The first wave of titles have been announced for the first edition of the Chinese Cinema Season. spooling out over the next three months and kicking off on 12 February (Chinese New Year) all over Europe.

The longterm festival will showcase UK Chinese language premieres and highlight overlooked gems and classics to cinema-lovers in the UK and Ireland. New films will be added to the party, along with the usual Q&As and panel discussions with industry professionals, filmmakers and actors, and academics.

Over 50 films will be on offer over the course of the season all available on VOD, along with themed mini retrospectives. Along with Coronavirus this is ‘a love letter’ from China.

Popular films such as festival favourite Youth are available along with a Shanghai Animation strand featuring 10 films from 1950s to the present day. Studio Ghibli is possibly more widely known for Anime titles, but Ghibli’s Hayao Miyaki visited the Shanghai studio back in 1984 setting up his own studio a year later. Features include the delightful Lotus Lantern (1999) a UK premiere.

Documentary wise there will be a chance to see DOUBLE HAPPINESS (2018), A YANGTZE LANDSCAPE (2017) and DAUGHTER OF SHANGHAI (2019).

Double Happiness Limited

Taiwanese director Shen spent seven years detailing eight couples’ lives from falling in love, getting married and having children, getting them to ask each other questions that they would not touch on in their daily lives, and leading the audience to reflect on their own definition of marriage and happiness.

A Yangtze Landscape

Setting off from the Yangtze’s marine port, passing Shanghai, Nanjing, Wuhan, the huge Three Gorges Dam, and Chongqing, all the way to the Yangtze River’s source in Qinghai/Tibet over thousands of kilometres, this unique work of sound and vision utilizes the “Yangtze”, in the director’s words, as a metaphor of the current chaos in China.

Bazzar Jumpers

Three Uyghur friends in love with parkour fight prejudice and family opposition to train for China’s most popular and dangerous parkour event in Beijing.

Daughter of Shanghai

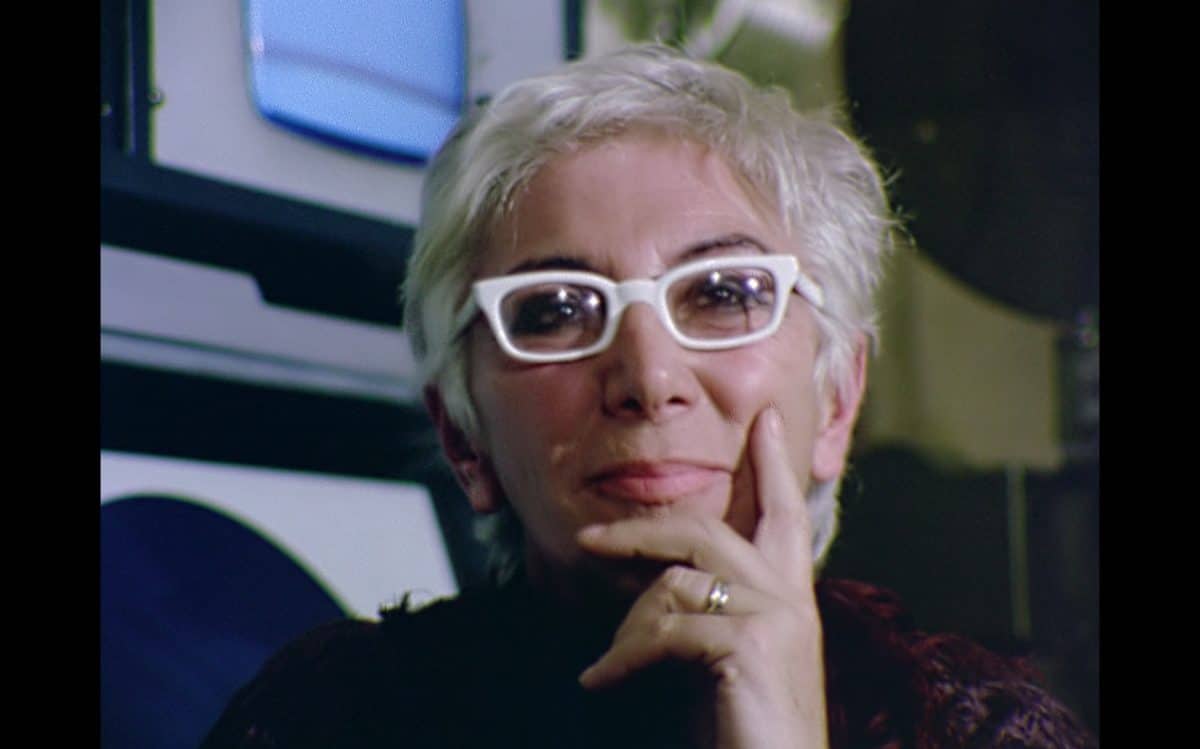

A waltz through the life of Chinese English actress Tsai Chin: the daughter of the Peking Opera master Zhou Xinfang, the first Chinese student at RADA, and the first Chinese Bond Girl. The director Michelle Chen is confirmed to do a Q&A with other contributors TBC to celebrate the premiere of this film.

.

FIRST FILM SPOTLIGHT

12 February to 12 May

This section introduces contemporary Chinese directors and their striking debuts. Three films will be shown in the opening month: A First Farewell (2018) by Lina Wang, The Crossing (2018) by Bai Xue, and The Silent Holy Stone (2006) by Pema Tseden. Encompassing Mandarin, Cantonese (The Crossing), Tibetan (The Silent Holy Stone ) and Uyghur (A First Farewell )dialects and cultures, these films reflect how diverse life can be in the different regions of China.

A First Farewell * UK PREMIERE *

Isa Yassan, a young Muslim boy in Xinjiang Province, balances caring for his ailing mother, schoolwork, and farm duties, soon experiences “the first farewell” in his life – as his father decides to send his mother to a nursing home and they leave the village. Lina Wang, from Xinjiang, wrote and directed this film, which won the Crystal Bear and Special Prize of the Generation Kplus International Jury at Berlin International Film Festival, as well as several other awards at Tokyo, Shanghai and Hong Kong film festivals

The Crossing (above)

Sixteen-year-old Peipei crosses the border between mainland China and Hong Kong every day, customs officials waving her through with just a glimpse of her high school uniform and innocent face. She joins a gang to earn quick money by smuggling iPhones across the border, but soon finds herself in way over her head. The debut from BAFTA Leading Light writer-director Bai Xue, was nominated for Best First Feature Award and Crystal Bear at Berlin International Festival, won the NETPAC Award at Toronto International Film Festival, and best first film awards at Pingyao, Hong Kong, and Dublin Film Festivals.

The Silent Holy Stone

A young Tibetan monk returns home for the New Year and discovers a television which he intends to bring to the monastery and show to his master. Tibetan director Pema Tsedan’s debut, immediately preceding his recent feature Balloon (2019), shows how the director established his personal style from the very beginning.

DOMESTIC HITS

12 February to 12 May

In recent years, the world has witnessed the rise of the Chinese mega-blockbuster and the seemingly unstoppable rise of the film industry in China. this section features commercial films that triumphed at the domestic box-office with relatively high production value. For the opening month the following are showing: Sheep Without a Shepherd (2019), Youth (2017), and The Captain (2019).

Sheep Without a Shepherd

Lee (Xiao Yang) and his wife Jade (Tan Zhuo) run a small

video business in Thailand. They have two lovely daughters and live a happy life. However, when his eldest daughter kills a schoolmate in self-defence during a sexual assault, Lee has to bury the body and cover the truth, to protect his daughter and families, Lawan (an impeccably steely Joan Chen, The Last Emperor, Lust, Caution) is the feared head of the regional police, and she is dying to find her missing son. The contest between Lee and Lawan is beginning. The battle of wills between Lee and Lawan begins. The film’s box office reached more than 1.2 billion RMB in China ($185m), even as the start of the pandemic cut short the film’s release. The film is based on the 2015 Indian box office hit, Drishyam.

Youth

Directed by China’s most famous commercial director Feng Xiaogang, Youth takes a look at the lives of the members of a Military Cultural Troupe back in the 1970s Cultural Revolution, exploring their friendship, love, dreams, and devotion to their beloved collective and career. The storyline, to a large extent comprised of the director’s personal memories and nostalgia, also resonates with a generation in China who sacrificed their youth to the country and the ideology.

The Captain

One of so-called “main melody” films, stemming from a true story, The Captain demonstrates a breath-taking moment: a commercial pilot and his crew try to save passengers and land their plane safely while the plane shatters at 30,000 feet in the air. Its box office reached more than 2 billion RMB in China (over $300m).

Upcoming Sections

Lou Ye Mini Retrospective

As one of the “Sixth Generation” directors, Lou Ye has been regarded as a “true artist”, an “authentic filmmaker” and a “constant fighter” of censorship. Despite the controversies, he achieved great success both in China and worldwide. He was nominated and won numerous awards owing to his unique editing style and camera movement, as well as his sharp observations and narratives about marginalised people and typical, but often undocumented, social phenomena in China. In this section, we will premiere Lou Ye’s penultimate film, Shadow Play, which took two years of editing to get the greenlight from authorities.

The platform is powered by Shift 72 (Cannes Marché du Film, SXSW, Macao IFFAM, Tallinn Black Nights) and tickets can be purchased here

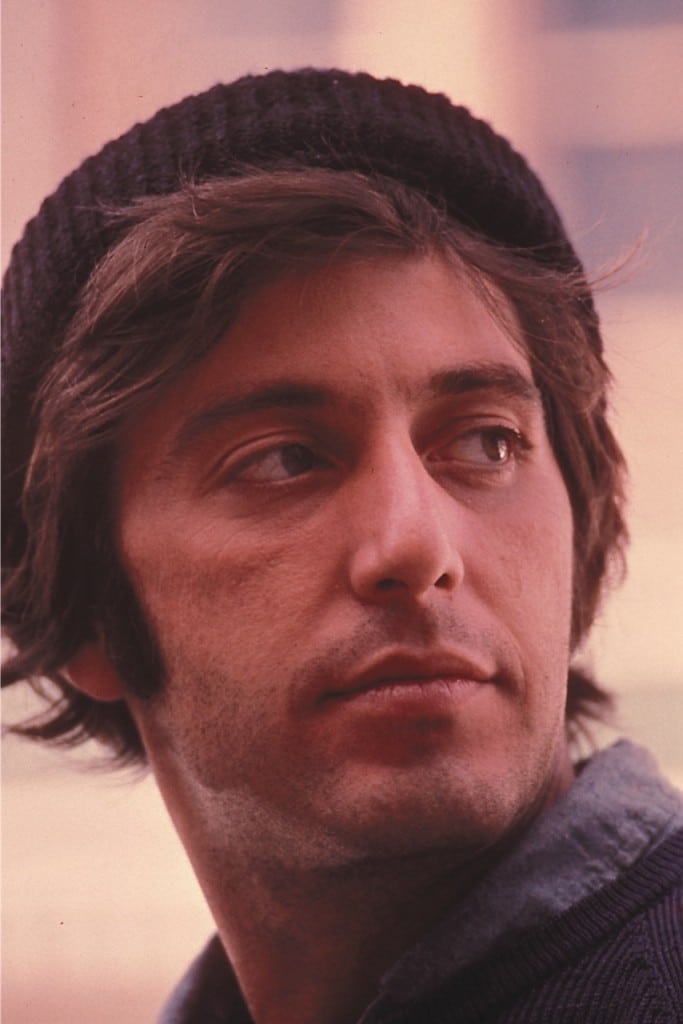

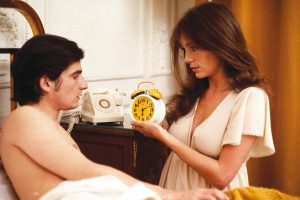

In 1966 Léaud would star in Godard’s Masculin, feminin: 15 Faits Précis, winning a Silver Bear for Best Actor at the Berlinale for his role as Paul, who is in a ménage-a-quatre with three women in a contemporary Paris. Loosely based on Maupassant’s short stories, this feature was the beginning of the break Godard would make with narrative cinema. Also called The Children of Marx and Coca Cola (an inter-title of the feature), sex and politics are at the core. Léaud is fragile, and the lighting shows him as beautiful and vulnerable as the three women, Madeleine (Chantal Goya), Catherine (Isabelle Duport) and Elisabeth (Marlene Jobert). All four main protagonists have very different plans for the future, when their agendas collide. There is immense elegance and beauty here (DoP Willy Kurant), and Godard treats his actors (perhaps for the last time) with more care than in the verbal politics of later films. Pauline Kael called it “that rare achievement: a work of grace in a contemporary setting” and for Andrew Sarris it was “the film of the season”.

In 1966 Léaud would star in Godard’s Masculin, feminin: 15 Faits Précis, winning a Silver Bear for Best Actor at the Berlinale for his role as Paul, who is in a ménage-a-quatre with three women in a contemporary Paris. Loosely based on Maupassant’s short stories, this feature was the beginning of the break Godard would make with narrative cinema. Also called The Children of Marx and Coca Cola (an inter-title of the feature), sex and politics are at the core. Léaud is fragile, and the lighting shows him as beautiful and vulnerable as the three women, Madeleine (Chantal Goya), Catherine (Isabelle Duport) and Elisabeth (Marlene Jobert). All four main protagonists have very different plans for the future, when their agendas collide. There is immense elegance and beauty here (DoP Willy Kurant), and Godard treats his actors (perhaps for the last time) with more care than in the verbal politics of later films. Pauline Kael called it “that rare achievement: a work of grace in a contemporary setting” and for Andrew Sarris it was “the film of the season”. A year later Godard would cast Léaud as part of a group in La Chinoise (1967), this time surrounded by two women and two men, but with a very much harsher political focus. Based on Dostoyevsky’s The Possessed, this was Godard’s first adventure into Maoism. Léaud is Guillaume, in love with Veronique (Anne Wiazemsky), who has a much stronger personality than him, and will finally leave him. Kirilov (Lex de Bruijin), is the weakest of the trio and he will kill himself, as in the novel. Léaud’s Guillaume is in love with Veronique, but he is very much a man of clever words, but little action. Veronique on the other hand, is much braver, and decides in the end to assassinate the Russian Cultural minister on a visit to Paris. But he mixes up the numbers of his hotel room, and kills the wrong man. Wiazemsky, the grand daughter of novelist Andrew Malraux, then the Gaullist minister for Culture, fell in love with Godard, and the couple married after the shooting. As an in-joke, Godard casts Francis Jeanson in the film (Wiazemsky’s philosophy lecturer at the Paris 10 (Nanterre) University) having a debate with Veronique while on her way to assassinate the minister.

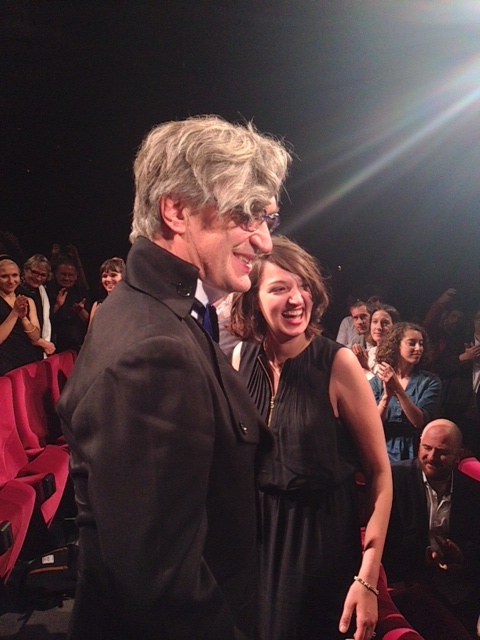

A year later Godard would cast Léaud as part of a group in La Chinoise (1967), this time surrounded by two women and two men, but with a very much harsher political focus. Based on Dostoyevsky’s The Possessed, this was Godard’s first adventure into Maoism. Léaud is Guillaume, in love with Veronique (Anne Wiazemsky), who has a much stronger personality than him, and will finally leave him. Kirilov (Lex de Bruijin), is the weakest of the trio and he will kill himself, as in the novel. Léaud’s Guillaume is in love with Veronique, but he is very much a man of clever words, but little action. Veronique on the other hand, is much braver, and decides in the end to assassinate the Russian Cultural minister on a visit to Paris. But he mixes up the numbers of his hotel room, and kills the wrong man. Wiazemsky, the grand daughter of novelist Andrew Malraux, then the Gaullist minister for Culture, fell in love with Godard, and the couple married after the shooting. As an in-joke, Godard casts Francis Jeanson in the film (Wiazemsky’s philosophy lecturer at the Paris 10 (Nanterre) University) having a debate with Veronique while on her way to assassinate the minister. Truffaut’s 1973 outing La Nuit Americaine (Day for Night), is essentially about filmmaking, showing Léaud as the weak and self-obsessed actor Alphonse. During the filming of Je vous présente Pamela , a conventional weepie, he fancies leading lady Julie Baker (Jacqueline Bisset), who has recently had a breakdown. Out of pity she sleeps with him but Alphonse then ‘phones her analyst, Dr Nelson (David Markham), who has left his own family to live with her, and spills the beans on their fling. Léaud plays the histrionic weakling with great skill. And Truffaut, playing himself as the director, assumes the role of his protector – much as in real life. Godard, who by now had broken with his ex-friend Truffaut, called Day for Night “a big lie” – later the two founding fathers of the Nouvelle Vague fought over Léaud who somehow survived the acrimony and went on to work with another enfant terrible, Finnish director Aki Kaurismaki.

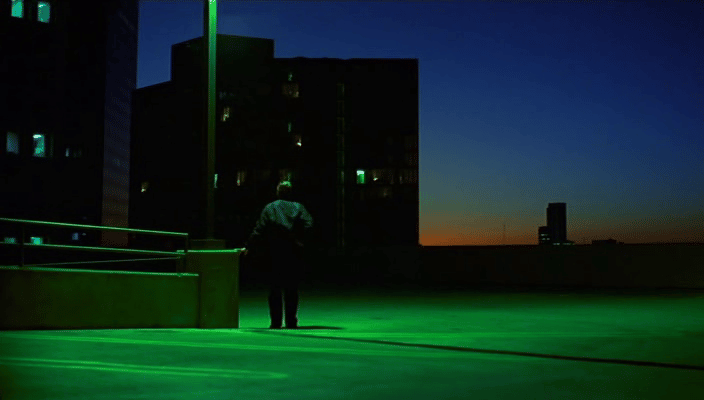

Truffaut’s 1973 outing La Nuit Americaine (Day for Night), is essentially about filmmaking, showing Léaud as the weak and self-obsessed actor Alphonse. During the filming of Je vous présente Pamela , a conventional weepie, he fancies leading lady Julie Baker (Jacqueline Bisset), who has recently had a breakdown. Out of pity she sleeps with him but Alphonse then ‘phones her analyst, Dr Nelson (David Markham), who has left his own family to live with her, and spills the beans on their fling. Léaud plays the histrionic weakling with great skill. And Truffaut, playing himself as the director, assumes the role of his protector – much as in real life. Godard, who by now had broken with his ex-friend Truffaut, called Day for Night “a big lie” – later the two founding fathers of the Nouvelle Vague fought over Léaud who somehow survived the acrimony and went on to work with another enfant terrible, Finnish director Aki Kaurismaki. I hired a Contract Killer (1990) was one of Kaurismaki’s first English language films and he made a beeline for Léaud in the lead role. The gamine actor of Day for Night had since changed dramatically. His slight, almost feminine appearance was gone, and he’d put on a substantial amount of weight – his acting too was from another dimension. He plays Henri Boulanger, an English Civil Servant, who is sacked after fifteen years of service due to privatisation. With no life outside his work, he tries – in vain – to commit suicide. Then asks a contract killer (Kenneth Colley) to step in. But Margaret (Margi Clarke) gives his life a new meaning. With time running out, Henri tries to contact the killer, to reverse the order. Léaud is totally morbid and emotionally reduced, the environment is straight out of the 1950s, the colours pale, bleached out by wear and tear. Léaud’s agile friskiness has been replaced by gentle placidness, making him look much older than forty-six. But his acting had matured too, and he slips easily into character roles nobody would have expected from him in his New Wave days. AS

I hired a Contract Killer (1990) was one of Kaurismaki’s first English language films and he made a beeline for Léaud in the lead role. The gamine actor of Day for Night had since changed dramatically. His slight, almost feminine appearance was gone, and he’d put on a substantial amount of weight – his acting too was from another dimension. He plays Henri Boulanger, an English Civil Servant, who is sacked after fifteen years of service due to privatisation. With no life outside his work, he tries – in vain – to commit suicide. Then asks a contract killer (Kenneth Colley) to step in. But Margaret (Margi Clarke) gives his life a new meaning. With time running out, Henri tries to contact the killer, to reverse the order. Léaud is totally morbid and emotionally reduced, the environment is straight out of the 1950s, the colours pale, bleached out by wear and tear. Léaud’s agile friskiness has been replaced by gentle placidness, making him look much older than forty-six. But his acting had matured too, and he slips easily into character roles nobody would have expected from him in his New Wave days. AS