Humans are intruders in the film world of Michelangelo Antonioni: they destroy the harmony of nature and society. Only in a few cases, when they act in solidarity with others, do they have a chance to become part of something whole.

Antonioni grew up in Ferrara in the Po Valley not far from the setting of his documentary short GENTE DEL PO (1943-47). Visconti was in the throws of filming Ossessione nearby. Despite its neo-realistic moorings, this is a personal statement: an effort to interpret the world via the moving image, rather than the other way round. Antonioni’s realism is not to show anything natural, humane or dramatic, and particularly not anything like an idea, a thesis. Memory alone forms the model for his art. Memory in the form of images: photos, paintings, writing – they form the basis of his later work – an adventure, where the audience peels off the many layers, like off an onion: a painting, more than once painted over.

Antonioni was already 38 when he made his drama debut with Cronaca Du Un Amore (1950) Superficially a film noir, in the mood of Visconti’s first opus Ossessione, this expressed the overriding existential angst, loneliness and alienation that would permeate his work. Paola and Guido grew up in the same neighbourhood in Ferrara, and want to do away with Paola’s rich husband Enrico Fontana. This is no crime of passion, because Paola and Guido are unable to love, or even imagine a life together – but they both stand to profit from Fontana’s death. And the city of Milan is much more than a background: life here is a reflection of the state of mind of the conspirators: like a drug, the street life full of chaos, the neurotic atmosphere in the cafes. All this is unreal, jungle like: modern urbanity as hell, a central topic of Antonioni’s opus. And he observes his main protagonists often, when they are alone, not only in dramatic scenes. This way, he creates an elliptical structure, with two combustion points: action and echo. As Wenders said: “The strength of the American Cinema is a forward focus, European cinema paints ellipses”.

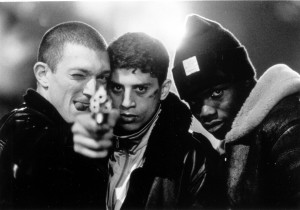

I VINTI (1952) is set in three different countries (Italy, France and the UK), and tells the stories of youthful perpetrators, who commit their crimes not out of material necessity, but just for fun. Even though the crimes are central, Antonioni is not much interested in the structure of the genre. The police work is secondary, as are the criminals themselves: Antonioni is fascinated with the daily life of his protagonists, the crimes are more and more forgotten, the investigations peter out – shades of L’ Avventura and Blow Up.

In LE AMICHE (1955) Antonioni finds the structure for his features, seemingly overpopulated with couples and friends – who are all busy, but play a secondary role to their environment, in this case Turin. Clelia who comes to Turin, to open a designer shop for clothes, falls in with four other young women, all of them much wealthier than she is. Their changing couplings with men end tragically. Set between Clelia’s arrival in Turin and her leaving for Rome, LE AMICHE is a kaleidoscope of human frailty, in which the audience is waiting for something to happen, some sort of story of boy meets girl story, but when something like it really happens, it is so secondary, so much overlaid by all the small details we have learned before, that we are as dislocated as the characters: we flounder because Antonioni does not tell a story with a beginning and an end (however much we pretend), but he tells us, that the world can exist without stories. Because there is so much more to see in the city of Turin, as there will be in Rome: Clelia is only the messenger, send out by Antonioni to be a traveller, not a story teller. In so far, she is his archetypal heroine.

Aldo, the central protagonist in IL GRIDO (1956/7) is the most untypical of all Antonioni heroes: he has been expelled from paradise, after his wife left him. His travels are romantic, because he does not let himself go, but sticks to his environment, travelling with his daughter in the Po delta. Whilst looking back on his village, towered over by the factory chimney, it is his past history, which forces him to leave. He becomes more and more marginalised: an outsider, even when living near the river in a derelict hut, he becomes the victim of the environment, of the background of landscape, seasons and the history of his live, spent all here. El Grido ends tragically, because Aldo (unlike most other Antonioni heroes) insists on keeping to his past: he does not want to cross the bridges, which are metaphorically there to be crossed. And Aldo’s titular outcry becomes a good-bye, even though he is back home. Il Grido is also Antonioni’s return to neo-realism, another contradiction, because he never really was part of it.

L’AVVENTURA (1960) has four main protagonists, three of them humans, but they are dwarfed by Lisca Bianca, a rocky island in the Mediterranean See. A group of wealthy Italians visit the island but when they want to leave, the main character Anna, is missing. Her boyfriend Sandro starts the search, but is soon more interested in Claudia, Anna’s best friend. When they all leave, without having found Anna, Claudia and Sandro are ready to start a new life together. Antonioni is often compared with Brecht. Like the German playwright, he refuses the dramatization of the narrative, because it is a remnant of the bourgeois theatre. Analogue to this comparison, L’Avventura is epic cinema. Brecht’s plays are often transparent, because the actors do not identify with their roles. The audience is not drawn into the play, but left outside to observe. The same goes for Antonioni, because, as Doniol-Valcroze wrote “to direct is to organise time and environment”. Antonioni genius is, that he first introduces time scale and environment, before he develops the narrative, via the actions and words of the protagonists. The breakers on the island, are the real music of the feature. The fragility of the emotions manifests it selves mainly in the way the protagonists talk – but mostly they are on cross purpose. Yet the overall impression is not that of a modern film with sound, but of a very sad silent movie. At Cannes in 1960, the feature was mercilessly jeered at the premiere, but won the Grand Prix nevertheless – a rarity of the jury being ahead of the public.

In LA NOTTE (1960) we observe twenty-four hours in the live of the writer Giovanni and his wife Lydia. Whilst their friend dies in a hospital, they have to accept that their love has been dead for a while. Antonioni uses his characters like figures on a chess board. They are real, but at the same time ghosts. He does not tell their story, but follows their movements from one place to an another. There is no interconnection between them and their environment. They have lost the feeling for themselves, others and the outside. Their world is cold and threatening. Antonioni offers no irony or pity. He is the surgeon at the operating table, and his view is that of the camera: mostly skewed over-head shots. It is impossible to love La Notte. Whilst Antonioni is the first director of the modern era, he is also its most vicious critic.

When L’ECLISSE (1962) starts in the morning, it feels somehow like a continuation of La Notte. Before Vittoria (Vitti) ends her relationship with Francisco, she arranges a new Stilleben behind an empty picture frame. Next stop is Piero (Delon), a stockbroker. Vittoria is like Wenders’ Alice in the City: a child in a world of grown ups, repelled by their emotional coldness. Piero, very much a child of this world, is all calculations and superficiality, his friend’s remark “long live the façade” sums it all up. Long panorama shots show very little empathy with the eternal city, particularly the shots without much noise (music only sets in after the half-way point of the film), are representative of a ghost town populated by little worker ants, dwarfed by the huge buildings. The couple’s last rendezvous is symbolic for everything Antonioni ever wanted to show us: none of the two shows up, we watch the space where they were supposed to meet for several minutes. L’Eclisse will lead without much transition to Deserto Rosso, where Monica Vitti is Guiliana, wandering the streets, getting lost in a fog on a very unlovable planet.

DESERTO ROSSO (1963/4)

Guiliana: “I dreamt, I was laying in my bed, and the bed was moving. And when I looked, I saw that I was sinking in quicksand”. Guiliana’s world is threatening, everything is monstrous, the buildings of an industrious estate are unbelievable tall. The machines in the factories, the steel island in the sea, and the silhouettes of the people surrounding her are enclosing around her. We travel with her from this industrial quarter of Ravenna to Ferrara and Medicina. She is never still, only at the end she is standing still in front of a factory gate. In Deserto Rosso objects become blurred, they seem to be alive, making their way independently. The camera never leaves Guiliana during her nightmare. We see the world through Guiliana’s eyes: “It is, as if I had tears in my eyes”. In the room of his son she sees his toy robot, his eyes alight. She switches it off – but this the only activity she is allowed to master successfully. There is always fog between her and everybody else, even her lover Corrado is “on the other side”. And the fable, which she tells her son Vittorio, who cannot move, before he is suddenly running through the room, lacks anything metaphysical. Roland Barthes called Antonioni “the artist of the body, the opposite of others, who are the priests of art”. For once, Antonioni is one with the body of his protagonist: Guiliana’s body is not one of the many others, she will never get lost.

BLOW UP (1966)

A feature one should only see once – never again. Otherwise one will suffer the same as Thomas photos: Blow Up. Antonioni to Moravia: “All my films before are works of intuition, this one is a work of the head.” Everything is calculated, the incidents are planned, the story is driven by an elaborate design. The drama, which is anything but, is a drama perfectly executed. Herbie Hancock, the Yardbirds, the beat clubs, the marihuana parties, Big Ben and the sports car with radiophone, the Arabs and the nuns, the beatniks on the streets: everything is like swinging London in the 1960ies: a head idea. Blow Up is Antonioni’s most successful feature at the box office – and not one of his best.

ZABRISKIE POINT (1969/70)

Given Cart Blanche by MGM, Antonioni produced a feature in praise of the American Cinema. Zabriskie Point is the birth of the American Cinema from the valley of the Death. Antonioni has to repeat this dream for himself. But he had to invent his own Mount Rushmore, his Monument Valley, to make a film about this country in his own image. A car and a plane meet in the desert. The woman driver and the pilot recognise each other immediately. The copulation in the sand is metaphor for the simultainacy of the act, when longing and fulfilment, greed and satisfaction are superimposed. Then the unbelievable total destruction: the end of civilisation; Antonioni synchronises both events, a miracle of topography and choreography. This is Antonioni’s dream: the birth of a poem.

Both, the TV feature MISTERO Di OBERWLAD (1979) nor IDENTIFICAZIONE DI UNA DONNA (1982) have in any way added something to Antonioni’s masterful oeuvre. The same can be said of his work after he suffered a massive stroke in 1985, leaving him without speech partly paralysation: BEYOND THE CLOUDS (1995), a collaboration with Wim Wenders, and Antonioni’s segment of EROS (2004). AS

A RETROSPECTIVE TAKING PLACE AT THE BFI EARLY IN 2019

Newly restored High Definition (1080p) presentation of the feature, transferred from original film elements by Universal

Newly restored High Definition (1080p) presentation of the feature, transferred from original film elements by Universal