George Clooney Lost the Bet

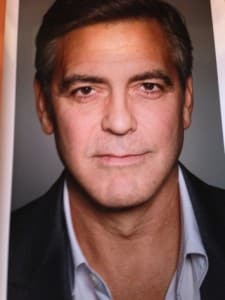

With the release of THE MONUMENTS MEN, Alex Barrett looks back at the Directing career of George Clooney

The story, such as it is, goes something like this: George Clooney never wanted to become a director. The script that was to become his debut feature, Confessions of a Dangerous Mind (2002), was due to be directed by, variously, Curtis Hanson, P. J. Hogan, David Fincher, Brian De Palma and Bryan Singer, with Clooney attached to act in a supporting role. When Singer departed, and the film collapsed once more, Clooney stepped up: the script, he said, was simply too great to be left languishing in development hell. So Clooney got to work, called in some favours, made the film, and bet Chuck Barris (on whose memoir Confessions is based) $10,000 that he wouldn’t make another film in the next five years – it really was, Clooney said, only the great script that made him want to direct the film.

The story, such as it is, goes something like this: George Clooney never wanted to become a director. The script that was to become his debut feature, Confessions of a Dangerous Mind (2002), was due to be directed by, variously, Curtis Hanson, P. J. Hogan, David Fincher, Brian De Palma and Bryan Singer, with Clooney attached to act in a supporting role. When Singer departed, and the film collapsed once more, Clooney stepped up: the script, he said, was simply too great to be left languishing in development hell. So Clooney got to work, called in some favours, made the film, and bet Chuck Barris (on whose memoir Confessions is based) $10,000 that he wouldn’t make another film in the next five years – it really was, Clooney said, only the great script that made him want to direct the film.

But the truth, perhaps, is a little more complicated. Charlie Kaufman, the writer of that ‘great script’, has publicly denounced the finished film, stating that Clooney ‘took’ the project from him and made something that little resembled the original screenplay.

Such stories are not unique to Kaufman and Confessions – five years later, Clooney would resign from the “Writers Guild of America” after the Guild refused to allow him a writing credit on his screwball sports comedy Leatherheads (2008), for which he claimed to have so significantly reworked the original screenplay that only two scenes remained intact. Also significantly changed was Beau Willimon’s Farragut North, which Clooney and his producing partner Grant Heslov brought to the screen as The Ides of March (2011) – though this time seemingly with the writer’s full collaboration and endorsement (Willimon shares the screenplay credit with Clooney and Heslov on the final film).

If Clooney’s reworking of scripts is far from the only constant that runs across his directorial work, it may well be a contributing factor to the other consistencies. The protagonists of his first four features, and his television series Unscripted (2005), are all driven individuals who wish to succeed at any cost, most of whom are seeking love, fame and fortune of some kind, and who have a reluctance to play by the rules. There is also a recurrence of characters who work in the media, television and journalism – often allowing for themes of integrity and honesty to emerge. If it’s possible to reduce this to biography (Clooney’s father, Nick Clooney, was a journalist, game show host and news reader), it’s also possible to see it as a tribute to the cinema of the past – for, lest we forget, it was ex-newspapermen like Ben Hecht and Herman J. Mankiewicz who wrote the films of Hollywood’s Golden Age, often placing reporters at the centre of their stories. Indeed, Clooney’s films exhibit a surprisingly level of cine-literacy, and in his audio commentaries he often talks openly about his references, and about ‘stealing’ ideas from other filmmakers.

To put all this another way: for someone who ‘never wanted to direct’, Clooney’s films display a surprising degree of consistency, despite their seemingly disparate genres and styles – and, in this, one can’t help but be reminded of Steven Soderbergh. One of Hollywood’s greatest polymaths and an acknowledged influence on Clooney’s direction, Soderbergh is, of course, also a close friend and frequent collaborator of both Clooney-the-actor and Clooney-the-director (Soderbergh served as Executive Producer on Confessions, Unscripted and Good Night, and Good Luck. (2005)). But if Soderbergh’s influence is often felt in Clooney-the-director’s work, it’s far from the only discernible impression left by those that have worked with Clooney-the-actor. The tone of Leatherheads, for instance, owes something to the work of the Coen Brothers, and it’s interesting to note that Clooney was working on the film’s script during the making of Intolerable Cruelty (2003), and was shooting the pickups while starring in Burn After Reading (2008). If nothing else, such impressions of influence remind us that Clooney has worked with, and learnt from, the best.

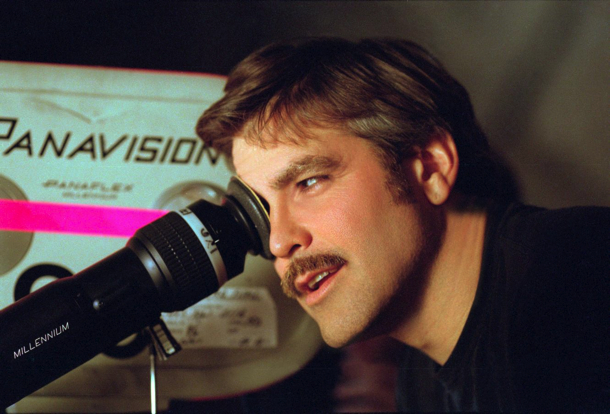

Although a notorious prankster, those who have worked with Clooney-the-director have commented on his focus and intelligence, and he is known for meticulously planning and storyboarding his films in advance. As a debut, Confessions was startlingly accomplished, already displaying an excellent grasp of four fundamental tenets of filmmaking: camera, story, sound and performance. An anarchic play with the conventions and tropes of biopics, the film finds a fascinating form for exploring an ambiguous mind. If that makes it sound like Clooney-the-director sprung fully formed from Clooney-the-actor, the looseness of Confessions nevertheless makes it feel like a film made by a director still finding his feet – which didn’t take long. With his second film, Good Night, and Good Luck., Clooney-the-director truly came into his own.

Although a notorious prankster, those who have worked with Clooney-the-director have commented on his focus and intelligence, and he is known for meticulously planning and storyboarding his films in advance. As a debut, Confessions was startlingly accomplished, already displaying an excellent grasp of four fundamental tenets of filmmaking: camera, story, sound and performance. An anarchic play with the conventions and tropes of biopics, the film finds a fascinating form for exploring an ambiguous mind. If that makes it sound like Clooney-the-director sprung fully formed from Clooney-the-actor, the looseness of Confessions nevertheless makes it feel like a film made by a director still finding his feet – which didn’t take long. With his second film, Good Night, and Good Luck., Clooney-the-director truly came into his own.

A riveting, claustrophobic account of broadcast journalist Edward R. Murrow’s outspoken reportage of Senator McCarthy’s anti-communist witch hunts, the film almost plays like an inverse of Confessions: where Confessions told of a globe-trotting anti-communist agent, Good Night is almost entirely confined to the studio in which Murrow railed against those combating the ‘red threat’; where Confessions was about a figure considered to be responsible for the decline of American television, Good Night is about a bastion of quality television. As if in recognition of his more serious, sombre subject, Clooney replaces the showy style of his debut with a calmer, more lyrical beauty (roaming, long-lens, shallow-depth photography may be a cliché of modern cinema, but rarely – if ever – has it been used so well). If it’s true that the film is undoubtedly in thrall to its subject, and no less editorialised than Murrow’s own work, it seems Clooney is taking a leaf from Murrow’s book, following his dictum that not every story has two sides: sometimes we must choose. McCarthy is left to defend himself in his own words, now as he did then, and the choice to use only real footage of McCarthy, rather than have an actor portray him, lends the film the authentic air of reportage. But there is real drama here too, and the film remains Clooney’s masterpiece. Simply put, it is in a different league from Confessions, and from the film that Clooney made next: Leatherheads.

But Leatherheads itself is no slouch, and certainly much better than its lacklustre reception suggests. Though it’s true that the speed and charm of its one liners never reaches screwball at its best, and that the film is occasionally derailed by moments of outright silliness, there are also moments of real beauty, and it’s never less than amusing and heartfelt. Clooney shot the film with no handheld camerawork, no steadicams, and nothing else that he considered stylistically ‘contemporary’. It’s an unashamed throwback, and one that is surprisingly dense and endearing.

For his forth film, The Ides of March, Clooney returned to the more serious, political register of Good Night. A tale of loyalty and betrayal set against the backdrop of a (fictional) Democratic primary election, the film takes its title from the day that Julius Caesar was murdered – and in doing so invokes Shakespeare. If the invocation feels like a stretch, it’s far from unwarranted: there’s no denying the power of Clooney’s terse and tense examination of political skulduggery. Moreover, Clooney should be commended both for once again daring to make a small-scale drama, and for once again showing how thrilling they can be (dramas, filmmakers are constantly told, don’t sell). So far, Clooney has alternated his dramas with comedies (his films neatly follow a comedy – serious – comedy – serious pattern, as if aping the classic ‘one for me, one for them’ formula), and this looks set to continue with the forthcoming release of his new comedy-drama The Monuments Men (2014).

Comedy was also a big part of his seemingly little seen and underappreciated HBO series Unscripted (Clooney directed five episodes of the ten-part series, the other five being helmed by Grant Heslov). Less broad than his other forays into comedy, the series fuses fact and fiction to present a quick-moving, naturalistic tapestry of the lives of three actors – Bryan Greenberg, Krista Allen and Jennifer Hall – who all play versions of themselves. Thrown into the mix is a superb Frank Langella as acting teacher Goddard Fulton – a pretentious, sleazy sage, if ever there was one. Shot in a low-fi, mumblecore-esque aesthetic, the series boasts cameos from a whole host of celebrities playing themselves, including Noah Wyle, Akiva Goldsman, Doug Liman, Brad Pitt, Angelina Jolie, Hank Azaria, Sam Mendes, Francis Lawrence, Shia LaBeouf, Danny Trejo, Brittany Murphy, Sam Rockwell, Meryl Streep and Uma Thurman, amongst others. As this roll-call perhaps suggests, there’s an impish mischievousness to the proceedings, and the end result is both a hilarious satire on the entrainment industry, and an engaging and addictive portrayal of the lives of actors, both struggling and successful. In fact, the show’s lack of wider recognition may be the biggest mystery of Clooney’s career, and while his continued interest in directing may have lost him his bet with Barris, it certainly feels like the world of modern Hollywood filmmaking is all the richer for it. ALEX BARRETT

THE MONUMENTS MEN IS ON GENERAL RELEASE FROM 14TH FEBRUARY 2014 NATIONWIDE