BERNHARD HERRMANN: THE HITCHCOCK YEARS

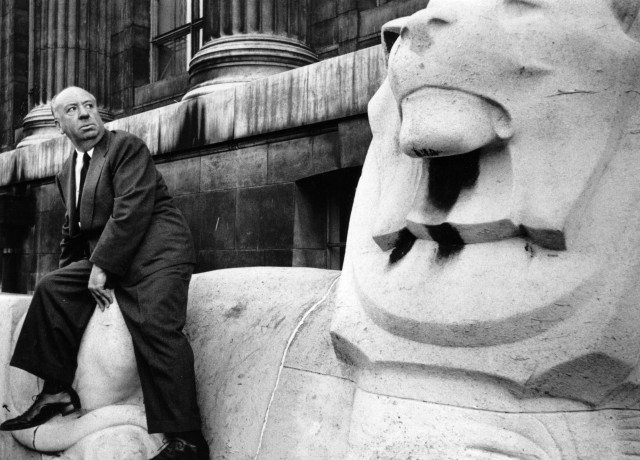

The Hollywood composer Bernhard Herrmann (1911-1975) is mainly remembered for his collaboration with Alfred Hitchcock between 1955 and 1965. Herrmann also scored the music for 17 episodes of the TV series “The Alfred Hitchcock Hour” during this decade. Like his contemporary Erich Wolfgang Korngold, Hermann was educated in Classical music; and shared both strands for the rest of his life. Herrmann’s film music for Hitchcock is particularly remembered for its dissonant and oppressive tonal structure, as well as non-dietic score, even though the composer used these themes as early as 1947 for The Ghost and Mrs. Muir, directed by Joseph L. Mankiewicz.

Herrmann, the first (and possible only) music ‘auteur’ in the history of cinema, insisted on artistic freedom when composing, and he also usually conducted the orchestra. Hitchcock, whose Ego was easily matched by Herrmann’s, had enormous respect for the composer: during the shooting of Vertigo he marked in his sound track notes “We should let all traffic noises fade, because Mr. Herrmann may have something to say here”, and “All of this will naturally depend on what music Mr. Herrmann puts over this sequence.

But they began collaborating with the rather uninspiring The Trouble with Harry (1955). The main theme of this and other Hitchcock/Herrmann movies was “a series of plucked notes from the musicians own double bass, giving a weird feeling that ghastly intangibles are stalking the ‘hero’ into a world of eerie bewilderment and horror”. The most famous scores for Vertigo (1958), North by Northwest (1959) and Psycho (1960) interacted with the main title sequences, designed by Saul Bass.

In the case of Psycho, the music came first and the graphic animation was responding to it. Whilst these “overtures” were quiet common, Herrmann’s music was extremely idiosyncratic. He was a great believer in this form of introductory music, and was aghast, when Brian de Palma later suggested, that Sisters should start without any score. Herrmann’s later Hitchcock scores were “relying on ostinato figurations, refusing themselves to be transformed into conventional melodies. They formed a kaleidoscope of musical textures that tread a precarious middle-ground between stability and instability (Vertigo) or reduced to an obsessive degree of insistent economy (Psycho).” In the case of the latter, Hitchcock had not planned any music for the famous shower scene. The harshly recorded “screeching and slithering string glissandi”, which accompanied Janet Leigh into her watery death, made many critics at the time think, that they were electronically generated.

Other critics were induced to describe the scene much more brutally than it actually was, largely due to the music. But the shower scene took the attention away from other Herrmann ideas, like in the scene where Leigh takes off with the money, and “the unobtrusive synchronisation of the doom-laden, pulsating music to the action of windscreen wipers”, as Leigh is driving through the night. But without the music, Leigh might as well have been on her way to do the weekend shopping and feeling stressed and anxious about it. (Actually, Hitchcock had not envisaged any music for this drive scene). In Vertigo, by far the least frenetic of their common films, the long sequences without much talking, invited a doom laden musical score. And in his soundtrack notes, the Hitch wrote: “When Madeleine goes up to Scottie, and we see her face in a close-up, we should have no restaurant background sounds, so as to create a silence which shows that something in Scottie is moved. When Madeleine’s husband is coming into the frame, the background sounds should return, until she leaves the frame. I have no idea which music Mr. Herrmann would choose, but should he decide not to have any music at all, in case it should sound like restaurant music, then it would be preferable to have no music at all so as to mark the moment when Scottie discovers Madeleine, with silence”.

But Herrmann decided, as always, that music was vital. Ironic then that the only time Hitchcock insisted on a scene without music – the murder scene in Torn Curtain when the GDR agent Gromek meets a brutal death – it was because Hitchcock wanted to demonstrate how difficult it is to kill someone. Bernhard Herrmann lost the argument here. But Torn Curtain (1965) was (not even) their swansong. After Marnie (1964) bombed at the box office, the studio asked Hitchcock for a more youth-orientated ‘pop’ score, for Torn Curtain. (1966/8) Herrmann refused and Hitchcock ended their relationship – their final meeting would be at the Universal lot.

But Herrmann would go on to have the last laugh: in 1991, when Elmar Bernstein re-arranged Herrmann’s music for Lee Thompson’s Cape Fear (1962) for Martin Scorsese’s remake of 1991, he used the soundtrack for Gromek’s murder scene. As the Hitchcock epigone Claude Chabrol put it: “Once Hitchcock got rid of Herrmann the music only succeeded when it was imitating Herrmann”. Hitchcock refused Henry Mancini’s musical score for Frenzy (1972) simply because it sounded too much like Herrmann. He had it replaced by a Ron Goodwin score. Hitchcock had the last word. AS