In celebration of the 100th anniversary of the independence of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia, this year’s Karlovy Vary festival has put together an extensive retrospective of poetic documentary films from the Baltic region. This collection of important works of the “Baltic New Wave” dating back to the early 1960s features the world premiere of Bridges of Time, a new documentary by renowned Lithuanian filmmaker Audrius Stonys and his Latvian colleague Kristine Briede.

The section Reflections of Time: Baltic Poetic Documentary, which will consist of six blocks of short- and medium-length films and two feature-length documentaries, represents a rare opportunity to see key works of documentary film from the Baltic countries within the context of films made in neighbouring countries. “Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia share with the former Czechoslovakia not just the year in which they declared their independence, but also an exceptionally artistic outpouring of cinematic production in the 1960s.

In the 1960s, Baltic documentary film underwent a narrative and aesthetic transformation. The works of the new generation of filmmakers contrasted with the earlier approach to documentary films, and this Renaissance in Baltic documentary film reflected worldwide changes in how documentaries were made. The newly created films were characterized by a sensitivity towards the story and the chosen subjects. They were based more on the image as such, and explored the possibilities of the wide-screen format, editing, unusual combinations of sound and image, working with time and space, and sometimes also staged re-enactments. These filmmakers were inspired by the legends of documentary film such as Dziga Vertov, but also by the latest trends of cinéma-vérité or direct cinema.

Among the documentaries in the retrospective are films by Latvian directors Ivars Kraulītis (his canonical 1961 short film White Bells), Aivars Freimanis and Herz Frank (the legendary 1978 film Ten Minutes Older, an intimate portrait of a boy watching a puppet theatre consisting of a single ten-minute shot). One of the early pioneers of the new cinematic style, Uldis Brauns, will be represented by his grand feature film 235,000,000(1967), which shows the life of people and important events in the Soviet Union.

Lithuania is represented by two award-wining documentaries by Robertas Verba, the founding father of Lithuanian poetic documentary film and the country’s most distinctive documentary filmmaker. The Old Man and the Land (1965) and The Dreams of the Centenarians (1969) both immortalize the ancient inhabitants of the Lithuanian countryside. Other Lithuanian films include Henrikas Šablevičius’s A Trip Across Misty Meadows (1973), which takes the viewer on a journey across the traditional Lithuanian landscape, and Apolinaras (1973), a film about an eccentric guardian of the law who, like Verba’s old men, is far removed from Soviet reality.

Estonia’s stylistically diverse documentary cinema, whose main focus was not only on village life, but to a large extent also on the city, is represented by films by Andres Sööt (The 511 Best Photographs of Mars, 1968, which combines real and imaginary states and experiments with a hidden camera), Ülo Tambek (Peasants, 1969, which spent 20 years locked in the vaults for its critical view of the Soviet system) and Mark Soosaar (The Woman of Kihnu, 1974, an anthropological observational documentary).

The section also presents the newest generation of filmmakers who began to work during the collapse of the Soviet Union and whose poetic style was significantly influenced by the New Wave of Baltic documentary film. Lithuanian documentarian Audrius Stonys will presents his film The Land of the Blind (1992), which earned him the European Film Academy’s Phoenix Award for Best Documentary Film, and also his later Anti-Gravitation (1995). We will also be showing renowned Latvian director Laila Pakalniņa’s trilogy The Linen, The Ferry and The Mail (1991–95), which launched her international film career (The Ferry and The Mail were screened as part of the Un Certain Regard section at the Cannes Film Festival).

The section also presents the newest generation of filmmakers who began to work during the collapse of the Soviet Union and whose poetic style was significantly influenced by the New Wave of Baltic documentary film. Lithuanian documentarian Audrius Stonys will presents his film The Land of the Blind (1992), which earned him the European Film Academy’s Phoenix Award for Best Documentary Film, and also his later Anti-Gravitation (1995). We will also be showing renowned Latvian director Laila Pakalniņa’s trilogy The Linen, The Ferry and The Mail (1991–95), which launched her international film career (The Ferry and The Mail were screened as part of the Un Certain Regard section at the Cannes Film Festival).

The retrospective’s highlight is Bridges of Time, a remarkable metaphysical essay by renowned Lithuanian filmmaker Audrius Stonys and his Latvian colleague Kristine Briede – an untraditional look at the generation of filmmakers of the “Baltic New Wave” and a meditation on the ontology of documentary film. “Baltic poetic documentary cinema created an independent world, free from soviet ideology, lie and propaganda. It was a declaration of inner freedom. The black and white world of poetic documentary films was full of colours. Sadness was full of joy. And joy was touched by deep existential sadness. These films reminded us about the very core of cinema—to film and to enjoy the beauty of the leaves, moving in the wind.” adds Audrius Stonys. The film’s presentation at Karlovy Vary will be its world premiere.

KARLOVY VARY FILM FESTIVAL | Czech Republic | 29 JUNE – 7 JULY 2018

The section also presents the newest generation of filmmakers who began to work during the collapse of the Soviet Union and whose poetic style was significantly influenced by the New Wave of Baltic documentary film. Lithuanian documentarian Audrius Stonys will presents his film The Land of the Blind (1992), which earned him the European Film Academy’s Phoenix Award for Best Documentary Film, and also his later Anti-Gravitation (1995). We will also be showing renowned Latvian director Laila Pakalniņa’s trilogy The Linen, The Ferry and The Mail (1991–95), which launched her international film career (The Ferry and The Mail were screened as part of the Un Certain Regard section at the Cannes Film Festival).

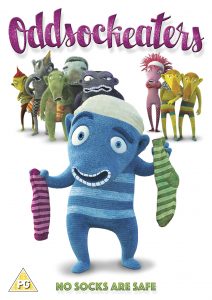

The section also presents the newest generation of filmmakers who began to work during the collapse of the Soviet Union and whose poetic style was significantly influenced by the New Wave of Baltic documentary film. Lithuanian documentarian Audrius Stonys will presents his film The Land of the Blind (1992), which earned him the European Film Academy’s Phoenix Award for Best Documentary Film, and also his later Anti-Gravitation (1995). We will also be showing renowned Latvian director Laila Pakalniņa’s trilogy The Linen, The Ferry and The Mail (1991–95), which launched her international film career (The Ferry and The Mail were screened as part of the Un Certain Regard section at the Cannes Film Festival). Wri/Dir: Galina Miklinova | Animation | Czech Rep | 83′

Wri/Dir: Galina Miklinova | Animation | Czech Rep | 83′