For the upcoming CITY VISIONS STRAND at the Barbican – Andre Simonoveisz looks at how the social impact of the metropolis is reflected in the cult classics from the roaring twenties to the year 2000.

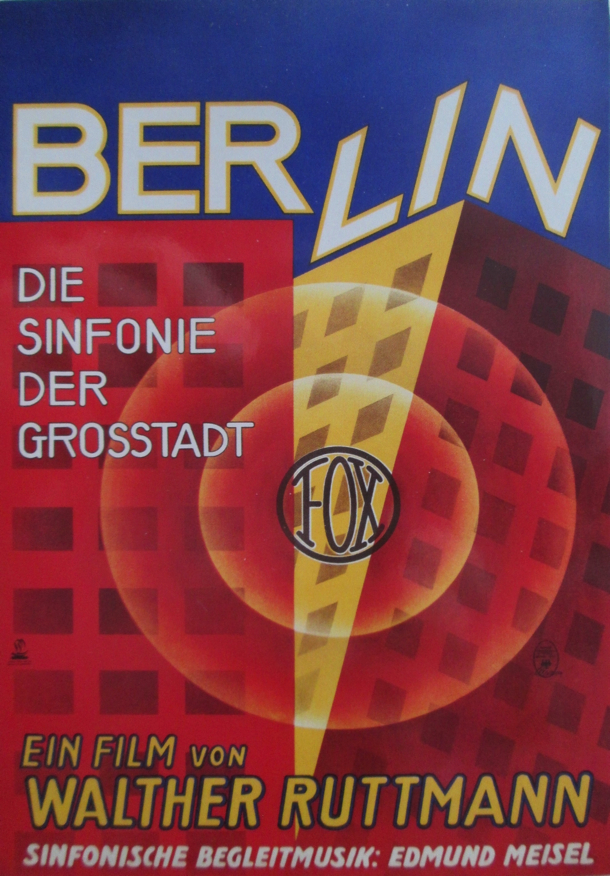

In the beginning there was the city as a growing, permanently moving, uncontrollable juggernaut: Walter Ruttmann’s BERLIN – SINFONIE EINER GROSSSADT (1927) looks at Berlin for twenty-four hours and finds nothing but badly regulated chaos: everything is in motion, but somehow the humans are not the masters of the action but victims of the industrialisation, which enslaves them. After we see workers in the morning, on their way to the factories – shown like demons with their smoking chimneys – Ruttmann cuts abruptly to a herd of cows. But the film lacks any social commentary: rich people in posh restaurants and hungry children in the poorer districts, signify nothing, and are shown in the same superficial way as the delicate legs of a little girl, and the muscular legs of a cyclist. In the end the film is a victim if its own dogma of showing speed at any cost: the viewer is forced to watch, and has no time for any reflections of his own.

Paris, the city were the seventh Art was born, is naturally the setting for the most emotionally charged movies. Whilst many American productions are set in the city of light, we will concentrate on three Parisian filmmakers, and their view of the city they love –or hate. Eric Rohmer, who lived for decades above the offices of his production company “Films du Losange” (which he founded 50 years ago with Barbet Schroeder) in the fashionable 16th arrondissement, set many of his films in Paris, a very gentle Paris as shown in his debut film Signe du Lion (1962). He continued his view through to his Six Moral Tales, and the last of this series L’amour l’apres-midi: a celebration not only of Paris, but of large cities that allow covert liaisons to be conducted in clandestine corners. When Frederic (Bernhard Verley), a lawyer, meets his girl friend Cloe (Zouzou), his wife Helene (Francoise Verley) is meanwhile expecting their second child in a western suburb of the metropolis. Frederic sings Paris’s praises: “I m part of the great throng of people, leaving the Saint-Lazare Station, getting lost in the many little side streets nearby. I love the metropolis. The provinces and suburbs depress me. And in spite of the chaos and the noise I love being part of the masses. I love these masses like I love the sea, not to go under, loosing myself, but to be lone rider on the waves, seemingly following the rhythm of masses, but only to the point that I can follow my own way if the force of the waves dwindle. Like he sea, the masses thrill me and help me to dream. I have nearly all my ideas of the streets of the city, even the ones connected with my work.”

Paris, the city were the seventh Art was born, is naturally the setting for the most emotionally charged movies. Whilst many American productions are set in the city of light, we will concentrate on three Parisian filmmakers, and their view of the city they love –or hate. Eric Rohmer, who lived for decades above the offices of his production company “Films du Losange” (which he founded 50 years ago with Barbet Schroeder) in the fashionable 16th arrondissement, set many of his films in Paris, a very gentle Paris as shown in his debut film Signe du Lion (1962). He continued his view through to his Six Moral Tales, and the last of this series L’amour l’apres-midi: a celebration not only of Paris, but of large cities that allow covert liaisons to be conducted in clandestine corners. When Frederic (Bernhard Verley), a lawyer, meets his girl friend Cloe (Zouzou), his wife Helene (Francoise Verley) is meanwhile expecting their second child in a western suburb of the metropolis. Frederic sings Paris’s praises: “I m part of the great throng of people, leaving the Saint-Lazare Station, getting lost in the many little side streets nearby. I love the metropolis. The provinces and suburbs depress me. And in spite of the chaos and the noise I love being part of the masses. I love these masses like I love the sea, not to go under, loosing myself, but to be lone rider on the waves, seemingly following the rhythm of masses, but only to the point that I can follow my own way if the force of the waves dwindle. Like he sea, the masses thrill me and help me to dream. I have nearly all my ideas of the streets of the city, even the ones connected with my work.”

From his office in the Rue de la Pepiniere (8th arr.), near the Boulevard Haussmann, he often goes shopping, flirting with the beautiful shop assistants; endlessly discussing the colours of a shirt – and making love to Cloe, whilst his wife gives birth to their son. Frederic lives a gentle life and work seems to be only a vehicle for meeting people and having coffee with them in a café round the corner. Rohmer’s Paris does not exist any more, we suspect, that it was mainly part of Rohmer’s imagination – but it was wonderful, nevertheless.

Now we go five years back in time to Jean-Luc Godard’s Two or Three Things I Know About Her (2 or 3 Choses Que Je Sais D’Elle). His anti-consumerist portrait of Paris makes one wonder: did Rohmer and Godard really go to see the same films, never mind writing together for “Cahiers du Cinema”? TWO OR THREE is the antidote to Rohmer’s romantic diary of a man with too much time on his hands – and on top, Godard produced it five years EARLIER. The mind boggles. Paris, by the way, doesn’t get very good grades neither. But one has to know that the “elle” of the title is Paris, undergoing a change for the worse. Rising prices and crass materialism mean that many housewives turn to part-time prostitution, whilst their husbands work in their offices. Needless to say; the husbands hate their jobs and their wives hate being prostitutes and it is all the fault of the giant advertisement boards we can see at length. The narrative follows the housewife Juliette (Marina Vlady), whose child is at nursery, whilst Juliette turns her flat into a part-time brothel. Then she shops for clothing, is accosted by a pimp, who offers her protection for ten percent of her earnings, and in the evening we see her playing happy family. Next we encounter her in a room with another woman, wandering around naked with air flight bags over their heads, to fulfill the sick phantasy of an American called John Bogus. There are off- narration containing agitation and poetry, whilst high-rise buildings rise into the sky, and people are hurrying through the streets. And DOP Raoul Cotard gives the film a Kodachrome-like image, further depicting the alienation of the Parisians, running aimlessly around in the raising tide of consumerism.

Twenty-eight years later, the children of the adult Godard protagonists were most likely languishing with their parents in the cynically called HLM (Habitation à Loyer Modéré) blocks in the newly formed ‘banlieu’ of Paris, were Mathieu Kassovitz’ LA HAINE is set. These bleak high-rise blocks are even worse than the worst of the UK’s so called ‘estates’. Criminality is the norm, particularly among the teenage boys. The film tells the story of three of them: Vinz, a Jew, Hubert, a black boxer and Said, an Arab. They hang out together, terrible bored. They are not ring leaders, but move along the peripherie of the occasional small riots, staying mostly at the Youth centre, waiting for something to happen: their way of life. After an Arab youth is shot, something is going to happen: a major riot. After the school of Vinz’ sister has been burned down, his grandmother warns him “to stay out of it.” On a short trip to Paris, the trio run into trouble with the police. Hubert, being the least violent of the them, draws the attention of the police because of his skin colour. In Mathieu Kossovitz’s 1995 version, Paris has become the citadel of consumerism, Godard warned about. The only difference is that the prostitutes are now real professionals, because the housewives who stay at home can afford to have a good life on one salary – the rest of the undesirables has been “deported” to the banlieu. (London lagging some twenty years behind these developments). The young guys feel rightly that they are now in a different country: banks are the new cathedrals of the city. Shopping malls, full of goods, whose functions they can only guess. The huge advertisement boards have vanished, no need for incitements to buy are needed: shopping is the only game in town. Away from their concrete jungles, the guys react with bewilderment, then, when the police turn on them with hatred. The ending might be predictable, but the film is not: it is about a generation alienated from the society, but it is society itself who has made this choice.

David Lynch had shown in TWIN PEAKS how nightmarish the suburbs can be – but Los Angeles in MULHOLLAND DRIVE (2001) is a ‘city of angels of death’, in a cinematographic, absurd way, of course. To ponder the plot would be to miss the point of the film, it is the ultimate “McGuffin” movie, where all clues end in a cul-de-sac. Still, some sort of narrative develops: Betty (Naomi Watts), is a Hitchcock blond, who is staying as a guest in her aunt Ruth’s apartment in, whilst auditioning for a film role. Rita (Laura Elena Harring) is a brunette, type Rosalind Russell, who is about to be murdered in her limousine, but crawls out the wreck at Mulholland Drive and lands up with Betty. The girls now audition together, meet sinister detectives, a rotten corpse and have lots of lesbian sex. All this explains nothing, but that’s not the point. But LA is the real star of this movie, together with the music, and the permanent quotes of Hollywood’s history. LA has become the studio backdrop for all living in this city, were all genres, but particularly thrillers, are permanently played out – for the living, who are cops, detectives –are so simply victims. The lack of narrative in MULHOLLAND DRIVE coincides with the lack of any rationale in this city – when the whole cplace has become a mega studio, so many stories will collide, and nobody will ask for any logic. Lynch’s film is therefore full of dreams, and they are, more often than not, much more realistic than what’s going on with Betty and Rita. And since every landmark in LA has dozens of movie connections, and many more are in the making, the border lines between life, dream and cinema have vanished. You can have a nightmare like Betty and Rita, but you will wake up, telling your friends, that you have had this awful dream/saw this nightmarish film, and life will go on. Most of the time. AS

CITY VISIONS RUNS FROM 25 SEPTEMBER AT THE BARBICAN LONDON EC2