The Berlin Film Festival – Competition line-up complete

Directors including Benoit Jacquot, Gus Van Sant, Alexey German Jr, Małgorzata Szumowska, Thomas Stuber and Laura Bispuri will compete in this year’s Competition while Isabel Coixet and Lars Kraume feature in the Berlinale Special strand.

Berlinale will open for the first time with an animation feature, Isle of Dogs, by Wes Anderson, in a dazzling line-up of World premieres starring the likes of Joaquin Phoenix, Jonah Hill, Rooney Mara and Jack Black. For Alexei German Jr, this is his second Berlin’s competition title since Under Electric Clouds in 2015. He returns with a feature that follows several days in the life of Russian writer Sergei Dovlatov.

Jacquot’s thriller Eva, played by Isabelle Huppert, a playwright encounters a mysterious woman when he takes shelter in a chalet during a violent snowstorm. The feature is based on James Hadley Chase’s novel Eve is the sixth time the French director Jacquot and Huppert have worked together. Jeanne Moreau originally played her part in a 1962 adaptation directed by Joseph Losey. This latest version World premieres at Sundance in January. Stuber’s drama In The Aisles stars Toni Erdmann actress Sandra Hüller, while Bispuri’s drama Daughter Of Mine, explores a young girl’s relationship with both her biological and adoptive mothers. This is the second time Alexei German Jr’s work plays in competition since his 2015 feature Under Electric Clouds.

Meanwhile, Coixet’s drama The Bookshop sees British Actress Emily Mortimer playing a woman who decides, against polite but ruthless local opposition, to open a bookshop, a decision which becomes a political minefield.

Competition Line-up

U – 22 July (Norway)

Dir: Erik Poppe (The King’s Choice)

Cast: Brede Fristad, Ada Eide, Andrea Berntzen, Ingeborg Enes

World Premiere

7 Days in Entebbe | USA/UK |

7 Days in Entebbe | USA/UK |

Dir: José Padilha (The Elite Squad, Garapa) |

Cast: Rosamund Pike, Daniel Brühl, Eddie Marsan, Lior Ashkenazi, Denis Menochet, Ben Schnetzer

World premiere – Out of competition

Ága | Bulgaria/Ger/France

Ága | Bulgaria/Ger/France

Dir: Milko Lazarov (Otchuzhdenie) | Cast:Mikhail Aprosimov, Feodosia Ivanova, Galina Tikhonova, Sergey Egorov, Afanasiy Kylaev | World premiere – Out of competition

Ang panahon ng halimaw (Season of the Devil) | Philippines

Dir: Lav Diaz (A Lullaby to the Sorrowful Mystery, The Woman Who Left)

Cast: Piolo Pascual, Shaina Magdayao, Pinky Amador, Bituin Escalante, Hazel Orencio, Joel Saracho, Bart Guingona, Angel Aquino, | World premiere

Museo (Museum) | Mex | Dir Alonso Ruizpalacios (Güeros)

Museo (Museum) | Mex | Dir Alonso Ruizpalacios (Güeros)

Cast: Gael García Bernal, Leonardo Ortizgris, Alfredo Castro, Simon Russell Beale, Bernardo Velasco, Leticia Brédice, Ilse Salas, Lisa Owen

World premiere

Unsane | USA

Unsane | USA

By Steven Soderbergh (Traffic, The Good German)

Dir: Claire Foy, Joshua Leonard, Jay Pharoah, Juno Temple, Aimee Mullins, Amy Irving

World premiere – Out of competition

3 Tage in Quiberon 3 DAYS IN QUIBERON

3 Tage in Quiberon 3 DAYS IN QUIBERON

Germany / Austria / France

Dir: Emily Atef (Molly’s Way, The Stranger In Me)

With Marie Bäumer, Birgit Minichmayr, Charly Hübner, Robert Gwisdek, Denis Lavant

World premiere

Black 47

Black 47

Ireland / Luxembourg

By Lance Daly (Kisses, The Good Doctor)

With Hugo Weaving, James Frecheville, Stephen Rea, Freddie Fox, Barry Keoghan, Moe Dunford, Sarah Greene, Jim Broadbent

World premiere – Out of competition

Damsel

Damsel

USA

By David Zellner, Nathan Zellner (Kid-Thing, Kumiko, The Treasure Hunter)

With Robert Pattinson, Mia Wasikowska, David Zellner, Nathan Zellner, Robert Forster, Joe Billingiere | International premiere

Eldorado – Documentary

Eldorado – Documentary

Switzerland / Germany

By Markus Imhoof (The Boat Is Full, More Than Honey)

World premiere – Out of competition

Las herederas (The Heiresses)

Las herederas (The Heiresses)

Paraguay / Germany / Uruguay / Norway / Brazil / France

By Marcelo Martinessi

With Ana Brun, Margarita Irún, Ana Ivanova

World premiere – First Feature

Khook (Pig)

Khook (Pig)

Iran

By Mani Haghighi (Modest Reception, A Dragon Arrives!)

With Hasan Majuni, Leila Hatami, Leili Rashidi, Parinaz Izadyar, Ali Bagheri

World premiere

La prière (The Prayer)

La prière (The Prayer)

France

By Cédric Kahn (Red Lights, Wild Life)

With Anthony Bajon, Damien Chapelle, Alex Brendemühl, Louise Grinberg, Hanna Schygulla

World premiere

Toppen av ingenting (The Real Estate)

Sweden / United Kingdom

By Måns Månsson (The Yard, Mr Governor), Axel Petersén (Avalon)

With Léonore Ekstrand, Christer Levin, Christian Saldert, Olof Rhodin, Carl Johan Merner, Don Bennechi

World premiere

Touch Me Not

Touch Me Not

Romania / Germany / Czech Republic / Bulgaria / France

By Adina Pintilie (Don’t Get Me Wrong)

With Laura Benson, Tómas Lemarquis, Christian Bayerlein, Grit Uhlemann, Hanna Hofmann, Seani Love, Irmena Chichikova

World premiere – First Feature

Transit

Transit

Germany / France

By Christian Petzold (Yella, Barbara, Phoenix)

With Franz Rogowski, Paula Beer, Godehard Giese, Lilien Batman, Maryam Zaree, Barbara Auer, Matthias Brandt, Sebastian Hülk, Emilie de Preissac, Antoine Oppenheim

World premiere

Don’t Worry, He Won’t Get Far on Foot USA

Don’t Worry, He Won’t Get Far on Foot USA

By Gus Van Sant (Milk, Promised Land) | With Joaquin Phoenix, Jonah Hill, Rooney Mara, Jack Black, Udo Kier

World premieres at Sundance.

Dovlatov | Russian Federation / Poland / Serbia | World Premiere | Director: Alexey German Jr. (Paper Soldier, Under Electric Clouds | With Milan Maric, Danila Kozlovsky, Helena Sujecka, Artur Beschastny, Elena Lyadova

Dovlatov | Russian Federation / Poland / Serbia | World Premiere | Director: Alexey German Jr. (Paper Soldier, Under Electric Clouds | With Milan Maric, Danila Kozlovsky, Helena Sujecka, Artur Beschastny, Elena Lyadova

World premiere

Eva | France | World Premiere | Director: Benoit Jacquot (Three Hearts, Diary of a Chambermaid) | With Isabelle Huppert, Gaspard Ulliel, Julia Roy, Richard Berry

Eva | France | World Premiere | Director: Benoit Jacquot (Three Hearts, Diary of a Chambermaid) | With Isabelle Huppert, Gaspard Ulliel, Julia Roy, Richard Berry

World premiere

Figlia mia (Daughter of Mine) | Italy / Germany / Switzerland | Director: Laura Bispuri (Sworn Virgin) With Valeria Golino, Alba Rohrwacher, Sara Casu, Udo Kier | World premiere

Figlia mia (Daughter of Mine) | Italy / Germany / Switzerland | Director: Laura Bispuri (Sworn Virgin) With Valeria Golino, Alba Rohrwacher, Sara Casu, Udo Kier | World premiere

In den Gängen (In the Aisles) | Germany | World Premiere | Director: Thomas Stuber (Teenage Angst, A Heavy Heart) | With Franz Rogowski, Sandra Hüller, Peter Kurth

In den Gängen (In the Aisles) | Germany | World Premiere | Director: Thomas Stuber (Teenage Angst, A Heavy Heart) | With Franz Rogowski, Sandra Hüller, Peter Kurth

Mein Bruder heißt Robert und ist ein Idiot | Germany | World Premi| Direction: Philip Gröning (Into Great Silence, The Police Officer’s Wife | With Josef Mattes, Julia Zange, Urs Jucker, Stefan Konarske, Zita Aretz, Karolina Porcari, Vitus Zeplichal

Twarz (Mug) | Poland | Director: Małgorzata Szumowska (In the Name of, Body) | World Premiere | With Mateusz Kościukiewicz, Agnieszka Podsiadlik, Małgorzata Gorol, Roman Gancarczyk, Dariusz Chojnacki, Robert Talarczyk, Anna Tomaszewska, Martyna Krzysztofik

Twarz (Mug) | Poland | Director: Małgorzata Szumowska (In the Name of, Body) | World Premiere | With Mateusz Kościukiewicz, Agnieszka Podsiadlik, Małgorzata Gorol, Roman Gancarczyk, Dariusz Chojnacki, Robert Talarczyk, Anna Tomaszewska, Martyna Krzysztofik

World Premiere

Berlinale Special Gala

The Bookshop | Spain / United Kingdom / Germany Premiere | Director: Isabel Coixet (Things I Never Told You, My Life Without Me, The Secret Life of Words | With Emily Mortimer, Bill Nighy, Patricia Clarkson

The Bookshop | Spain / United Kingdom / Germany Premiere | Director: Isabel Coixet (Things I Never Told You, My Life Without Me, The Secret Life of Words | With Emily Mortimer, Bill Nighy, Patricia Clarkson

Das schweigende Klassenzimmer (The Silent Revolution) | Germany | Word Premiere | Director: Lars Kraume (The People vs. Fritz Bauer) | With Leonard Scheicher, Tom Gramenz, Lena Klenke, Jonas Dassler, Florian Lukas, Jördis Triebel, Michael Gwisdek, Ronald Zehrfeld, Burghart Klaußner

Das schweigende Klassenzimmer (The Silent Revolution) | Germany | Word Premiere | Director: Lars Kraume (The People vs. Fritz Bauer) | With Leonard Scheicher, Tom Gramenz, Lena Klenke, Jonas Dassler, Florian Lukas, Jördis Triebel, Michael Gwisdek, Ronald Zehrfeld, Burghart Klaußner

Special at the Haus der Berliner Festspiele

Gurrumul – Documentary

Gurrumul – Documentary

Australia

By Paul Williams

International premiere – Debut film

In Cooperation with NATIVe

Viaje a los Pueblos Fumigados – Documentary

Argentina

By Fernando Solanas (The Hour Of The Furnaces, Tangos, The Exile Of Gardel, Memoria del saqueo – A Social Genocide)

World premiere

BERLINALE FILM FESTIVAL 2018 | 15 -25 FEBRUARY 2018 | COMPETITION TITLES

This year’s Berlin International Film Festival is awarding the American actor Willem Defoe with an Honorary Golden Bear in recognition of his career featuring over 100 performances and spanning nearly 40 years since his 1981 debut in Kathryn Bigelow’s debut drama The Loveless. His enormous technical range as an actor extends all the way from the personification of the unfathomably evil to the portrayal of Jesus of Nazareth. In addition to his celebrated cinematic appearances, Dafoe has also pursued a parallel career in theatre, his other passion.

This year’s Berlin International Film Festival is awarding the American actor Willem Defoe with an Honorary Golden Bear in recognition of his career featuring over 100 performances and spanning nearly 40 years since his 1981 debut in Kathryn Bigelow’s debut drama The Loveless. His enormous technical range as an actor extends all the way from the personification of the unfathomably evil to the portrayal of Jesus of Nazareth. In addition to his celebrated cinematic appearances, Dafoe has also pursued a parallel career in theatre, his other passion. Born in Wisconsin in 1955, Willem Dafoe began studying theatre formally at the age of 17. In 1977, he was one of the founding members of the renowned New York theatre ensemble “The Wooster Group”, where he remained a member for several decades. In addition to his activities on stage, Dafoe increasingly began to turn his attention to film work starting in the early 1980s. Walter’s Hill’s Streets of Fire (1984) was soon followed by William Friedkin’s police thriller To Live and Die in L.A. (1985) where he played ruthless counterfeiter Eric “Ric” Masters, a villain who will stop at nothing to rival his adversaries.

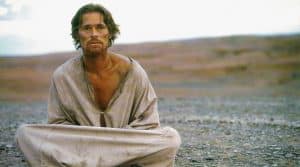

Born in Wisconsin in 1955, Willem Dafoe began studying theatre formally at the age of 17. In 1977, he was one of the founding members of the renowned New York theatre ensemble “The Wooster Group”, where he remained a member for several decades. In addition to his activities on stage, Dafoe increasingly began to turn his attention to film work starting in the early 1980s. Walter’s Hill’s Streets of Fire (1984) was soon followed by William Friedkin’s police thriller To Live and Die in L.A. (1985) where he played ruthless counterfeiter Eric “Ric” Masters, a villain who will stop at nothing to rival his adversaries. In 1986, Dafoe’s portrayal of Sergeant Elias Grodin in Oliver Stone’s anti-war drama Platoon would expose him to a wider audience. He received his first Academy Award nomination for his performance in the break-through film. Two years later, Martin Scorsese successfully recruited him to fill the leading role as Jesus Christ in his hotly debated literary adaptation The Last Temptation of Christ (1988). Still in the same year, Dafoe co-starred alongside Gene Hackman in director Alan Parker’s civil-rights-era drama Mississippi Burning (1988) (right). In the film, Dafoe plays a young FBI agent fighting against racism and the Ku Klux Klan.

In 1986, Dafoe’s portrayal of Sergeant Elias Grodin in Oliver Stone’s anti-war drama Platoon would expose him to a wider audience. He received his first Academy Award nomination for his performance in the break-through film. Two years later, Martin Scorsese successfully recruited him to fill the leading role as Jesus Christ in his hotly debated literary adaptation The Last Temptation of Christ (1988). Still in the same year, Dafoe co-starred alongside Gene Hackman in director Alan Parker’s civil-rights-era drama Mississippi Burning (1988) (right). In the film, Dafoe plays a young FBI agent fighting against racism and the Ku Klux Klan. Many multifaceted roles would follow, in films such as Born on the Fourth of July (1989), Wim Wenders’ In weiter Ferne, so nah! (Faraway, So Close! 1993) and The English Patient (1996). In the year 2000, Dafoe shined as Max Schreck in the horror film Shadow of the Vampire by director E. Elias Merhige. His brilliant turn as a member of the undead earned him his second Academy Award nomination.

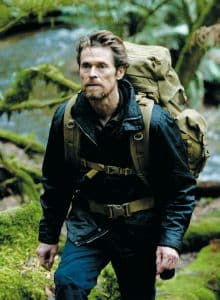

Many multifaceted roles would follow, in films such as Born on the Fourth of July (1989), Wim Wenders’ In weiter Ferne, so nah! (Faraway, So Close! 1993) and The English Patient (1996). In the year 2000, Dafoe shined as Max Schreck in the horror film Shadow of the Vampire by director E. Elias Merhige. His brilliant turn as a member of the undead earned him his second Academy Award nomination. In 2009 Danish director Lars von Trier cast him as the male lead alongside Charlotte Gainsbourg in his psycho-thriller Antichrist – the film became the subject of controversy due to scenes featuring graphic sex and violence. In 2011 Dafoe put on an extraordinary acting performance once again as a lonely hunter in Daniel Nettheim’s thriller The Hunter. Three years later, in Abel Ferrara’s biopic (right) Pasolini Dafoe portrayed the Italian filmmaker in the final period of his life, shortly before his murder.

In 2009 Danish director Lars von Trier cast him as the male lead alongside Charlotte Gainsbourg in his psycho-thriller Antichrist – the film became the subject of controversy due to scenes featuring graphic sex and violence. In 2011 Dafoe put on an extraordinary acting performance once again as a lonely hunter in Daniel Nettheim’s thriller The Hunter. Three years later, in Abel Ferrara’s biopic (right) Pasolini Dafoe portrayed the Italian filmmaker in the final period of his life, shortly before his murder. Last year Dafoe has appeared in Kenneth Branagh’s feature Murder on the Orient Express (2017). The German-American joint effort The Sleeping Shepherd (directed by Frank Hudec) is currently in pre-production. He has also finished filming under the direction of Julian Schnabel for At Eternity’s Gate, in which he plays Vincent van Gogh. Dafoe’s role in The Florida Project earned him both a nomination for the British BAFTA Awards and recently his third nomination for an Academy Award, in the category of Best Supporting Actor.

Last year Dafoe has appeared in Kenneth Branagh’s feature Murder on the Orient Express (2017). The German-American joint effort The Sleeping Shepherd (directed by Frank Hudec) is currently in pre-production. He has also finished filming under the direction of Julian Schnabel for At Eternity’s Gate, in which he plays Vincent van Gogh. Dafoe’s role in The Florida Project earned him both a nomination for the British BAFTA Awards and recently his third nomination for an Academy Award, in the category of Best Supporting Actor. 7 Days in Entebbe | USA/UK |

7 Days in Entebbe | USA/UK | Ága | Bulgaria/Ger/France

Ága | Bulgaria/Ger/France

Museo (Museum) | Mex | Dir Alonso Ruizpalacios (Güeros)

Museo (Museum) | Mex | Dir Alonso Ruizpalacios (Güeros) Unsane | USA

Unsane | USA 3 Tage in Quiberon 3 DAYS IN QUIBERON

3 Tage in Quiberon 3 DAYS IN QUIBERON  Black 47

Black 47  Damsel

Damsel  Eldorado – Documentary

Eldorado – Documentary Las herederas (The Heiresses)

Las herederas (The Heiresses) Khook (Pig)

Khook (Pig) La prière (The Prayer)

La prière (The Prayer) Touch Me Not

Touch Me Not Transit

Transit Don’t Worry, He Won’t Get Far on Foot USA

Don’t Worry, He Won’t Get Far on Foot USA Dovlatov | Russian Federation / Poland / Serbia | World Premiere | Director: Alexey German Jr. (Paper Soldier, Under Electric Clouds | With Milan Maric, Danila Kozlovsky, Helena Sujecka, Artur Beschastny, Elena Lyadova

Dovlatov | Russian Federation / Poland / Serbia | World Premiere | Director: Alexey German Jr. (Paper Soldier, Under Electric Clouds | With Milan Maric, Danila Kozlovsky, Helena Sujecka, Artur Beschastny, Elena Lyadova Eva | France | World Premiere | Director: Benoit Jacquot (Three Hearts, Diary of a Chambermaid) | With Isabelle Huppert, Gaspard Ulliel, Julia Roy, Richard Berry

Eva | France | World Premiere | Director: Benoit Jacquot (Three Hearts, Diary of a Chambermaid) | With Isabelle Huppert, Gaspard Ulliel, Julia Roy, Richard Berry Figlia mia (Daughter of Mine) | Italy / Germany / Switzerland | Director: Laura Bispuri (Sworn Virgin) With Valeria Golino, Alba Rohrwacher, Sara Casu, Udo Kier | World premiere

Figlia mia (Daughter of Mine) | Italy / Germany / Switzerland | Director: Laura Bispuri (Sworn Virgin) With Valeria Golino, Alba Rohrwacher, Sara Casu, Udo Kier | World premiere In den Gängen (In the Aisles) | Germany | World Premiere | Director: Thomas Stuber (Teenage Angst, A Heavy Heart) | With Franz Rogowski, Sandra Hüller, Peter Kurth

In den Gängen (In the Aisles) | Germany | World Premiere | Director: Thomas Stuber (Teenage Angst, A Heavy Heart) | With Franz Rogowski, Sandra Hüller, Peter Kurth Twarz (Mug) | Poland | Director: Małgorzata Szumowska (In the Name of, Body) | World Premiere | With Mateusz Kościukiewicz, Agnieszka Podsiadlik, Małgorzata Gorol, Roman Gancarczyk, Dariusz Chojnacki, Robert Talarczyk, Anna Tomaszewska, Martyna Krzysztofik

Twarz (Mug) | Poland | Director: Małgorzata Szumowska (In the Name of, Body) | World Premiere | With Mateusz Kościukiewicz, Agnieszka Podsiadlik, Małgorzata Gorol, Roman Gancarczyk, Dariusz Chojnacki, Robert Talarczyk, Anna Tomaszewska, Martyna Krzysztofik The Bookshop | Spain / United Kingdom / Germany Premiere | Director: Isabel Coixet (Things I Never Told You, My Life Without Me, The Secret Life of Words | With Emily Mortimer, Bill Nighy, Patricia Clarkson

The Bookshop | Spain / United Kingdom / Germany Premiere | Director: Isabel Coixet (Things I Never Told You, My Life Without Me, The Secret Life of Words | With Emily Mortimer, Bill Nighy, Patricia Clarkson Das schweigende Klassenzimmer (The Silent Revolution) | Germany | Word Premiere | Director: Lars Kraume (The People vs. Fritz Bauer) | With Leonard Scheicher, Tom Gramenz, Lena Klenke, Jonas Dassler, Florian Lukas, Jördis Triebel, Michael Gwisdek, Ronald Zehrfeld, Burghart Klaußner

Das schweigende Klassenzimmer (The Silent Revolution) | Germany | Word Premiere | Director: Lars Kraume (The People vs. Fritz Bauer) | With Leonard Scheicher, Tom Gramenz, Lena Klenke, Jonas Dassler, Florian Lukas, Jördis Triebel, Michael Gwisdek, Ronald Zehrfeld, Burghart Klaußner Gurrumul – Documentary

Gurrumul – Documentary Wim Wenders’ prize-winning classic Der Himmel über Berlin (Wings of Desire, Federal Republic of Germany / France 1987) returns to the screen in a new, digitally restored 4K DCP version. Two guardian angels keep watch over Berlin, until one of them falls in love with a mortal woman. He chooses to become human, giving up his immortality, and an entirely new world is revealed to him. The film was shot on both black-and-white and colour stock. At the time, that required several additional steps in the lab in order to produce a final colour negative, which was several generations removed from the camera negatives. This version, restored by the Wim Wenders Foundation, is based on the original negatives;

Wim Wenders’ prize-winning classic Der Himmel über Berlin (Wings of Desire, Federal Republic of Germany / France 1987) returns to the screen in a new, digitally restored 4K DCP version. Two guardian angels keep watch over Berlin, until one of them falls in love with a mortal woman. He chooses to become human, giving up his immortality, and an entirely new world is revealed to him. The film was shot on both black-and-white and colour stock. At the time, that required several additional steps in the lab in order to produce a final colour negative, which was several generations removed from the camera negatives. This version, restored by the Wim Wenders Foundation, is based on the original negatives; Az én XX. századom (My 20th Century, Hungary / Federal Republic of Germany 1989), the feature debut of the winner of the 2017 Golden Bear, Ildikó Enyedi, is a complex, poetic fairy tale, and an homage to silent movies. Shot in black-and-white, the film follows the very different live of identical twins in Old Europe at the dawn of the 20th century. Using the original camera negative and the magnetic sound track, the film was digitally restored in 4K by the Hungarian National Film Fund – Hungarian National Film Archive, working with Hungarian Filmlab. Cinematographer Tibor Máthé (HSC – Hungarian Society of Cinematographers) supervised the digital grading.

Az én XX. századom (My 20th Century, Hungary / Federal Republic of Germany 1989), the feature debut of the winner of the 2017 Golden Bear, Ildikó Enyedi, is a complex, poetic fairy tale, and an homage to silent movies. Shot in black-and-white, the film follows the very different live of identical twins in Old Europe at the dawn of the 20th century. Using the original camera negative and the magnetic sound track, the film was digitally restored in 4K by the Hungarian National Film Fund – Hungarian National Film Archive, working with Hungarian Filmlab. Cinematographer Tibor Máthé (HSC – Hungarian Society of Cinematographers) supervised the digital grading. Source: Sony Pictures Entertainment, © Columbia Pictures Corporation Inc.

Source: Sony Pictures Entertainment, © Columbia Pictures Corporation Inc. Letyat Zhuravli (The Cranes Are Flying, USSR 1957) by Mikhail Kalatozov was Soviet cinema’s first international hit after World War II. Made during the period of liberalisation that followed Joseph Stalin’s death, this unusual black-and-white film’s expressionist images tell the tragic story of two lovers after Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union. The film brought international fame to Mikhail Kalatozov and his lead actress, Tatiana Samoilova. Letyat Zhuravli was restored by Mosfilm under the leadership of general director Karen Shakhnazarov. The ditigal 2K restoration, on the basis of the original negative, was supervised by the head of restoration Igor Bogdasarov.

Letyat Zhuravli (The Cranes Are Flying, USSR 1957) by Mikhail Kalatozov was Soviet cinema’s first international hit after World War II. Made during the period of liberalisation that followed Joseph Stalin’s death, this unusual black-and-white film’s expressionist images tell the tragic story of two lovers after Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union. The film brought international fame to Mikhail Kalatozov and his lead actress, Tatiana Samoilova. Letyat Zhuravli was restored by Mosfilm under the leadership of general director Karen Shakhnazarov. The ditigal 2K restoration, on the basis of the original negative, was supervised by the head of restoration Igor Bogdasarov. With Tokyo Boshoku (Tokyo Twilight, Japan 1957), Berlinale Classics will provide a rare opportunity to see a largely unknown and seldom shown work by Yasujiro Ozu. The theme of the end of a family living together is one that Japanese directing maestro Yasujiro Ozu often reworks, and here he has given it a dramatic twist. In wintery Tokyo, a family’s silence leads to its breakdown. Tokyo Boshoku, considered Ozu’s most sombre post-war film, was digitally restored in 4K on the basis of the 35mm duplicate negative provided by the Japanese production company Shochiku, managed by Shochiku MediaWorX Inc. Colour correction was led by Ozu’s former assistant cameraman Takashi Kawamata and cinematographer Masashi Chikamori.

With Tokyo Boshoku (Tokyo Twilight, Japan 1957), Berlinale Classics will provide a rare opportunity to see a largely unknown and seldom shown work by Yasujiro Ozu. The theme of the end of a family living together is one that Japanese directing maestro Yasujiro Ozu often reworks, and here he has given it a dramatic twist. In wintery Tokyo, a family’s silence leads to its breakdown. Tokyo Boshoku, considered Ozu’s most sombre post-war film, was digitally restored in 4K on the basis of the 35mm duplicate negative provided by the Japanese production company Shochiku, managed by Shochiku MediaWorX Inc. Colour correction was led by Ozu’s former assistant cameraman Takashi Kawamata and cinematographer Masashi Chikamori. The Berlinale Classics section will open on February 16, 2018, at 5 pm in the Friedrichstadt-Palast with the premiere of the Deutsche Kinemathek’s digital restoration of the 1923 silent film classic Das alte Gesetz (The Ancient Law) directed by E.A. Dupont. ZDF/ARTE commissioned French composer Philippe Schoeller to create new music for this version, which will be presented by the Orchester Jakobsplatz München with Daniel Grossmann at the podium.

The Berlinale Classics section will open on February 16, 2018, at 5 pm in the Friedrichstadt-Palast with the premiere of the Deutsche Kinemathek’s digital restoration of the 1923 silent film classic Das alte Gesetz (The Ancient Law) directed by E.A. Dupont. ZDF/ARTE commissioned French composer Philippe Schoeller to create new music for this version, which will be presented by the Orchester Jakobsplatz München with Daniel Grossmann at the podium. Last year’s Generation strand featured some really hot titles, proving that youth cinema is capable of surprising and entertaining the older generation – not just its key audience. In its 41st edition, Generation reinforces its reputation for presenting ambitious new discoveries in the international contemporary film scene to young people told at eye level.

Last year’s Generation strand featured some really hot titles, proving that youth cinema is capable of surprising and entertaining the older generation – not just its key audience. In its 41st edition, Generation reinforces its reputation for presenting ambitious new discoveries in the international contemporary film scene to young people told at eye level.