Dir.: Gregory Monro; Documentary with Stanley Kubrick, Michel Ciment, Malcolm McDowell; France/USA 2020, 72 min.

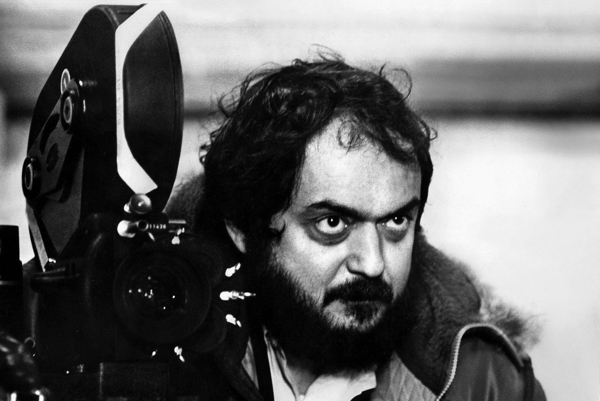

Seasoned documentarian Gregory Monro (Michel Legrand: Let the Music play) unpacks more gems, this time the focus is legendary filmmaker Stanley Kubrick (1928-1999). Kubrick by Kubrick sees Monro teaming up with French film critic Michel Ciment and enriched by interviews with the maestro and stars: Malcolm McDowell, Sterling Hayden, Jack Nicholson, Shelley Duvall amongst others.

In the wake of Kubrick memorabilia docs Stanley Kubrick’s Boxes and Filmworker Gregory, Monro goes for the jugular, with the help of Michel Ciment (who wrote a seminal book about Kubrick in 1982). Probing for the meaning behind the films. What emerges is a dry witted perfectionist; a keen intellect whose craft was everything.

Ciment (“Kubrick tolerated me for while”) started his 20+ year relationship with the interview-shy New Yorker in 1968, after writing a major article about Kubrick, the first one in France, in Positif in 1968. Kubrick had by then moved permanently to live in England: first Elstree/Borehamwood, near to the studios, then in 1978 to Childwickbury in Harpenden, Hertfordshire, where he edited his films, surrounded by his third wife Christiane Harlan (niece of NS-director Veit Harlan), three daughters and countless cats and dogs. He literally run the film world from his house. Legend has it that Kubrick was a control freak, but actors contradict this strongly: he often came unprepared for the day’s shooting, actors writing their own lines. McDowell defends the maestro’s spontaneity, claiming it the key to true creativity. Kubrick has the last word: “It’s where the ball bonces on the set, that’s where opportunities arise”.

Peter Sellers came up with the idea of Dr. Strangelove’s ‘independent arm’ rising for the Nazi salute. And Malcolm McDowell claims the choice of Singing in the Rain, was his in Clockwork Orange. Shelley Duvall, driven to tears by Kubrick on the set for The Shining, is quoted: “After a while, an actor would get dead inside – for maybe five takes. But then, they’d comeback to life, and you’d forget all reality other than what you’re doing.” Which does not mean, that Kubrick the perfectionist didn’t exasperate his collaborators. “I like to get things right, and this can lead to personal conflict, which isn’t popular”. Sterling Hayden complains bitterly about the soul-destroying effect of repetitive takes. But Kubrick got what he wanted on the occasion: “the fear in your eyes, that’s what I’m looking for”. Composer Leonard Roseman (who conducted the Barry Lyndon score) told Kubrick after the 105th take: “We are dealing with an insane person. You have driven everyone crazy.” And even though Kubrick watched 100 hours of documentary footage of the Vietnam war, he still insists, “that one of the things that characterises some of the failures of 20th century art, is an obsession with total originality. Innovation means moving forward, but not abandoning the classical art form you’re working with.”

In the end, Monro has to conclude that Kubrick’s films are, for the most part, about war and violence. The field of corpses in Paths of Glory or Spartacus are just some examples of human slaughter, but war or conflict can also be on a personal domestic level as experienced in The Shining and Lolita. There’s clearly ambiguity about the violence in Clockwork Orange, as McDowell concedes: “You are not supposed to be rooting for them, but…”.

So Munro comes away with more questions than answers to his film’s pivotal question: What are Kubrick’s film about?. From his early days as a photographer and as a novice filmmaker (Killer’s Kiss), he was obsessed with boxing, his love of the sport is documented by shots of an entranced young Kubrick. And chess which, he claims, taught him patience and discipline.

We end, quite aptly, with 8 mm films of Kubrick’s childhood with his younger sister (Al Bowlly singing ‘Midnight, The Stars and You” from The Shining), and his home life in leafy Hertfordshire, a recreation of the Royal Court’s afterlife scenes from 2001 as a doll-house set provides the leitmotif, rounding up a fascinating portrait of a filmmaker who was – to a large extent – all brain, but could never totally conceal the tough New Yorker beneath. AS

The 55th Karlovy Vary IFF will take place in 2021. Meanwhile Karlovy Vary IFF is organising KVIFF at Your Cinema showcase | SCREENING DURING KVIFF | 4 JULY 2020