Dir: David Secter | Canada, drama 81′

The making of a positive gay film in Canada during 1965, before the legalisation of gay sex in 1969, would be a difficult proposition and a restored print of Winter Kept us Warm demonstrates in hindsight how this can work in the film’s favour.

Directed by David Secter as a student-funded production, the film avoids studio-based filmmaking in favour of natural settings, and reflects the influence of the 1960’s European new wave, containing an authentic jazz soundtrack, and name checks contemporary cultural references including Harry Belafonte and Miriam Makeba.

Still photographic images punctuate scenes involving black/white and grey-toned lighting. These are moody and grainy enough to feel like the cinema verité improvisation of John Cassavetes. Actors appear to be untrained providing a non-professional, at times naïve energy.

The film focuses on the relationship of two young male university students where explorations of the possibilities of sexuality are not always clear outside heterosexual role models. Peter (Henry Tarvainen) arrives at University by car during a lengthy credit title sequence, and starts to find his feet as a freshman. Sensitive by nature and the source of a bully incident, he gradually becomes the focus of interest for second-year student Doug (John Labow).

The dialogue is loaded with, at times, humorous and boyish camp innuendo while naked communal showers and fooling about in a sauna foster relaxed affection between the men. Doug develops deeper feelings for Peter which collide with how both are expected to handle interest in girls. The film suggests that the relationship is the right connection at the wrong time and one will draw back and reject the feelings of the other.

Touching on gay identity issues as far as would be possible in 1965, the film is based on a semi-autobiographical incident. A line of dialogue begins to question the friendship of the two men but even the love that dare not speak its name is not to be fully spoken.

Basil Dearden had also used social repression at the time of Victim in 1961 revealing how the pressure of gay identity during times when freedoms are restricted can both shape and define the trajectory of a film. Whether conscious or not, the film suggests that the lack of gender role models can be inhibiting, making Winter Kept us Warm far more interesting than it first appears.

Although the film leaves its central premise only partly resolved, it can be seen to do so in a way that is accurate and honest with regards as to how sexual identity evolves. The other element that works in its favour is the architecture of the Sir Daniel Wilson Residence at The University of Toronto. This is an early 1950s-built campus for male students featured in almost every scene throughout seasons of the year. The gothic revival style of architecture acts as an enclosed boundary, echoing the brief flowering of a relationship that just might bud but has little chance to survive in the wider world that awaits outside. The film was Canada’s entry at the 1965 Cannes Film Festival. @PeterHerbert

SCREENING DURING BFI FLARE FILM FESTIVAL 2025 |

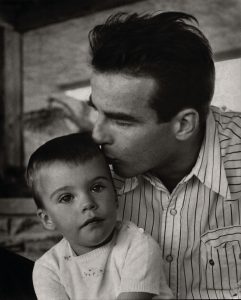

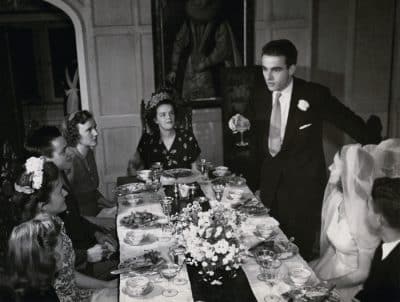

Co-directing and narrating this eye-opening documentary, Robert Clift (who never knew Monty) digs into a treasure trove of family archives and memorabilia (Brooks recorded everything) to reveal an affectionate, fun-loving talent who loved men and dated and lived with women, according to close friends. Monty chose his roles carefully during the ’40s and ’50s, declining to sign a contract to retain complete artistic independence from the studio system with the ability to pick and chose, and re-write his dialogue. This freedom also enabled him to keep much of his private life out of the headlines, although his memory was eventually sullied by tabloid melodrama with his untimely death at only 45. His acting ability and dazzling looks certainly gained him a place in the Hollywood firmament with a select filmography of just 20 features, four of them Oscar-nominated.

Co-directing and narrating this eye-opening documentary, Robert Clift (who never knew Monty) digs into a treasure trove of family archives and memorabilia (Brooks recorded everything) to reveal an affectionate, fun-loving talent who loved men and dated and lived with women, according to close friends. Monty chose his roles carefully during the ’40s and ’50s, declining to sign a contract to retain complete artistic independence from the studio system with the ability to pick and chose, and re-write his dialogue. This freedom also enabled him to keep much of his private life out of the headlines, although his memory was eventually sullied by tabloid melodrama with his untimely death at only 45. His acting ability and dazzling looks certainly gained him a place in the Hollywood firmament with a select filmography of just 20 features, four of them Oscar-nominated. Particularly interesting are Brooks’ conversations with Patricia Bosworth, one of the film’s talking heads and the author of a 1978 biography of Clift that inspired later biographies, but has so far become the accepted version of events, although she apparently got many details wrong and certainly lost out to Jenny Balaban in the Monty relationship stakes, when Barney Balaban (President of Paramount) invited the young actor to join them on a family holiday. He is seen messing around on the beach where he cuts a dash with his good looks and exuberance.

Particularly interesting are Brooks’ conversations with Patricia Bosworth, one of the film’s talking heads and the author of a 1978 biography of Clift that inspired later biographies, but has so far become the accepted version of events, although she apparently got many details wrong and certainly lost out to Jenny Balaban in the Monty relationship stakes, when Barney Balaban (President of Paramount) invited the young actor to join them on a family holiday. He is seen messing around on the beach where he cuts a dash with his good looks and exuberance.