland’s rich cultural history through cult classics, biopics, women in cinema and a drama from the liberated Nazi concentration camps. And some distinctly contemporary drama that captures the zeitgeist of Poland in the 21st century such as Rafael Kapelinski’s 2017 scabrously dark drama  The Opening Night Gala commemorates the life of Krzysztof Krauze and his fruitful partnership with wife/co-director, Joanna Kos-Krauze with a screening of Karlovy Vary Award-winning Birds Are Singing in Kigali, a film exploring the life of two women who escape the genocide in Rwanda. There will also be a another chance to see her 2013 biopic drama

The Opening Night Gala commemorates the life of Krzysztof Krauze and his fruitful partnership with wife/co-director, Joanna Kos-Krauze with a screening of Karlovy Vary Award-winning Birds Are Singing in Kigali, a film exploring the life of two women who escape the genocide in Rwanda. There will also be a another chance to see her 2013 biopic drama  This year’s contemporary strand has a particularly focus on female directors. Anna Jadowska’s Wild Roses depicts a mother’s loneliness and struggle to come to terms with her life. Kasia Adamik’s Amok follows the true story of a committed murderer who incriminates himself by writing a novel revealing the killing. There will also be a chance to see the UK premiere of Maria Sadowska’s biopic Sztuka Kochania about the Polish sexologist Michalina Wislocka, who wrote the bestseller The Art of Loving – the first published guide to sexual health from behind the Iron Curtain.

This year’s contemporary strand has a particularly focus on female directors. Anna Jadowska’s Wild Roses depicts a mother’s loneliness and struggle to come to terms with her life. Kasia Adamik’s Amok follows the true story of a committed murderer who incriminates himself by writing a novel revealing the killing. There will also be a chance to see the UK premiere of Maria Sadowska’s biopic Sztuka Kochania about the Polish sexologist Michalina Wislocka, who wrote the bestseller The Art of Loving – the first published guide to sexual health from behind the Iron Curtain. Krzysztof Zanussi will be back again this year ‘in conversation’ about one of his earliest films, The Structure of Crystal (1969) (17 March, ICA). Andrzej Klimowski, one of Polish most celebrated graphic designers will be in town for a masterclass aimed at new and emerging filmmakers looking to create poster artwork. He designed this year’s festival poster.

Krzysztof Zanussi will be back again this year ‘in conversation’ about one of his earliest films, The Structure of Crystal (1969) (17 March, ICA). Andrzej Klimowski, one of Polish most celebrated graphic designers will be in town for a masterclass aimed at new and emerging filmmakers looking to create poster artwork. He designed this year’s festival poster. On 23 March, Kinoteka hosts a gourmet evening featuring the delicious cuisine of rising chef Flavia Borawska, accompanied by a film screening of Krzysztof Kieślowski’s classic Double Life of Veronique.

On 23 March, Kinoteka hosts a gourmet evening featuring the delicious cuisine of rising chef Flavia Borawska, accompanied by a film screening of Krzysztof Kieślowski’s classic Double Life of Veronique.

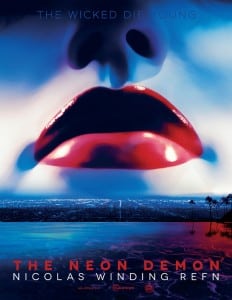

Hollywood may still be struggling with female representation as 2018 gets underway, but Europe has seen tremendous successes in the world of indie film where talented women of all ages are winning accolades in every sphere of the film industry, bringing their unique vision and intuition to a party that has continued to rock throughout the past year. Admittedly, there have been some really fabulous female roles recently – probably more so than for male actors. But on the other side of the camera, women have also created some thumping dramas; robust documentaries and bracingly refreshing genre outings: Lucrecia Martel’s mesmerising Argentinian historical fantasy ZAMA (LFF/left) and Julia Ducournau’s Belgo-French horror drama RAW (below/right) have been amongst the most outstanding features in recent memory. All these films provide great insight into the challenges women continue to face, both personally and in society as a whole, and do so without resorting to worthiness or sentimentality. So as we go forward into another year, here’s a flavour of what’s been happening in 2017.

Hollywood may still be struggling with female representation as 2018 gets underway, but Europe has seen tremendous successes in the world of indie film where talented women of all ages are winning accolades in every sphere of the film industry, bringing their unique vision and intuition to a party that has continued to rock throughout the past year. Admittedly, there have been some really fabulous female roles recently – probably more so than for male actors. But on the other side of the camera, women have also created some thumping dramas; robust documentaries and bracingly refreshing genre outings: Lucrecia Martel’s mesmerising Argentinian historical fantasy ZAMA (LFF/left) and Julia Ducournau’s Belgo-French horror drama RAW (below/right) have been amongst the most outstanding features in recent memory. All these films provide great insight into the challenges women continue to face, both personally and in society as a whole, and do so without resorting to worthiness or sentimentality. So as we go forward into another year, here’s a flavour of what’s been happening in 2017. It all started at SUNDANCE in January where documentarian Pascale Lamche’s engrossing film about Winnie Mandela, WINNIE, won Best World Doc and Maggie Betts was awarded a directing prize for her debut feature NOVITIATE, about a nun struggling to take and keep her vows in 1960s Rome. Eliza Hitman also bagged the coveted directing award for her gay-themed indie drama BEACH RATS, that looks at addiction from a young boy’s perspective.

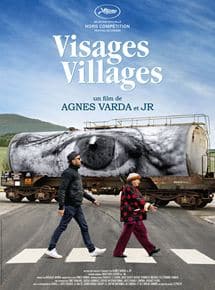

It all started at SUNDANCE in January where documentarian Pascale Lamche’s engrossing film about Winnie Mandela, WINNIE, won Best World Doc and Maggie Betts was awarded a directing prize for her debut feature NOVITIATE, about a nun struggling to take and keep her vows in 1960s Rome. Eliza Hitman also bagged the coveted directing award for her gay-themed indie drama BEACH RATS, that looks at addiction from a young boy’s perspective. Meanwhile, back in Europe, BERLIN‘s Golden Bear went to Hungarian filmmaker Ildiko Enyedi (right) for her thoughtful and inventive exploration of adult loneliness and alienation BODY AND SOUL. Agnieska Holland won a Silver Bear for her green eco feature SPOOR, and Catalan newcomer Carla Simón went home with a prize for her feature debut SUMMER 1993 tackling the more surprising aspects of life for an orphaned child who goes to live with her cousins. CANNES 2017, the festival’s 70th celebration, also proved to be another strong year for female talent. Claire Simon’s first comedy – looking at love in later life – LET THE SUNSHINE IN was well-received and provided a playful role for Juliette Binoche, which she performed with gusto. Agnès Varda’s entertaining travel piece FACES PLACES took us all round France and finally showed Jean-Luc Godard’s true colours, winning awards at TIFF and Cannes. Newcomers were awarded in the shape of Léa Mysius whose AVA won the SACD prize for its tender exploration of oncoming blindness, and Léonor Séraille whose touching drama about the after-effects of romantic abandonment MONTPARNASSE RENDEZVOUS won the Caméra D’Or.

Meanwhile, back in Europe, BERLIN‘s Golden Bear went to Hungarian filmmaker Ildiko Enyedi (right) for her thoughtful and inventive exploration of adult loneliness and alienation BODY AND SOUL. Agnieska Holland won a Silver Bear for her green eco feature SPOOR, and Catalan newcomer Carla Simón went home with a prize for her feature debut SUMMER 1993 tackling the more surprising aspects of life for an orphaned child who goes to live with her cousins. CANNES 2017, the festival’s 70th celebration, also proved to be another strong year for female talent. Claire Simon’s first comedy – looking at love in later life – LET THE SUNSHINE IN was well-received and provided a playful role for Juliette Binoche, which she performed with gusto. Agnès Varda’s entertaining travel piece FACES PLACES took us all round France and finally showed Jean-Luc Godard’s true colours, winning awards at TIFF and Cannes. Newcomers were awarded in the shape of Léa Mysius whose AVA won the SACD prize for its tender exploration of oncoming blindness, and Léonor Séraille whose touching drama about the after-effects of romantic abandonment MONTPARNASSE RENDEZVOUS won the Caméra D’Or. The Doyenne of French contemporary cinema Isabelle Huppert won Best Actress in LOCARNO 2017 for her performance as a woman who morphs from a meek soul to a force to be reckoned with when she is struck by lightening, in Serge Bozon’s dark comedy MADAME HYDE. Huppert has been winning accolades since the 1970s but she still has to challenge Hollywood’s Ann Doran (1911-2000) on film credits (374) – but there is plenty of time!). Meanwhile, Nastassja Kinski was awarded a Lifetime Achievement Honour for her extensive and eclectic contribution to World cinema (Paris,Texas, Inland Empire, Cat People and Tess to name a few).

The Doyenne of French contemporary cinema Isabelle Huppert won Best Actress in LOCARNO 2017 for her performance as a woman who morphs from a meek soul to a force to be reckoned with when she is struck by lightening, in Serge Bozon’s dark comedy MADAME HYDE. Huppert has been winning accolades since the 1970s but she still has to challenge Hollywood’s Ann Doran (1911-2000) on film credits (374) – but there is plenty of time!). Meanwhile, Nastassja Kinski was awarded a Lifetime Achievement Honour for her extensive and eclectic contribution to World cinema (Paris,Texas, Inland Empire, Cat People and Tess to name a few). With a Jury headed by Annette Bening, VENICE again showed women in a strong light. Away from the Hollywood-fraught main competition, this year’s Orizzonti Award was awarded to Susanna Nicchiarelli’s NICO, 1988, a stunning biopic of the final years of the renowned model and musician Christa Pfaffen, played by a feisty Trine Dyrholm. And Sara Forestier’s Venice Days winning debut M showed how a stuttering girl and her illiterate boyfriend help each other overcome adversity. Charlotte Rampling won the prize for Best Actress for her portrait of strength in the face of her husbands’ imprisonment in Andrea Pallaoro’s HANNAH.

With a Jury headed by Annette Bening, VENICE again showed women in a strong light. Away from the Hollywood-fraught main competition, this year’s Orizzonti Award was awarded to Susanna Nicchiarelli’s NICO, 1988, a stunning biopic of the final years of the renowned model and musician Christa Pfaffen, played by a feisty Trine Dyrholm. And Sara Forestier’s Venice Days winning debut M showed how a stuttering girl and her illiterate boyfriend help each other overcome adversity. Charlotte Rampling won the prize for Best Actress for her portrait of strength in the face of her husbands’ imprisonment in Andrea Pallaoro’s HANNAH.  At last but not least, Hong Kong director Vivianne Qu (left/LFF) was awarded the Fei Mei prize at PINGYAO’s inaugural CROUCHING TIGER, HIDDEN DRAGON film festival and the Film Festival of India’s Silver Peacock for her delicately charming feature ANGELS WEAR WHITE that deftly raises the harrowing plight of women facing sexual abuse in the mainland. It seems that this is a hot potato the superpowers of China and US still have in common. But on a positive note, LADYBIRD Greta Gerwig’s first film as a writer and director, has been sweeping the boards critically all over the US and is the buzzworthy comedy drama of 2018 (coming in February). So that’s something else to look forward to. MT

At last but not least, Hong Kong director Vivianne Qu (left/LFF) was awarded the Fei Mei prize at PINGYAO’s inaugural CROUCHING TIGER, HIDDEN DRAGON film festival and the Film Festival of India’s Silver Peacock for her delicately charming feature ANGELS WEAR WHITE that deftly raises the harrowing plight of women facing sexual abuse in the mainland. It seems that this is a hot potato the superpowers of China and US still have in common. But on a positive note, LADYBIRD Greta Gerwig’s first film as a writer and director, has been sweeping the boards critically all over the US and is the buzzworthy comedy drama of 2018 (coming in February). So that’s something else to look forward to. MT