Jean-Pierre Léaud (*1944) is widely known as the face of the French Nouvelle Vague. During his impressive career he made seven film with François Truffaut and eight with Jean-Luc Godard. But the indie directors of the 1990s have continued to fascinate him and more recently he has appeared in Aki Kaurismaki’s Le Havre (2011) and Ming-liang Tsai’s Face (2009) and the upcoming comedy from Walter Veltroni C’e Tempo (2019).

Leaud’s transition from juvenile hero to mature character actor is quite amazing: his performance as the dying Louis XIV in Albert Serra’s La Morte du Louis XIV (2016) is stunning, and the antithesis to his very beginnings. Whilst avoided the glitz of international stardom, he has enchanted six centuries of European filmmaking.

After his debut as Pierrot in Georges Lampin’s King on horseback (1958), he was to meet François Truffaut: an encounter which would change both their lives. The sly rebel, as Truffaut called himself, had met the revolutionary of the frontal attack. After filming wrapped on Les Quatre cents Coups (400 Blows) in 1959, Truffaut took charge of Léaud who was fast becoming a social outcast. The young man had been expelled from school, his parental home and a foster family. And this trauma feeds into the narrative of 400 Blows, a black-and-white hymn to adolescence. Léaud’s Antoine steals and lies his way through a drama which ends on the run-away Antoine facing the sea. It’s one of the most impressive finales in film history. The pairing of Truffaut and Léaud would manifest itself best in the Antoine Doinel trilogy – Baisers Volés (1968), Domicile Conjugal (1970) and L’Amour en fuite (1979), both men growing up together in a strange sort of way.

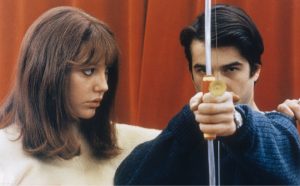

In 1966 Léaud would star in Godard’s Masculin, feminin: 15 Faits Précis, winning a Silver Bear for Best Actor at the Berlinale for his role as Paul, who is in a ménage-a-quatre with three women in a contemporary Paris. Loosely based on Maupassant’s short stories, this feature was the beginning of the break Godard would make with narrative cinema. Also called The Children of Marx and Coca Cola (an inter-title of the feature), sex and politics are at the core. Léaud is fragile, and the lighting shows him as beautiful and vulnerable as the three women, Madeleine (Chantal Goya), Catherine (Isabelle Duport) and Elisabeth (Marlene Jobert). All four main protagonists have very different plans for the future, when their agendas collide. There is immense elegance and beauty here (DoP Willy Kurant), and Godard treats his actors (perhaps for the last time) with more care than in the verbal politics of later films. Pauline Kael called it “that rare achievement: a work of grace in a contemporary setting” and for Andrew Sarris it was “the film of the season”.

In 1966 Léaud would star in Godard’s Masculin, feminin: 15 Faits Précis, winning a Silver Bear for Best Actor at the Berlinale for his role as Paul, who is in a ménage-a-quatre with three women in a contemporary Paris. Loosely based on Maupassant’s short stories, this feature was the beginning of the break Godard would make with narrative cinema. Also called The Children of Marx and Coca Cola (an inter-title of the feature), sex and politics are at the core. Léaud is fragile, and the lighting shows him as beautiful and vulnerable as the three women, Madeleine (Chantal Goya), Catherine (Isabelle Duport) and Elisabeth (Marlene Jobert). All four main protagonists have very different plans for the future, when their agendas collide. There is immense elegance and beauty here (DoP Willy Kurant), and Godard treats his actors (perhaps for the last time) with more care than in the verbal politics of later films. Pauline Kael called it “that rare achievement: a work of grace in a contemporary setting” and for Andrew Sarris it was “the film of the season”.

A year later Godard would cast Léaud as part of a group in La Chinoise (1967), this time surrounded by two women and two men, but with a very much harsher political focus. Based on Dostoyevsky’s The Possessed, this was Godard’s first adventure into Maoism. Léaud is Guillaume, in love with Veronique (Anne Wiazemsky), who has a much stronger personality than him, and will finally leave him. Kirilov (Lex de Bruijin), is the weakest of the trio and he will kill himself, as in the novel. Léaud’s Guillaume is in love with Veronique, but he is very much a man of clever words, but little action. Veronique on the other hand, is much braver, and decides in the end to assassinate the Russian Cultural minister on a visit to Paris. But he mixes up the numbers of his hotel room, and kills the wrong man. Wiazemsky, the grand daughter of novelist Andrew Malraux, then the Gaullist minister for Culture, fell in love with Godard, and the couple married after the shooting. As an in-joke, Godard casts Francis Jeanson in the film (Wiazemsky’s philosophy lecturer at the Paris 10 (Nanterre) University) having a debate with Veronique while on her way to assassinate the minister.

A year later Godard would cast Léaud as part of a group in La Chinoise (1967), this time surrounded by two women and two men, but with a very much harsher political focus. Based on Dostoyevsky’s The Possessed, this was Godard’s first adventure into Maoism. Léaud is Guillaume, in love with Veronique (Anne Wiazemsky), who has a much stronger personality than him, and will finally leave him. Kirilov (Lex de Bruijin), is the weakest of the trio and he will kill himself, as in the novel. Léaud’s Guillaume is in love with Veronique, but he is very much a man of clever words, but little action. Veronique on the other hand, is much braver, and decides in the end to assassinate the Russian Cultural minister on a visit to Paris. But he mixes up the numbers of his hotel room, and kills the wrong man. Wiazemsky, the grand daughter of novelist Andrew Malraux, then the Gaullist minister for Culture, fell in love with Godard, and the couple married after the shooting. As an in-joke, Godard casts Francis Jeanson in the film (Wiazemsky’s philosophy lecturer at the Paris 10 (Nanterre) University) having a debate with Veronique while on her way to assassinate the minister.

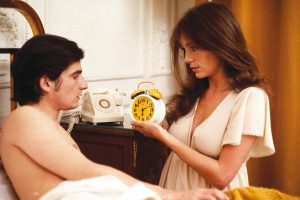

Pier Paolo Pasolino’s Porcile (1969) tells two parallel stories. The first is about a young cannibal who has killed his father. The second features Léaud as Julian Klotz, the son of German entrepreneur (Alberto Lionello), who is part of the German economic miracle after WWII. Julian’s fiancée Ida (Wiazemsky) is very much an early version of the Baader Meinhof Group, and tries in vain to agitate him. But Julian can’t stand people in general. He prefers the company of pigs, who will be his downfall. Léaud is again the angelic outsider, treating society with avoidance. He is so much more feminine than Ida, that the role reversal is quite breathtaking and Léaud carries his limited part with great sensitivity.

Truffaut’s 1973 outing La Nuit Americaine (Day for Night), is essentially about filmmaking, showing Léaud as the weak and self-obsessed actor Alphonse. During the filming of Je vous présente Pamela , a conventional weepie, he fancies leading lady Julie Baker (Jacqueline Bisset), who has recently had a breakdown. Out of pity she sleeps with him but Alphonse then ‘phones her analyst, Dr Nelson (David Markham), who has left his own family to live with her, and spills the beans on their fling. Léaud plays the histrionic weakling with great skill. And Truffaut, playing himself as the director, assumes the role of his protector – much as in real life. Godard, who by now had broken with his ex-friend Truffaut, called Day for Night “a big lie” – later the two founding fathers of the Nouvelle Vague fought over Léaud who somehow survived the acrimony and went on to work with another enfant terrible, Finnish director Aki Kaurismaki.

Truffaut’s 1973 outing La Nuit Americaine (Day for Night), is essentially about filmmaking, showing Léaud as the weak and self-obsessed actor Alphonse. During the filming of Je vous présente Pamela , a conventional weepie, he fancies leading lady Julie Baker (Jacqueline Bisset), who has recently had a breakdown. Out of pity she sleeps with him but Alphonse then ‘phones her analyst, Dr Nelson (David Markham), who has left his own family to live with her, and spills the beans on their fling. Léaud plays the histrionic weakling with great skill. And Truffaut, playing himself as the director, assumes the role of his protector – much as in real life. Godard, who by now had broken with his ex-friend Truffaut, called Day for Night “a big lie” – later the two founding fathers of the Nouvelle Vague fought over Léaud who somehow survived the acrimony and went on to work with another enfant terrible, Finnish director Aki Kaurismaki.

I hired a Contract Killer (1990) was one of Kaurismaki’s first English language films and he made a beeline for Léaud in the lead role. The gamine actor of Day for Night had since changed dramatically. His slight, almost feminine appearance was gone, and he’d put on a substantial amount of weight – his acting too was from another dimension. He plays Henri Boulanger, an English Civil Servant, who is sacked after fifteen years of service due to privatisation. With no life outside his work, he tries – in vain – to commit suicide. Then asks a contract killer (Kenneth Colley) to step in. But Margaret (Margi Clarke) gives his life a new meaning. With time running out, Henri tries to contact the killer, to reverse the order. Léaud is totally morbid and emotionally reduced, the environment is straight out of the 1950s, the colours pale, bleached out by wear and tear. Léaud’s agile friskiness has been replaced by gentle placidness, making him look much older than forty-six. But his acting had matured too, and he slips easily into character roles nobody would have expected from him in his New Wave days. AS

I hired a Contract Killer (1990) was one of Kaurismaki’s first English language films and he made a beeline for Léaud in the lead role. The gamine actor of Day for Night had since changed dramatically. His slight, almost feminine appearance was gone, and he’d put on a substantial amount of weight – his acting too was from another dimension. He plays Henri Boulanger, an English Civil Servant, who is sacked after fifteen years of service due to privatisation. With no life outside his work, he tries – in vain – to commit suicide. Then asks a contract killer (Kenneth Colley) to step in. But Margaret (Margi Clarke) gives his life a new meaning. With time running out, Henri tries to contact the killer, to reverse the order. Léaud is totally morbid and emotionally reduced, the environment is straight out of the 1950s, the colours pale, bleached out by wear and tear. Léaud’s agile friskiness has been replaced by gentle placidness, making him look much older than forty-six. But his acting had matured too, and he slips easily into character roles nobody would have expected from him in his New Wave days. AS

BERGAMO FILM MEETING | 9-17 MARCH 2019