Dir/Wri: Firouzeh Khosrovani | Doc, Iran, Norway, Switzerland 82′

Firouzeh Khosrovani’s prize-winning documentary chronicles her early life against the background of Iran’s revolutionary recent history.

Delicate and deeply moving – sorrowful even – Khosrovani’s fourth feature is a tragic love letter to a childhood and early adulthood blighted by the growing distance between her parents largely due to the revolution and her mother’s religious fundamentalism.

With its resonant cultural and political touchstones, Radiograph is an compelling and elegantly assembled collage of memories and photographs, narrated by actors and describing the simple joy of her parent’s early days together in Geneva: her father Hossein was training to be a doctor in Switzerland, inviting her mother Tayi to join him there in the early 1960s.

Recorded on Super 8 footage, ten years before the filmmaker’s birth, it tells of a couple who fell in love but whose aspirations turned to dust as the silent shadow of revolution gradually spread into every aspect of their life together, eventually threatening the stability of the family. What stands out is deep sadness and regret, rather than anger or bitterness, and we feel for Firouzeh and her broken dreams.

Switzerland is home to many Iranians and Hosseini had chosen to study medicine in the thriving cosmopolitan lakeside city of Geneva. The hard-working radiographer was able to offer a good life to his much younger wife when she arrived from pre-revolutionary Tehran. For a timid young girl Tayi certainly knew her own mind, praying to Mecca while her husband preferred to meet his urbane friends in glamorous bars and listen to music. Eventually Tayi used her new pregnancy and back problems as the kicker to return home, persuading Hossein to move back to Iran where she was delighted to be reunited with her friends and growing family.

In the 1960s Tehran was a sophisticated, thriving metropolis where the middle classes enjoyed summers by the Caspian Sea and winters on the ski slopes. But once the Shah was toppled things changed, and from then on Tayi became increasingly drawn to her religion.

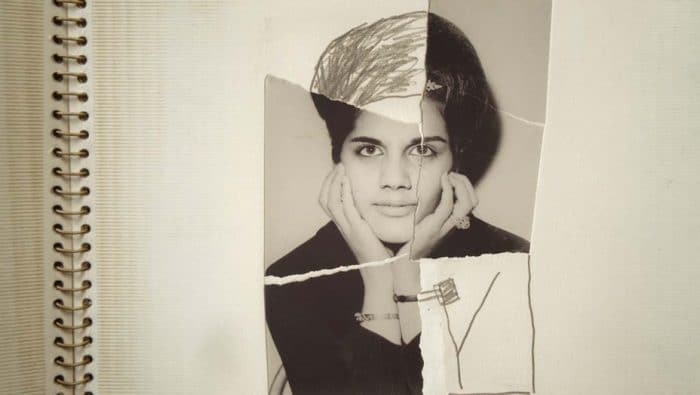

Khosrovani’s enlivens her portrait with family photographs picturing her parents’ early days in Geneva before moving back to Tehran on the birth of their first child named Firouzeh (herself). Back in Iran, Tayi questions Hossein’s lack of prayer routine as she pursues Islam with growing fervency and self-determination, rejecting her husband’s way of life and even tearing up the family photos and snaps, which the director has since pieced together for her film.

Both visually and narrative-wise Khosrovani uses her family home in Tehran as a recurring motif and the feature’s fulcrum. What starts as a comfortable and soigné home soon becomes the sober backdrop to her mother’s strict religious beliefs: her parents’ elegant bedroom adorned with her father’s favourite piece of modern art (a female nude) soon morphs into a spartan single room where reflection and prayer are the order of the day, a long table accommodating her mother’s new friends, the proponents of the oppressive Islamic regime. “The revolution entered our house,” the director recalls, as her heavily veiled mother is pictured requesting the whereabouts of her Quar’an.

Radiograph is a deeply subjective view of a child’s fond memories projected into an adulthood full of anguish and sadness, that still lives on today. No matter how much happiness and contentment we find as adults, our early childhood experiences will always colour our future. Khosrovani maintains a non-judgemental approach to her parents throughout her film. And although she never condemns her mother, maintaining a neutral acceptance of her beliefs, it is clear that her father embodies her hopes and dreams. Bonds of sadness and regret can often be more resilient that those of shared joy. In the end acceptance is one form of contentment. MT

NOW AT THE DOCHOUSE Radiograph of a Family | World premiered at IDFA documentary festival in Amsterdam, where it won the main prize for best feature