Dir: Virpi Suutari | Finland, Doc 103min

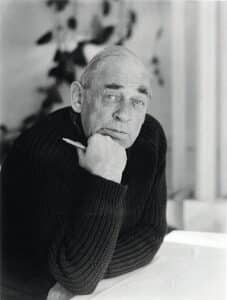

This comprehensive biopic about one of the greatest designers of the 20th century is both an affectionate tribute to the work of Finnish architect Alvar Aalto and a touching love story. Hugo Alvar Henrik Aalto (1898-1976) and his architect wife Aino Aalto shaped the modern world of design through their cutting edge buildings, furniture, textiles and glassware in much the same way as America’s Charles and Ray Eames and even Britain’s Terence Conran.

Virpi Suutari digs deeps into the archives with her writer and award-winning editor Jussi Rautaniemi (The Happiest Day in The Life of Olli Maki) to take us on a cinematic journey into life of a man whose designs were boosted by rapid economic growth in Finland and encompassed the lofty Finlandia Hall in Helsinki and the practical Paimio Sanatorium. For over five decades, from 1925-1978, the Aalto modernist aesthetic gave rise to iconic creations such as the Beehive light-fitting (1959), and the 406 armchair (1939) which remain essential style markers for the conoscenti. And even if you couldn’t afford a house designed by the Finnish luminary you could at least have one of his curvy Savoy vases (inspired by a Sami woman’s dress). These timeless modern creations could be made on an industrial scale but still retained a sense of simple luxury rooted in Finnish heritage from sustainable local materials such as birch wood, and glass blown in the littala factory.

Finnish documentarian Virpi Suutari shows how Alvar and Aino were not only talented architects but also a popular and cosmopolitan couple whose designs would become classics, defined by their practicality and precision. The Savoy vase won the Karhula-littala design competition in 1936 and would go on to be an iconic and elegant everyday item.

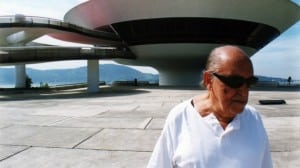

The film then travels further afield to show how Aalto’s civic and private buildings have stood the test of time and still associate well with their natural environment, from the private Villa Mairea in the late 1930s, to a university in Massachusetts, a pavilion at Venice Biennale and an art collector’s house near Paris, these were not ‘starchitect’ projects sticking out of the places surrounding them, but elegant and practical “machines for living” that provided for every eventuality. Aino and Alvar co-founded their furniture design company Artek in 1935, Aino becoming its first design director with a creative output that included textiles, lamps and interior design with clear and simply style, and this made way for complete design package, from lighting to door handles.

Opting for a straightforward chronicle approach Suutari shows how Aalto first set up a practice in his home town of Jyväsikylä in 1921 working on schemes that followed the predominant Nordic classism of the time. Meeting and marrying Aino Marsio in 1925 was the turning point, personally and stylistically, and after the birth Johanna later in 1925 (son Hamilkar would arrive three years later) the couple set off for Europe to discover the Modernist International style. But the groundwork for the practice was founded in Functionalism, and the Paimio tuberculosis sanatorium (1929-1933) was precisely that – providing a user-friendly and practical solution to healthcare (Aalto also designed most of the furniture with the famous Paimio chair devised to assist patients’ breathing).

From then on designs became more fluid with the increased use of natural materials and spatial awareness. The concept once again went from the outside inwards, with interiors and even small details such as fixtures and fittings all forming part of a cohesive aesthetic. One of Aalto’s main achievements was the invention of the L-leg system that enabled legs to be attached directly to the table, he also pioneered the practice of bending and splicing wood, leading to the curved look of the tables and stools. This also meant that furniture could be created on an industrial scale, through defined product lines that were also patented.

Aino and Alvar enjoyed a close partnership in work and in love, with Aino’s travels to source ideas for Artek often taking her away from home until her early death from cancer in 1949. During these times apart the couple kept in touch by a constant of letters, and these epistolary exchanges are woven into the narrative expressing a certain freedom that hints at an open marriage but also a healthy flexibility that helped to keep their relationship alive, according to Suutari’s take on events. This is a love story that brims with positive vibes, and clearly the couple drew contentment and creative energy from their secure family life and love for their children.

After Aino’s death, Alvar was not to be alone for long, he soon married young architect Elissa Makiniemi and the couple would go on to design a villa just outside Paris on their return from Venice. La Maison Louise Carre (main pic) was completed in 1959, for art collectors Olga and Louis who had rejected Le Corbusier deeming his concrete style too austere. Aalto again created a complete package for the couple, with garden design, garage and interiors (now open to the public since since 2007).

Enlivened by family photographs and plentiful archive footage, diagrams and painstaking research, Aalto is a pithy yet concise undertaking that will satisfy professional as well as dilettante appetites. We are left with an impression of the artists as warm, creative and compassionate individuals who would change the face of Finland not just for the few but for the many who continue to celebrate his design legacy all over the world. MT

www.alvaraalto.fi | PREMIERED AT CPH:DOX 2021