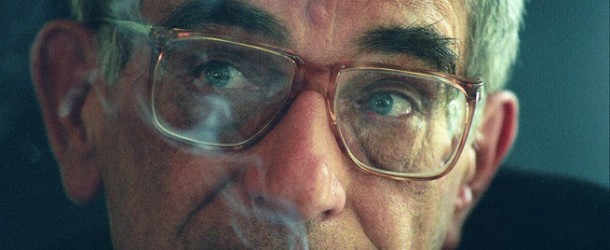

Andre Simonoveiscz met Krzysztof Kieslowski back in 1994 and spoke to him about his ideas surrounding the trilogy.

Very few directors are anything like the main characters in their films: more than often they are just the opposite in style and appearance. But Krzysztof Kieslowski, whom I met at the 1994 Cannes Film Festival, where the last part of his trilogy THREE COLOURS RED (1994) was in competition, was exactly like his films, at least his last four, including THE DOUBLE LIFE OF VERONIQUE (1991). He was sophisticated, subtle, moralistic without being judgemental, detail obsessed, reserved to the point of shyness and a little evasive when it came to pragmatic questions about everyday life or anything that could be construed as political or ideological. It was very difficult to imagine this being the same man who worked for a long time as a documentary filmmaker in Poland, where he was greatly influenced by Wajda’s realistic style. After studying at the famous Lodz film school (where he was finally accepted after two rejections) he embarked on a series of documentaries but had to be pushed into making feature films.

In his DEKALOG (1989/90) films, the last one of which was shot in Poland, Krzysztof Kieslowski had already started to take the position of the observer, letting the narrative develop without any psychological motivations – as just the fly on the wall. “I am only interested in humans, but not in motives, it is not our good intentions which are important, but the most stupid accidents that are interesting.”

In THREE COLOURS, the characters are literally overwhelmed by the aesthetics. The trilogy explores the virtues symbolised by the French Flag: Liberty, Equality and Fraternity – the trio of stories is also about love and loss and defined the art-house movement of the nineties with their cinematic quality and emblematic humanity that ranged from tragedy through to comedy. The trilogy follows the experiences of a group of loosely interconnected characters the trilogy garnered an impressive array of awards at the major European film festival winning the GOLDEN and SILVER BEARS at Berlin and the GOLDEN LION at Venice culminating in three Academy Award nominations.

Juliet Binoche plays Julie in THREE COLOURS: BLUE losing her famous composer husband and little daughter in a car accident at the beginning of the film (the ball popping out of the car wreck is three coloured: red, blue and white). Later on in the Palais de Justice in Paris, she accidentally drops into a divorce hearing of a Polish/French couple: Karol and Dominique, who we will meet in THREE COLOURS WHITE (1994).

Kieslowski’s obsession with the smallest details is shown in the scene when Olivier (her husband’s assistant, who is in love with her) finally tracks down Julie who ignores him as she toys with her coffee, allowing the sugar cube to soak up the liquid. Deciding that the sugar cube would take precisely five seconds to soak up the liquid, Kieslowski had his assistant director test multiple brands to find one that took exactly the right time.

Julie then abandons all her worldly possessions eventually giving them to her husband’s mistress and unborn child, in an act of profound selflessness – because of the housing crisis at the time. I asked Kieslowski if this generosity seemed bizarre in the scheme of things, he was adamant. “Look, today we are all more or less on the same level, if we need a dentist, we can usually get one, everybody has enough”.

In THREE COLOURS: WHITE. Karol and Dominique are a married couple in Paris, but Karol has become impotent – the pressure of being with his beautiful and rich wife being too much for him. He re-emigrates to Poland, where he makes a fortune on the black market, invites Dominque to see him, fakes his own death for which she is, as intended, convicted, but falls in love again when visiting her in prison. WHITE, so Kieslowski says, “shows, that there is no possibility of equality ever. But there is a possibility of ‘brotherhood’, which is shown in the final segment of the trilogy THREE COLOURS: RED.

Fashion model Valentine (Irene Jacob) rescues a dog belonging to a judge (Jean Louis Trintignant), who strangely shows no emotion on being reunited with his pet. He is a man with few close ties although he eavesdrops on neighbours’ and strangers’ conversations. But Valentine somehow manages to get through the armour the judge has built around himself. And the equality here? Well, all the main participants of the trilogy get together, unknown to each other, on an English ferry, which sinks. Only seven are rescued. Needless to say Kieslowski warned not to give away the ending in an atypically pragmatic way: “Don’t tell how the films end. Then nobody will buy a ticket!”

When asked if the three colours red, white and blue refer to the Freedom, Equality and brotherhood, the ideals of the French revolution, Kieslowski is rather dismissive: “The money for these films came from France, so we thought about the colours of the Tricolore, and the ides of the revolution, for which many people fought and died. But we were very naïve because we imagined the French would still abide by these ideals, like Poles with the Eagle and the blood. But this was not the case. Had money come from Germany, we would have constructed a black-red-gold metaphor.”

Kieslowski is well-known for his meticulous, painstaking hours spend in the editing suite. Asked why, he answered “This is my favourite phase of the filming process. Only whilst editing do I have everything under total control.” Asked if he had difficulty eliminating footage to produce the end film he says “I am trying to take more and more away, so that in the end only the really core of the action is left. But one always thinks that the last version is the best, but if you try again maybe?…” He tried, once, to have 17 different versions of THE DOUBLE LIFE OF VERONIQUE distributed in Paris cinemas – the producer did not take gladly to this idea. Surprising really.

THE THREE COLOURS TRILOGY IS NOW BACK IN CURZON CINEMAS and Home Cinema 2033

|

|