Dir.: David Wilkinson; Wri: David Wilkinson, Emlyn Price | Documentary with Philip Rubenstein, Benjamin B. Ferencz, Fritz Bauer, Donald M. Ferencz, Jens Rommel; UK 2021, 175 min.

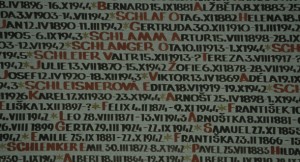

Yorkshire born director David Wilkinson (Postcards from the 48%) has co-written and produced a unique, sober and frightening report on Holocaust murderers that have somehow avoided prosecution. How did it happen? How did the executioners of six million Jews get away it? Only one percent of the million or so perpetrators were actually brought to justice.

On his mission to uncover the truth Wilkinson has travelled the globe interviewing Nazi-hunters and survivors, horrifying clips from the camps underline an utter contempt for retribution that begs the question: what would the US government have done had the Nazis decimated the entire State of Maryland? And how would the British government have reacted had the entire population of Yorkshire lost their lives in the same way? Surely, the rate of successful prosecutions in both cases would have run into double-figures.

The (West) German government and the Allies played their part by turning a blind eye to the atrocities The victors all fell out, starting a Cold War which saw the USA, Great Britain and France freeing already convicted war criminals who would then see active service against the USSR.

From the late 1949 to the mid 1960s the West German government was led by Chancellor Konrad Adenauer, who in 1934 had begged the Nazi Interior Minister Frick to have his state pension restored: “I have always treated the NSDAP properly, against ministerial instructions. I allowed the NSDA to meet in the city sports ground, moreover I allowed the Party to hoist up the Swastika”. His plea was successful. As Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG), Adenauer surrounded himself with a cabinet that included Hans Globke, author or the Nuremberg laws of 1938 for the Nazis. Theodor Oberländer was Minister for Refugees and had been a member of the SA, having participated in the Hitler putsch of 1923, and had been directly involved in the plans to exploit the occupied countries in Eastern Europe. In 1965, Adenauer was replaced by Ludwig Erhard who had the dubious honour of being a member of the Nazi “Arbeitskreis für Aussenwirtschaftsfragen (AAF)” along with Ludger Westrick, Karl Blessing and Hermann Josef Abs. All played a major role both in Nazi Germany and the FRG,

But the government of the time merely reflected the view of the German population: war criminals lived on at liberty, often without having to change their names. Some even returned from exile in South America to bury their dead: Dr. Joseph Mengele, the “Angel of Death” was a prime example, having ‘selected’ Jews on the ramps of Auschwitz for his infamous experiments. Reunited with his family in Switzerland in 1956, he returned to his birthplace in Günzburg/Bavaria in 1959, for his father’s funeral. Everyone in the small town knew that he was present – apart from the police. Mengele died of a stroke swimming in Sao Paulo in 1979, aged sixty-seven.

German justice actually made it extremely difficult for Nazi war criminals to be prosecuted, as Benjamin B. Ferenc, Chief prosecutor of the 1948 trial against the members of the Einsatzgruppen explained: German law did not allow retrospective interpretations of any criminal action, which meant that since it was lawful to kill Jews, Communists, gays and Roma in Nazi Germany, one had to prove the accused acted “in a way beyond the legal (!) requirement” – for example showing more than average brutality or indulging in extra-curricular actions. It was a reasonable defence to clam the Jews were the enemies of Germany. In many trials in Germany and Austria, witnesses were asked for the exact time when the atrocities took place – as if any camp inmate had a watch. Defence lawyers hunted down the witnesses, and the population in many towns joined in.

Thus the trials became more a second punishment for the Jews and other victims, than for the perpetrators themselves. Even though, the names of Fritz Bauer and Jens Rommel, both having been in charge of the Central Agency for the Prosecution of Nazi Criminals in Ludwigsburg, should be mentioned – Bauer gave Mossad a tip-off about Eichmann’s whereabouts in Argentina, because Bauer believed his trial in Germany would not serve justice.

The number of major war criminals who got away it is long: Walter Rauff, who designed the specialised carriages where 100 000 victims met their deaths, fled to Chile, where he died in 1984 aged seventy-seven. Karl Jaeger, Nazi Colonel, carried out the murder of Lithuanian Jews, his diary showed that he killed over 100,000 men and women, of which 4273 were children. In the 1965 Sobibor trail in Germany, the main defendant Alfred Ittner was convicted of the murder of 68 000 Jews – his punishment was seven years in prison. Johanna Altvater, a mere secretary, killed Jewish babies by throwing them out of the window. She was never prosecuted and died aged at the ripe old age on 84, in 2003.

Dr Herta Oberweiler was responsible for the deaths of thousands of children who lost their lives as a result of her sepsis “research’. She was sentenced to twenty years prison, later reduced to five. After her release, she actually got her licence back, and it took years for her to struck off the register. Alois Brunner, Eichmann’s deputy, responsible for the murder of over 100,000 Jews, got the death penalty in absentia in France, but fled to Syria, where he advised the government on torture methods, dying in his late 90s. Herberts Cukurs, the “Butcher of Riga”, was not so lucky. He was responsible for killing 30 000 Latvian Jews. In a macabre incident, Cukurs asked an old Jewish man to rape a young Jewish woman, and then shot all Jews who looked away. He fled to Brazil, where he was killed by Mossad agents in 1965, aged sixty-four. But in 2014, a musical was produced in his home town, showing him as a hero.

The British government’s role in all this is rather shameful. Foreign Secretary Sir Anthony Eden was asked by the Bulgarian government in the early 1940s, to allow over ten thousand Jews, threatened by the Germans, to emigrate to the British Protectorate of Palestine. Eden refused, and all Bulgarian Jews were murdered subsequently in Treblinka. Later, the UK Government clamed to be too broke, to contribute to the 1948 trial against members of the murderous Einsatzgruppen. Even though the trial went ahead, few of Einsatzgruppen were prosecuted. After the war, the UK became a safe heaven for Nazi war criminals; and Wilkinson visits places in Oldham and Selby, were many had hidden, a map showing that the perpetrators managed to settle throughout the UK. Philip Rubenstein, former director of the All Party Parliamentary War Crime Group was instrumental in changing the law to allow for Nazi prosecution in the UK. He reports, that since 1943 Civil Servants were actively employed in avoiding Nazi prosecution, claiming that it “smelled of laws made by the victors.” Needless to say, the Holocaust is not on the main curriculum in UK schools.

GETTING AWAY WITH MURDER(S) is an epochal work, much more than a feature documentary, it is disturbing testament to widespread genocide and asks grave questions of our judicial system AS

Critically-acclaimed Holocaust documentary Getting Away with Murder(s) to be made available to view for free as a two-parter to mark Holocaust Memorial Day

27 January 2023 | 9pm CHANNEL4

Director Stanley Kramer (1913-2001) was always ready to bring controversial stories to the screen, Guess Who is Coming to Dinner being one of them. When he directed Aby Mann’s adaption of his own story in 1961, Judgement at Nuremberg was very much a slap in the face for Cold War warriors, who had forgiven (West) Germans the Holocaust, just to have old Nazis to fight against Bolshevism.

Director Stanley Kramer (1913-2001) was always ready to bring controversial stories to the screen, Guess Who is Coming to Dinner being one of them. When he directed Aby Mann’s adaption of his own story in 1961, Judgement at Nuremberg was very much a slap in the face for Cold War warriors, who had forgiven (West) Germans the Holocaust, just to have old Nazis to fight against Bolshevism. Eduard falls in love with social climber Lucie (Rasenack), who runs a brothel and talks him into joining the SA. Back in the village, another member of the Simon clan is imprisoned in a KZ, for his Communist Party leanings. Maria has now fallen in love with the engineer Otto Wohlleben, but a letter from Paul, who is living in the USA, destroys any future for them. When Paul finally remerges, arriving in Hamburg, he cannot enter the country due to to his name being misconstrued as being ‘Jewish’ – and he has no proof of his Aryan ancestry. Meanwhile Otto is defusing bombs at the front when he learns that Maria has borne him a son called Hermann who he will meet for the first time at the end of the war, when American troops arrive in the village, after the Allies’ victory in 1945, bringing with them a sense of normality – and food. Paul finally returns from the USA, his big limousine is the talk of the village. But his return is not celebrated by everyone and he soon goes back, missing the funeral of his grandmother Katherinna (Bredel). Maria lives her life through her son Hermann who is interested in music and poetry. He eventually falls for Klärchen, who is eleven years older than him. Paul has since sold his company to the Americans for a huge profit, and channels his success into helping Herman with his musical career.

Eduard falls in love with social climber Lucie (Rasenack), who runs a brothel and talks him into joining the SA. Back in the village, another member of the Simon clan is imprisoned in a KZ, for his Communist Party leanings. Maria has now fallen in love with the engineer Otto Wohlleben, but a letter from Paul, who is living in the USA, destroys any future for them. When Paul finally remerges, arriving in Hamburg, he cannot enter the country due to to his name being misconstrued as being ‘Jewish’ – and he has no proof of his Aryan ancestry. Meanwhile Otto is defusing bombs at the front when he learns that Maria has borne him a son called Hermann who he will meet for the first time at the end of the war, when American troops arrive in the village, after the Allies’ victory in 1945, bringing with them a sense of normality – and food. Paul finally returns from the USA, his big limousine is the talk of the village. But his return is not celebrated by everyone and he soon goes back, missing the funeral of his grandmother Katherinna (Bredel). Maria lives her life through her son Hermann who is interested in music and poetry. He eventually falls for Klärchen, who is eleven years older than him. Paul has since sold his company to the Americans for a huge profit, and channels his success into helping Herman with his musical career. The shoot ran from 1981, and took 18 months, before 13 months of editing resulted in a 15-hour potted version, down from 18 hours of rough-cut. Over ten million West Germans watched the eleven episodes. Thanks to DoP Gernot Roll, a later cinema version was internationally successful, the seemingly arbitrary changes from colour to black-and-white and back giving the chronicle of the years between 1919 and 1982 an added feature. The main premise of HEIMAT was to show how ordinary people – in this case the Germans – can easily embrace a murderous regime such as Nazism, and even in a small village like Schabbach, could tolerate the existence of the concentration camps, almost turning a blind eye. These same people went on to embrace consumerism, this time following in the footsteps of the Americans. Reitz would follow Heimat with The Second Heimat (1992), Heimat – Fragments – The Story of the Women in Heimat (2006) and Home from Home (2013) – all together another 30 hours viewing, premiered at the Venice Film Festival, which became Reitz’ second home.

The shoot ran from 1981, and took 18 months, before 13 months of editing resulted in a 15-hour potted version, down from 18 hours of rough-cut. Over ten million West Germans watched the eleven episodes. Thanks to DoP Gernot Roll, a later cinema version was internationally successful, the seemingly arbitrary changes from colour to black-and-white and back giving the chronicle of the years between 1919 and 1982 an added feature. The main premise of HEIMAT was to show how ordinary people – in this case the Germans – can easily embrace a murderous regime such as Nazism, and even in a small village like Schabbach, could tolerate the existence of the concentration camps, almost turning a blind eye. These same people went on to embrace consumerism, this time following in the footsteps of the Americans. Reitz would follow Heimat with The Second Heimat (1992), Heimat – Fragments – The Story of the Women in Heimat (2006) and Home from Home (2013) – all together another 30 hours viewing, premiered at the Venice Film Festival, which became Reitz’ second home.