PE: Well I was born in Lodz (Poland), this is the famous city where the film school was founded and all the time when I was a young boy I was remembering that very special place in the city where all the great directors were learning how to make beautiful films so from the very first moment I was thinking about movies. And then, and this was by accident, my brother gave me a camera and I didn’t think about making stills or even movies at that time, let alone cinematography, but it was such a great pleasure that I decided to go to the film school (which was then funded by the Government) and it all started like that. It you’ve even seen The Promised Land by Wajda, it was filmed in the city of Lodz. It was industrial, full of red brick, dull buildings but the only place that was shining was the film school and that’s why everybody wanted to go there.

Q: Lódz is not only know for the film school but it’s the only city that has a festival aimed at cinematography, the famous Camerimage Festival that takes place each November. Was it natural that you were always going to study there, rather than some other place? Was it because you wanted to follow in the footsteps of Wajda and Polanski?

PE: Well of course, I never imagined that I would go somewhere else, from the very first moment I knew that this was where a young Polish filmmaker should go.

Q: Tell us about the training there and how you ended up working towards cinematography?

PE: Well Lódz was a very special film school. Right from the beginning, we started making a black and white film on 35mm and all the films during my training there were only made on 35mm which was very rare because all the other schools during my training were using 16mm, a smaller camera, so that was the first difference about Lodz. The second was that we had a professional crew; we had gaffers, camera assistants and grips, so from the first year we had to co-operate with those people which was a great training because later on when we started working on professional productions we already had some tricks and knew how to handle the crew, which is one of the most important elements if you’re going to be a good DoP, so we had some great teachers and we made some fantastic friends. So just after film school I started to shoot features with my colleague directors, which was fantastic.

Q So let’s move on now to one of the major collaborators of your career, (Roman Polanski), and it’s somebody who I want to come back to later because this was your international breakthrough.

But first, let’s show a clip of the film you made with Andrzej Wajda, that was the starting point to Hollywood:

[youtube id=”X3T8Gzh-WKE” width=”600″ height=”350″]

ED: Yes, and that’s why I wanted to show you this Pan Tadeusz clip (of the Last Foray in Lithuania (1999)) because it was about the 10th film I did in Poland and probably the one that attracted the attention of Roman Polanski, because after that he called me and asked me to join him in The Pianist (2002) so that was the link between my Polish period of my career and the international one.

Q Before we look at The Pianist I want to find out how exactly you defined your role in the making of all these films. Where you someone who involved yourself very early on with the script-reading with the director and the actors? How did you start to get a vision for the film?

ED: That was the good thing about Lodz film school, we were working most of the time with the directors. After finishing film school I started working with my friend Wladyslaw Pasikowski, I think we’ve made 8 movies together, and the films we made together were like a stylistic breakthrough in Poland and they were very popular. Wladyslaw was like a star. We were working on the script, talking about the locations, scouting together, collaborating on the writing and that tradition is something very special at that school. Together we made Kroll (1991); Pigs (1992); Psy 2: Ostatnia crew (1994); Bitter-Sweet (1999); Demony wojny wed ug Goi (1998); Operacja Samum (1999); Reich (2001); Poklosie (2012).

Q: And does this make things much easier for you when working on the film?

ED: Of course it does: it’s interesting to be involved as early as possible, to know the main subject and the themes to be a part of the whole machinery of the movie-making process, which makes you (as a DoP) more involved and in the centre of the process.

Q: So we come to The Pianist, which won you a César and also the Eagle Polish Film Award 2003 for best cinematography and numerous nominations leading to your becoming Hollywood Cinematographer of the Year in 2005. What were the initial meetings with Polanski like?

ED: Roman is a director who knows exactly what he wants. We didn’t have a long conversation at the beginning, we just met very briefly in Berlin, because that’s where the movie was to be shot, in Berlin and the second part in Warsaw. We were briefly talking about the style of the film and the only thing was said was that it should be as natural and as documentary (in style) as possible and everyday when I went on set I kept in mind that it should be as simple as possible. Because if I can make it like that it will be believable.

[youtube id=”oS-syXeK5Tk” width=”600″ height=”350″]

Q: I mentioned my interest about the relationship between the DoP, the director and the film editor and then tensions between them all. How much did you and Roman Polanski speak about the way you were going to shoot this scene in terms of how it was going to eventually appear with the close screen shots of the actor in the room and then the camera going outside to the streets below?

PE Roman’s way of working is always the same. We don’t know too much about the scenes before we meet with the actors. Every morning there’s a meeting with the DoP, the directors and the actors, we start from scratch with the actors reading the script and he’s (Roman) placing them in the room, in that case. They rehearse the scene over and over again and then after the rehearsals, when everybody knows what they’re doing, we look at the scene created by them and we discuss how to film it. We don’t know what will happen later ’til after the rehearsals and I just love that type of work because everything goes naturally from the script and from the actors.

Q: And is that the way it worked even from the “documentary-type” style you tried to follow in The Pianist?

PE: Yes, nothing is pre-planned, everything seems to be absolutely natural.

Q: So The Pianist led you into Hollywood and how would say that changed things from the point of view of working style? Did you find it more enjoyable, or did you find yourself (being) more of a cog in a large wheel?

PE: Definitely there’s a huge difference between making films in Europe and making them in America. Making films in America you become part of the ‘film industry’, making films in Europe is working with friends, and my friend directors. And this is a totally different type of activity. In the US, you’re part of the big machinery, in Europe you’re working in a creative process with your friends. And that’s always going to be more fun, working with friends.

Q: It’s great that we’ve got two examples of American Film clips to show you and, in a way, you couldn’t get a more different visual style. We’re going to start with All The King’s Men (2006) by Steven Zaillian and the second is Ray (2004) which you made with Taylor Hackford.

[youtube id=”x_WeedShZbs” width=”600″ height=”350″]

[youtube id=”X1rJvSF3l6k” width=”600″ height=”350″]

Q: Ray uses a very soft palette of rich colours, embued with the warm South and reflecting the mellow feel of jazz music but with All The King’s Men you’ve used a very cool steely palate with interesting use of shadow and harsh. Could you talk about how you and Steven Zaillian created the look of this film?

PE: I think the idea was ‘German Expressionist‘ because we all had this picture in our minds on those beautiful black and white films and that’s why we wanted to go with this feel of going away from colour, being de-saturated, not strong and we wanted to use a harder light intentionally to show the hardness and cruelty of that type of politics. Things are a little different now and times have changed and I think the audience likes this type of commercial films rather than the artistic, ambitious type of film.

Q: Just taking that point further, do you think that there’s still a very strong visual culture in Poland? In the UK, I think because we come out of a culture of theatre and writing, there’s a more literary culture but I don’t think there’s ever been a strong visual style here compared to Poland. Is the visual aesthetic still there in contemporary Polish film?

PE: Obviously there’s a huge tradition of classical cinema in Poland and this is Wajda and friends. I was lucky to meet Andrzej and have been with him on many films and he is one of the directors who’s thinking more about the visual side and how the movie will look but I can’t say that this tradition is existing in every single section in Poland. It’s sad but it’s gone. I think that the story has to visible, that’s the most important thing. I wouldn’t like to be remembered as a guy who did good pictures on bad films, I would rather be remembered for good films with bad pictures and I’m being serious (laughs). I’m not fighting for something that’s mine, I’m fighting for the characters, I’m fighting for the scenes, that’s why the composition is good because of something, because of the accent you should put on somebody or some element that should be there and very visible in the film.

Q: So to sum up, looking back over your career so far do you think you have a specific visual style or do you feel your imput is ABSOLUTELY dictated by the material you’re working on?

PE: Yes, as I’m getting older I believe that the script gives all the answers: you just take the script and feel script and smell it…that’s how I think of it. The script dictates the solutions.

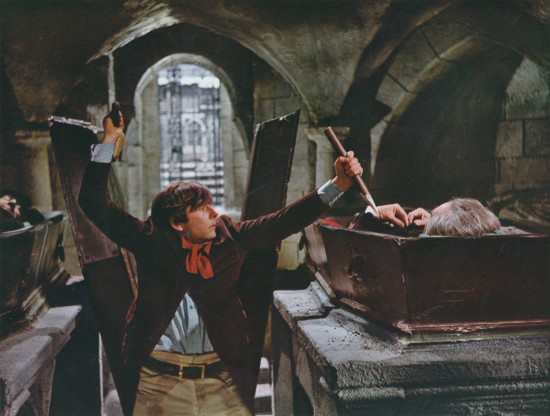

Q: Moving on, let’s talk about Roman Polanski and about the very strong story of your second collaboration with him in 2005, Oliver Twist.

[youtube id=”mCunohBPvGA” width=”600″ height=”350″]

PE: Yes this production had effects that had to be larger than life. We were 90 days shooting this movie in Prague. The costumes were highly exaggerated and we used more make-up on the actors. To create that special look we made use of candle-light, and locally placed lanterns. There were loads of people dragging hundreds of lanterns and different lights around the set just to give the correct feel to the lighting, it was very intense and special.

Q: And moving on to The Ghost Writer (2010) tell us about the way you created the visual look for that film?

PE: There was clouds, and we were waiting for clouds all the time and there was no sunlight or hard light and my goal was to build a contrast, sometimes quite high levels of contrast using only the soft light and also a de-saturated palette of colours.

Q You go from a very short depth of field to a very wide lens in the scene of Ewan McGregor and Olivier Williams when they’re walking along the beach:

[youtube id=”dTe9ExIMciE” width=”600″ height=”350″]

PE: Well this is a different subject: choice of lenses. Roman is using only two lenses, no more. Not everybody know this. For each film we were just picking two lenses and just shooting everything with them. This is very rare.

Q: Why does he do that?

PE: Because he feels that if he switches from long lenses to short lenses for the shot, there will be no consistency for the shot, for the look he’s going for, so in The Pianist we were only using 25 and 32. In Oliver Twist, because of the larger that life idea we were using little lenses like 21 to 25 then for The Ghost Writer we came back to 25 and 32. And nobody else is like that. I’ve never worked with another director who’s so strict, who picks such a small variety of optics.

Q: Let’s look at another clip of The Ghost Writer – one where Ewan McGregor is involved in a car chase.

[youtube id=”Zx4QPwYD0yw” width=”600″ height=”350″]

Q: This is an action sequence. Do you find it pleasurable, upping the ante and working with more dynamic action scenes?

PE: Roman is very precise. Everything grows from the rehearsals, tons of rehearsals, and there’s a little story about this, not about that film but about The Pianist. There is a scene there when 2000 extras are leaving the ghetto and the Germans are putting them into carriages. We had only two days in the schedule to prepare and shoot that scene and it was a complex and very complicated and yet we wanted it to appear very natural. And it was costing tons of money each days with these 2000 extras and on the first day Roman was just rehearsing again and again the producers were going crazy because by the end of the day we hadn’t shot even one metre of film. So on the second day we shot the whole scene very quickly because, after the tons of rehearsals, we know exactly what we wanted. And everything is like that with Roman. Things that appear terrible complex and difficult just seem to be suddenly be so easy and natural and that’s his way of doing complex scenes.

He likes it when the situation is limiting him and when people are difficult and when there’s no time left. At the moment we are shooting Venus In Fur, which is about limitations and only has only two people in real time in the theatre, which is limiting and this is what excites him.

Q: What sort of equipment do you like using?

PE: I think all the cameras are different. I was just used to using Panavision, but for the last 3 or 4 films I was using Arricam which are better and lighter and wellmade and for lens I use Cooks 4. In

Carnage we used 25 and 32.

Q: And how do you capture the feel of a film in the opening scene?

PE: When I’m reading the script for the first time, I try to get a feeling: I’d say I literally smell it – for example no sun, only clouds, black and white, handheld, It’s the basic imagery that comes out from the lines in the script. And as soon as I’ve caught it I start the film and I’m not doing the film until I’ve captured the feel or style of the script because otherwise i don’t know what to do.

Q Have you ever had to compromise your vision to make a film?

PE: My point of view is that the images shouldn’t be beautiful per se. The images have to capture the film, they have to serve the film and it’s not a sacrifice it’s just understanding my work. I don’t think beautiful pics are the best picture, the pics have to serve the general idea and style: handsome or not.

Q Give us an example of where you felt extremely happy with what you’d achieved on a film?

PE: It’s not like that. But there are always mistakes things i’d now in a different way.

Q: Do you prefer working on location or in a studio.

PE: Well on location it’s sometimes easier; you’re there in the surrounding and don’t have to work so hard to imagine the style but and it’s less boring because you’re moving around but on the other hand, the studio gives you the opportunity to control the film and you’re not waiting around for the weather. When I’m sitting around waiting for sun or clouds it’s hopeless and I want to be independent from the weather but then in the studio you always want to be in the other place!

Q: How do you feel about your relationship with editors? It is sometimes difficult?.

PE: I have to say that sometimes I have arguments with editors, especially nowadays (general laughter). Recently I’ve had experiences where they are making decisions about which takes to use; because nowadays everything is transferred on to tape including the take you dont want to use. The editor can choose bad takes that are out of focus or not the ones we chose at the time of shooting. So the editors decisions are technically wrong and I try to explain to them why they’re wrong but they are still going ahead and use the wrong material and it makes me furious. But I’m sure there are still good editors out there (laughs).

Q: Film or digital, which do you prefer?

PE: Yes, all the films so far have been on 35mm. I’ve shot one film on digital and that’s the last Polanski movie, Venus in Fur. Every time, for the last 7 years, before we start the movie we run the tests and all the time the winner was 35mm. And this time we ran the tests and the result came out that new digital Sony F65 was best. Roman and I agreed that this was the one to use for the first time. So we haven’t finished the movie yet and I still have to go through post production. But we’ll see if we’ve made the right decision when I see the final result. Or I’ll be crying (laughs).

Q: Do you find that using digital has effected your performance during the filmmaking process?

Digital is different, I must admit. Looking through the eyepiece used to be the best way to see the filming process but the digital cameras don’t have good eyepieces so you have to look at the shooting process and see the scene is on the monitor which is different, so you don’t operate the camera from the eyepiece anymore. The monitor shows you details, colours, contrast etc so it best to look at that.

Q: Tell us about your relationship with Andrzej Wajda?

PE: We have in Poland since the Second World War, two major film directors: one is Roman Polanski and the other is Andrzej Wajda and I’ve had the luck and the fortune to work with both of them and they’re both completely different, I must say but they are both great Masters: Andrzej is more intuitive and all about the visual side of the film, and his vision because before he was a painter, may be that’s why. Roman is an actor so he knows how to connect with and direct the actors in a very precise way and is very connected to the acting and re-hearsing process. And there is a difference because Andrjez is trying to solve political and social problems but Roman is more interested in telling stories that interest him. But they are both wonderful filmmakers coming from different perspectives.

Q: Do you find your relationship with Andrzej in more intuitive when you’re working with him. Over the last few decades of collaboration, do you find you know what he wants immediately when you start work.

PE: No. With Andrzej every day is an improvisation and completely different. Some days we are working on changes with the script. Others we are implementing these changes with the actors. I never know how it’s going to develop. With Roman, everything is very precise, close to the last detail which I also find very fun and very interesting. I have great pleasure in working with both of them.

Q: We are going to close with a clip from Katyn. Tell us why you want to close with this film.

PE: We wanted to show the mechanism of the crime. There was a great deal of improvision with actors and with the stunts and it was all shot very quickly and shows the cruelty of the situation, filmed with a handheld camera.

Q:Thanks very much Pawel Edelman for talking to us tonight.

PE: Thank you very much.

[youtube id=”_BsC8rOKIng” width=”600″ height=”350″]

PAWEL EDELMAN WAS SPEAKING AT THE BFI ON 14TH MARCH 2013.