Matthew Turner spoke to André Semenza, the director of SEA WITHOUT SHORE which has its World premiere at this year’s GLASGOW FILM FESTIVAL 2105

Fragments of theatre, dance, cinema and poetry co-mingle in this unique and ravishing film, tell us more…

André Semenza (AS): It came about through the rehearsal studio. Fernanda Lippi, the choreographer, and I have worked together since 1999 and also with the Director of Photography, Marcus Waterloo. We have a particular way of working which is almost like improvised theatre, where we work in a rehearsal room and explore things with dances and find themes and have visions. It’s a very intuitive and collaborative kind of process where things start taking shape. So there was a relationship between these two women, Fernanda and Livia, the dancer. Clearly something was happening between them and there was some dramatic material emerging and we started piecing that together, like any script, but in a slightly more intuitive manner. And then I had a vision that we should do it in Sweden – my mother was Swedish and I had visions of horses and people draped over horses. So we started location scouting and it was sort of like a quest into the unknown, really, the search for discovery goes all the way through to post-production when we actually review some of the footage and are surprised by some things. Marcus and I both come from a film background where film used to be very precious, so we’re quite efficient, it’s not just like shooting blindly, although we didn’t have a script or a shot list. We were just looking for stuff that is of interest and has potential and often when you’re able to just hang in a little bit longer, something else happens which is often surprising, whether it’s the performer or the actor gives something extra that we didn’t quite expect. It’s quite real and quite raw, so we had great respect for that, creating the space for this to happen.

You mentioned that you had visions of horses. Where did they come from?

You mentioned that you had visions of horses. Where did they come from?

AS: Yes. I was sitting in the rehearsal room with Fernanda and Livia – it was a community centre in London that we were using – and I just had these visions of horses, I started drawing horses that these two women would be draped over. We could have done it in England, we were looking at locations, but I just had this inkling we should do it in Sweden.

How did you find those incredible locations, particularly the house?

AS: So we did location scouting there and the thing just sort of snowballed in a very organic manner. We were actually approached by a Brazilian who lives in Sweden who liked our work, he offered to be our location scout. His girlfriend, her brother had access to these incredible locations, the house where we shot it is a family property, it was called the White House, 19th century, it’s an astonishing place, it’s untouched. So we found records on location that we used in the film, the old 1910 records and the wallpaper, it just completely married with the theme of the film. So when you put your neck out there as a director and a producer and you don’t have location scouts and you actually do that yourself, people engage with you much more, in a different manner. And I also shot in an area in the summer where I have ancestry going back 600 years – I’m a strange European mix – but suddenly people came out of the woodwork who knew my great grandfather or something and things just kind of happened. It’s a different process – you put yourself out there and somehow it pulls you back in, to places that you didn’t expect.

Whereabouts was the house?

Whereabouts was the house?

AS: It’s on one of the islands outside Stockholm. It’s basically owned by this person who we met briefly through this connection. He was extremely generous – he also took us to his mother’s house and just invited us to stay there for a month, ‘Oh, I’m going to Colombia, here’s the key’ – he’d met us for ten minutes! And then this fella’s uncle became the co-producer in Sweden, he found all these Pagan sites where we wanted to film – we were looking for Pagan circles and things like that where we could work with an agnostic theme of this woman looking for her beloved soul that disappeared. And he was a very, very quiet guy, and he said, ‘Yeah, I know a place’ and there was this place, walking distance, which was a sort of a circle where nothing grows and it’s been a sacred site for thousands of years. He asked the girls to take off their gloves and they were warm! It was minus ten! It was all rather odd, but there is a sense of adventure when you work like that and I think it triggers other people’s imaginations as well. And then of course my job and Fernanda’s job is to hone it, to unify that. Because of course, many ideas that we come up with are rubbish, even my own – you try and cling to your own ideas, but actually you have to drop them and all that. So in the end you have something that’s very organic, where the performances, the bodies, the costumes, the wallpaper, the lighting, everything should be – I don’t want to sound pretentious but the gesamtkunstwerk, the whole sensorial experience, covering all the senses, plus the intellect as well. I’m not really a Wagner fan, but he thought opera was it and then cinema became it, where if you’re open to going on a journey you can really have a very sensorial and an intellectual complete experience.

Who or what were your main influences? My editor felt that your film echoed Hungarian director, Gábor Bódy’s Nárcisz és Psyché…

AS: Really? I don’t know that film. Fernanda and I have a physical theatre company together as well, so I’ve always been interested in Grotowski, the Polish theatre giant, Peter Brook was a huge fan. His stuff was very physical but not in a cathartic way, it’s extremely controlled, but you’d see this quite shocking stuff and every night was the same. Technically phenomenal. So I was always interested in that and Fernanda, coming from Trinity Laban [Conservatoire of Music and Dance], having that experience married very well with these sort of things. And of course I trained, Stanislavsky, whatever, so that’s the performance side of things. And from the cinema point of view, I think my greatest influence perhaps was Tarkovsky, I think that’s one of the most shocking experiences I’ve ever had. And of course Ingmar Bergman, speaking Swedish as well. Especially with this film, the voiceover is in Swedish and there’s definitely a Nordic tempo in it. Many film people probably have a similar list of film cinema influences to mine, the Ozus and the Godards and so on, but I think for this film, Tarkovsky and Bergman would be big influences. Dreyer too, Ordet is devastating stuff. Early Fritz Lang too.

How did co-directing with Fernanda work in practice? Were you responsible for different elements?

How did co-directing with Fernanda work in practice? Were you responsible for different elements?

AS: Well, we did a film before, Ashes of God, in 2003 and I was the director and she was the choreographer. But we felt in this project, because she conceived so much in the rehearsal room – I’m very much the film side of things, the choice of shots with markers, I also edited and so on, but her influence is a deep understanding of the emotional story, sometimes she would have incredible insights and she was just there from the very beginning when it was just people flopping around in a studio looking rather rubbish and then shooting stuff from the beginning and it still looked very rubbish, but then just like nursing it through and being a real coach to the cast, to Livia and to [Anna Mesquita] in particular and of course doing her own work as well. So it’s a situation where we don’t step on each other’s feet at all – she provides material and I can then give my own guidance or input, but she’s not precious about, ‘Oh, you have to shoot all the choreography’ – if you work with a famous choreographer, you have to cover the whole thing and every dancer has to be in shot, so it’s not really cinema, it’s nothing to do with cinema. So it’s very much surrendering all the material to the camera and what the camera falls in love with, and Marcus, the cameraman, is very intuitive as well, so we have this triangular co-creation, shall we say, going on.

And you also did the editing yourself. What was that process like?

AS: I was very concerned about editing myself, because I’m aware that some directors, when they edit, they get very self-indulgent and stuff just rambles on forever, but what we did was basically, I was editing and then I’d put it on DVD, not look at it for a week and then watch it with Fernanda in a different context. And she would be the “Paramount Pictures person”, she would be the outside view, we would talk about it and she would see stuff that maybe I had missed. And of course, I was able to distance myself and have a new appraisal of it, so I’m actually very happy with the edit. Of course, it requires certain patience, it’s not MTV editing, it’s classical stuff, but when I look at the cuts now, the timing is just right. And it was just a slow, patient process like that.

Were Fernanda and Livia always going to play those roles? Was there a casting process?

AS: Livia had worked with us in other productions before, live productions, and we always wanted to make a film project together. She came from Brazil with us and that was the cast. In Stockholm, we approached a senior dancer for that third role and she was unable to do it, but then the person who was approaching her was actually a young dancer herself and we looked at her and thought, ‘Why don’t we try Anna?’ – she’s half Brazilian, half Swedish. It was a very happy coincidence, in a way. So we didn’t have a proper casting in that sense.

So all the cast members were primarily dancers?

So all the cast members were primarily dancers?

AS: Yes, apart from the lady who works with horses, who is a horse person, really. She used to be a designer, but now she has a farm for horses on their last legs, so to speak, post-career horses. So she was just providing that side of things.

Movement is obviously a very important part of the film – how collaborative was that process? AS you say, Fernanda was the choreographer, but did you work with Fernanda on the movements as the director?

AS: We have very similar taste, Fernanda and I, so we get excited about the same stuff, which is very useful. From my point of view, if I don’t believe something, it’s not going to make it [into the film], it has to be believable, it has to be authentic, even if it’s strange. So that’s always been my filter. I’m not really a contemporary dance person, I don’t really like a lot of contemporary dance, or the vanity, all that nonsense – it’s very much about performance and authenticity and when you capture something it’s a privilege, you feel it’s really tremendous, it’s a unique moment. In terms of editing, as an editor, it’s very much a new choreographic process, shots were slowed down, maybe 80 clips were slowed down, sometimes noticeably, other times not, and the juxtaposition and the breathing, the sense of rhythm is very choreographic, I think, as well. So I’m very much interested in movement. And in terms of the movement of the dance, it should not be a dance film, you know, breaking out in dance, it’s not a musical in that sense – it’s very much an externalisation of these compulsive, almost autistic kind of movements where the person is bereft and at a loss. And I think these movements are quite rooted in this person as well, in Livia, she brought that to the role, so we were able to use some of that material. And so when she dances by herself, it’s a memory, she re-enacts part of what she remembers, and then when she rocks, that’s very much an autistic, kind of lonely thing to do. So I think it should really be, again, not sticking out as ‘Hmm, this is a bit of a dance moment’, but actually being integrated as a whole in the story.

The film presents a narrative of doomed love from a female perspective, but is there a male perspective or is it exclusively female?

AS: Hmm. [long pause] It’s a difficult question, I don’t really know how to [answer that]. For me, I very much identified with that sense of loss. I actually lost my mum in 2005, which was just literally a week after the winter shoot. And of course that grief went into the film. So it’s a feminine film, I think, but also, it’s very hard, because my taste, our live work is quite shocking sometimes, not for the shock value itself, but just because it’s quite visceral. And also, Andrew Mckenzie’s work, the composer, from the beginning, he recorded the dancers’ performance and then created a twenty minute track that was then used in further rehearsals and on location, so they’re using their own sound and it becomes almost esoteric and quite mysterious. His stuff is quite shocking too – shocking is the wrong word, it would silence people, in a good sense. Which I think is what I’ve always loved, when I saw, let’s say Fritz Lang’s M for the first time, I couldn’t speak for two days. You don’t go outside and go, ‘Oh, that was nice’, you’re like [stares, open-mouthed], you want to stay through the credits and that sensation stays with you for some time. And I think Andrew’s music has that effect. As an artist, you always aspire to reach something like that. If you see a Mark Rothko, you feel something beyond just paint and the shapes. Something transcendent, maybe that’s the word.

What was the most challenging aspect of the production? What was the hardest thing to get right?

AS: There were lots of challenges on the shoot, but I see them as adventurous challenges, you know, like getting the boat and the ice-breaker, living in a house with no heating, all huddled together at night, shaking with the cold – all these things were tough, but not in a negative sense, they were part of the experience, of reaching the peak of the mountain, or whatever. But the tough thing really is the editing, when you start putting things together, when you start marrying the summer stuff with the winter stuff, it’s dreadful, you don’t really feel it’s going to work and then suddenly something gives. Editing can be quite a lonely and depressing place, sometimes, but the most difficult part for me, personally, was pushing it through the technological development, because we shot on a format which has now been surpassed, and then getting it through to the DCP, all that process was a real challenge, to be honest. Basically, what we did with Ashes of God, we shot that on digital as well, but went to film and it looked like a film, astonishingly, from DDV cam, it was like 35mm, massively blown up and nobody noticed that it was not film. And all of this was because emulsion is forgiving, but if you don’t have that process and you go from digital through to the final product and you don’t have that emulsion, you will see all the mistakes, all the artefacts, so we worked very hard to minimise that. And that was a long, long process, I’d say two years. Jumping through lots of programs and then you’re losing quality. We ended up doing it in Pinewood with a phenomenal, wonderful grader, who had recently restored lots of BBC films, Martin Greenback and he was just utterly patient and just fantastic. He really saved us.

Did you cut anything out during the editing process that you were sorry to see go?

AS: Well, yes, a lot of the poetry, some of the wonderful lines that we had – [Algernon Charles] Swinburne primarily, but also Katherine Philips, who was a 17th century lesbian poet, and also Renée Vivien. So some of these lines were great, but they just would not stick, or they would be doubling up the message and it would just be a bit too much of a good thing, so they had to go. Sometimes less is more and all that stuff. There were some dance scenes where we actually got a whole bunch of local dancers to dance for us, traditional dance, Midsummer Night’s Dance, wonderful stuff in Sweden, if you think of Miss Julie and all that stuff. And they’re not in the film – it just didn’t look right. We worked very hard to try and make it work, but all we have left is a bit of music in the background.

How did you go about choosing the text for the film and did you write any original text for the film?

AS: Yes, we did. Basically we wrote the stuff which I thought was too on the nose. Fernanda wrote some beautiful stuff which had to do with her sister, in fact. And that was very much of interest. And then I started reading massive anthologies of lesbian literature, from the 1500s onwards, and I came across a lot of interesting people, including Katherine Philips and I stumbled upon Anactoria by Swinburne, which is Sappho speaking to Anactoria and he’s a great poet and it’s wild stuff. And somehow that really reverberated. So it was a collage of fragments that I brought in, about thirty pages. And then I felt that it should be in Swedish, because these women are in Sweden and you could logically justify it in that, for instance, Renée Vivien was English and she was blue-blooded and inherited a massive fortune, and she had a massive fight with her mother, so much so that she left for France and just abandoned her Englishness and spoke French and wrote in French. So it felt like these are clearly not Swedish women, they are South American women in Sweden, looking for a kind of Pagan liberation, perhaps getting away from the macho South American world and so on. So I felt it should be in Swedish, but this was all very intuitive stuff, so I sent it to a great translator that somebody recommended and when I got the translation back, I just burst into laughter with pleasure, because she had actually managed to capture the essence of the poetry and in some cases even improved on it, if I may say so. I hope Swinburne’s not listening! But it was just, ‘Wow, this is great!’ And then, recording this, we had a Chilean Swedish lady doing a lot of the voiceover, with a great voice, and also Fernanda. Fernanda doesn’t speak a word of Swedish, and she didn’t even want to know the meaning of the sentences, and I was coaching her, and I actually felt that it was great that she didn’t know, because she would just deliver it without intention. I felt that was a very interesting way, almost like an Ozu or a Bresson way of approaching acting, where you strip things of meaning and emotion and just get the purity. So Fernanda was just repeating after me, like a parrot, so it had a very hypnotic quality, to me, and, I felt, a musical quality. So there were all kinds of factors, the voiceover script is also a musical score, I feel. It ranges, and it gives the passion, the rage, the loss, the tenderness, all the kind of things that you have in a love relationship, but also, because of the voices and the South American vibrato of the voices, there is a kind of musical quality, it goes into the music track, really.

Do you see it as a lesbian film in particular?

AS: Yes, lesbian, but not with a capital L. It’s very much about human beings, you know, it’s clearly a love story between two women, but we’re not really carrying the flag or something like that. In a lot of my work, sometimes there are gay characters and so on, so it is a lesbian film, yeah, but with a lower case L.

What’s your next project?

AS: I have two films to finish, that we shot in Brazil. They’re smaller films, but they’re dance / physical theatre films. And we have a film that we want to revive, that I raised finance for in the 90s, a great, great project, it was a triangular relationship, a psychological drama, with Lothaire Bluteau, from Jesus of Montreal. So I’m very keen to revive it now, but setting it a century earlier, because we’re very much into this late, decadent poetics kind of thing. We’ve gone to many congresses and become very friendly with these academics and studied these water painters and Oscar Wildes and Swinburnes and it’s just a very, very interesting world where I felt that the late Victorians, these guys really pushed the boat out, they were the punks of the time, so if we put this story in 1890s Britain, I think it would be very interesting. So that will be the next project.

[youtube id=”V17y1SYuyTs” width=”600″ height=”350″]

SEA WITHOUT SHORE | WORLD PREMIERE | GLASGOW FILM FESTIVAL 2015

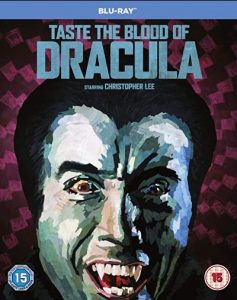

Atmospherically directed by Hungarian Peter Sasdy, and adapted for the screen by Anthony Hinds – stepping in due to budgetary constraints under the pseudonym of John Elder (he told his neighbours he was a hairdresser to avoid publicity throughout his entire career) this outing actually broadens the storyline into a damning social satire of Victorian repression and upper class ennui. The eclectic cast has Christopher Lee, Geoffrey Keen and Gwen Watford and sees three distinguished English gentlemen (Keen, Peter Sallis and John Carson) descend into Satanism, for want of anything better to do, accidentally killIng Dracula‘s sidekick Lord Courtly (Ralph Bates), in the process. As an act of revenge the Count vows they will die at the hands of their own children. But Lee actually bloodies the waters in the second half, swanning in glowering due to his lack of a domineering role in the proceedings.

Atmospherically directed by Hungarian Peter Sasdy, and adapted for the screen by Anthony Hinds – stepping in due to budgetary constraints under the pseudonym of John Elder (he told his neighbours he was a hairdresser to avoid publicity throughout his entire career) this outing actually broadens the storyline into a damning social satire of Victorian repression and upper class ennui. The eclectic cast has Christopher Lee, Geoffrey Keen and Gwen Watford and sees three distinguished English gentlemen (Keen, Peter Sallis and John Carson) descend into Satanism, for want of anything better to do, accidentally killIng Dracula‘s sidekick Lord Courtly (Ralph Bates), in the process. As an act of revenge the Count vows they will die at the hands of their own children. But Lee actually bloodies the waters in the second half, swanning in glowering due to his lack of a domineering role in the proceedings.

A sense of the Gothic also infiltrates No Room at the Inn set in the early months of 1940. We witness atmospheric blitzed streets by the railway bridge next to a rundown house that’s definitely on the wrong side of the tracks: all lorded over by Mrs Agatha Voray (Freda Jackson) doing her damn best not to properly look after three young girl evacuees. The children live in squalor and suffer mental and physical abuse under the care of this coarse woman who invites men (local councillors and shopkeepers) for casual sex and bit of cash to bolster her shopping allowance of ration coupons.

A sense of the Gothic also infiltrates No Room at the Inn set in the early months of 1940. We witness atmospheric blitzed streets by the railway bridge next to a rundown house that’s definitely on the wrong side of the tracks: all lorded over by Mrs Agatha Voray (Freda Jackson) doing her damn best not to properly look after three young girl evacuees. The children live in squalor and suffer mental and physical abuse under the care of this coarse woman who invites men (local councillors and shopkeepers) for casual sex and bit of cash to bolster her shopping allowance of ration coupons.

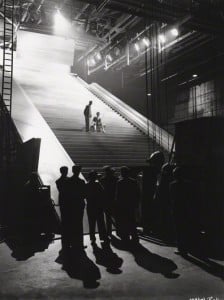

Films don’t always end up the way their makers originally envisaged at their outset, and the maiden production of Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger’s Archers Films would have turned out completely differently had Laurence Olivier been freed from the Fleet Air Arm to make it; since it is now impossible to imagine without third-billed Roger Livesey and his distinctive voice in the title role (in which at the age of 36 he convincingly ages forty years). The makers’ relative inexperience shows in the fact that they ended up with a initial cut over two and a half hours long; but fortunately J.Arthur Rank liked the film so much he let it hit cinemas as it was. Indeed, it was Pressburger’s favourite of the Rank outings, and would go on to influence the work of future filmmakers such as Scorsese in his The Age of Innocence and Tarantino who copied the device of beginning and ending a film be rerunning the same scene from the point of view of different characters.

Films don’t always end up the way their makers originally envisaged at their outset, and the maiden production of Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger’s Archers Films would have turned out completely differently had Laurence Olivier been freed from the Fleet Air Arm to make it; since it is now impossible to imagine without third-billed Roger Livesey and his distinctive voice in the title role (in which at the age of 36 he convincingly ages forty years). The makers’ relative inexperience shows in the fact that they ended up with a initial cut over two and a half hours long; but fortunately J.Arthur Rank liked the film so much he let it hit cinemas as it was. Indeed, it was Pressburger’s favourite of the Rank outings, and would go on to influence the work of future filmmakers such as Scorsese in his The Age of Innocence and Tarantino who copied the device of beginning and ending a film be rerunning the same scene from the point of view of different characters.

L

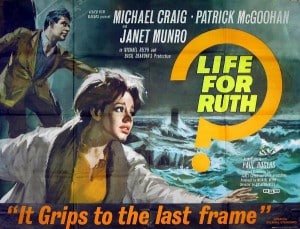

L Dir: Joseph Losey | 97′ UK Crime drama

Dir: Joseph Losey | 97′ UK Crime drama

Dir: John Guillermin | Script: Bryan Forbes | Cast: M E Clifton Jones, John Mills, Maureen Connell, Cecil Parker, Patrick Allen, Leslie Philips, Barbara Hicks, Sidney James, John Le Mesurier, Marius Goring, Michael Hordern | War Drama | UK 101′

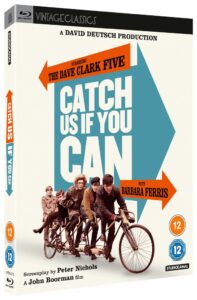

Dir: John Guillermin | Script: Bryan Forbes | Cast: M E Clifton Jones, John Mills, Maureen Connell, Cecil Parker, Patrick Allen, Leslie Philips, Barbara Hicks, Sidney James, John Le Mesurier, Marius Goring, Michael Hordern | War Drama | UK 101′ Dir: Richard Lester | Writer: Charles Wood | Cast: John Lennon, Roy Kinnear, Michael Crawford, Michael Hordern, Jack MacGowran | UK Comedy 109′

Dir: Richard Lester | Writer: Charles Wood | Cast: John Lennon, Roy Kinnear, Michael Crawford, Michael Hordern, Jack MacGowran | UK Comedy 109′ What could be more romantic than a train journey? Even if it feels more like a boys own adventure, as many of these British Transport films do. Escaping into the unknown with a promise of excitement and discovery – or just a trip back in time to revisit childhood holidays in the 1960s and 1970s, where the English landscape stretched far and wide from the window of the pullman out of Waterloo, or even Paddington, and not an anorak in sight!

What could be more romantic than a train journey? Even if it feels more like a boys own adventure, as many of these British Transport films do. Escaping into the unknown with a promise of excitement and discovery – or just a trip back in time to revisit childhood holidays in the 1960s and 1970s, where the English landscape stretched far and wide from the window of the pullman out of Waterloo, or even Paddington, and not an anorak in sight!  The four Palme d’Or hopefuls directed by women are— Mati Diop’s Atlantique (she was memorable in

The four Palme d’Or hopefuls directed by women are— Mati Diop’s Atlantique (she was memorable in Jury

Jury

We spoke to Competition Jury member Lynne Ramsay to talk about her latest project and the film that most impressed her as a child growing up in Glasgow.

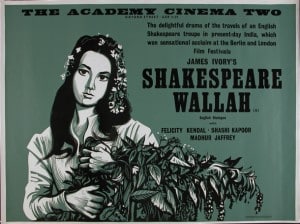

We spoke to Competition Jury member Lynne Ramsay to talk about her latest project and the film that most impressed her as a child growing up in Glasgow. Dir: Tony Richardson | Writers: Shelagh Delaney, Tony Richardson | Cast: Rita Tushingham, Murray Melvin, Dora Bryan, John Danquah, Robert Stephens | UK | Drama | 101′

Dir: Tony Richardson | Writers: Shelagh Delaney, Tony Richardson | Cast: Rita Tushingham, Murray Melvin, Dora Bryan, John Danquah, Robert Stephens | UK | Drama | 101′ KHARTOUM is the kind of spectacular, rousing historical adventure that doesn’t get made anymore, certainly not along the same lines as Basil Dearden’s star-studded epic that exposes English colonialism, religious fanaticism, heroism and sacrifice in a magnificent visual masterpiece. Back in the day, it all seemed perfectly harmless to our innocent childhood eyes as we sat round the telly oblivious to the political incorrectness. And that wasn’t the worst thing: it later emerged that over a hundred horses were severely injured or killed immediately during the battle scenes, due to unethical stunt methods of the time.

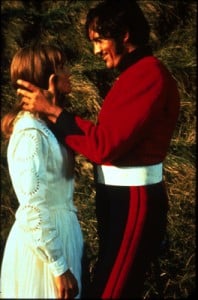

KHARTOUM is the kind of spectacular, rousing historical adventure that doesn’t get made anymore, certainly not along the same lines as Basil Dearden’s star-studded epic that exposes English colonialism, religious fanaticism, heroism and sacrifice in a magnificent visual masterpiece. Back in the day, it all seemed perfectly harmless to our innocent childhood eyes as we sat round the telly oblivious to the political incorrectness. And that wasn’t the worst thing: it later emerged that over a hundred horses were severely injured or killed immediately during the battle scenes, due to unethical stunt methods of the time. John Schlesinger’s YANKS, a moving and romantic WWII tale of love starring Richard Gere and Vanessa Redgrave is based on Lancashire born Colin Welland’s original story, he also wrote the script.

John Schlesinger’s YANKS, a moving and romantic WWII tale of love starring Richard Gere and Vanessa Redgrave is based on Lancashire born Colin Welland’s original story, he also wrote the script. Dir.: Simon Hunter; Cast: Sheila Hancock, Kevin Guthrie, Amy Mason, Wendy Morgan; UK 2017, 102 min.

Dir.: Simon Hunter; Cast: Sheila Hancock, Kevin Guthrie, Amy Mason, Wendy Morgan; UK 2017, 102 min. Director Margaret Salmon, who made the hyper realist fantasy drama Eglantine (2016) develops her worthwhile and enchanting filmic forays into the natural world that started with P.S. in 2002, and continued with Everything That Rises Must Converge (2010); Enemies of the Rose (2011); Gibraltar (2013); Pyramid (2014) and Bird (2016), amongst other titles. Very much festival fare, but valuable in their thoughtful exploration of the British Isles, and often further afield. MT

Director Margaret Salmon, who made the hyper realist fantasy drama Eglantine (2016) develops her worthwhile and enchanting filmic forays into the natural world that started with P.S. in 2002, and continued with Everything That Rises Must Converge (2010); Enemies of the Rose (2011); Gibraltar (2013); Pyramid (2014) and Bird (2016), amongst other titles. Very much festival fare, but valuable in their thoughtful exploration of the British Isles, and often further afield. MT Dir: Richard Marquand | Cast: Donald Sutherland, Kate Nelligan, Christopher Cazenove, | Action Drama | UK |

Dir: Richard Marquand | Cast: Donald Sutherland, Kate Nelligan, Christopher Cazenove, | Action Drama | UK | The lineup for the 2018 BFI London Film Festival has been announced, and the public box office is open. The 12-day festival will show over 225 feature-length films from all over the globe – so here are some of the best we’ve seen from this year’s international festival circuit.

The lineup for the 2018 BFI London Film Festival has been announced, and the public box office is open. The 12-day festival will show over 225 feature-length films from all over the globe – so here are some of the best we’ve seen from this year’s international festival circuit.

WOMAN AT WAR (2018) – SACD Winner, Cannes Film Festival 2018

WOMAN AT WAR (2018) – SACD Winner, Cannes Film Festival 2018 THE FAVOURITE

THE FAVOURITE

DOGMAN Best Actor, Marcello Forte, Cannes 2018 | Palm Dog Winner 2018

DOGMAN Best Actor, Marcello Forte, Cannes 2018 | Palm Dog Winner 2018  MADELINE’S MADELINE

MADELINE’S MADELINE MUSEUM – Best Script Berlinale 2018

MUSEUM – Best Script Berlinale 2018 IN FABRIC

IN FABRIC THE WILD PEAR TREE – Palme d’Or, Cannes 2018

THE WILD PEAR TREE – Palme d’Or, Cannes 2018  THEY’LL LOVE ME WHEN I’M DEAD (2018)

THEY’LL LOVE ME WHEN I’M DEAD (2018) Alberto Barbera has announced a stunning line-up of highly anticipated new features and documentaries in celebration of this year’s 71st edition of Venice Film Festival which takes place on the Lido from 28 August until 8 September 2018. 30% of this year’s films are made by women which sounds more positive. Obviously the festival can only programme films offered for screening.

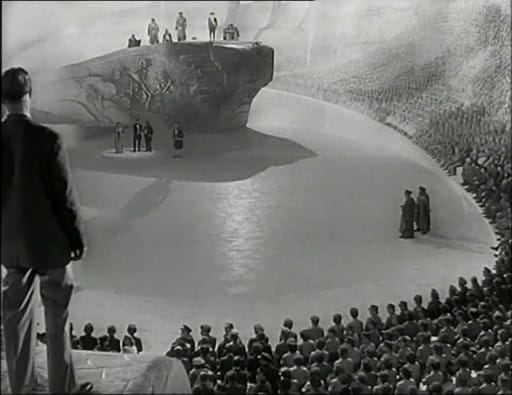

Alberto Barbera has announced a stunning line-up of highly anticipated new features and documentaries in celebration of this year’s 71st edition of Venice Film Festival which takes place on the Lido from 28 August until 8 September 2018. 30% of this year’s films are made by women which sounds more positive. Obviously the festival can only programme films offered for screening. The festival kicks off on the 28th with a remastered 1920 version of THE GOLEM – HOW HE CAME TO BE (ab0ve) complete with musical accompaniment. This year’s festival opening film is Damien Chazelle’s biopic of Neil Armstrong FIRST MAN. There are 21 features and documentaries in the main competition which boasts the latest films from Olivier Assayas (a publishing drama DOUBLE LIVES stars Juliette Binoche), Jacques Audiard (THE SISTERS BROTHERS), Joel and Ethan Coen’s 6-part Western THE BALLAD OF BUSTER SCRUGGS, Brady Corbet’smusical drama VOX LUX; Alfonso Cuaron with ROMA; Luca Guadagnino’s SUSPIRIA sees Tilda Swinton playing 3 parts; Mike Leigh (PETERLOO), Yorgos Lanthimos with an 18th drama entitled THE FAVOURITE; Carlos Reygadas joins from his usual Cannes slot; and Julian Schnabel will present AT ETERNITY’S GATE a drama attempting to get inside the head of Vincent Van Gogh. Not to mention Laszlo Nemes’ Budapest WW1 drama NAPSZÁLLTA, a much awaited second feature and follow up to his Oscar winning Son of Saul.

The festival kicks off on the 28th with a remastered 1920 version of THE GOLEM – HOW HE CAME TO BE (ab0ve) complete with musical accompaniment. This year’s festival opening film is Damien Chazelle’s biopic of Neil Armstrong FIRST MAN. There are 21 features and documentaries in the main competition which boasts the latest films from Olivier Assayas (a publishing drama DOUBLE LIVES stars Juliette Binoche), Jacques Audiard (THE SISTERS BROTHERS), Joel and Ethan Coen’s 6-part Western THE BALLAD OF BUSTER SCRUGGS, Brady Corbet’smusical drama VOX LUX; Alfonso Cuaron with ROMA; Luca Guadagnino’s SUSPIRIA sees Tilda Swinton playing 3 parts; Mike Leigh (PETERLOO), Yorgos Lanthimos with an 18th drama entitled THE FAVOURITE; Carlos Reygadas joins from his usual Cannes slot; and Julian Schnabel will present AT ETERNITY’S GATE a drama attempting to get inside the head of Vincent Van Gogh. Not to mention Laszlo Nemes’ Budapest WW1 drama NAPSZÁLLTA, a much awaited second feature and follow up to his Oscar winning Son of Saul. The out of competition selection is equally exciting and thematically rich. There is Bradley Cooper’s directing debut A STAR IS BORN (left), Charles Manson-themed CHARLIE SAYS from Mary Herron; Amos Gitai’s A TRAMWAY IN JERUSALEM, and Zhang Yimou’s YING (SHADOW). And those whose enjoyed S Craig Zahler’s dynamite Brawl in Cell Block 99 will be pleased to hear that his DRAGGED ACROSS CONCRETE adds Mel Gibson to the previous cast of Jennifer Carpenter and Vince Vaughn. There will be an historic epic set in the time of the French Revolution: UN PEUPLE ET SON ROI features Gaspart Ulliel and Denis Lavant (who also stars in Rick Alverson’s Golden Lion hopeful THE MOUNTAIN) , and Amir Naderi’s MAGIC LANTERN which has the wonderful English talents of Jacqueline Bisset. And talking of England, Mike Leigh’s much gloated over historical epic PETERLOO finally makes it to the competition line-up

The out of competition selection is equally exciting and thematically rich. There is Bradley Cooper’s directing debut A STAR IS BORN (left), Charles Manson-themed CHARLIE SAYS from Mary Herron; Amos Gitai’s A TRAMWAY IN JERUSALEM, and Zhang Yimou’s YING (SHADOW). And those whose enjoyed S Craig Zahler’s dynamite Brawl in Cell Block 99 will be pleased to hear that his DRAGGED ACROSS CONCRETE adds Mel Gibson to the previous cast of Jennifer Carpenter and Vince Vaughn. There will be an historic epic set in the time of the French Revolution: UN PEUPLE ET SON ROI features Gaspart Ulliel and Denis Lavant (who also stars in Rick Alverson’s Golden Lion hopeful THE MOUNTAIN) , and Amir Naderi’s MAGIC LANTERN which has the wonderful English talents of Jacqueline Bisset. And talking of England, Mike Leigh’s much gloated over historical epic PETERLOO finally makes it to the competition line-up Dir: Billy Wilder | Writers: Billy Wilder, Harry Kurnitz, Lawrence B Marcus | Cast: Marlene Dietrich, Tyrone Power, Charles Laughton, Elsa Lanchester, John Williams, Torin Thatcher, Norma Varden, Una O’Connor | US Crime Drama | 116′

Dir: Billy Wilder | Writers: Billy Wilder, Harry Kurnitz, Lawrence B Marcus | Cast: Marlene Dietrich, Tyrone Power, Charles Laughton, Elsa Lanchester, John Williams, Torin Thatcher, Norma Varden, Una O’Connor | US Crime Drama | 116′ Dir: Lance Comfort | Cast: Simone Simon, Robert Newton, William Hartnell, Margaret Barton | Noir Thriller | UK |

Dir: Lance Comfort | Cast: Simone Simon, Robert Newton, William Hartnell, Margaret Barton | Noir Thriller | UK | The Closing Night will be the UK Premiere of

The Closing Night will be the UK Premiere of  There will be two retrospectives in honour of non-fiction filmmaking: The innovative found footage documentarian Penny Lane and Japanese pioneer of ‘action documentary’, Kazuo Hara. Both filmmakers will be at the festival to present their work.

There will be two retrospectives in honour of non-fiction filmmaking: The innovative found footage documentarian Penny Lane and Japanese pioneer of ‘action documentary’, Kazuo Hara. Both filmmakers will be at the festival to present their work. Open City Documentary Festival is looking forward to hosting a number of exciting festival parties this year including the Opening and Closing Night Receptions at the Regent Street Cinema as well as the Nabihah Iqbal after-party at the ICA, where the DJ, Producer & NTS Radio presenter presents an evening of music inspired by 1972 documentary Winter Soldier, featuring protest songs and music from the anti-war movement from 1950-1975. Other various festival parties will be listed in the festival programme.

Open City Documentary Festival is looking forward to hosting a number of exciting festival parties this year including the Opening and Closing Night Receptions at the Regent Street Cinema as well as the Nabihah Iqbal after-party at the ICA, where the DJ, Producer & NTS Radio presenter presents an evening of music inspired by 1972 documentary Winter Soldier, featuring protest songs and music from the anti-war movement from 1950-1975. Other various festival parties will be listed in the festival programme. THE MICHAEL POWELL AWARD FOR BEST BRITISH FEATURE FILM

THE MICHAEL POWELL AWARD FOR BEST BRITISH FEATURE FILM THE AWARD FOR BEST PERFORMANCE IN A BRITISH FEATURE FILM

THE AWARD FOR BEST PERFORMANCE IN A BRITISH FEATURE FILM THE AWARD FOR BEST INTERNATIONAL FEATURE FILM

THE AWARD FOR BEST INTERNATIONAL FEATURE FILM THE AWARD FOR BEST DOCUMENTARY FEATURE FILM

THE AWARD FOR BEST DOCUMENTARY FEATURE FILM Dir: Paul Van Carter | Doc | UK |

Dir: Paul Van Carter | Doc | UK | Woodfall Film Productions was founded in 1958 by English director Tony Richardson (1928-1991), the American producer Harry Saltzman (later of James Bond fame) and the English author and playwright John Osborne, whose play Look back in Anger was filmed by Richardson in 1959 as the opus number of the company that championed the British New Wave. So it’s only fitting that Richardson should finish the circle in 1984 with Hotel New Hampshire, creating a sub-genre of dram-com, which was later developed by Wes Anderson.

Woodfall Film Productions was founded in 1958 by English director Tony Richardson (1928-1991), the American producer Harry Saltzman (later of James Bond fame) and the English author and playwright John Osborne, whose play Look back in Anger was filmed by Richardson in 1959 as the opus number of the company that championed the British New Wave. So it’s only fitting that Richardson should finish the circle in 1984 with Hotel New Hampshire, creating a sub-genre of dram-com, which was later developed by Wes Anderson. The Entertainer featured Laurence Olivier in the title role, reprising his stage role from the Royal Court, co-written by John Osborne from his own play. There is nothing heroic about Olivier’s Archie Rice: he is a bankrupt womaniser, exploiting his long suffering wife Phoebe (de Banzie) and using Tina Lapford (Field) – who came second in the Miss Britain contest – and her wealthy family to prolong his stage career. Not even the death of his son in the Suez conflict can deter him from his vain pursuit of a long dead career. Using his father – who dies on stage – for his own advantage, Archie sinks deeper and deeper. There is a poignant scene with his film daughter Jean (Plowright), whom he asks: “What would think, if I married a woman your age?” and Jean answers exasperated “Oh. Daddy”. At the end of productions, Olivier would marry Plowright, after his divorce from Vivien Leigh. Shot partly at Margate, this is a bleak portrait of show business, shot in brilliant black and white by the great Oswald Morris (Moby Dick, A Farewell to Arms).

The Entertainer featured Laurence Olivier in the title role, reprising his stage role from the Royal Court, co-written by John Osborne from his own play. There is nothing heroic about Olivier’s Archie Rice: he is a bankrupt womaniser, exploiting his long suffering wife Phoebe (de Banzie) and using Tina Lapford (Field) – who came second in the Miss Britain contest – and her wealthy family to prolong his stage career. Not even the death of his son in the Suez conflict can deter him from his vain pursuit of a long dead career. Using his father – who dies on stage – for his own advantage, Archie sinks deeper and deeper. There is a poignant scene with his film daughter Jean (Plowright), whom he asks: “What would think, if I married a woman your age?” and Jean answers exasperated “Oh. Daddy”. At the end of productions, Olivier would marry Plowright, after his divorce from Vivien Leigh. Shot partly at Margate, this is a bleak portrait of show business, shot in brilliant black and white by the great Oswald Morris (Moby Dick, A Farewell to Arms).  Set in a desolate Manchester, A Taste of Honey would make a star of the lead actor Rita Tushingham. She plays 17-year old school girl Jo, who is totally neglected by her sex-mad mother Helen (Bryan), who only has time for her fiancée Robert (Stephens). Jo gets pregnant by the black sailor Jimmy (Danquah), who soon leaves with his ship. Jo befriends the textile student Geoffrey, a brilliant Murray Melvin, who is not sure about his sexual orientation. He looks lovingly after her, before Helen returns, after having been rejected by Robert. She shucks Geoffrey out, and pretends to look after her daughter and the baby, whilst having one eye on the next, potential suitor. A Taste of Honey is relentlessly gloomy and discouraging. Photographed innovatively

Set in a desolate Manchester, A Taste of Honey would make a star of the lead actor Rita Tushingham. She plays 17-year old school girl Jo, who is totally neglected by her sex-mad mother Helen (Bryan), who only has time for her fiancée Robert (Stephens). Jo gets pregnant by the black sailor Jimmy (Danquah), who soon leaves with his ship. Jo befriends the textile student Geoffrey, a brilliant Murray Melvin, who is not sure about his sexual orientation. He looks lovingly after her, before Helen returns, after having been rejected by Robert. She shucks Geoffrey out, and pretends to look after her daughter and the baby, whilst having one eye on the next, potential suitor. A Taste of Honey is relentlessly gloomy and discouraging. Photographed innovatively Nothing could be more different than Richardson’s next project, the historical romp Tom Jones, based on the novel by Henry Fielding. Albert Finney is the bumptious titular hero, who is nearly hanged due to the schemes by his adversary Bliflil (the debut for David Warner). With a great love story involving Sophie Western (York) and her father (Griffith), there are some great performances by Edith Evans, Joan Greenwood and Diane Cilento. Like his auteur Richardson, Lassally changes style effortlessly in this colourful wide-screen bonanza. It would garner an Oscar for Richardson, and was a huge success at the box office: the slender budget of £467000 pounds would result in a cool 70 million takings. AS

Nothing could be more different than Richardson’s next project, the historical romp Tom Jones, based on the novel by Henry Fielding. Albert Finney is the bumptious titular hero, who is nearly hanged due to the schemes by his adversary Bliflil (the debut for David Warner). With a great love story involving Sophie Western (York) and her father (Griffith), there are some great performances by Edith Evans, Joan Greenwood and Diane Cilento. Like his auteur Richardson, Lassally changes style effortlessly in this colourful wide-screen bonanza. It would garner an Oscar for Richardson, and was a huge success at the box office: the slender budget of £467000 pounds would result in a cool 70 million takings. AS An Evening With Beverly Luff Linn (Director: Jim Hosking,

An Evening With Beverly Luff Linn (Director: Jim Hosking, Eighth Grade (Director/Screenwriter: Bo Burnham) – Thirteen-year-old Kayla endures the tidal wave of contemporary suburban adolescence as she makes her way through the last week of middle school — the end of her thus far disastrous eighth grade year — before she begins high school.

Eighth Grade (Director/Screenwriter: Bo Burnham) – Thirteen-year-old Kayla endures the tidal wave of contemporary suburban adolescence as she makes her way through the last week of middle school — the end of her thus far disastrous eighth grade year — before she begins high school. Generation Wealth (Director: Lauren Greenfield) – Lauren Greenfield’s postcard from the edge of the American Empire captures a portrait of a materialistic, image-obsessed culture. Simultaneously personal journey and historical essay, the film bears witness to the global boom–bust economy, the corrupted American Dream and the human costs of late stage capitalism, narcissism and greed.

Generation Wealth (Director: Lauren Greenfield) – Lauren Greenfield’s postcard from the edge of the American Empire captures a portrait of a materialistic, image-obsessed culture. Simultaneously personal journey and historical essay, the film bears witness to the global boom–bust economy, the corrupted American Dream and the human costs of late stage capitalism, narcissism and greed. Half the Picture (Director: Amy Adrion) – At a pivotal moment for gender equality in Hollywood, successful women directors tell the stories of their art, lives and careers. Having endured a long history of systemic discrimination, women filmmakers may be getting the first glimpse of a future that values their voices equally.

Half the Picture (Director: Amy Adrion) – At a pivotal moment for gender equality in Hollywood, successful women directors tell the stories of their art, lives and careers. Having endured a long history of systemic discrimination, women filmmakers may be getting the first glimpse of a future that values their voices equally. Hereditary (Director/Screenwriter: Ari Aster) – After their reclusive grandmother passes away, the Graham family tries to escape the dark fate they’ve inherited.

Hereditary (Director/Screenwriter: Ari Aster) – After their reclusive grandmother passes away, the Graham family tries to escape the dark fate they’ve inherited. Leave No Trace (Director: Debra Granik, Screenwriters: Debra Granik, Anne Rosellini) – A father and daughter live a perfect but mysterious existence in Forest Park, a beautiful nature reserve near Portland, Oregon, rarely making contact with the world. A small mistake tips them off to authorities sending them on an increasingly erratic journey in search of a place to call their own.

Leave No Trace (Director: Debra Granik, Screenwriters: Debra Granik, Anne Rosellini) – A father and daughter live a perfect but mysterious existence in Forest Park, a beautiful nature reserve near Portland, Oregon, rarely making contact with the world. A small mistake tips them off to authorities sending them on an increasingly erratic journey in search of a place to call their own. The Miseducation of Cameron Post (Director: Desiree Akhavan, Screenwriters: Desiree Akhavan, Cecilia Frugiuele) –1993: after being caught having sex with the prom queen, a girl is forced into a gay conversion therapy center. Based on Emily Danforth’s acclaimed and controversial coming-of-age novel.

The Miseducation of Cameron Post (Director: Desiree Akhavan, Screenwriters: Desiree Akhavan, Cecilia Frugiuele) –1993: after being caught having sex with the prom queen, a girl is forced into a gay conversion therapy center. Based on Emily Danforth’s acclaimed and controversial coming-of-age novel. Never Goin’ Back (Director/Screenwriter: Augustine Frizzell) –Jessie and Angela, high school dropout BFFs, are taking a week off to chill at the beach. Too bad their house got robbed, rent’s due, they’re about to get fired and they’re broke. Now they’ve gotta avoid eviction, stay out of jail and get to the beach, no matter what!!!

Never Goin’ Back (Director/Screenwriter: Augustine Frizzell) –Jessie and Angela, high school dropout BFFs, are taking a week off to chill at the beach. Too bad their house got robbed, rent’s due, they’re about to get fired and they’re broke. Now they’ve gotta avoid eviction, stay out of jail and get to the beach, no matter what!!! Skate Kitchen (Director: Crystal Moselle, Screenwriters: Crystal Moselle, Ashlihan Unaldi) – Camille’s life as a lonely suburban teenager changes dramatically when she befriends a group of girl skateboarders. As she journeys deeper into this raw New York City subculture, she begins to understand the true meaning of friendship as well as her inner self.

Skate Kitchen (Director: Crystal Moselle, Screenwriters: Crystal Moselle, Ashlihan Unaldi) – Camille’s life as a lonely suburban teenager changes dramatically when she befriends a group of girl skateboarders. As she journeys deeper into this raw New York City subculture, she begins to understand the true meaning of friendship as well as her inner self. The Tale (Director/Screenwriter: Jennifer Fox) – An investigation into one woman’s memory as she’s forced to re-examine her first sexual relationship and the stories we tell ourselves in order to survive; based on the filmmaker’s own story.

The Tale (Director/Screenwriter: Jennifer Fox) – An investigation into one woman’s memory as she’s forced to re-examine her first sexual relationship and the stories we tell ourselves in order to survive; based on the filmmaker’s own story. Yardie (Director: Idris Elba, Screenwriters: Brock Norman Brock, Martin Stellman) – Jamaica, 1973. When a young boy witnesses his brother’s assassination, a powerful Don gives him a home. Ten years later he is sent on a mission to London. He reunites with his girlfriend and their daughter, but then the past catches up with them. Based on Victor Headley’s novel.

Yardie (Director: Idris Elba, Screenwriters: Brock Norman Brock, Martin Stellman) – Jamaica, 1973. When a young boy witnesses his brother’s assassination, a powerful Don gives him a home. Ten years later he is sent on a mission to London. He reunites with his girlfriend and their daughter, but then the past catches up with them. Based on Victor Headley’s novel. Dir.: Jamie Jones; Cast: Marcus Rutherford, Sophie Kennedy Clark, T’Nia Miller, James Atwell, Sam Gittins; UK 2018, 93 min.

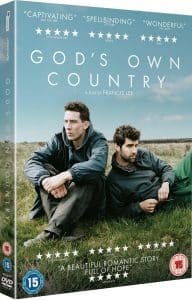

Dir.: Jamie Jones; Cast: Marcus Rutherford, Sophie Kennedy Clark, T’Nia Miller, James Atwell, Sam Gittins; UK 2018, 93 min. London is the setting for the UK’s longest running LGBTQ film event which began in 1986 as Gay’s Own Pictures. Since then it has also become the largest LGBTQ film event in the UK with this year’s edition boasting 56 feature films, an expanded industry programme, selected films on BFI Player VOD service, and a series of special events and archive screenings. With its partner fiveFilms4freedom it offers LGBT short films for free across the world and promoted through the British Council’s global networks.

London is the setting for the UK’s longest running LGBTQ film event which began in 1986 as Gay’s Own Pictures. Since then it has also become the largest LGBTQ film event in the UK with this year’s edition boasting 56 feature films, an expanded industry programme, selected films on BFI Player VOD service, and a series of special events and archive screenings. With its partner fiveFilms4freedom it offers LGBT short films for free across the world and promoted through the British Council’s global networks. Opening the festival this year is Talit Shalom-Ezer’s poignant lesbian love story MY DAYS OF MERCY written by Joe Barton, who scripted TV’s Troy, and featuring Kate Mara and Ellen Page. The European premiere of moral fable POSTCARDS FROM LONDON is the closing gala, telling a revealing story of a suburban teenager (Harris Dickinson) arriving in the West End where he falls in with a gang of high class male escorts ‘The Raconteurs’. Set in a vibrant, neon-lit, imaginary vision of Soho, the film works as a beautifully shot homage to the spirit of Derek Jarman and a celebration of the homo-erotic in Baroque art, and is Steve McLean’s long-awaited follow-up to his 1994 Sundance and Indie Spirit-nominated drama POSTCARDS FROM AMERICA. This year ‘Second Chance Sunday offers the opportunity to watch the on-demand repeat screenings of the audience festival favourites.

Opening the festival this year is Talit Shalom-Ezer’s poignant lesbian love story MY DAYS OF MERCY written by Joe Barton, who scripted TV’s Troy, and featuring Kate Mara and Ellen Page. The European premiere of moral fable POSTCARDS FROM LONDON is the closing gala, telling a revealing story of a suburban teenager (Harris Dickinson) arriving in the West End where he falls in with a gang of high class male escorts ‘The Raconteurs’. Set in a vibrant, neon-lit, imaginary vision of Soho, the film works as a beautifully shot homage to the spirit of Derek Jarman and a celebration of the homo-erotic in Baroque art, and is Steve McLean’s long-awaited follow-up to his 1994 Sundance and Indie Spirit-nominated drama POSTCARDS FROM AMERICA. This year ‘Second Chance Sunday offers the opportunity to watch the on-demand repeat screenings of the audience festival favourites. Other films to look out for are Rupert Everett’s Oscar Wilde-themed passion project THE HAPPY PRINCE in which he also stars alongside Colin Firth and Emily Watson. Robin Campillo’s rousing celebration of AIDS activism 120 BPM. MAURICE, a sumptuous restoration of the 1987 adaptation of E M Forster’s gay novel starring James Wilby and Rupert Graves.

Other films to look out for are Rupert Everett’s Oscar Wilde-themed passion project THE HAPPY PRINCE in which he also stars alongside Colin Firth and Emily Watson. Robin Campillo’s rousing celebration of AIDS activism 120 BPM. MAURICE, a sumptuous restoration of the 1987 adaptation of E M Forster’s gay novel starring James Wilby and Rupert Graves.  Avant-garde Berlinale Teddy feature HARD PAINT presents a startlingly cinematic look at how a college drop-out deals with his needs, and Locarno favourite, a saucy Sao Paolo-set vampire drama

Avant-garde Berlinale Teddy feature HARD PAINT presents a startlingly cinematic look at how a college drop-out deals with his needs, and Locarno favourite, a saucy Sao Paolo-set vampire drama  The Crowhurst story has spawned various theatrical and literary adaptations, and even a chamber opera: The Strange Last Voyage of Donald Crowhurst. Eric Colvin plays him in Simon Rumley’s upcoming low budget indie thriller Crowhurst which purportedly features the actual vessel that set sail in the endeavour.

The Crowhurst story has spawned various theatrical and literary adaptations, and even a chamber opera: The Strange Last Voyage of Donald Crowhurst. Eric Colvin plays him in Simon Rumley’s upcoming low budget indie thriller Crowhurst which purportedly features the actual vessel that set sail in the endeavour. Firth is brilliantly cast as Crowhurst – blending just the right amount of pathos and self-belief in his portrait of an unsatisfactory businessman of a rather nervous disposition who can’t take pressure and lacks personal conviction (possibly due to his mother dressing him as a much wanted girl until the age of 17). His marriage is clearly happy and Rachel Weisz plays his wife as a typically supportive English rose, stalwart in her affections and a brilliant mum but rather passive and naive in a commercial sense, as most women were in the those days.

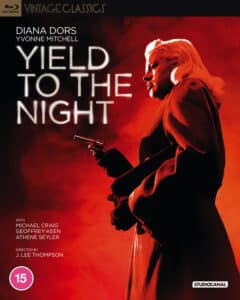

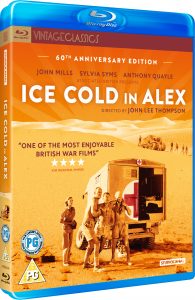

Firth is brilliantly cast as Crowhurst – blending just the right amount of pathos and self-belief in his portrait of an unsatisfactory businessman of a rather nervous disposition who can’t take pressure and lacks personal conviction (possibly due to his mother dressing him as a much wanted girl until the age of 17). His marriage is clearly happy and Rachel Weisz plays his wife as a typically supportive English rose, stalwart in her affections and a brilliant mum but rather passive and naive in a commercial sense, as most women were in the those days. Dir: J Lee Thompson | Cast: John Mills, Sylvia Syms, Anthony Quayle | UK | 122’

Dir: J Lee Thompson | Cast: John Mills, Sylvia Syms, Anthony Quayle | UK | 122’

FOREIGN-LANGUAGE FILM OF THE YEAR (left)

FOREIGN-LANGUAGE FILM OF THE YEAR (left) ACTOR OF THE YEAR

ACTOR OF THE YEAR YOUNG BRITISH/IRISH PERFORMER OF THE YEAR

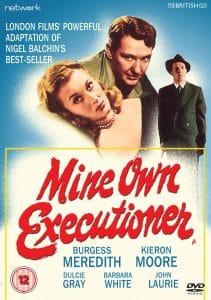

YOUNG BRITISH/IRISH PERFORMER OF THE YEAR Dir: Anthony Kimmins | Writer: Nigel Balchin | Psychological Drama | UK | Burgess Meredith, Barbara White, Kieron Moore, Dulcie Gray

Dir: Anthony Kimmins | Writer: Nigel Balchin | Psychological Drama | UK | Burgess Meredith, Barbara White, Kieron Moore, Dulcie Gray US DRAMA –

US DRAMA – Filmmaker Maren Ade has created one of the most poignant and refreshingly humorous German arthouse comedy dramas of recent memory – it never drags despite its three-hour running time. Picturing the absurd and often awkward nature of family relationships, this is a life-affirming experience not to be missed, especially at Christmas time. After The Forest for the Trees and Everyone Else, Ade is working her way slowly but surely to the top as most of the most refreshing European writer directors around..

Filmmaker Maren Ade has created one of the most poignant and refreshingly humorous German arthouse comedy dramas of recent memory – it never drags despite its three-hour running time. Picturing the absurd and often awkward nature of family relationships, this is a life-affirming experience not to be missed, especially at Christmas time. After The Forest for the Trees and Everyone Else, Ade is working her way slowly but surely to the top as most of the most refreshing European writer directors around.. There’s something sad and awkwardly compulsive about this cautionary tale of a misguided intergenerational liaison between a lonely man and a glib young woman who meet in an island paradise. One of the best recent dramas about delusional love and its grim aftermath that perfectly epitomises the sinking realisation of being ‘over the hill’ on a holiday fling, while still holding on to the dream . Slim and but beautifully scenic and deeply resonant in its evergreen theme.

There’s something sad and awkwardly compulsive about this cautionary tale of a misguided intergenerational liaison between a lonely man and a glib young woman who meet in an island paradise. One of the best recent dramas about delusional love and its grim aftermath that perfectly epitomises the sinking realisation of being ‘over the hill’ on a holiday fling, while still holding on to the dream . Slim and but beautifully scenic and deeply resonant in its evergreen theme. THRILLER –

THRILLER –  UK DEBUT –

UK DEBUT –  UK COMEDY –

UK COMEDY –

Hopkins’ fraud of a film is full of middle-aged cyphers floating around in a fantasy world of the Seventies where they meet for coffee mornings and discuss worthy causes. But in the real place, this lot passed on decades ago to be replaced by the likes of Hugh Skinner’s fundraising nerd or the smiling Romanians touting The Big Issue at every street corner. Robert Festinger’s script teeters from crass to cringeworthy with no laughs to be had, and a score that jars. Hampstead is utterly specious and hollow – even Diane Keaton can’t save it.

Hopkins’ fraud of a film is full of middle-aged cyphers floating around in a fantasy world of the Seventies where they meet for coffee mornings and discuss worthy causes. But in the real place, this lot passed on decades ago to be replaced by the likes of Hugh Skinner’s fundraising nerd or the smiling Romanians touting The Big Issue at every street corner. Robert Festinger’s script teeters from crass to cringeworthy with no laughs to be had, and a score that jars. Hampstead is utterly specious and hollow – even Diane Keaton can’t save it. A fantastic box set that brings together dazzling high def print of some of the best films in the crime genre: THE DARK MIRROR (1946) starring Olivia de Havilland; Fritz Lang’s SECRET BEYOND THE DOOR (1947) with Joan Bennett and Michael Redgrave; FORCE OF EVIL (1948) directed by the underrated Abraham Polonsky; and Cornel Joseph H Lewis’ THE BIG COMBO (1955); with its terrific score by David Raksin with dynamite duo Cornel Wilde and Jean Wallace. The dual format edition comes with a hardback book on the films. MT

A fantastic box set that brings together dazzling high def print of some of the best films in the crime genre: THE DARK MIRROR (1946) starring Olivia de Havilland; Fritz Lang’s SECRET BEYOND THE DOOR (1947) with Joan Bennett and Michael Redgrave; FORCE OF EVIL (1948) directed by the underrated Abraham Polonsky; and Cornel Joseph H Lewis’ THE BIG COMBO (1955); with its terrific score by David Raksin with dynamite duo Cornel Wilde and Jean Wallace. The dual format edition comes with a hardback book on the films. MT