SUNDANCE is the first major film festival of the year; a true indie festival coming to you from snowy Utah courtesy of its founder Robert Redford. Setting the benchmark for independent titles in 2015, SUNDANCE focuses on excellence in screenplays and innovativeness in cinematography: each filmmaker is put their paces before their film can be considered in competition. Unlike the Academy Awards, SUNDANCE is purely about talent. We have highlighted the buzzworthy titles in RED and winners – watch out for them!

BEST FILMS

Grand Jury Prize: Dramatic – Me & Earl & the Dying Girl by Alfonso Gomez-Rejon

Grand Jury Prize: Documentary – The Wolfpack by Crystal Moselle

World Cinema Jury Prize: Dramatic – Slow West by John Maclean

World Cinema Jury Prize: Documentary – The Russian Woodpecker by Chad Gracia

Special Jury Prize for Breakout First Feature: Documentary – Lyric R. Cabral and David Felix Sutcliffe for (T)error

BEST DIRECTORS

Directing Award: Dramatic – Robert Eggers for The Witch

Directing Award: Documentary – Matthew Heineman for Cartel Land

World Cinema Directing Award: Dramatic – Alanté Kavaïté for The Summer of Sangailé

World Cinema Directing Award: Documentary – Kim Longinotto for Dreamcatcher

BEST SCRIPTS, CINEMATOGRAPHY and ACTING

Best Script: Waldo Salt Screenwriting Award – Tim Talbott for The Stanford Prison Experiment

Cinematography Award: Documentary – Matthew Heineman and Matt Porwoll for Cartel Land

Cinematography Award: Drama – Partisan

World Cinema Special Jury Prize for Acting: Dramatic – Regina Casé and Camila Márdila for The Second Mother

World Cinema Special Jury Prize for Acting: Dramatic – Jack Reynor for Glassland

AUDIENCE AWARDS

World Cinema Audience Award: Dramatic – Umrika by Prashant Nair

World Cinema Audience Award: Documentary – Dark Horse by Louise Osmond

Audience Award: Documentary – Meru by Jimmy Chin and Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi

Audience Award: Dramatic – Me & Earl & the Dying Girl by Alfonso Gomez-Rejon

Best of NEXT Audience Award – James White by Josh Mond

U .S. D R A M A T I C C O M P E T I T I O N

ADVANTAGEOUS / U.S.A. (Director: Jennifer Phang, Screenwriters: Jacqueline Kim, Jennifer Phang) — In a near-future city where soaring opulence overshadows economic hardship, Gwen and her daughter, Jules, do all they can to hold on to their joy, despite the instability surfacing in their world. Cast: Jacqueline Kim, James Urbaniak, Freya Adams, Ken Jeong, Jennifer Ehle, Samantha Kim.

ADVANTAGEOUS / U.S.A. (Director: Jennifer Phang, Screenwriters: Jacqueline Kim, Jennifer Phang) — In a near-future city where soaring opulence overshadows economic hardship, Gwen and her daughter, Jules, do all they can to hold on to their joy, despite the instability surfacing in their world. Cast: Jacqueline Kim, James Urbaniak, Freya Adams, Ken Jeong, Jennifer Ehle, Samantha Kim.

THE BRONZE / U.S.A. (Director: Bryan Buckley, Screenwriters: Melissa Rauch, Winston Rauch) — In 2004, Hope Ann Greggory became an American hero after winning the bronze medal for the women’s gymnastics team. Today, she’s still living in her small hometown, washed-up and embittered. Stuck in the past, Hope must reassess her life when a promising young gymnast threatens her local celebrity status. Cast: Melissa Rauch, Gary Cole, Thomas Middleditch, Sebastian Stan, Haley Lu Richardson, Cecily Strong.

THE BRONZE / U.S.A. (Director: Bryan Buckley, Screenwriters: Melissa Rauch, Winston Rauch) — In 2004, Hope Ann Greggory became an American hero after winning the bronze medal for the women’s gymnastics team. Today, she’s still living in her small hometown, washed-up and embittered. Stuck in the past, Hope must reassess her life when a promising young gymnast threatens her local celebrity status. Cast: Melissa Rauch, Gary Cole, Thomas Middleditch, Sebastian Stan, Haley Lu Richardson, Cecily Strong.

THE D TRAIN / U.S.A. (Directors and screenwriters: Jarrad Paul, Andrew Mogel) — With his 20th reunion looming, Dan can’t shake his high school insecurities. In a misguided mission to prove he’s changed, Dan rekindles a friendship with the popular guy from his class and is left scrambling to protect more than just his reputation when a wild night takes an unexpected turn. Cast: Jack Black, James Marsden, Kathryn Hahn, Jeffrey Tambor, Mike White, Kyle Bornheimer.

THE D TRAIN / U.S.A. (Directors and screenwriters: Jarrad Paul, Andrew Mogel) — With his 20th reunion looming, Dan can’t shake his high school insecurities. In a misguided mission to prove he’s changed, Dan rekindles a friendship with the popular guy from his class and is left scrambling to protect more than just his reputation when a wild night takes an unexpected turn. Cast: Jack Black, James Marsden, Kathryn Hahn, Jeffrey Tambor, Mike White, Kyle Bornheimer.

THE DIARY OF A TEENAGE GIRL / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Marielle Heller) — Minnie Goetze is a 15-year-old aspiring comic-book artist, coming of age in the haze of the 1970s in San Francisco. Insatiably curious about the world around her, Minnie is a pretty typical teenage girl. Oh, except that she’s sleeping with her mother’s boyfriend. Cast: Bel Powley, Alexander Skarsgård, Christopher Meloni, Kristen Wiig.

THE DIARY OF A TEENAGE GIRL / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Marielle Heller) — Minnie Goetze is a 15-year-old aspiring comic-book artist, coming of age in the haze of the 1970s in San Francisco. Insatiably curious about the world around her, Minnie is a pretty typical teenage girl. Oh, except that she’s sleeping with her mother’s boyfriend. Cast: Bel Powley, Alexander Skarsgård, Christopher Meloni, Kristen Wiig.

DOPE/ U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Rick Famuyiwa) — Malcolm is carefully surviving life in a tough neighborhood in Los Angeles while juggling college applications, academic interviews, and the SAT. A chance invitation to an underground party leads him into an adventure that could allow him to go from being a geek, to being dope, to ultimately being himself. Cast: Shameik Moore, Tony Revolori, Kiersey Clemons, Blake Anderson, Zoë Kravitz, A$AP Rocky.

I SMILE BACK / U.S.A. (Director: Adam Salky, Screenwriters: Amy Koppelman, Paige Dylan) —Laney Brooks does bad things. Married with kids, she takes the drugs she wants, sleeps with the men she wants, disappears when she wants. Now, with the destruction of her family looming, and temptation everywhere, Laney makes one last desperate attempt at redemption. Cast: Sarah Silverman, Josh Charles, Thomas Sadoski, Mia Barron, Terry Kinney, Chris Sarandon.

I SMILE BACK / U.S.A. (Director: Adam Salky, Screenwriters: Amy Koppelman, Paige Dylan) —Laney Brooks does bad things. Married with kids, she takes the drugs she wants, sleeps with the men she wants, disappears when she wants. Now, with the destruction of her family looming, and temptation everywhere, Laney makes one last desperate attempt at redemption. Cast: Sarah Silverman, Josh Charles, Thomas Sadoski, Mia Barron, Terry Kinney, Chris Sarandon.

Me and Earl and the Dying Girl / U.S.A. (Director: Alfonso Gomez-Rejon, Screenwriter: Jesse Andrews) is getting some great reviews, judging by the buzz currently coming out the festival crowd. Greg is coasting through senior year of high school as anonymously as possible, avoiding social interactions like the plague while secretly making spirited, bizarre films with Earl, his only friend. But both his anonymity and friendship threaten to unravel when his mother forces him to befriend a classmate with leukemia. Cast: Thomas Mann, RJ Cyler, Olivia Cooke, Nick Offerman, Connie Britton, Molly Shannon. WINTER : Audience Award: Dramatic

THE OVERNIGHT / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Patrick Brice) — In an attempt to acclimate to Los Angeles, a young couple spends an increasingly bizarre evening with the parents of their son’s new friend. Cast: Adam Scott, Taylor Schilling, Jason Schwartzman, Judith Godrèche.

PEOPLE, PLACES, THINGS/ U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: James C. Strouse) — Will Henry is a newly single graphic novelist balancing being a parent to his young twin daughters and teaching a classroom full of college students, all the while trying to navigate the rich complexities of new love and letting go of the woman who left him. Cast: Jemaine Clement, Regina Hall, Stephanie Allynne, Jessica Williams, Gia Gadsby, Aundrea Gadsby.

RESULTS / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Andrew Bujalski) — Two mismatched personal trainers’ lives are upended by the actions of a new, wealthy client. Cast: Guy Pearce, Cobie Smulders, Kevin Corrigan, Giovanni Ribisi, Anthony Michael Hall, Brooklyn Decker.

SONGS MY BROTHERS TAUGHT ME / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Chloé Zhao) — This complex portrait of modern-day life on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation explores the bond between a brother and his younger sister, who find themselves on separate paths to rediscovering the meaning of home. Cast: John Reddy, Jashaun St. John, Irene Bedard, Taysha Fuller, Travis Lone Hill, Eléonore Hendricks.

THE STANFORD PRISON EXPERIMENT / U.S.A. (Director: Kyle Patrick Alvarez, Screenwriter: Tim Talbott) — Based on the actual events that took place in 1971, when Stanford professor Dr. Philip Zimbardo created what became one of the most shocking and famous social experiments of all time. Cast: Billy Crudup, Ezra Miller, Michael Angarano, Tye Sheridan, Johnny Simmons, Olivia Thirlby. BEST SCRIPT

STOCKHOLM, PENNSYLVANIA/ U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Nikole Beckwith) — A young woman is returned home to her biological parents after living with her abductor for 17 years. Cast: Saoirse Ronan, Cynthia Nixon, Jason Isaacs, David Warshofsky.

UNEXPECTED / U.S.A. (Director: Kris Swanberg, Screenwriters: Kris Swanberg, Megan Mercier) — When Samantha Abbott begins her final semester teaching science at a Chicago high school, she faces some unexpected news: she’s pregnant. Soon after, Samantha learns that one of her favorite students, Jasmine, has landed in a similar situation. Unexpected follows the two women as they embark on an unlikely friendship. Cast: Cobie Smulders, Anders Holm, Gail Bean, Elizabeth McGovern.

THE WITCH/ U.S.A., Canada (Director and screenwriter: Robert Eggers) — Another buzzworthy title at this year’s festival is set in New England in the 1630s: William and Katherine lead a devout Christian life with five children, homesteading on the edge of an impassable wilderness. When their newborn son vanishes and crops fail, the family turns on one another. Beyond their worst fears, a supernatural evil lurks in the nearby wood. Cast: Anya Taylor Joy, Ralph Ineson, Kate Dickie, Harvey Scrimshaw, Lucas Dawson, Ellie Grainger.

Z FOR ZACHARIAH / U.S.A. (Director: Craig Zobel, Screenwriter: Nissar Modi) — In a post-apocalyptic world, a young woman who believes she is the last human on Earth meets a dying scientist searching for survivors. Their relationship becomes tenuous when another survivor appears. As the two men compete for the woman’s affection, their primal urges begin to reveal their true nature. Cast: Chiwetel Ejiofor, Margot Robbie, Chris Pine.

U .S. D O C U M E N T A R Y C O M P E T I T I O N

U .S. D O C U M E N T A R Y C O M P E T I T I O N

Sixteen world-premiere American documentaries that illuminate the ideas, people, and events that shape the present day.

3½ MINUTES / U.S.A. (Director: Marc Silver) — On November 23, 2012, unarmed 17-year-old Jordan Russell Davis was shot at a Jacksonville gas station by Michael David Dunn. 3½ MINUTES explores the aftermath of Jordan’s tragic death, the latent and often unseen effects of racism, and the contradictions of the American criminal justice system.

BEING EVIL / U.S.A. (Director: Daniel Junge) —Millions know the man, but few know his story. Academy Award-winner Daniel Junge (Saving Face) and actor/producer Johnny Knoxville reveal an unprecedented and candid look at American daredevil and icon Robert “Evel” Knievel. Being Evel is a surprising tale about a childhood hero…flaws and all.

BEST OF ENEMIES U.S.A. (Directors: Morgan Neville, Robert Gordon) — Best of Enemies is a behind-the-scenes account of the explosive 1968 televised debates between the liberal Gore Vidal and the conservative William F. Buckley Jr., and their rancorous disagreements about politics, God, and sex.

CALL ME LUCKY / U.S.A. (Director: Bobcat Goldthwait) — Barry Crimmins was a volatile but brilliant bar comic who became an honored peace activist and influential political satirist. Famous comedians and others build a picture of a man who underwent an incredible transformation.

CALL ME LUCKY / U.S.A. (Director: Bobcat Goldthwait) — Barry Crimmins was a volatile but brilliant bar comic who became an honored peace activist and influential political satirist. Famous comedians and others build a picture of a man who underwent an incredible transformation.

CARTEL LAND/ U.S.A., Mexico (Director: Matthew Heineman) — In this classic Western set in the 21st century, vigilantes on both sides of the border fight the vicious Mexican drug cartels. With unprecedented access, this character-driven film provokes deep questions about lawlessness, the breakdown of order, and whether citizens should fight violence with violence. Directing Award: Documentary

CITY OF GOLD/ U.S.A. (Director: Laura Gabbert) — Pulitzer Prize-winning critic Jonathan Gold casts his light upon a vibrant and growing cultural movement in which he plays the dual roles of high-low priest and culinary geographer of his beloved Los Angeles.

CITY OF GOLD/ U.S.A. (Director: Laura Gabbert) — Pulitzer Prize-winning critic Jonathan Gold casts his light upon a vibrant and growing cultural movement in which he plays the dual roles of high-low priest and culinary geographer of his beloved Los Angeles.

FINDERS KEEPERS / U.S.A. (Directors: Bryan Carberry, Clay Tweel) — Recovering addict and amputee John Wood finds himself in a stranger-than-fiction battle to reclaim his mummified leg from Southern entrepreneur Shannon Whisnant, who found it in a grill he bought at an auction and believes it to therefore be his rightful property.

HOT GIRLS WANTED / U.S.A. (Directors: Jill Bauer, Ronna Gradus) — Hot Girls Wanted is a first-ever look at the realities inside the world of the amateur porn industry and the steady stream of 18- and 19-year-old girls entering into it.

HOW TO DANCE IN OHIO / U.S.A. (Director: Alexandra Shiva) — In Columbus, Ohio, a group of teenagers and young adults on the autism spectrum prepare for an iconic American rite of passage — a spring formal. They spend 12 weeks practicing their social skills in preparation for the dance at a local nightclub.

HOW TO DANCE IN OHIO / U.S.A. (Director: Alexandra Shiva) — In Columbus, Ohio, a group of teenagers and young adults on the autism spectrum prepare for an iconic American rite of passage — a spring formal. They spend 12 weeks practicing their social skills in preparation for the dance at a local nightclub.

LARRY KRAMER IN LOVE AND ANGER / U.S.A. (Director: Jean Carlomusto) — Author, activist, and playwright Larry Kramer is one of the most important and controversial figures in contemporary gay America, a political firebrand who gave voice to the outrage and grief that inspired gay men and lesbians to fight for their lives. At 78, this complicated man still commands our attention.

MERU / U.S.A. (Directors: Jimmy Chin, E. Chai Vasarhelyi) — Three elite mountain climbers sacrifice everything but their friendship as they struggle through heartbreaking loss and nature’s harshest elements to attempt the never-before-completed Shark’s Fin on Mount Meru, the most coveted first ascent in the dangerous game of Himalayan big wall climbing. Audience Award: Dramatic

MERU / U.S.A. (Directors: Jimmy Chin, E. Chai Vasarhelyi) — Three elite mountain climbers sacrifice everything but their friendship as they struggle through heartbreaking loss and nature’s harshest elements to attempt the never-before-completed Shark’s Fin on Mount Meru, the most coveted first ascent in the dangerous game of Himalayan big wall climbing. Audience Award: Dramatic

RACING EXTINCTION / U.S.A. (Director: Louie Psihoyos) — Academy Award-winner Louie Psihoyos (The Cove) assembles a unique team to show the world never-before-seen images that expose issues surrounding endangered species and mass extinction. Whether infiltrating notorious black markets or exploring humans’ effect on the environment, Racing Extinction will change the way you see the world.

(T)ERROR/ U.S.A. (Directors: Lyric R. Cabral, David Felix Sutcliffe) — (T)ERROR is the first film to document on camera a covert counterterrorism sting as it unfolds. Through the perspective of *******, a 63-year-old Black revolutionary turned FBI informant, viewers are given an unprecedented glimpse of the government’s counterterrorism tactics, and the murky justifications behind them. BEST BREAKOUT FILM

WELCOME TO LEITH / U.S.A. (Directors: Michael Beach Nichols, Christopher K. Walker) — A white supremacist attempts to take over a small town in North Dakota.

WESTERN / U.S.A., Mexico (Directors: Bill Ross, Turner Ross) — For generations, all that distinguished Eagle Pass, Texas, from Piedras Negras, Mexico, was the Rio Grande. But when darkness descends upon these harmonious border towns, a cowboy and lawman face a new reality that threatens their way of life. Western portrays timeless American figures in the grip of unforgiving change.

WESTERN / U.S.A., Mexico (Directors: Bill Ross, Turner Ross) — For generations, all that distinguished Eagle Pass, Texas, from Piedras Negras, Mexico, was the Rio Grande. But when darkness descends upon these harmonious border towns, a cowboy and lawman face a new reality that threatens their way of life. Western portrays timeless American figures in the grip of unforgiving change.

THE WOLFPACK / U.S.A. (Director: Crystal Moselle) — Six bright teenage brothers have spent their entire lives locked away from society in a Manhattan housing project. All they know of the outside is gleaned from the movies they watch obsessively (and recreate meticulously). Yet as adolescence looms, they dream of escape, ever more urgently, into the beckoning world. Grand Jury Prize: Documentary

W O R L D C I N E M A D R A M A T I C C O M P E T I T I O N

Twelve films from emerging filmmaking talents around the world offer fresh perspectives and inventive styles.

CLORO (Chlorine) / Italy (Director: Lamberto Sanfelice, Screenwriters: Lamberto Sanfelice, Elisa Amoruso) — Jenny, 17, dreams of becoming a synchronized swimmer. Family events turn her life upside down and she is forced to move to a remote area to look after her ill father and younger brother. It won’t be long before Jenny starts pursuing her dreams again. Cast: Sara Serraiocco, Ivan Franek, Giorgio Colangeli, Anatol Sassi, Piera Degli Esposti, Andrea Vergoni. World Premiere

CHORUS/ Canada (Director and screenwriter: François Delisle) — A separated couple meet again after 10 years when the body of their missing son is found. Amid the guilt of losing a loved one, they hesitantly move toward affirmation of life, acceptance of death, and even the possibility of reconciliation. Cast: Sébastien Ricard, Fanny Mallette, Pierre Curzi, Genevieve Bujold. World Premiere

CHORUS/ Canada (Director and screenwriter: François Delisle) — A separated couple meet again after 10 years when the body of their missing son is found. Amid the guilt of losing a loved one, they hesitantly move toward affirmation of life, acceptance of death, and even the possibility of reconciliation. Cast: Sébastien Ricard, Fanny Mallette, Pierre Curzi, Genevieve Bujold. World Premiere

GLASSLAND/ Ireland (Director and screenwriter: Gerard Barrett) — In a desperate attempt to reunite his broken family, a young taxi driver becomes entangled in the criminal underworld. Cast: Jack Reynor, Toni Collette, Will Poulter, Michael Smiley. International Premiere. World Cinema Special Jury Prize for Acting:Jack Reynor

HOMESICK/ Norway (Director: Anne Sewitsky, Screenwriters: Ragnhild Tronvoll, Anne Sewitsky) — When Charlotte, 27, meets her brother Henrik, 35, for the first time, two people who don’t know what a normal family is begin an encounter without boundaries. How does sibling love manifest itself if you have never experienced it before? Cast: Ine Marie Wilmann, Simon J. Berger, Anneke von der Lippe, Silje Storstein, Oddgeir Thune, Kari Onstad. World Premiere

IVY/ Turkey (Director and screenwriter: Tolga Karaçelik) — Sarmasik is sailing to Egypt when the ship’s owner goes bankrupt. The crew learns there is a lien on the ship, and key crew members must stay on board. Ivy is the story of these six men trapped on the ship for days. Cast: Nadir Sarıbacak, Özgür Emre Yıldırım, Hakan Karsak, Kadir Çermik, Osman Alkaş, Seyithan Özdemiroğlu. World Premiere

IVY/ Turkey (Director and screenwriter: Tolga Karaçelik) — Sarmasik is sailing to Egypt when the ship’s owner goes bankrupt. The crew learns there is a lien on the ship, and key crew members must stay on board. Ivy is the story of these six men trapped on the ship for days. Cast: Nadir Sarıbacak, Özgür Emre Yıldırım, Hakan Karsak, Kadir Çermik, Osman Alkaş, Seyithan Özdemiroğlu. World Premiere

PARTISAN/ Australia (Director: Ariel Kleiman, Screenwriters: Ariel Kleiman, Sarah Cyngler) — Alexander is like any other kid: playful, curious and naive. He is also a trained assassin. Raised in a hidden paradise, Alexander has grown up seeing the world filtered through his father, Gregori. As Alexander begins to think for himself, creeping fears take shape, and Gregori’s idyllic world unravels. Cast: Vincent Cassel, Jeremy Chabriel, Florence Mezzara. World Dramatic Award for Cinematography.

PRINCESS / Israel (Director and screenwriter: Tali Shalom Ezer) — While her mother is away from home, 12-year-old Adar’s role-playing games with her stepfather move into dangerous territory. Seeking an escape, Adar finds Alan, an ethereal boy that accompanies her on a dark journey between reality and fantasy. Cast: Keren Mor, Shira Haas, Ori Pfeffer, Adar Zohar Hanetz. International Premiere

THE SECOND MOTHER / Brazil (Director and screenwriter: Anna Muylaert) — Having left her daughter, Jessica, to be raised by relatives in the north of Brazil, Val works as a loving nanny in São Paulo. When Jessica arrives for a visit 13 years later, she confronts her mother’s slave-like attitude and everyone in the house is affected by her unexpected behavior. Cast: Regina Casé, Michel Joelsas, Camila Márdila, Karine Teles, Lourenço Mutarelli. World Premiere

SLOW WEST / New Zealand (Director and screenwriter: John Maclean) — Set at the end of the nineteenth century, 16-year-old Jay Cavendish journeys across the American frontier in search of the woman he loves. He is joined by Silas, a mysterious traveler, and hotly pursued by an outlaw along the way. Cast: Kodi Smit-McPhee, Michael Fassbender, Ben Mendelsohn, Caren Pistorius, Rory McCann. World Premiere. World Cinema Jury Prize: Dramatic WINNER

SLOW WEST / New Zealand (Director and screenwriter: John Maclean) — Set at the end of the nineteenth century, 16-year-old Jay Cavendish journeys across the American frontier in search of the woman he loves. He is joined by Silas, a mysterious traveler, and hotly pursued by an outlaw along the way. Cast: Kodi Smit-McPhee, Michael Fassbender, Ben Mendelsohn, Caren Pistorius, Rory McCann. World Premiere. World Cinema Jury Prize: Dramatic WINNER

STRANGER LAND / Australia, Ireland (Director: Kim Farrant, Screenwriters: Fiona Seres, Michael Kinirons) — When Catherine and Matthew Parker’s two teenage kids disappear into the remote Australian desert, the couple’s relationship is pushed to the brink as they confront the mystery of their children’s fate. Cast: Nicole Kidman, Joseph Fiennes, Hugo Weaving, Lisa Flanagan, Meyne Wyatt, Maddison Brown. World Premiere

THE SUMMER OF SANGAILE/ Lithuania, France, Holland (Director and screenwriter: Alanté Kavaïté) — Seventeen-year-old Sangaile is fascinated by stunt planes. She meets a girl her age at the summer aeronautical show, nearby her parents’ lakeside villa. Sangaile allows Auste to discover her most intimate secret and in the process finds in her teenage love, the only person that truly encourages her to fly. Cast: Julija Steponaitytė, Aistė Diržiūtė. World Premiere. DAY ONE FILM. World Cinema Directing Award: Dramatic – Alanté Kavaïté

UMRIKA / India (Director and screenwriter: Prashant Nair) — When a young village boy discovers that his brother, long believed to be in America, has actually gone missing, he begins to invent letters on his behalf to save their mother from heartbreak, all the while searching for him. Cast: Suraj Sharma, Tony Revolori, Smita Tambe, Adil Hussain, Rajesh Tailang, Prateik Babbar. World Premiere. World Cinema Audience Award: Dramatic

W O R L D C I N E M A D O C U M E N T A R Y C O M P E T I T I O N

W O R L D C I N E M A D O C U M E N T A R Y C O M P E T I T I O N

Twelve documentaries by some of the most courageous and extraordinary international filmmakers working today.

THE AMINA PROFILE / Canada (Director: Sophie Deraspe) — During the Arab revolution, a love story between two women — a Canadian and a Syrian American — turns into an international sociopolitical thriller spotlighting media excesses and the thin line between truth and falsehood on the Internet. World Premiere

CENSORED VOICES / Israel, Germany (Director: Mor Loushy) — One week after the 1967 Six-Day War, renowned author Amos Oz and editor Avraham Shapira recorded intimate conversations with soldiers returning from the battlefield. The Israeli army censored the recordings, allowing only a fragment of the conversations to be published. Censored Voices reveals these recordings for the first time. World Premiere

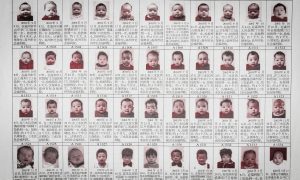

THE CHINESE MAYOR/ China (Director: Hao Zhou) — Mayor Geng Yanbo is determined to transform the coal-mining center of Datong, in China’s Shanxi province, into a tourism haven showcasing clean energy. In order to achieve that, however, he has to relocate 500,000 residences to make way for the restoration of the ancient city. World Premiere

THE CHINESE MAYOR/ China (Director: Hao Zhou) — Mayor Geng Yanbo is determined to transform the coal-mining center of Datong, in China’s Shanxi province, into a tourism haven showcasing clean energy. In order to achieve that, however, he has to relocate 500,000 residences to make way for the restoration of the ancient city. World Premiere

Chuck Norris vs Communism / United Kingdom, Romania, Germany (Director: Ilinca Calugareanu) — In 1980s Romania, thousands of Western films smashed through the Iron Curtain, opening a window to the free world for those who dared to look. A black market VHS racketeer and courageous female translator brought the magic of film to the masses and sowed the seeds of a revolution. World Premiere

DARK HORSE / United Kingdom (Director: Louise Osmond) — Dark Horse is the inspirational true story of a group of friends from a workingman’s club who decide to take on the elite “sport of kings” and breed themselves a racehorse. Showing how animals can unite the community in a common interest and cause, Osmond’s film has been well-received at the festival’s first showings. World Premiere

DARK HORSE / United Kingdom (Director: Louise Osmond) — Dark Horse is the inspirational true story of a group of friends from a workingman’s club who decide to take on the elite “sport of kings” and breed themselves a racehorse. Showing how animals can unite the community in a common interest and cause, Osmond’s film has been well-received at the festival’s first showings. World Premiere

DREAMCATCHER/ United Kingdom (Director: Kim Longinotto) — Dreamcatcher takes us into a hidden world seen through the eyes of one of its survivors, Brenda Myers-Powell. A former teenage prostitute, Brenda defied the odds to become a powerful advocate for change in her community. With warmth and humor, Brenda gives hope to those who have none. World Premiere – World Cinema Directing Award: Documentary – SEE OUR ROTTERDAM REVIEW

HOW TO CHANGE THE WORLD/ United Kingdom, Canada (Director: Jerry Rothwell) — In 1971, a group of friends sails into a nuclear test zone, and their protest captures the world’s imagination. Using rare, archival footage that brings their extraordinary world to life, How to Change the World is the story of the pioneers who founded Greenpeace and defined the modern green movement. World Premiere. DAY ONE FILM

LISTEN TO ME, MARLON / United Kingdom (Director and screenwriter: Stevan Riley, Co-writer: Peter Ettedgui) — With exclusive access to previously unheard audio archives, this is the definitive Marlon Brando cinema documentary. Charting his exceptional career and extraordinary life away from the stage and screen, the film fully explores the complexities of the man by telling the story uniquely in Marlon’s own voice. World Premiere

PERVERT PARK/ Sweden, Denmark (Directors: Frida Barkfors, Lasse Barkfors) — Pervert Park follows the everyday lives of sex offenders in a Florida trailer park as they struggle to reintegrate into society, and try to understand who they are and how to break the cycle of sex crimes being committed. International Premiere

PERVERT PARK/ Sweden, Denmark (Directors: Frida Barkfors, Lasse Barkfors) — Pervert Park follows the everyday lives of sex offenders in a Florida trailer park as they struggle to reintegrate into society, and try to understand who they are and how to break the cycle of sex crimes being committed. International Premiere

THE RUSSIAN WOODPECKER / United Kingdom (Director: Chad Gracia) — A Ukrainian victim of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster discovers a dark secret and must decide whether to risk his life by revealing it, amid growing clouds of revolution and war. World Premiere. World Cinema Jury Prize: Documentary

SEMBENE! / U.S.A., Senegal (Directors: Samba Gadjigo, Jason Silverman) — In 1952, Ousmane Sembene, a Senegalese dockworker and fifth-grade dropout, began dreaming an impossible dream: to become the storyteller for a new Africa. This true story celebrates how the “father of African cinema,” against enormous odds, fought a monumental, 50-year-long battle to give Africans a voice. World Premiere

SEMBENE! / U.S.A., Senegal (Directors: Samba Gadjigo, Jason Silverman) — In 1952, Ousmane Sembene, a Senegalese dockworker and fifth-grade dropout, began dreaming an impossible dream: to become the storyteller for a new Africa. This true story celebrates how the “father of African cinema,” against enormous odds, fought a monumental, 50-year-long battle to give Africans a voice. World Premiere

THE VISIT/ Denmark, Austria, Ireland, Finland, Norway (Director: Michael Madsen) — “This film documents an event that has never taken place…” With unprecedented access to the United Nations’ Office for Outer Space Affairs, leading space scientists and space agencies, The Visit explores humans’ first encounter with alien intelligent life and thereby humanity itself. “Our scenario begins with the arrival. Your arrival.” World Premiere

N E X T

Pure, bold works distinguished by an innovative, forward-thinking approach to storytelling populate this program. Digital technology paired with unfettered creativity promises that the films in this section will shape a “greater” next wave in American cinema. Presented by Adobe.

BOB AND THE TREES/ U.S.A., France (Director: Diego Ongaro, Screenwriters: Diego Ongaro, Courtney Maum, Sasha Statman-Weil) — Bob, a 50-year-old logger in rural Massachusetts with a soft spot for golf and gangsta rap, is struggling to make ends meet in a changed economy. When his beloved cow is wounded and a job goes awry, Bob begins to heed the instincts of his ever-darkening self. Cast: Bob Tarasuk, Matt Gallagher, Polly MacIntyre, Winthrop Barrett, Nathaniel Gregory. World Premiere

CHRISTMAS, AGAIN / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Charles Poekel) — A heartbroken Christmas tree salesman returns to New York, hoping to put the past year behind him. He spends the season living in a trailer and working the night shift, until a mysterious woman and some colorful customers rescue him from self-destruction. Cast: Kentucker Audley, Hannah Gross, Jason Shelton, Oona Roche. North American Premiere

CRONIES/ U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Michael Larnell) — Twenty-two-year-old Louis doesn’t know whether his childhood friendship with Jack will last beyond today. Cast: George Sample III, Zurich Buckner, Brian Kowalski. World Premiere

ENTERTAINMENT / U.S.A. (Director: Rick Alverson, Screenwriters: Rick Alverson, Gregg Turkington, Tim Heidecker) — En route to meeting with his estranged daughter, in an attempt to revive his dwindling career, a broken, aging comedian plays a string of dead-end shows in the Mojave Desert. Cast: Gregg Turkington, John C. Reilly, Tye Sheridan, Michael Cera, Amy Seimetz, Lotte Verbeek. World Premiere

ENTERTAINMENT / U.S.A. (Director: Rick Alverson, Screenwriters: Rick Alverson, Gregg Turkington, Tim Heidecker) — En route to meeting with his estranged daughter, in an attempt to revive his dwindling career, a broken, aging comedian plays a string of dead-end shows in the Mojave Desert. Cast: Gregg Turkington, John C. Reilly, Tye Sheridan, Michael Cera, Amy Seimetz, Lotte Verbeek. World Premiere

H. / U.S.A., Argentina (Directors and screenwriters: Rania Attieh, Daniel Garcia) — Two women, each named Helen, find their lives spinning out of control after a meteor allegedly explodes over their city of Troy, New York. Cast: Robin Bartlett, Rebecca Dayan, Will Janowitz, Julian Gamble, Roger Robinson. World Premiere

JAMES WRIGHT/ U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Josh Mond) — A young New Yorker struggles to take control of his reckless, self-destructive behavior in the face of momentous family challenges. Cast: Chris Abbott, Cynthia Nixon, Scott Mescudi, Makenzie Leigh, David Call. World Premiere. BEST OF NEXT AWARD

NASTY BABY / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Sebastian Silva) — A gay couple try to have a baby with the help of their best friend, Polly. The trio navigates the idea of creating life while confronted by unexpected harassment from a neighborhood man called The Bishop. As their clashes grow increasingly aggressive, odds are someone is getting hurt. Cast: Sebastian Silva, Kristin Wiig, Tunde Adebimpe, Alia Shawkat, Mark Margolis, Reg E. Cathey. World Premiere

THE STRONGEST MAN / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Kenny Riches) — An anxiety-ridden Cuban man who fancies himself the strongest man in the world attempts to recover his most prized possession, a stolen bicycle. On his quest, he finds and loses much more. Cast: Robert Lorie, Paul Chamberlain, Ashly Burch, Patrick Fugit, Lisa Banes. World Premiere

TAKE ME TO THE RIVER / U.S.A. (Director and screenwriter: Matt Sobel) — A naive California teen plans to remain above the fray at his Nebraskan family reunion, but a strange encounter places him at the center of a long-buried family secret. Cast: Logan Miller, Robin Weigert, Josh Hamilton, Richard Schiff, Ursula Parker, Azura Skye. World Premiere

TANGERINE / U.S.A. (Director: Sean Baker, Screenwriters: Sean Baker, Chris Bergoch) — A working girl tears through Tinseltown on Christmas Eve searching for the pimp who broke her heart. Cast: Kitana Kiki Rodriguez, Mya Taylor, Karren Karagulian, Mickey O’Hagan, Alla Tumanyan, James Ransone. World Premiere –

TANGERINE / U.S.A. (Director: Sean Baker, Screenwriters: Sean Baker, Chris Bergoch) — A working girl tears through Tinseltown on Christmas Eve searching for the pimp who broke her heart. Cast: Kitana Kiki Rodriguez, Mya Taylor, Karren Karagulian, Mickey O’Hagan, Alla Tumanyan, James Ransone. World Premiere –

SUNDANCE RUNS FROM 22 JANUARY UNTIL 1 FEBRUARY 2015 IN PARK CITY, UTAH, AMERICA

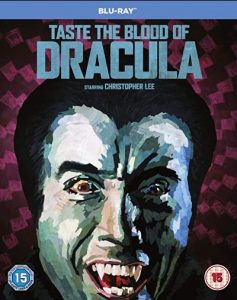

Atmospherically directed by Hungarian Peter Sasdy, and adapted for the screen by Anthony Hinds – stepping in due to budgetary constraints under the pseudonym of John Elder (he told his neighbours he was a hairdresser to avoid publicity throughout his entire career) this outing actually broadens the storyline into a damning social satire of Victorian repression and upper class ennui. The eclectic cast has Christopher Lee, Geoffrey Keen and Gwen Watford and sees three distinguished English gentlemen (Keen, Peter Sallis and John Carson) descend into Satanism, for want of anything better to do, accidentally killIng Dracula‘s sidekick Lord Courtly (Ralph Bates), in the process. As an act of revenge the Count vows they will die at the hands of their own children. But Lee actually bloodies the waters in the second half, swanning in glowering due to his lack of a domineering role in the proceedings.

Atmospherically directed by Hungarian Peter Sasdy, and adapted for the screen by Anthony Hinds – stepping in due to budgetary constraints under the pseudonym of John Elder (he told his neighbours he was a hairdresser to avoid publicity throughout his entire career) this outing actually broadens the storyline into a damning social satire of Victorian repression and upper class ennui. The eclectic cast has Christopher Lee, Geoffrey Keen and Gwen Watford and sees three distinguished English gentlemen (Keen, Peter Sallis and John Carson) descend into Satanism, for want of anything better to do, accidentally killIng Dracula‘s sidekick Lord Courtly (Ralph Bates), in the process. As an act of revenge the Count vows they will die at the hands of their own children. But Lee actually bloodies the waters in the second half, swanning in glowering due to his lack of a domineering role in the proceedings.

A sense of the Gothic also infiltrates No Room at the Inn set in the early months of 1940. We witness atmospheric blitzed streets by the railway bridge next to a rundown house that’s definitely on the wrong side of the tracks: all lorded over by Mrs Agatha Voray (Freda Jackson) doing her damn best not to properly look after three young girl evacuees. The children live in squalor and suffer mental and physical abuse under the care of this coarse woman who invites men (local councillors and shopkeepers) for casual sex and bit of cash to bolster her shopping allowance of ration coupons.

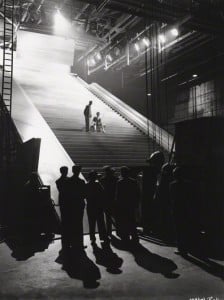

A sense of the Gothic also infiltrates No Room at the Inn set in the early months of 1940. We witness atmospheric blitzed streets by the railway bridge next to a rundown house that’s definitely on the wrong side of the tracks: all lorded over by Mrs Agatha Voray (Freda Jackson) doing her damn best not to properly look after three young girl evacuees. The children live in squalor and suffer mental and physical abuse under the care of this coarse woman who invites men (local councillors and shopkeepers) for casual sex and bit of cash to bolster her shopping allowance of ration coupons. Films don’t always end up the way their makers originally envisaged at their outset, and the maiden production of Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger’s Archers Films would have turned out completely differently had Laurence Olivier been freed from the Fleet Air Arm to make it; since it is now impossible to imagine without third-billed Roger Livesey and his distinctive voice in the title role (in which at the age of 36 he convincingly ages forty years). The makers’ relative inexperience shows in the fact that they ended up with a initial cut over two and a half hours long; but fortunately J.Arthur Rank liked the film so much he let it hit cinemas as it was. Indeed, it was Pressburger’s favourite of the Rank outings, and would go on to influence the work of future filmmakers such as Scorsese in his The Age of Innocence and Tarantino who copied the device of beginning and ending a film be rerunning the same scene from the point of view of different characters.

Films don’t always end up the way their makers originally envisaged at their outset, and the maiden production of Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger’s Archers Films would have turned out completely differently had Laurence Olivier been freed from the Fleet Air Arm to make it; since it is now impossible to imagine without third-billed Roger Livesey and his distinctive voice in the title role (in which at the age of 36 he convincingly ages forty years). The makers’ relative inexperience shows in the fact that they ended up with a initial cut over two and a half hours long; but fortunately J.Arthur Rank liked the film so much he let it hit cinemas as it was. Indeed, it was Pressburger’s favourite of the Rank outings, and would go on to influence the work of future filmmakers such as Scorsese in his The Age of Innocence and Tarantino who copied the device of beginning and ending a film be rerunning the same scene from the point of view of different characters.

L

L

The former artistic director of the Royal Academy Tim Marlow takes us round Lucian Freud’s first and only exhibition at the London gallery (until 26 January 2020). Although Freud is seen as a modern artist his work is very much connected to that ‘old master’, painterly tradition of Titian and Rembrandt: Few modern artists have explored the human body with such intensity, and such determination. Of course, he was a gambler, a playboy and a bon viveur, but few artists spent as much time in their studio as Lucian Freud. The RA’s Andrea Tarsia explains how he pitted his developing style against his personal life, scrutinising himself as much as his subjects. His single-minded passion focused on self-portraiture as much as on those his was painting:. “Everything is a self-portrait”. Often his subjects are not even named: what mattered more to him was the immediacy of the situation, the spontaneity of the gaze. Accompanied by a jazzy score the doc conveys the energy and charisma that seems to spin off each hypnotic portrait, even a small canvas can dominate a room.

The former artistic director of the Royal Academy Tim Marlow takes us round Lucian Freud’s first and only exhibition at the London gallery (until 26 January 2020). Although Freud is seen as a modern artist his work is very much connected to that ‘old master’, painterly tradition of Titian and Rembrandt: Few modern artists have explored the human body with such intensity, and such determination. Of course, he was a gambler, a playboy and a bon viveur, but few artists spent as much time in their studio as Lucian Freud. The RA’s Andrea Tarsia explains how he pitted his developing style against his personal life, scrutinising himself as much as his subjects. His single-minded passion focused on self-portraiture as much as on those his was painting:. “Everything is a self-portrait”. Often his subjects are not even named: what mattered more to him was the immediacy of the situation, the spontaneity of the gaze. Accompanied by a jazzy score the doc conveys the energy and charisma that seems to spin off each hypnotic portrait, even a small canvas can dominate a room. A sensuality entered the artist’s work in the late 1950s and early 1960 where an emphasis on touch starts to appear. This is most noticeable during a trip to Ian Fleming’s Golden Eye when he painted a Flemish style portrait on a small scrap of copper. It sees him putting his finger on his lips and was the start of this sensuous awareness. The 1960s also marked a switch to hog-hair brushes with ‘Man’s Head’ (1963) and the restless associated portraits, smooth backgrounds allowing the face to stand out. Although Freud admired Francis Bacon’s style of working in a gestural way, his own work increasingly gained a more structural, almost architectural element, as he slotted colours together with pasty brushstrokes, trying to make the paint tell the story.

A sensuality entered the artist’s work in the late 1950s and early 1960 where an emphasis on touch starts to appear. This is most noticeable during a trip to Ian Fleming’s Golden Eye when he painted a Flemish style portrait on a small scrap of copper. It sees him putting his finger on his lips and was the start of this sensuous awareness. The 1960s also marked a switch to hog-hair brushes with ‘Man’s Head’ (1963) and the restless associated portraits, smooth backgrounds allowing the face to stand out. Although Freud admired Francis Bacon’s style of working in a gestural way, his own work increasingly gained a more structural, almost architectural element, as he slotted colours together with pasty brushstrokes, trying to make the paint tell the story. Lucian Freud’s large 1993 self-portrait is defiant – he was 71, but still emanated power and excitement; his greatest fear was losing his mind, but he was also concerned about his physical vigour. ‘Benefits Supervisor Sleeping’ (1995) sold in 2008 for 33.6million dollars – the highest price ever paid for a work by a living artist. Freud carried on painting voraciously until his death on 20 July 2011. He was 88. “Being with him was like being plugged into the National Grid for an hour” said one sitter. “Freud was one of the great European painters of the last 500 years. He’s one of those big figures across the centuries, rather than representative of an era or a movement” says Tim Marlow. “Tradition is a big word but Lucian challenged tradition constantly”. Jasper Sharp adds him to a list that goes back to Holbein; Durer; Cranach and Rembrandt. And he goes on: “Freud gives that list a little shuffle, making us look at Rembrandt a bit differently and Holbein a bit differently through his eyes, and through himself”. And that is a remarkable achievement for any artist. MT

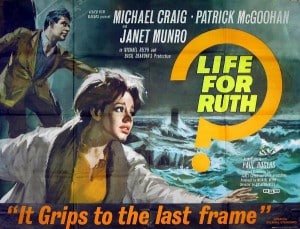

Lucian Freud’s large 1993 self-portrait is defiant – he was 71, but still emanated power and excitement; his greatest fear was losing his mind, but he was also concerned about his physical vigour. ‘Benefits Supervisor Sleeping’ (1995) sold in 2008 for 33.6million dollars – the highest price ever paid for a work by a living artist. Freud carried on painting voraciously until his death on 20 July 2011. He was 88. “Being with him was like being plugged into the National Grid for an hour” said one sitter. “Freud was one of the great European painters of the last 500 years. He’s one of those big figures across the centuries, rather than representative of an era or a movement” says Tim Marlow. “Tradition is a big word but Lucian challenged tradition constantly”. Jasper Sharp adds him to a list that goes back to Holbein; Durer; Cranach and Rembrandt. And he goes on: “Freud gives that list a little shuffle, making us look at Rembrandt a bit differently and Holbein a bit differently through his eyes, and through himself”. And that is a remarkable achievement for any artist. MT Dir: Joseph Losey | 97′ UK Crime drama

Dir: Joseph Losey | 97′ UK Crime drama Dir: John Guillermin | Script: Bryan Forbes | Cast: M E Clifton Jones, John Mills, Maureen Connell, Cecil Parker, Patrick Allen, Leslie Philips, Barbara Hicks, Sidney James, John Le Mesurier, Marius Goring, Michael Hordern | War Drama | UK 101′

Dir: John Guillermin | Script: Bryan Forbes | Cast: M E Clifton Jones, John Mills, Maureen Connell, Cecil Parker, Patrick Allen, Leslie Philips, Barbara Hicks, Sidney James, John Le Mesurier, Marius Goring, Michael Hordern | War Drama | UK 101′

What could be more romantic than a train journey? Even if it feels more like a boys own adventure, as many of these British Transport films do. Escaping into the unknown with a promise of excitement and discovery – or just a trip back in time to revisit childhood holidays in the 1960s and 1970s, where the English landscape stretched far and wide from the window of the pullman out of Waterloo, or even Paddington, and not an anorak in sight!

What could be more romantic than a train journey? Even if it feels more like a boys own adventure, as many of these British Transport films do. Escaping into the unknown with a promise of excitement and discovery – or just a trip back in time to revisit childhood holidays in the 1960s and 1970s, where the English landscape stretched far and wide from the window of the pullman out of Waterloo, or even Paddington, and not an anorak in sight!

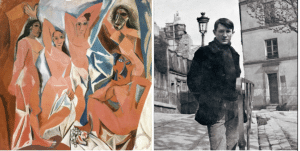

The Young Picasso

The Young Picasso  We spoke to Competition Jury member Lynne Ramsay to talk about her latest project and the film that most impressed her as a child growing up in Glasgow.

We spoke to Competition Jury member Lynne Ramsay to talk about her latest project and the film that most impressed her as a child growing up in Glasgow. Dir: Tony Richardson | Writers: Shelagh Delaney, Tony Richardson | Cast: Rita Tushingham, Murray Melvin, Dora Bryan, John Danquah, Robert Stephens | UK | Drama | 101′

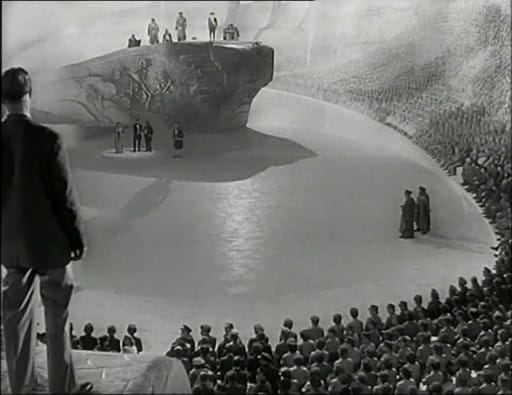

Dir: Tony Richardson | Writers: Shelagh Delaney, Tony Richardson | Cast: Rita Tushingham, Murray Melvin, Dora Bryan, John Danquah, Robert Stephens | UK | Drama | 101′ KHARTOUM is the kind of spectacular, rousing historical adventure that doesn’t get made anymore, certainly not along the same lines as Basil Dearden’s star-studded epic that exposes English colonialism, religious fanaticism, heroism and sacrifice in a magnificent visual masterpiece. Back in the day, it all seemed perfectly harmless to our innocent childhood eyes as we sat round the telly oblivious to the political incorrectness. And that wasn’t the worst thing: it later emerged that over a hundred horses were severely injured or killed immediately during the battle scenes, due to unethical stunt methods of the time.

KHARTOUM is the kind of spectacular, rousing historical adventure that doesn’t get made anymore, certainly not along the same lines as Basil Dearden’s star-studded epic that exposes English colonialism, religious fanaticism, heroism and sacrifice in a magnificent visual masterpiece. Back in the day, it all seemed perfectly harmless to our innocent childhood eyes as we sat round the telly oblivious to the political incorrectness. And that wasn’t the worst thing: it later emerged that over a hundred horses were severely injured or killed immediately during the battle scenes, due to unethical stunt methods of the time. John Schlesinger’s YANKS, a moving and romantic WWII tale of love starring Richard Gere and Vanessa Redgrave is based on Lancashire born Colin Welland’s original story, he also wrote the script.

John Schlesinger’s YANKS, a moving and romantic WWII tale of love starring Richard Gere and Vanessa Redgrave is based on Lancashire born Colin Welland’s original story, he also wrote the script. Dir.: Simon Hunter; Cast: Sheila Hancock, Kevin Guthrie, Amy Mason, Wendy Morgan; UK 2017, 102 min.

Dir.: Simon Hunter; Cast: Sheila Hancock, Kevin Guthrie, Amy Mason, Wendy Morgan; UK 2017, 102 min. Director Margaret Salmon, who made the hyper realist fantasy drama Eglantine (2016) develops her worthwhile and enchanting filmic forays into the natural world that started with P.S. in 2002, and continued with Everything That Rises Must Converge (2010); Enemies of the Rose (2011); Gibraltar (2013); Pyramid (2014) and Bird (2016), amongst other titles. Very much festival fare, but valuable in their thoughtful exploration of the British Isles, and often further afield. MT

Director Margaret Salmon, who made the hyper realist fantasy drama Eglantine (2016) develops her worthwhile and enchanting filmic forays into the natural world that started with P.S. in 2002, and continued with Everything That Rises Must Converge (2010); Enemies of the Rose (2011); Gibraltar (2013); Pyramid (2014) and Bird (2016), amongst other titles. Very much festival fare, but valuable in their thoughtful exploration of the British Isles, and often further afield. MT The lineup for the 2018 BFI London Film Festival has been announced, and the public box office is open. The 12-day festival will show over 225 feature-length films from all over the globe – so here are some of the best we’ve seen from this year’s international festival circuit.

The lineup for the 2018 BFI London Film Festival has been announced, and the public box office is open. The 12-day festival will show over 225 feature-length films from all over the globe – so here are some of the best we’ve seen from this year’s international festival circuit.

WOMAN AT WAR (2018) – SACD Winner, Cannes Film Festival 2018

WOMAN AT WAR (2018) – SACD Winner, Cannes Film Festival 2018 THE FAVOURITE

THE FAVOURITE

DOGMAN Best Actor, Marcello Forte, Cannes 2018 | Palm Dog Winner 2018

DOGMAN Best Actor, Marcello Forte, Cannes 2018 | Palm Dog Winner 2018  MADELINE’S MADELINE

MADELINE’S MADELINE MUSEUM – Best Script Berlinale 2018

MUSEUM – Best Script Berlinale 2018 IN FABRIC

IN FABRIC THE WILD PEAR TREE – Palme d’Or, Cannes 2018

THE WILD PEAR TREE – Palme d’Or, Cannes 2018  THEY’LL LOVE ME WHEN I’M DEAD (2018)

THEY’LL LOVE ME WHEN I’M DEAD (2018) Dir: Billy Wilder | Writers: Billy Wilder, Harry Kurnitz, Lawrence B Marcus | Cast: Marlene Dietrich, Tyrone Power, Charles Laughton, Elsa Lanchester, John Williams, Torin Thatcher, Norma Varden, Una O’Connor | US Crime Drama | 116′

Dir: Billy Wilder | Writers: Billy Wilder, Harry Kurnitz, Lawrence B Marcus | Cast: Marlene Dietrich, Tyrone Power, Charles Laughton, Elsa Lanchester, John Williams, Torin Thatcher, Norma Varden, Una O’Connor | US Crime Drama | 116′ Dir: Lance Comfort | Cast: Simone Simon, Robert Newton, William Hartnell, Margaret Barton | Noir Thriller | UK |

Dir: Lance Comfort | Cast: Simone Simon, Robert Newton, William Hartnell, Margaret Barton | Noir Thriller | UK | The Closing Night will be the UK Premiere of

The Closing Night will be the UK Premiere of  There will be two retrospectives in honour of non-fiction filmmaking: The innovative found footage documentarian Penny Lane and Japanese pioneer of ‘action documentary’, Kazuo Hara. Both filmmakers will be at the festival to present their work.

There will be two retrospectives in honour of non-fiction filmmaking: The innovative found footage documentarian Penny Lane and Japanese pioneer of ‘action documentary’, Kazuo Hara. Both filmmakers will be at the festival to present their work. Open City Documentary Festival is looking forward to hosting a number of exciting festival parties this year including the Opening and Closing Night Receptions at the Regent Street Cinema as well as the Nabihah Iqbal after-party at the ICA, where the DJ, Producer & NTS Radio presenter presents an evening of music inspired by 1972 documentary Winter Soldier, featuring protest songs and music from the anti-war movement from 1950-1975. Other various festival parties will be listed in the festival programme.

Open City Documentary Festival is looking forward to hosting a number of exciting festival parties this year including the Opening and Closing Night Receptions at the Regent Street Cinema as well as the Nabihah Iqbal after-party at the ICA, where the DJ, Producer & NTS Radio presenter presents an evening of music inspired by 1972 documentary Winter Soldier, featuring protest songs and music from the anti-war movement from 1950-1975. Other various festival parties will be listed in the festival programme. THE MICHAEL POWELL AWARD FOR BEST BRITISH FEATURE FILM

THE MICHAEL POWELL AWARD FOR BEST BRITISH FEATURE FILM THE AWARD FOR BEST PERFORMANCE IN A BRITISH FEATURE FILM

THE AWARD FOR BEST PERFORMANCE IN A BRITISH FEATURE FILM THE AWARD FOR BEST INTERNATIONAL FEATURE FILM

THE AWARD FOR BEST INTERNATIONAL FEATURE FILM THE AWARD FOR BEST DOCUMENTARY FEATURE FILM

THE AWARD FOR BEST DOCUMENTARY FEATURE FILM Dir: Paul Van Carter | Doc | UK |

Dir: Paul Van Carter | Doc | UK | Woodfall Film Productions was founded in 1958 by English director Tony Richardson (1928-1991), the American producer Harry Saltzman (later of James Bond fame) and the English author and playwright John Osborne, whose play Look back in Anger was filmed by Richardson in 1959 as the opus number of the company that championed the British New Wave. So it’s only fitting that Richardson should finish the circle in 1984 with Hotel New Hampshire, creating a sub-genre of dram-com, which was later developed by Wes Anderson.

Woodfall Film Productions was founded in 1958 by English director Tony Richardson (1928-1991), the American producer Harry Saltzman (later of James Bond fame) and the English author and playwright John Osborne, whose play Look back in Anger was filmed by Richardson in 1959 as the opus number of the company that championed the British New Wave. So it’s only fitting that Richardson should finish the circle in 1984 with Hotel New Hampshire, creating a sub-genre of dram-com, which was later developed by Wes Anderson. The Entertainer featured Laurence Olivier in the title role, reprising his stage role from the Royal Court, co-written by John Osborne from his own play. There is nothing heroic about Olivier’s Archie Rice: he is a bankrupt womaniser, exploiting his long suffering wife Phoebe (de Banzie) and using Tina Lapford (Field) – who came second in the Miss Britain contest – and her wealthy family to prolong his stage career. Not even the death of his son in the Suez conflict can deter him from his vain pursuit of a long dead career. Using his father – who dies on stage – for his own advantage, Archie sinks deeper and deeper. There is a poignant scene with his film daughter Jean (Plowright), whom he asks: “What would think, if I married a woman your age?” and Jean answers exasperated “Oh. Daddy”. At the end of productions, Olivier would marry Plowright, after his divorce from Vivien Leigh. Shot partly at Margate, this is a bleak portrait of show business, shot in brilliant black and white by the great Oswald Morris (Moby Dick, A Farewell to Arms).

The Entertainer featured Laurence Olivier in the title role, reprising his stage role from the Royal Court, co-written by John Osborne from his own play. There is nothing heroic about Olivier’s Archie Rice: he is a bankrupt womaniser, exploiting his long suffering wife Phoebe (de Banzie) and using Tina Lapford (Field) – who came second in the Miss Britain contest – and her wealthy family to prolong his stage career. Not even the death of his son in the Suez conflict can deter him from his vain pursuit of a long dead career. Using his father – who dies on stage – for his own advantage, Archie sinks deeper and deeper. There is a poignant scene with his film daughter Jean (Plowright), whom he asks: “What would think, if I married a woman your age?” and Jean answers exasperated “Oh. Daddy”. At the end of productions, Olivier would marry Plowright, after his divorce from Vivien Leigh. Shot partly at Margate, this is a bleak portrait of show business, shot in brilliant black and white by the great Oswald Morris (Moby Dick, A Farewell to Arms).  Set in a desolate Manchester, A Taste of Honey would make a star of the lead actor Rita Tushingham. She plays 17-year old school girl Jo, who is totally neglected by her sex-mad mother Helen (Bryan), who only has time for her fiancée Robert (Stephens). Jo gets pregnant by the black sailor Jimmy (Danquah), who soon leaves with his ship. Jo befriends the textile student Geoffrey, a brilliant Murray Melvin, who is not sure about his sexual orientation. He looks lovingly after her, before Helen returns, after having been rejected by Robert. She shucks Geoffrey out, and pretends to look after her daughter and the baby, whilst having one eye on the next, potential suitor. A Taste of Honey is relentlessly gloomy and discouraging. Photographed innovatively

Set in a desolate Manchester, A Taste of Honey would make a star of the lead actor Rita Tushingham. She plays 17-year old school girl Jo, who is totally neglected by her sex-mad mother Helen (Bryan), who only has time for her fiancée Robert (Stephens). Jo gets pregnant by the black sailor Jimmy (Danquah), who soon leaves with his ship. Jo befriends the textile student Geoffrey, a brilliant Murray Melvin, who is not sure about his sexual orientation. He looks lovingly after her, before Helen returns, after having been rejected by Robert. She shucks Geoffrey out, and pretends to look after her daughter and the baby, whilst having one eye on the next, potential suitor. A Taste of Honey is relentlessly gloomy and discouraging. Photographed innovatively Nothing could be more different than Richardson’s next project, the historical romp Tom Jones, based on the novel by Henry Fielding. Albert Finney is the bumptious titular hero, who is nearly hanged due to the schemes by his adversary Bliflil (the debut for David Warner). With a great love story involving Sophie Western (York) and her father (Griffith), there are some great performances by Edith Evans, Joan Greenwood and Diane Cilento. Like his auteur Richardson, Lassally changes style effortlessly in this colourful wide-screen bonanza. It would garner an Oscar for Richardson, and was a huge success at the box office: the slender budget of £467000 pounds would result in a cool 70 million takings. AS

Nothing could be more different than Richardson’s next project, the historical romp Tom Jones, based on the novel by Henry Fielding. Albert Finney is the bumptious titular hero, who is nearly hanged due to the schemes by his adversary Bliflil (the debut for David Warner). With a great love story involving Sophie Western (York) and her father (Griffith), there are some great performances by Edith Evans, Joan Greenwood and Diane Cilento. Like his auteur Richardson, Lassally changes style effortlessly in this colourful wide-screen bonanza. It would garner an Oscar for Richardson, and was a huge success at the box office: the slender budget of £467000 pounds would result in a cool 70 million takings. AS An Evening With Beverly Luff Linn (Director: Jim Hosking,

An Evening With Beverly Luff Linn (Director: Jim Hosking, Eighth Grade (Director/Screenwriter: Bo Burnham) – Thirteen-year-old Kayla endures the tidal wave of contemporary suburban adolescence as she makes her way through the last week of middle school — the end of her thus far disastrous eighth grade year — before she begins high school.

Eighth Grade (Director/Screenwriter: Bo Burnham) – Thirteen-year-old Kayla endures the tidal wave of contemporary suburban adolescence as she makes her way through the last week of middle school — the end of her thus far disastrous eighth grade year — before she begins high school. Generation Wealth (Director: Lauren Greenfield) – Lauren Greenfield’s postcard from the edge of the American Empire captures a portrait of a materialistic, image-obsessed culture. Simultaneously personal journey and historical essay, the film bears witness to the global boom–bust economy, the corrupted American Dream and the human costs of late stage capitalism, narcissism and greed.

Generation Wealth (Director: Lauren Greenfield) – Lauren Greenfield’s postcard from the edge of the American Empire captures a portrait of a materialistic, image-obsessed culture. Simultaneously personal journey and historical essay, the film bears witness to the global boom–bust economy, the corrupted American Dream and the human costs of late stage capitalism, narcissism and greed. Half the Picture (Director: Amy Adrion) – At a pivotal moment for gender equality in Hollywood, successful women directors tell the stories of their art, lives and careers. Having endured a long history of systemic discrimination, women filmmakers may be getting the first glimpse of a future that values their voices equally.

Half the Picture (Director: Amy Adrion) – At a pivotal moment for gender equality in Hollywood, successful women directors tell the stories of their art, lives and careers. Having endured a long history of systemic discrimination, women filmmakers may be getting the first glimpse of a future that values their voices equally. Hereditary (Director/Screenwriter: Ari Aster) – After their reclusive grandmother passes away, the Graham family tries to escape the dark fate they’ve inherited.

Hereditary (Director/Screenwriter: Ari Aster) – After their reclusive grandmother passes away, the Graham family tries to escape the dark fate they’ve inherited. Leave No Trace (Director: Debra Granik, Screenwriters: Debra Granik, Anne Rosellini) – A father and daughter live a perfect but mysterious existence in Forest Park, a beautiful nature reserve near Portland, Oregon, rarely making contact with the world. A small mistake tips them off to authorities sending them on an increasingly erratic journey in search of a place to call their own.

Leave No Trace (Director: Debra Granik, Screenwriters: Debra Granik, Anne Rosellini) – A father and daughter live a perfect but mysterious existence in Forest Park, a beautiful nature reserve near Portland, Oregon, rarely making contact with the world. A small mistake tips them off to authorities sending them on an increasingly erratic journey in search of a place to call their own. The Miseducation of Cameron Post (Director: Desiree Akhavan, Screenwriters: Desiree Akhavan, Cecilia Frugiuele) –1993: after being caught having sex with the prom queen, a girl is forced into a gay conversion therapy center. Based on Emily Danforth’s acclaimed and controversial coming-of-age novel.

The Miseducation of Cameron Post (Director: Desiree Akhavan, Screenwriters: Desiree Akhavan, Cecilia Frugiuele) –1993: after being caught having sex with the prom queen, a girl is forced into a gay conversion therapy center. Based on Emily Danforth’s acclaimed and controversial coming-of-age novel. Never Goin’ Back (Director/Screenwriter: Augustine Frizzell) –Jessie and Angela, high school dropout BFFs, are taking a week off to chill at the beach. Too bad their house got robbed, rent’s due, they’re about to get fired and they’re broke. Now they’ve gotta avoid eviction, stay out of jail and get to the beach, no matter what!!!

Never Goin’ Back (Director/Screenwriter: Augustine Frizzell) –Jessie and Angela, high school dropout BFFs, are taking a week off to chill at the beach. Too bad their house got robbed, rent’s due, they’re about to get fired and they’re broke. Now they’ve gotta avoid eviction, stay out of jail and get to the beach, no matter what!!! Skate Kitchen (Director: Crystal Moselle, Screenwriters: Crystal Moselle, Ashlihan Unaldi) – Camille’s life as a lonely suburban teenager changes dramatically when she befriends a group of girl skateboarders. As she journeys deeper into this raw New York City subculture, she begins to understand the true meaning of friendship as well as her inner self.

Skate Kitchen (Director: Crystal Moselle, Screenwriters: Crystal Moselle, Ashlihan Unaldi) – Camille’s life as a lonely suburban teenager changes dramatically when she befriends a group of girl skateboarders. As she journeys deeper into this raw New York City subculture, she begins to understand the true meaning of friendship as well as her inner self. The Tale (Director/Screenwriter: Jennifer Fox) – An investigation into one woman’s memory as she’s forced to re-examine her first sexual relationship and the stories we tell ourselves in order to survive; based on the filmmaker’s own story.

The Tale (Director/Screenwriter: Jennifer Fox) – An investigation into one woman’s memory as she’s forced to re-examine her first sexual relationship and the stories we tell ourselves in order to survive; based on the filmmaker’s own story. Yardie (Director: Idris Elba, Screenwriters: Brock Norman Brock, Martin Stellman) – Jamaica, 1973. When a young boy witnesses his brother’s assassination, a powerful Don gives him a home. Ten years later he is sent on a mission to London. He reunites with his girlfriend and their daughter, but then the past catches up with them. Based on Victor Headley’s novel.

Yardie (Director: Idris Elba, Screenwriters: Brock Norman Brock, Martin Stellman) – Jamaica, 1973. When a young boy witnesses his brother’s assassination, a powerful Don gives him a home. Ten years later he is sent on a mission to London. He reunites with his girlfriend and their daughter, but then the past catches up with them. Based on Victor Headley’s novel. The Crowhurst story has spawned various theatrical and literary adaptations, and even a chamber opera: The Strange Last Voyage of Donald Crowhurst. Eric Colvin plays him in Simon Rumley’s upcoming low budget indie thriller Crowhurst which purportedly features the actual vessel that set sail in the endeavour.

The Crowhurst story has spawned various theatrical and literary adaptations, and even a chamber opera: The Strange Last Voyage of Donald Crowhurst. Eric Colvin plays him in Simon Rumley’s upcoming low budget indie thriller Crowhurst which purportedly features the actual vessel that set sail in the endeavour. Firth is brilliantly cast as Crowhurst – blending just the right amount of pathos and self-belief in his portrait of an unsatisfactory businessman of a rather nervous disposition who can’t take pressure and lacks personal conviction (possibly due to his mother dressing him as a much wanted girl until the age of 17). His marriage is clearly happy and Rachel Weisz plays his wife as a typically supportive English rose, stalwart in her affections and a brilliant mum but rather passive and naive in a commercial sense, as most women were in the those days.

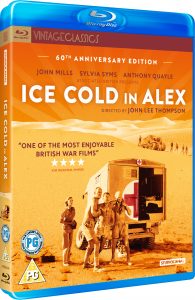

Firth is brilliantly cast as Crowhurst – blending just the right amount of pathos and self-belief in his portrait of an unsatisfactory businessman of a rather nervous disposition who can’t take pressure and lacks personal conviction (possibly due to his mother dressing him as a much wanted girl until the age of 17). His marriage is clearly happy and Rachel Weisz plays his wife as a typically supportive English rose, stalwart in her affections and a brilliant mum but rather passive and naive in a commercial sense, as most women were in the those days. Dir: J Lee Thompson | Cast: John Mills, Sylvia Syms, Anthony Quayle | UK | 122’

Dir: J Lee Thompson | Cast: John Mills, Sylvia Syms, Anthony Quayle | UK | 122’

The 22nd edition of the London Human Rights Watch Film Festival opens in time for

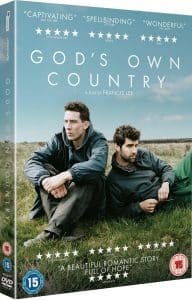

The 22nd edition of the London Human Rights Watch Film Festival opens in time for  Dir.: Francis Lee; Cast: Josh O’Connor, Alec Secareanu, Gemma Jones, Ian Hart; UK 2017, 104 min.

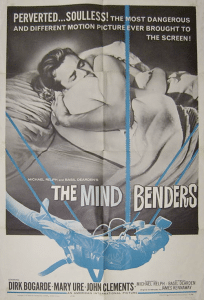

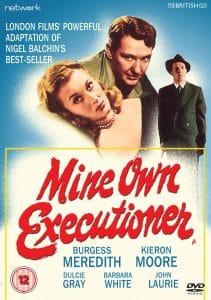

Dir.: Francis Lee; Cast: Josh O’Connor, Alec Secareanu, Gemma Jones, Ian Hart; UK 2017, 104 min. Dir: Anthony Kimmins | Writer: Nigel Balchin | Psychological Drama | UK | Burgess Meredith, Barbara White, Kieron Moore, Dulcie Gray

Dir: Anthony Kimmins | Writer: Nigel Balchin | Psychological Drama | UK | Burgess Meredith, Barbara White, Kieron Moore, Dulcie Gray Hollywood may still be struggling with female representation as 2018 gets underway, but Europe has seen tremendous successes in the world of indie film where talented women of all ages are winning accolades in every sphere of the film industry, bringing their unique vision and intuition to a party that has continued to rock throughout the past year. Admittedly, there have been some really fabulous female roles recently – probably more so than for male actors. But on the other side of the camera, women have also created some thumping dramas; robust documentaries and bracingly refreshing genre outings: Lucrecia Martel’s mesmerising Argentinian historical fantasy ZAMA (LFF/left) and Julia Ducournau’s Belgo-French horror drama RAW (below/right) have been amongst the most outstanding features in recent memory. All these films provide great insight into the challenges women continue to face, both personally and in society as a whole, and do so without resorting to worthiness or sentimentality. So as we go forward into another year, here’s a flavour of what’s been happening in 2017.

Hollywood may still be struggling with female representation as 2018 gets underway, but Europe has seen tremendous successes in the world of indie film where talented women of all ages are winning accolades in every sphere of the film industry, bringing their unique vision and intuition to a party that has continued to rock throughout the past year. Admittedly, there have been some really fabulous female roles recently – probably more so than for male actors. But on the other side of the camera, women have also created some thumping dramas; robust documentaries and bracingly refreshing genre outings: Lucrecia Martel’s mesmerising Argentinian historical fantasy ZAMA (LFF/left) and Julia Ducournau’s Belgo-French horror drama RAW (below/right) have been amongst the most outstanding features in recent memory. All these films provide great insight into the challenges women continue to face, both personally and in society as a whole, and do so without resorting to worthiness or sentimentality. So as we go forward into another year, here’s a flavour of what’s been happening in 2017. It all started at SUNDANCE in January where documentarian Pascale Lamche’s engrossing film about Winnie Mandela, WINNIE, won Best World Doc and Maggie Betts was awarded a directing prize for her debut feature NOVITIATE, about a nun struggling to take and keep her vows in 1960s Rome. Eliza Hitman also bagged the coveted directing award for her gay-themed indie drama BEACH RATS, that looks at addiction from a young boy’s perspective.

It all started at SUNDANCE in January where documentarian Pascale Lamche’s engrossing film about Winnie Mandela, WINNIE, won Best World Doc and Maggie Betts was awarded a directing prize for her debut feature NOVITIATE, about a nun struggling to take and keep her vows in 1960s Rome. Eliza Hitman also bagged the coveted directing award for her gay-themed indie drama BEACH RATS, that looks at addiction from a young boy’s perspective. Meanwhile, back in Europe, BERLIN‘s Golden Bear went to Hungarian filmmaker Ildiko Enyedi (right) for her thoughtful and inventive exploration of adult loneliness and alienation BODY AND SOUL. Agnieska Holland won a Silver Bear for her green eco feature SPOOR, and Catalan newcomer Carla Simón went home with a prize for her feature debut SUMMER 1993 tackling the more surprising aspects of life for an orphaned child who goes to live with her cousins. CANNES 2017, the festival’s 70th celebration, also proved to be another strong year for female talent. Claire Simon’s first comedy – looking at love in later life – LET THE SUNSHINE IN was well-received and provided a playful role for Juliette Binoche, which she performed with gusto. Agnès Varda’s entertaining travel piece FACES PLACES took us all round France and finally showed Jean-Luc Godard’s true colours, winning awards at TIFF and Cannes. Newcomers were awarded in the shape of Léa Mysius whose AVA won the SACD prize for its tender exploration of oncoming blindness, and Léonor Séraille whose touching drama about the after-effects of romantic abandonment MONTPARNASSE RENDEZVOUS won the Caméra D’Or.

Meanwhile, back in Europe, BERLIN‘s Golden Bear went to Hungarian filmmaker Ildiko Enyedi (right) for her thoughtful and inventive exploration of adult loneliness and alienation BODY AND SOUL. Agnieska Holland won a Silver Bear for her green eco feature SPOOR, and Catalan newcomer Carla Simón went home with a prize for her feature debut SUMMER 1993 tackling the more surprising aspects of life for an orphaned child who goes to live with her cousins. CANNES 2017, the festival’s 70th celebration, also proved to be another strong year for female talent. Claire Simon’s first comedy – looking at love in later life – LET THE SUNSHINE IN was well-received and provided a playful role for Juliette Binoche, which she performed with gusto. Agnès Varda’s entertaining travel piece FACES PLACES took us all round France and finally showed Jean-Luc Godard’s true colours, winning awards at TIFF and Cannes. Newcomers were awarded in the shape of Léa Mysius whose AVA won the SACD prize for its tender exploration of oncoming blindness, and Léonor Séraille whose touching drama about the after-effects of romantic abandonment MONTPARNASSE RENDEZVOUS won the Caméra D’Or. The Doyenne of French contemporary cinema Isabelle Huppert won Best Actress in LOCARNO 2017 for her performance as a woman who morphs from a meek soul to a force to be reckoned with when she is struck by lightening, in Serge Bozon’s dark comedy MADAME HYDE. Huppert has been winning accolades since the 1970s but she still has to challenge Hollywood’s Ann Doran (1911-2000) on film credits (374) – but there is plenty of time!). Meanwhile, Nastassja Kinski was awarded a Lifetime Achievement Honour for her extensive and eclectic contribution to World cinema (Paris,Texas, Inland Empire, Cat People and Tess to name a few).

The Doyenne of French contemporary cinema Isabelle Huppert won Best Actress in LOCARNO 2017 for her performance as a woman who morphs from a meek soul to a force to be reckoned with when she is struck by lightening, in Serge Bozon’s dark comedy MADAME HYDE. Huppert has been winning accolades since the 1970s but she still has to challenge Hollywood’s Ann Doran (1911-2000) on film credits (374) – but there is plenty of time!). Meanwhile, Nastassja Kinski was awarded a Lifetime Achievement Honour for her extensive and eclectic contribution to World cinema (Paris,Texas, Inland Empire, Cat People and Tess to name a few). With a Jury headed by Annette Bening, VENICE again showed women in a strong light. Away from the Hollywood-fraught main competition, this year’s Orizzonti Award was awarded to Susanna Nicchiarelli’s NICO, 1988, a stunning biopic of the final years of the renowned model and musician Christa Pfaffen, played by a feisty Trine Dyrholm. And Sara Forestier’s Venice Days winning debut M showed how a stuttering girl and her illiterate boyfriend help each other overcome adversity. Charlotte Rampling won the prize for Best Actress for her portrait of strength in the face of her husbands’ imprisonment in Andrea Pallaoro’s HANNAH.