Martin Scorsese: An Alternative Top Five

To celebrate the release of Martin Scorsese’s new film, SILENCE and the BFI’s current Retrospective, ALex Barrett explores some of the director’s lesser-known past gems.

It seems safe to say, without fear of hyperbole or exaggeration, that Martin Scorsese is widely considered to be one of cinema’s greatest directors. And yet, at least in the wider public consciousness, it seems that myths and misunderstandings endure: he still remains known primarily as the maker of sweary, violent gangster films. If The Wolf of Wall Street swaps the violence for comedy, it certainly retains the swearing. The film tells the tale of stockbroker Jordan Belfort, from his days as a wide-eyed novice to drug-addled leader of a ‘wolf-pack’ of traders who work enough deals on the wrong side of the law to catch the attention of the FBI. In this, the film contains a rise and fall arc that closely mirrors those found in GoodFellas and Casino, meaning that Wolf slides unproblematically into the popular conception of Scorsese’s oeuvre – for what are stockbrokers, if not the crooks and money-launderers of today?

If the description outlined above does, unarguably, fit the filmmaker, it’s also true that he is so much more: his oeuvre, one can’t help but feel, is often not given the credit it deserves for the diversity it contains. Even with Wolf, some are calling comedy a new area for Scorsese, thus overlooking his previous foray into the genre with the low-budget cult curio After Hours (1985). Indeed, the lack of wider recognition for the ‘smaller’ pictures means that it now seems possible to posit an ‘alternative’ top five films – those that are loved by some, overlooked by many, and whose greatness, at times, even eclipses that found in the more readily-recognisable work.

There are, undoubtedly, recurring themes that run throughout Scorsese’s work, and these themes offer a bridge from his gangster pictures to the work discussed below. Two themes seem especially prevalent: religion and relationships – relationships not only between men and women, but also between friends and family, man and society, and man and money. The latter of these, of course, is the primary concern of Wolf, though it’s also true that, as in GoodFellas et al., there’s a strong exploration into marital relations. More specifically, these films show the strain of relating to someone who wishes to succeed professionally above all else – and this leads us to a third key theme: reflexivity. Scorsese’s films are nothing if not steeped in cinema, and it’s possible to read almost all of his work as being, in some way, about his own obsessive need to create. Looked at in this way, the excess of Wolf becomes readable as autobiography – Scorsese’s past drug use, and his resulting collapse, has been well documented. Is Jordan Belfort’s addiction to money and the market really so different from Scorsese’s addiction to filmmaking?

There are, undoubtedly, recurring themes that run throughout Scorsese’s work, and these themes offer a bridge from his gangster pictures to the work discussed below. Two themes seem especially prevalent: religion and relationships – relationships not only between men and women, but also between friends and family, man and society, and man and money. The latter of these, of course, is the primary concern of Wolf, though it’s also true that, as in GoodFellas et al., there’s a strong exploration into marital relations. More specifically, these films show the strain of relating to someone who wishes to succeed professionally above all else – and this leads us to a third key theme: reflexivity. Scorsese’s films are nothing if not steeped in cinema, and it’s possible to read almost all of his work as being, in some way, about his own obsessive need to create. Looked at in this way, the excess of Wolf becomes readable as autobiography – Scorsese’s past drug use, and his resulting collapse, has been well documented. Is Jordan Belfort’s addiction to money and the market really so different from Scorsese’s addiction to filmmaking?

In Life Lessons (1989), Scorsese has Nick Nolte’s character verbally express this idea: ‘you make art because you have to – because you have no choice’. But the line is also (surely) a reference to a key exchange between Lermontov (Anton Walbrook) and Victoria (Moira Shearer) in Michael Powell’s The Red Shoes (1948):

Lermontov: Why do you want to dance?

Victoria: Why do you want to live?

Lermontov: Well I don’t know exactly why, but I must.

Victoria: That’s my answer too.

As we shall see, this obsession, and its expression in The Red Shoes, would go on to have a profound impact upon Scorsese’s own work.

5. The Color of Money (1986)

If Scorsese’s career can be understood as operating within a ‘one for me, one for them’ framework, The Color of Money belongs firmly in the ‘one for them’ camp. And yet, despite this, it’s important to remember that Scorsese himself had a strong hand in the construction of the screenplay. His first major Hollywood film, Color came at an uncertain time in the director’s career: following the success of Raging Bull (1980), the 80s had consisted of a high-profile flop (The King of Comedy, 1983) and a failed attempt to make a long-cherished personal project (The Last Temptation of Christ, eventually realised in 1988) – both of which had taken a toll on Scorsese. Dealing as it does with an ageing pool player struggling to stay in the game, it’s hard not to read Color as a reflection upon the mental state the director was in. Scorsese could see that the Hollywood of the 1980s was becoming an increasingly commercial landscape, and that personal auteur cinema was on its way to becoming a thing of the past – something else reflected in the very fabric of Color, through the casting of its two leads: Paul Newman and Tom Cruise. In a sense, the film is about the resistance of one generation in giving way to the next: and this is as true for Scorsese as it is for Newman’s character. Together with After Hours, Color revived Scorsese from the depths of despair and its success allowed him – finally – to get The Last Temptation of Christ made. For that alone, the film would be worthwhile, but there’s much else to enjoy in this sadly neglected masterwork. If only all directors could make films this rich, and this personal, when working for ‘them’.

If Scorsese’s career can be understood as operating within a ‘one for me, one for them’ framework, The Color of Money belongs firmly in the ‘one for them’ camp. And yet, despite this, it’s important to remember that Scorsese himself had a strong hand in the construction of the screenplay. His first major Hollywood film, Color came at an uncertain time in the director’s career: following the success of Raging Bull (1980), the 80s had consisted of a high-profile flop (The King of Comedy, 1983) and a failed attempt to make a long-cherished personal project (The Last Temptation of Christ, eventually realised in 1988) – both of which had taken a toll on Scorsese. Dealing as it does with an ageing pool player struggling to stay in the game, it’s hard not to read Color as a reflection upon the mental state the director was in. Scorsese could see that the Hollywood of the 1980s was becoming an increasingly commercial landscape, and that personal auteur cinema was on its way to becoming a thing of the past – something else reflected in the very fabric of Color, through the casting of its two leads: Paul Newman and Tom Cruise. In a sense, the film is about the resistance of one generation in giving way to the next: and this is as true for Scorsese as it is for Newman’s character. Together with After Hours, Color revived Scorsese from the depths of despair and its success allowed him – finally – to get The Last Temptation of Christ made. For that alone, the film would be worthwhile, but there’s much else to enjoy in this sadly neglected masterwork. If only all directors could make films this rich, and this personal, when working for ‘them’.

If, in Color, Scorsese hints that ‘pride causes suffering’, in Kundun, the idea is expressed verbally. A film about the early life of the 14th Dalai Lama, Kundun is, along with The Last Temptation of Christ, Scorsese’s most explicitly spiritual work – and like Scorsese’s Christ, his Dalai Lama must renounce the comforts of secular society in favour of religious calling. In Kundun, this conflict erupts onto the level of politics: how can religion combat communism, and how can violence be reconciled with religious belief? If Scorsese’s gangster pictures can be understood as being, in part, examinations into the ‘problem’ of violence, then so too can Kundun: it is a study of the flipside – the act of nonviolence. It seems almost as if Scorsese is exploring Buddhism, searching for answers to questions raised in his earlier work. Perhaps, Kundun seems to say, if Scorsese’s protagonists are their own worst enemies, Buddhism can offer them salvation.

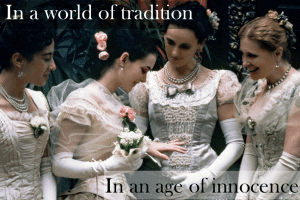

3. The Age of Innocence (1993)

3. The Age of Innocence (1993)

Where Kundun deals with the repression of violence, The Age of Innocence deals with the repression of feeling. Like both the Dalai Lama and Christ, Age‘s protagonist Newland Archer (Daniel Day-Lewis) must sacrifice a life of pleasure for something higher – though this time, the ‘something higher’ is societal, not spiritual: Archer is engaged to May Welland (Winona Ryder), and the moral standards of 1870s New York force him to honour his commitment to her, despite his love for the smouldering Countess Olenska (Michelle Pfeiffer). Where May represents ‘all that is best’ in Archer’s world, Olenska is all that is fun – at one point, she strides into an evening’s entertainment in a flaming red dress, all the better to set Archer’s world alight amongst the black and white formal wear of the world around him. Emotionally complex and deeply moving, Age allowed Scorsese to expand his stylistic palette and expose a new facet within his on-going explorations into New York life and codified societies (the laws of 1870s society are not so different, it would seem, from those of the 1970s mafia). With its use of voiceover narration and its detailed recreation of the minutiae of a by-gone age, The Age of Innocence surely ranks alongside Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon as one of the greatest literary adaptations ever filmed.

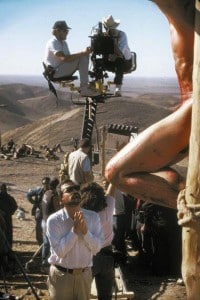

2. The Last Temptation of Christ (1988)

2. The Last Temptation of Christ (1988)

A long-cherished personal project for Scorsese, The Last Temptation of Christ is perhaps the purest expression of an idea that runs throughout his entire oeuvre: the battle between the ‘spirit’ and the ‘flesh’. Indeed, those very words appear on screen at the beginning of Christ, embedded within a scrolling quote that posits the soul as the ‘arena’ in which ‘these two armies have clashed’ in ‘merciless battle’. The quote is from Nikos Kazantzakis’ source novel The Last Temptation, but one feels as though it could have been written by Scorsese himself – indeed, alongside the famous opening words of 1973’s Mean Streets (‘You don’t make up for your sins in church – you do it in the streets‘) it’s possible it provides the key to understanding almost all of Scorsese’s tortured antiheroes. A blistering work of religious and spiritual angst, The Last Temptation courted huge controversy upon release, seemingly for daring to humanise Christ – but it’s this very humanisation that makes the film such a powerful retelling of Christ’s story. If Christ is not human, if he does not share our longings and desires, then his death is no great sacrifice. But even more than this, by exploring Christ’s deep sense of existential conflict, Scorsese allows us to identify with his plight, and to feel his pain – just like we do all of Scorsese’s protagonists.

1. New York, New York (1977)

The gripping story of a saxophonist torn between his love for music and his love for his wife, New York, New York relocates Christ’s dichotomy of spirit versus flesh into a secular setting – this time, our protagonist must choose between family life and his obsessional desire to succeed in his musical career. Seen in this way – as a film about someone whose personal life is torn apart by their love of a performing art – NYNY becomes understandable as The Red Shoes replayed. The Red Shoes, let’s not forget, is the story of a woman whose obsession for ballet leads her away from her husband and towards death – and this self-destructive streak is there tenfold in NYNY’s saxophonist Jimmy Doyle.

In portraying Doyle, Robert De Niro gives arguably a career-best performance: one minute he’s exchanging the zingiest one-liners in Scorsese’s entire oeuvre, the next he’s a terrifying ball of rage. But despite all this, the film was a huge flop, and Scorsese collapsed into depression and drug addiction. It was De Niro that saved him, by persuading him to make Raging Bull – a film readable as the story of a man whose personal life falls apart due to his obsessional desire to succeed in a performance sport. Sound familiar? There’s certainly an argument to be made that Scorsese subconsciously reworked his flopped musical project within a genre then more in vogue. But perhaps it was simply a return to The Red Shoes, the film that so fascinated Scorsese as a child (lest we forget, it was Michael Powell himself that suggested Scorsese shoot Raging Bull in black and white). Indeed, even now, with Wolf, it seems Scorsese has not left the shadows of Lermontov and Victoria behind – for Belfort, too, is a performer, and he too is his own worst enemy. Like Jimmy Doyle and Jake LaMotta before him, it is ultimately his own obsessive addiction that leads him down a spiral of (self) destruction. ALEX BARRETT

SILENCE IS ON GENERAL RELEASE FROM 1 JANUARY 2017 | THE SCORSESE SEASON AT THE BFI CONTINUES THROUGH JANUARY 2017