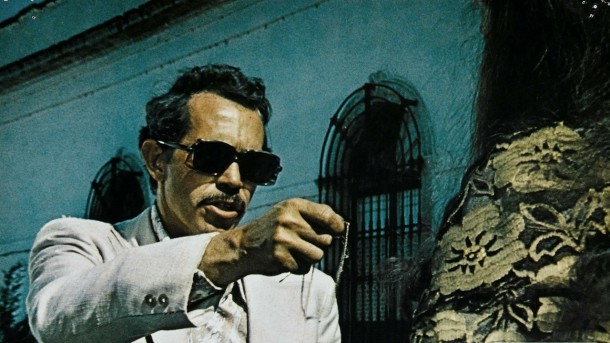

Dir.: Sam Peckinpah | Cast: Warren Oates, Isela Vega, Robert Webber, Gig Young, Kris Kristofferson, Emilio Fernandez, Janine Maldonado | USA/Mexico | 112 min.

Director Sam Peckinpah (1925-1984) brought us Straw Dogs and The Getaway and was not called “Bloody Sam” for nothing: after a rather studious beginning – he earned an MA in Drama – Peckinpah worked as an assistant to Don Siegel, and went on to direct 14 films, most of them ultra-violent with headcounts often running into double figures: BRING ME THE HEAD OF ALFREDO GARCIA ‘claimed’ 25 screen lives. The director – always at war with Hollywood and dependent on alcohol and drugs – was seen by critics and insiders as either a unrefined malcontent or a genius.

Bennie (Oates), a middle-aged drunkard and piano player in a seedy Mexican bar, is hired by Sappensly (Robert Webber), and Quill (Gig Young), two assassins, to find a certain Alfredo Garcia. Wanted ‘dead or alive’ by ‘El Jeffe’ (Fernandez), a rich cattle farmer, for impregnating his daughter Teresa (Maldonado), the price tag is a cool million Dollar. Bennie is in love with Elita (Vega), who, as it turns out, had an affair with Garcia, who had died recently in a drunk driving accident. Bennie is hell bent on finding his corps and separating the head, to bring it as proof to the two assassins. Elita warns him in vain (“we only need to be together”), but Bennie wants his “Dinero”, love alone is not enough for him. After the grisly decapitating act, Bennie not only loses the head, but also Elita, who is killed. Bennie regains the head from the men who killed Elita, but is soon confronted by the family of Garcia, who want revenge.

This is real macho stuff and Peckinpah doesn’t pull his punches or quail away from disrespecting the female of the species. It is not just the overkill of violence, which spoils many of Peckinpah’s films: his misogyny is really alarming. In one scene, Bennie and Elita are set upon by two bikers (Kris Kristofferson and Donnie Frits), who want to rape the woman. Bennie wants to intervene, but Elita, who is only interested in saving his life, is soon seen kissing the Kristofferson character passionately. Bennie shoots the two, and is appalled more with Elita than the two men.

DoP Alex Phillips jr., who shared with Peckinpah a dislike for wide angles, and the love for multiple camera-setups and zoom, has created awesome battlefield set pieces which would be at home in any war movie. But his close-ups of Bennie and Alfredo’s head are equally impressive: Bennie’s conversations with the head are proof of Peckinpah’s love for cruel perversity, as is the scene with El Jeffe, having his daughter stripped in front of his family, clergy and employees, breaking her arm with sadistic pleasure, to have her confess the name of her lover.

Peckinpah’s oeuvre has a wantonly repugnant quality, to call this spellbinding, as his defenders do, is giving his nastiness perhaps too much credit. The wretchedness of nearly all his characters is perhaps a projection of his own personality: he never seemed to be at peace with himself. The visually stunning mayhem is undoubtedly impressive – but the gutter philosophy going hand in hand with it, is often unbearable. AS