Dir.: Catherine Breillat | Cast: Caroline Ducey, Sagamore Stevenin, Francois Berleand, Rocco Siffredi | France 1999, 84/99 min.

Dir.: Catherine Breillat | Cast: Caroline Ducey, Sagamore Stevenin, Francois Berleand, Rocco Siffredi | France 1999, 84/99 min.

Catherine Breillat, novelist and filmmaker, has been a victim of censorship (and misinterpretation) from the beginning of her career as a cinematographer: her debut film Une Vraie Jeune Fille (1975), based on her own novel Le “Sopirail” was banned after its premiere until 1999. Influenced very much by George Bataille (whose 1928 novel “Histoire de l’oeil” was wrongly indicted for pornography), Breillat, too, had to fight off the same accusations.

Her heroines do not fit into the mainstream categories of either victim or aggressor: they like their sex in whatever form, but at the same time they want to determine their lives; fighting their male partners successfully for domination in their relationships. And they are no goody-two-shoes: Barbara in Sale Comme Un Ange (1991), is married to the young detective Didier Theron, and willingly seduced by his much older superior George Deblache, who might be a drunkard, but satisfies her carnal needs much better than her bland husband. Deblache gets Theron killed on a job, and slaps Barbara at the end of the film: he is only now aware of her manipulating, whilst she smiles like the cat that got the cream.

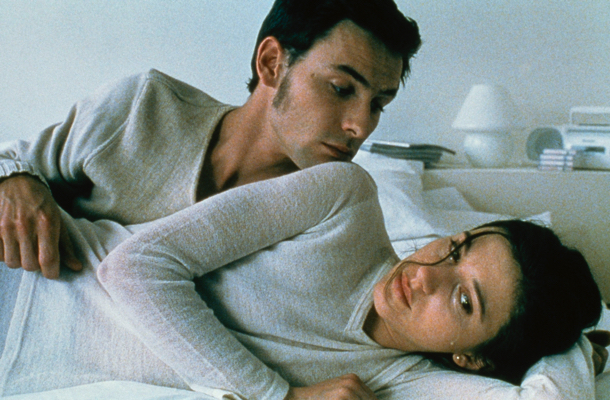

Marie (Ducey) in ROMANCE (1999) chooses a not so different way to punish her narcissistic boyfriend Paul (Stevenin) for his refusal to sleep with her, simply because he wants to control her. First Marie, a primary teacher, has a casual affair with Paolo (Siffredi, a well known porn star), then she plays S&S games with her headmaster Robert (Berleand). Somehow, she gets Paul to sleep with her after all, and the resulting pregnancy makes him even more removed from her, neglecting her in favour of friends and relatives. But he ends up paying the price: after the birth of Paul junior, only one male with this name ends up being part of Marie’s life.

Breillat’s films show an understanding of women’s sex life from their own perspective – just the opposite of the male view that is usually trotted out. Whilst male sexual transgressions (in films and books) are usually tolerated, Breillat’s female counterparts are censured, her films condemned as pornographic. Like Simon de Beauvoir and Bataille; Breillat in her novels and films, often adds an essayistic character, strong symbolism and abstract images, best described by Linda Williams as “elitist, avant-garde, intellectual and philosophical pornography of imagination, [as opposed] to the mundane, crass materialism of a dominant mass culture”. Whilst one can describe male sexuality (including nearly all phantasies) as strictly one to one, meaning that there is no ambivalence left, actions and desire are one, female sexuality thrives on ambiguity and imagination. Whilst sex from a male perspective (and its mostly male descriptions in all forms) is treated as an object. For Breillat and her heroines, sex is the subject of their emancipation. There is no pleasure in Breillat’s sexual images, the best example being Marie’s encounter with a man on the staircase. The man offers her money for performing cunnilingus on her, but she does not take the money. Instead she turns over, having rough sex doggy-style. The scene ends highly ambiguously: Marie cries, but when the man calls her names, she retaliates: “I am not ashamed”. Further more, the whole scene begins as voice-over, Marie informing us that this particularly way of being taken, is her phantasy. In blurring the boarder between phantasy and reality, Breillat leaves the audience to judge what they have seen, and how to categorise it. This is just the opposite of conventional pornography, where a mostly male audience is never left in any doubt what is going on, taking their pleasure from the submission of the female.

In A Ma Soeuri! (2001) Breillat went a step further, trying to redefine rape: Anais (12) and Elena (15) are sisters; the latter attractive and sexual active, the former overweight and insecure. On a parking lot, an attacker kills Elena and her mother, afterwards raping Anais. When questioned by the police, the young girl stoical denies having being raped, in her experience, she has at long last caught up with the experience of her sister: for the first time in their rivalry she has come out on top. Breillat’s interpretation gives room for misunderstanding, as does the use of un-simulated sex in her films – but she is a major figure of modernist filmmaking; her films are dominated by reflectiveness and a desire to reinvent class consciousness; not via an out-dated model but by describing women as a class via their experience of sex: Breillat is an innovative heir to the ideas of de Beauvoir’s “Le Deuxieme Sexe”. AS

NOW OUT ON BLURAY COURTESY OF SECOND SIGHT FILMS and BFI Player