Dir.: Paul Katis;

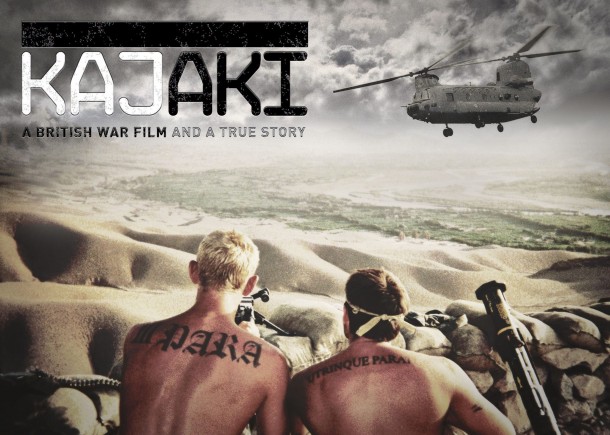

Cast: Mark Stanley, Malachi Kirby, David Elliot, Paul Luebke, Ali Cook; UK 2014, 108 min.

KAJAKI – the true story – is debut helmer Paul Katis’ account of an incident near the Kajaki dam in the southern Afghan province of Helmand in 2006, involving a group of British soldiers, when a routine mission turned into a nightmare.

One has to stress that there are two very different issues involved: the film itself, and the wider context of war films, particularly with the anniversary of WWI throwing up many issues.

KAJAKI is, in the strictest sense, not really a war film sincere does not involve enemy combat, even though the Taliban soldiers are shown as a threat. One member of the three-man patrol sent out, steps on an anti-personal mine, probably left there during the Russian invasion of Afghanistan. His leg is blown up and his comrades send for help, which duly arrives. But there are more mines in the vicinity of the first explosion, and a series of gruesome explosions leave more soldiers seriously wounded before a helicopter finally arrives.

Shot in six weeks last summer in Jordan, no detail is spared in KAJAKI and one has to question the BBFC “15” certificate: the realism of the injuries shown is horrendous and demands an “18” rating. In the final credits we learn the fate of the real men involved, amongst them is one soldier who died in a subsequent tour in Afghanistan. Another is collecting money for a veteran’s charity, by parachuting, even though he is an amputee. Part of the proceeds from various pre-screenings is also going, deservedly, to a veteran’s charity. Well acted, photographed and directed, there is little criticism of the film on a pure professional level apart from the sometimes hard to understand dialects of some of the actors.

The real issue is that one cannot show any film about the Afghan war out of context: the Soviet Union was rightly condemned for its invasion of the country. But in spite of the action of the Taliban, the last Labour government’s decision to send British soldiers to Afghanistan (or Iraq for that matter), is at best a grave error of judgement, at worst the condonement of mass slaughter. The lack of public support for the wars in this country does not seem to worry the MPs who voted for them (or the media who covered the campaign) but for the soldiers who were led to believe that there was a just war to be fought, it is a continuing tragedy. Returning, they feel totally unappreciated and lack even the basic funds for their re-integration into society. Therefore, one cannot deal with these complex issues with a straightforward, one-to-one account of individual heroism (however commendable), that obviates the fundamental questions regarding British involvement in this war. And on a very real and pragmatic level one does not need to be a clairvoyant to see that the military engagement had to end at some point – leaving the Taliban in charge. KAJAKI occasionally demonstrates the nobler side of soldiering, but that does not absolve politicians and parts of the media from their guilt.

ON GENERAL RELEASE FROM 28 NOVEMBER 2014