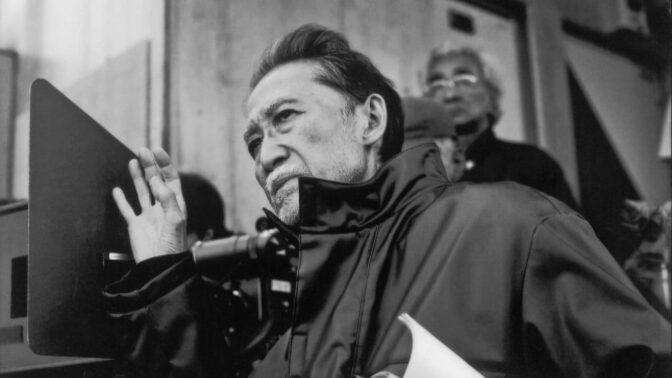

This year’s Viennale Film Festival pays tribute to Vienna’s homegrown star, the actress Helene Thimig, born in Austria when it was still Austria-Hungary.

Helene Thimig (1889-1974), a member of a well‐known Viennese theatrical family, made her debut during the Weimar republic, starring in Gustav Ucicky’s 1932 romantic drama Man Without a Name. Fleeing Nazism with her second husband, the producer Max Reinhardt, he directed her in Franz Werfel’s theatre production The Road of Promise in 1937. They had already met in 1917.

A successful film and stage career followed with performances in around eighteen Hollywood outings. After the war she returned to Vienna to combine work on the stage, cinema and TV both in Austria and Germany until her death at 84.

MAN WITHOUT A NAME (1932) Gustav Ucicky (Austria) ***

Weimar Germany is the setting for this wartime drama, shot in Babelsberg studios and inspired by the Balzac novel Le Colonel Chabert. Helene Thimig plays Eva-Marie, the wife of a successful businessman Heinrich Martin (Werner Krauss) conscripted into the First World War in 1914 where he is reported dead. In actual fact he is merely shell-shocked and reappears years later in 1932, his memory intact, to discover Eva-Marie has re-married his close friend, who has taken over his business. Not Ucicky’s finest film but Thimig gives an impressive performance in her screen debut.

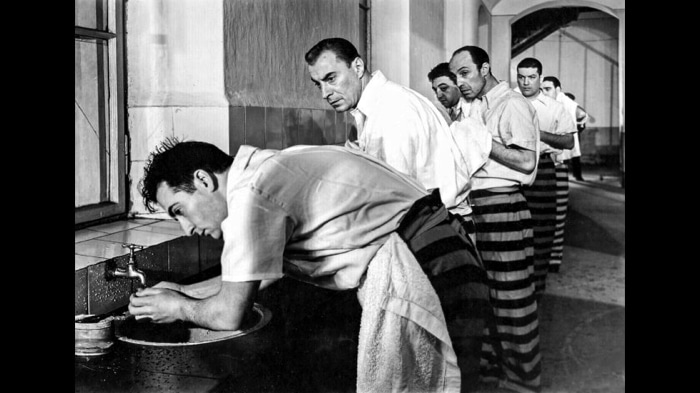

THE HITLER GANG (1943) John Farrow (US) ***

Along with The Great Dictator this gangster film is one of the first biopics about Adolf Hitler, made when he was still alive and kicking. It pictures him as a machiavellian figure determined to thwart other politicians as a means to controlling Germany, setting the seeds of Nazism.

John Farrow directs on a shoe string budget, but none the worse for it. Hitler’s rise to power starts in a military hospital at the end of the Great War, with Germany forced to its knees, and ends on the eve of World War II. The soon to be Fuhrer, played by a spirited Bobby Watson, joins the National Socialist Party infiltrating as an army spy in an ambitious narrative that takes in the Beer Hall Putsch, the writing of Mein Kampf and the burning down of the Reichstag.

The Jews are implicated in Germany’s defeat in the First World War, and although there is no mention of the Death Camps we get a good feel for Hitler’s psychopathic tendencies with the mysterious death of his niece Geli Raubal (played by Poli Dur) leaving us wondering if she actually committed suicide or whether Hitler was responsible. Helene Thimig plays Geli’s mother Angela in a small but not insignificant role. A solid script and decent cast make this worth watching.

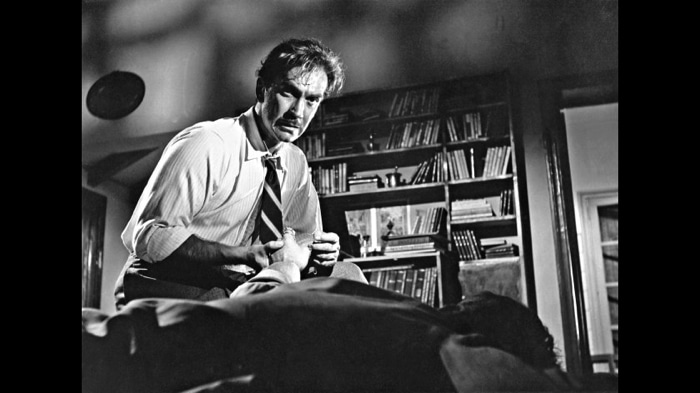

STRANGERS IN THE NIGHT (1944) Anthony Mann (US) ****

Anthony Mann’s B movie runs for just under an hour but packs a palpable head of steam as a 1940s-set feminist psychodrama with timely references to the current social media phenomenon of ‘catfishing’ It’s a jaunty affair that kicks off with William Terry as injured serviceman Johnny Meadows thriving on letters received from an enigmatic ‘Rosemary Blake’. Cut to a hilltop mansion where Helene Thimig is convincing as crippled psycho Hilda Blake doting on a portrait of her (fictitious) daughter Rosemary, and terrorising her put-upon assistant Miss Miller (Barrett), and her new physician Dr Ross (Virginia Grey), a woman she rejects rudely for not being a man.

Thimig really excels in a sinister performance, controlling her submissive friend Ivy and inveigling all around her including Johnny who has made a bee-line to the mansion to find his ‘lover’ Rosemary whose portrait will ultimately provide the gruesome denouement. A really entertaining thriller with gowns by Oscar-nominated Adele Palmer.

ISLE OF THE DEAD (1945) Mark Robson (US) ***

Boris Karloff stars alongside Helene Thimig in this inspired horror outing that derives its eerie atmosphere from the gruesome twosome and Jack MacKenzie’s subtle lighting effects and shadow play. Written and produced by Val Lewton, it sees an international cast (Jason Robards, Ernst Deutch, Ellen Drew) dying one by one while quarantined on a Greek island during the Balkan War of 1912. But Karloff soon discovers the plague isn’t the only danger in this remote outpost. Thimig plays a Greek peasant woman, once again creating a sinister presence as ‘Madame Kyra’ influencing Karloff’s austere but patriotic general into believing that one of their midst is a demon. And it ain’t a man. Gripping stuff despite its 71 minute running time.

THE ANGEL WITH A TRUMPET (1948) 138’ ****

Hartl pulls out all the stops in this gorgeously filmed romantic epic set in the late 19th century, charting the ups and downs of an upper class family of Viennese piano-makers during fifty years (1888-1948).

Often seen as an Austrian national story, the various allegorical aspects are embodied in the characters and the house itself, a classical mansion with the figurine of a trumpeting angel over its front door. The house represents Austria and shots of the little white angel appear at regular intervals reminding that all is well, even when it’s not. There are moonlight scenes, musical interludes, romantic trysts, duels and family gatherings with the men in full military regalia, not to mention flags unfurling against darkening skies, representing the Nazi’s arrival (the with scenes of destruction in wartorn old Vienna. The family will weather all this stoically until the 1940s.

Often drifting into melodrama the 1948 feature is based on the much darker novel of Ernst Lothar who rewrote the book in English while in exile in the US, and this spawned another 1950 outing narrated by Jack Hawkins and starring Wilfrid Hyde-White along with some members of the original cast in minor roles.

Lothar was a great friend of Max Reinhardt, but Hartl’s film is more triumphant and lyrical than the novel and stars Paula Wessely, Maria Schell and Helene Thimig, who once again plays a matriarch. It’s not a significant role but one that offers dignity as the stately chatelaine of the double fronted villa in old Vienna.

The story unfolds from the perspective of Henriette Stein, a Jewish academic (played by Wessely) who has had a ‘light-hearted’ affair with Crown Prinz Rudolf (Fred Liewehr) who then commits suicide at Mayerling. Henriette comes to live in the house when she then marries the piano manufacturer Franz Alt (Attila Horbiger), on the rebound. It’s a marriage of convenience (for her at least) that provides a family. But their union will soon lead to deception, murder and ultimately, death as Austria’s eventful history plays out.

Decision Before Dawn | copyright TCM

DECISION BEFORE DAWN (1951) ****

This spy movie by Anatole Litvak, adapted from George Howe’s novel Call it Treason is not in this year’s Viennale tribute to Helene Thimig, but I thought it was worth including with its eclectic cast and Oscar nomination in 1952 Academy Awards. Thimig plays alongside Hildegard Knef and Dominique Blanchard. According to our critic Richard Chatten, Basehart is top-billed, his observations bookended the film, but the real star is Oskar Werner – beset as usual with doubts – as the ironically nicknamed ‘Happy’.

Like earlier Hollywood productions shot in Germany this goes for a harsh, monochromatic realism. Unlike them, it’s actually set back during the war itself from the point of view of the Germans (most supporting cast consisting of authentic locals, including fleeting glimpses of youthful versions of Klaus Kinks and Gert Frobe) at the point when it had finally sunk in on the majority of them just what a terrible mistake they had made in electing Hitler.

CINEMATOGRAPHY : HELENE THIMIG | VIENNALE FILM FESTIVAL 2024