Dir: Phil Grabsky | UK Doc, 90′

Edward Hopper (1882-1967) is probably the best known American painter in the world. Mysterious, ephemeral – and despite their bright colours – airless; his depictions of bleak backdrops and isolated people tell a story that allows us to connect on some deep level despite the enigma of the artist himself. Hopper’s work influenced the likes of Rothko, Banksy, Alfred Hitchcock, David Lynch, and even The Simpsons for the unique way it captured 20th century America.

Edward Hopper (1903) Self-portrait

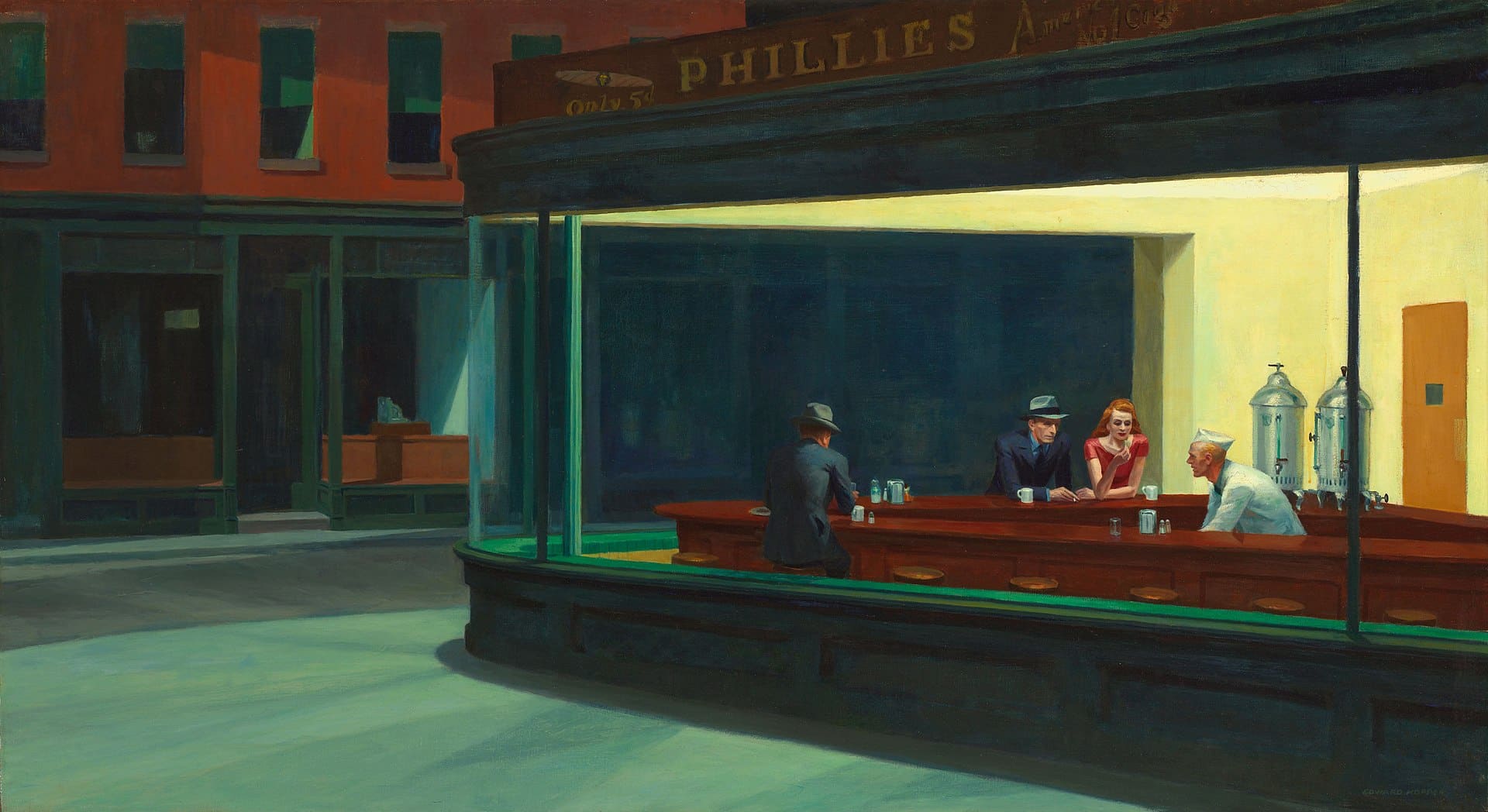

Of his urban landscapes the 1942 painting Nighthawks (main pic) has come to represent loneliness and big city isolation – but that’s not what Hopper had in mind, as we later discover. In this latest art documentary Phil Grabsky uncovers the detached and reclusive artist through his relationships and his life.

Hopper is possibly one of Grabsky’s most immersive biopics to date. The director and photographer combines fascinating archive footage, expert interviews and the artist’s personal diaries to reveal an informative visual reflection of American life in the first half of the 20th century. Refreshingly, Hopper is his own art movement, his work sits entirely on its alone although it is classified as realist, Neo-realist and even impressionist, amongst others. By nature a loner Hopper never tried to connect with any artistic movement, he simply followed his own style, studying art in New York at a time when the US was responding to European avant-garde:. ‘The big painter always has something to say.’

Early Sunday Morning (1930) Edward Hopper

Born into a well-to-do cultured family open to new ideas, the young Hopper was encouraged to be creative, and given the materials to do so, growing up in the riverside town of Nyack (NY). Described as bookish he underwent a growth spurt which made him the subject of bullying when he grew to 6 foot 4′ in his early teens.

Hopper dreamed of being a naval architect, and his interest in the built environment, light and shadow, would dominate his work. But out of economic necessity a career as an illustrator proved lucrative at the turn of the 20th century. And after a ten-year fruitless infatuation with a fellow painter he fell for Josephine Nivison (1883-1967) who gave up her own promising art career to be his manager. They would marry in 1924. Through her we gain so much insight into the private man behind the brush. Together they painted their way through a marriage that wasn’t always emotionally fulfilling for Josephine, but gave the buttoned-down Hopper the buffer he needed from the outside world. She often supported him when he only painted two or three canvasses a year, and a painting could take him months to complete even though the subject was quotidian; such was his intellectual process in telling ‘the story’.

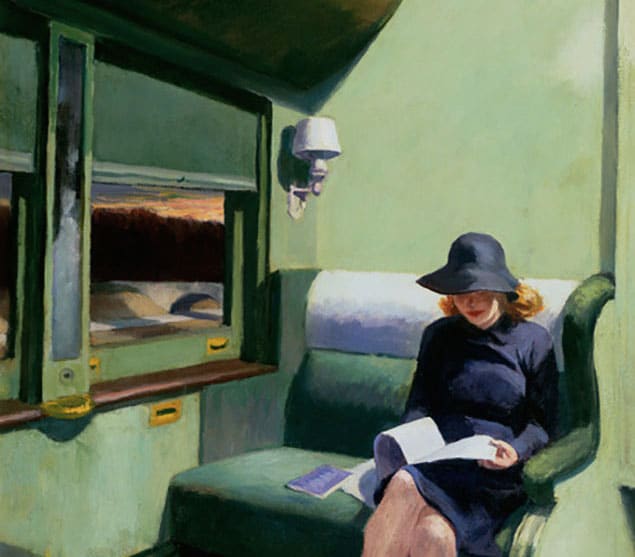

Compartment C, Car 293 (1938) Edward Hopper

A jazzy music score heralds Hopper’s 1913 move to New York’s Washington Square in Greenwich Village where in 1920 he would paint one of his most controversial canvases: Soir Bleu criticised for its misogynist theme. But unlike George Bellows’ exuberant often chaotic NY scenes, Hopper’s paintings here were devoid of noise. Adam Weinberg, director of the Whitney Museum of Modern Art, claims Hopper followed his own unique vision in these depopulated landscapes. Deputy director of Washington’s National Gallery, Franklin Kelly, describes how Hopper depicted NY as an isolating city. Yet it was this sense of isolation that was a natural part of the human condition, according to the Whitney’s Kim Conaty, and Hopper wanted to articulate that.

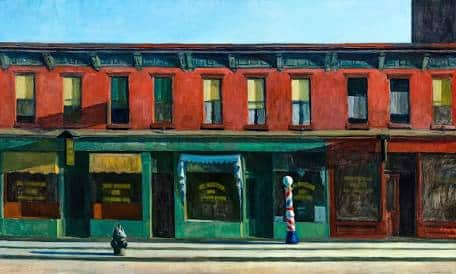

His 1927 Automat painting features a woman on her own in a cafe. But far from lonely, it seems she was actually enjoying a break from the hubbub of the capital’s streets. Yet this stillness seems to be interpreted – often by the critics – as loneliness. Hopper – in an archival interview – clearly states he never thought of it that way. And even though he had no interest in capturing the zeitgeist, his work inadvertently took on a socio-political angle: it charted change. The Great Depression of the 1930s saw women joining the workforce and becoming financially independent. Yet his pictures of the simple low rise buildings and empty streets of New York in the 1930s – such as Early Sunday Morning – convey an enigmatic emptiness that contradicts the hustle and bustle of the time – but therein lies the contradiction in Hopper’s unique view of his world.

Mansard Roof (1923) Edward Hopper

A move to Gloucester Connecticut saw Hopper’s love of buildings and architecture coming to the fore. His most joyous canvas Mansard Roof (1923) was the first painting sold since 1913, when he had hoped the sale of Sailing (1911) would rapidly lead to more. But this ‘mansard’ phase took off with Hopper’s love of light and shadow being the focus of a series of energetic depictions of local buildings providing a pictorial digest of the small seaside town during that time. Lighthouse Hill (1927) would later capture Hitchcock’s imagination for the Neo-Gothic house in Psycho. This interest in film works both way, often inspiring Hopper, as his work influenced other creatives, as in Shirley, Visions of Reality : he also claimed to have felt a deep affinity with Delbert Mann’s noir character Marty (1955). There’s certainly a noirish quality to his Compartment C, Car 293 1938

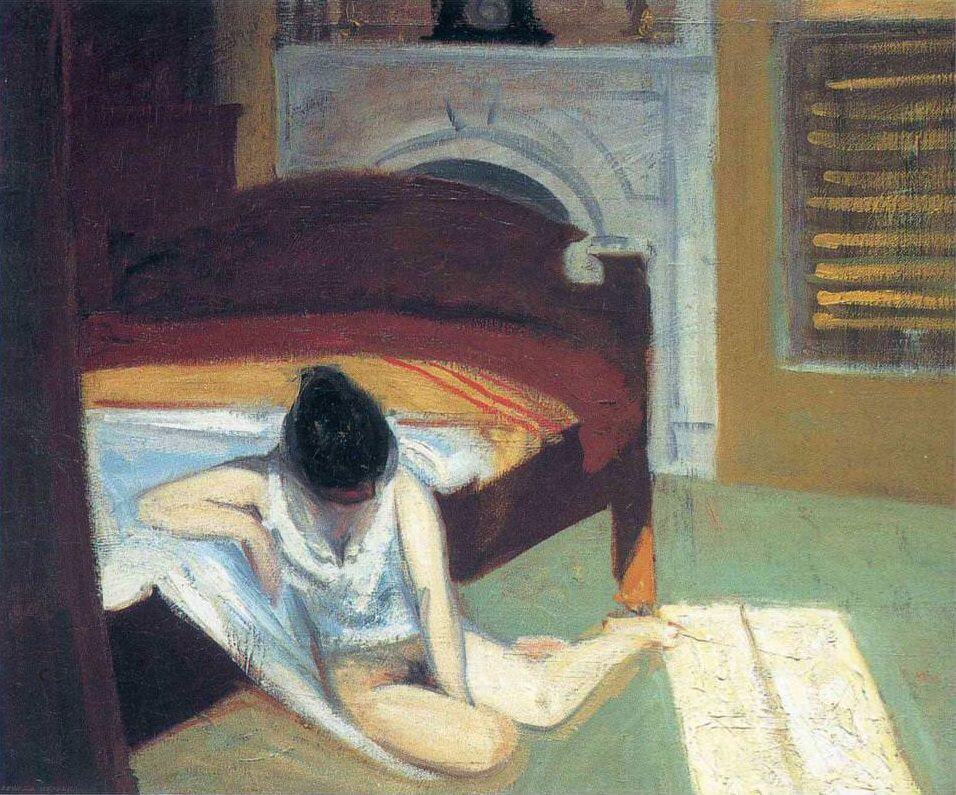

In the early 1930s in seaside village of South Truro, Massechusetts. became the couple’s new home and ushered in a more prolific phase for Hopper. The couple built a house – that still stands today – on isolated sandy road. Together they started to travel backwards and forthwards across the States looking for painting locations where he could explore light and contrast, best seen in Morning Sun (1952) and the much later Sun in an Empty Room (1963). And although these seem to tell troubled stories – Hopper had no interest in revealing himself, or explaining his motives. One of his most devastating pictures is arguably the ironically titled Summer Interior (1909) which appears to show a woman in emotional crisis. But, like the artist himself, her story remains a closed book. MT

Released to coincide with the major Hopper exhibition (Edward Hopper’s New York) at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (Oct 22 – Mar 23).