Barnaby Southcombe’s directorial debut, I, Anna, was released in cinemas last December, with advance showings at the BFI London Film Festival. Now, ahead of the film’s DVD release – on April 8 – we were fortunate enough to speak to man himself about his dark and delectable film noir which stars Charlotte Rampling and Gabriel Byrne, the former of which is the filmmaker’s very own mother.

[youtube id=”up2gf6vQRD8″ width=”600″ height=”350″]

We’re now in the wake of your first ever theatrical release – how has the whole experience been? Noticed any dramatic changes in your life since I, Anna came into it?

BS: [Laughs] It’s been an amazing journey to be honest, and not one that I ever quite expected it to be. I think, a bit like your first girlfriend, it’s going to be a voyage of discovery. You know, with releasing a film and it coming out and getting good reviews and some very vitriolic stuff as well, so it’s quite a thing to get your head around, then with the release of the film some reviews that were a lot better and you just understand that the people feel very differently and very passionately about film in a way that, you know, you and I do. We feel very strongly about the films that we like and also the ones that we dislike, so it’s just getting to grips with being on the end of that is a novel one, and that’s come around and it feels like now I’m doing this part of the journey with the DVD release: it’s coming to terms to feeling a bit more acceptant about that. So yeah, it’s good, and very keen to move on now. I’ve followed the film – and it’s still out theatrically and it will be until the end of March in various locations in the UK. I’ve been following it and introducing it and talking with people, so it’s been really good having made the film to see who and where it’s connecting with, and how it’s connecting.

Q: You’ve toured the world with this film having done the festival circuit – that must have been a really fun experience, particularly in seeing how different audiences react to the film?

BS: Absolutely. As you say, it started off with this incredible round of festivals that it did and to see it play in China to what I assumed would be a very small, ex-pat community, but you know, there wasn’t one white person in the cinema and very few of them spoke English, so God knows what the translation was, but there was just this kind of sign-language understanding of appreciation of the film afterwards which was kind of extraordinary, and the same in Russia and stuff. That’s the beauty of the film, is to be able to travel.

Q: The film is certainly influenced by world cinema, with Nordic noir and also the likes of François Truffaut and Jean-Pierre Melville too. Do you think such cultured influences helped in connecting with a worldwide audience?

BS: I dunno, it’s a personal thing isn’t it? I guess what you try and do is feed in to a consciousness of film and then hopefully you bring a new element to it, so you’ve got something which people can relate to: a kind of languid, formal, quite architecturally-framed film, as you say, from Melville and Truffaut, then you add what I felt was this British quality to it. You bring those things together and hopefully you have something fresh but feels familiar at the same time. It has gone down well, it was very well-received in Sydney for example, so yes, in effect, I think that it does help. But it’s difficult, I mean, what did you think of The Master?

Q: I loved it – thought it was great.

BS: It’s a difficult one to get though isn’t it? It’s not an easy one, because you’ve got no frame of reference for it. You’re looking at something which is pretty startling and new, and I think it will outlive us all as a result. It’s not the easiest one to get.

Q: In terms of adding a British quality to the film, the original story this is based on was set in America, so was moving it to London a conscious decision, or more logistical?

BS: A conscious one. I liked the premise of the novel and I liked that it was very much about this woman in a very particular time in her life, a very fragile and delicate time in her life and I found that very interesting. Then there’s this cop who becomes involved with this woman, who may or may not have committed a crime. In New York it felt like it had been very well explored and done by far bigger directors, so right from the start I wanted to give it a European flavour and bringing it to London would add that element, this new, fresh element and also keep this European flavour that I was quite keen on.

Q: What do you think it was that attracted you to this story of an older woman?

BS: Very much her. I just found her fascinating, I found these small, emotional journeys that are actually quite epic in their courage and what they have to achieve. Small things that, to the person, becomes these mountains to climb. This idea of being shelved at a certain age, that the rug is pulled from beneath your feet. You feel that you’ve paid your dues, you’ve done everything right and you feel like you can settle, and then bang, you’re thrust out into the world to find yourself again and define yourself through other people’s eyes, and I think that is a kind of scary thing to do and place to be. I don’t see a lot of that in cinema and I felt that it was something I wanted to explore, so I really connected with this older woman I guess. Also the guy as well, that’s what I liked about it, I liked these characters who have so much to give and are definitely more interesting given their life experience, and yet find it more difficult to connect and find companionship.

Q: Did you instantly think about casting your mother – Charlotte Rampling – for the lead role?

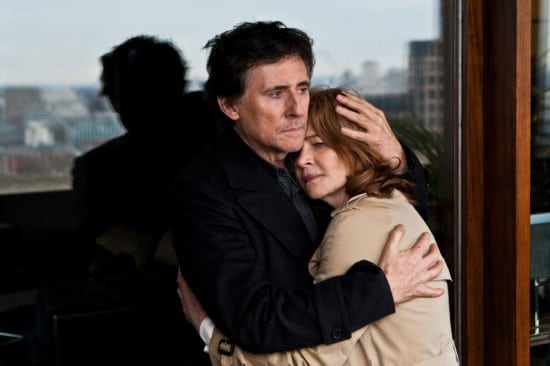

BS: It was a lightning bolt for me. I was given the novel by my producer at the time and we were developing something completely different, a teen drama, and we were struggling with the script and he told me about this book he remembered from when he was a teenager that created quite a stir in Germany and told me to have a read to see if it still stands up, and it was very much that, it just seemed absolutely right for her and no-one else. To a certain extent, when I started writing, Gabriel Byrne was the same, I wrote it with both of them in my head, I could hear their voices when writing, and that was the one compromise I wouldn’t make – those two or nothing. I really felt that I hadn’t seen that cinematic pairing and I just knew the chemistry would be great and it was something I wanted to see as a viewer so that was just one thing I wouldn’t have done any other way.

Q: Considering this is your debut feature film, how helpful was it to have people as experienced and talented as Charlotte and Gabriel on set?

BS: Oh it all makes all the difference, it defines us. I have worked a lot on television and worked with some fantastic crews, but I made a conscious decision to work with a new crew. Not because I was unhappy with anyone else but I wanted people to have more film experience than I had and I wanted people to really understand the differences and language more than I would. My editor had edited The Hours, and a number of highly-acclaimed, big feature films, and worked with great directors. Everyone really had a lot of experience, and down to the actors who you know are just going to give you so much, the smallest scene becomes this little jewell of a moment, it makes all the difference.

Q: So what was the dynamic like in directing your own mother? Is it quite comforting to have her around, and is it difficult to avoid calling her ‘mum’ and maintain a level of professionalism?

BS: Yeah that was the hardest thing, I kind of made a decision I wasn’t going to call her mum on-set, although a lot of the crew would just come up to me and say “Oh yeah your mum wants to know when you’re going to be ready”, so that was the only thing I felt that I needed to exert some sort of authority, but actually it was a very natural, very comfortable environment and one that I would certainly repeat if the subject matter was right. You know she dragged me round a lot of film sets when I was a kid so I’ve always had a fascination for film, so of all the kids, I was the one who lurked around her film sets the most, so I’ve always been hanging around, so she’s used to having me around, so it was just a nice environment. She wouldn’t necessarily race off back to her trailer as soon as we said cut, she would be hanging around on set, it just makes for a good, kind of gypsy caravan type of feeling and environment.

Q: There is a real vulnerability to the character of Anna and that was enhanced by the fact she had a broken wrist – but am I right in thinking that wasn’t a deliberate move, she actually did fracture her wrist?

BS: Yeah [laughs[ she did. About three or four days before the shoot which was an absolute catastrophe at the time, for her and for me. Having spent so long and having got this far without having had to compromise too much and then suddenly have this thing which just seemed ridiculous and completely out of the blue was something that was tough to deal with. So we explored the possibility of claiming on insurance – and we had a very valid claim – and we could have put it off, but we couldn’t really put it off for very long because Gabriel’s availability disappeared and he went off to two very long engagements, and with the film industry being the precarious house of cards that it is, there was a great risk of the film not being able to come back together so we had to make a decision as to whether we were going to find a way around this or let the whole thing go – so I spent a few days with the script and came to what ultimately I felt was a really interesting development and one that I had to hit myself for not having thought of before. Because as you say, it’s a very strange place to injure yourself to that extent and not know how you did it, and without any kind of words it becomes a very unsettling place to be for somebody and I thought that was quite effective. It was also a very clear metaphor as well of suppression, that this thing is itching away underneath and bursting, trying to get out – like the memories of the murder that she is suppressing. So it seemed to work very well in the end – so it’s a happy accident.

Q: To add to Anna’s vulnerability, there was a very voyeuristic camerawork that would follow her around as though following a man’s gaze – can you tell us about that approach and what you felt it brings to the film?

BS: Again that is very classic noir, the idea of the male gaze, and the male gaze being that of a police detective, and that’s one that fits into a very comfortable, familiar stereotype of filmmaking and the idea was to try and find ways to evolve and to work around that and to have a different kind of relationship, one that starts off as a voyeuristic one but then ultimately develops as one of connection and empathy, opposed to one of lust and obsession.

Q: You were filming on location at the Barbican, why that particular setting?

BS: I didn’t want it to be a familiar side of London, I wanted the feeling I had when I first came to London. I didn’t grow up in London, I grew up in France and I went to school in France, and I came to University here and it felt very overwhelming, the city felt so much bigger than what I knew, and it was kind of unforbidding. Although most of London is, architecturally, very small and terraced houses, the feeling of it is much more smaller and forbidding than it looks and I really wanted to capture that feeling, that feeling how in the city of London, what are the chances of two people actually meeting? Two people who are right for each other? So I was looking for an environment that would stand out and would fit into a slightly out-of-time feeling and these two characters are kind of stuck in time, they are stuck a few years back and haven’t really been able to move on, so I wanted everything to feel out-of-time to a certain extend. It’s very much a contemporary film, but all the locations just don’t quite feel of this era, and the Barbican really fitted that bill perfectly. Also, just on a geeky level, there had been a 10-year shooting ban in the Barbican, so it’s not the most familiar of cinematic landmarks and I liked the fact that we were one of the first crews to be allowed back into the Barbican to shoot.

Q: Having mentioned before that you’ve grown up around the industry and spent time on film sets as a child, do you think that that insight has inherently given you a deeper knowledge of how the whole industry works, and has put you in good stead now as a filmmaker?

BS: It’s too early to say. I mean, let’s see how I get on. The film thing is somewhere I’d like to stay, certainly for a while, and let’s see if I’m allowed to. It feels like a comfortable environment, whether that’s successful or not I don’t know. Time will tell.

Q: Is this what you’ve always to do though? Had you ever contemplated a career outside of filmmaking?

BS: Um, not really. It’s been a long road to filming though, that’s for sure. I’ve worked in TV a lot, and I was always interested in that. The directing thing came on a little bit later, after school basically. I was quite into theatre when I was in school, but then when I went to University I discovered directing and I found working with actors more rewarding than being an actor.

Q: So finally, what have you got planned next? Are you working on anything at the moment?

BS: I’m actively working with some really exciting, new, young writers – a playwright and also a filmmaker whose script I’m working on. I’m absolutely developing stuff that isn’t quite ready to go yet, but the last few months have been a very creative time in development, so I’m hoping I’ll be able to announce something soon – but I’m not quite ready to do that. SP

February 2013. I, ANNA IS OUT ON DVD FROM 8TH APRIL 2013 COURTESY OF AMAZON AND CURZON ARTIFICIAL EYE.

[youtube id=”LItOHqYys10″ width=”600″ height=”350″]