Director: Rolan Serhiienko

Cast: Iurii Dubroviv Iurii Nazarov

65min Drama Ukraine

Rolan Serhiienko’s 1968 feature debut is a poetic realist drama that explores a tragic episode of Ukrainian history. Using experiential ethnography to record the effects of the interwar process of collectivization on a family of peasant farmers in Ukraine, this sixties recollection of a time of chaos, widescale suffering and death is a lyrical example of ‘post-memorial’ cinema and offers valuable testament of Stalinism and its effects on the Ukrainian rural population during the 1920s and 30s.

After the Great War, the Soviet Union needed to service the burgeoning nutritional needs of its growing industrial population and these relied heavily on Ukraine’s role as ‘bread basket’ to feed the Bolshevik workers. So, under a policy of forced consolidation, land was collected from the peasant farmers, who owned and farmed it, and redistributed it into Soviet collectives, which would then farm the land under Stalinist run cooperatives known as “kolkhozes”, where strict new laws ensured that grain was handed over to the State. Naturally this rapid process of change and loss caused severe social trauma to the peasant farmers, many of whom preferred to slaughter their animals and eat them, rather than give up their property to the Government.

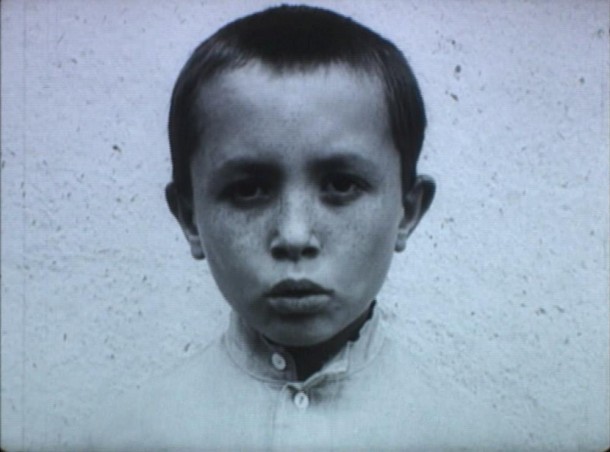

Based on the recollection of one man, seen from childhood to adulthood, Serhiienko tracks the soulful and desperate experience cinematically, making great use of Ukraine’s panoramic scenery: vast farmlands of swaying corn, orchards, endless country roads and, of course, the magnificent cloudscapes by which his father was able to forecast the weather which was so vital to the liveliehood of crops and animals alike. Soulful, sombre and occasionally sinister in tone: the brief euphoria of contributing collectively to the growth of the nation was rapidly eclipsed by widespread desperation of what enforced strategy implied.

Mykhailo Bielikov’s restless camera hurtles down endless roads to a distant past recording carts and farm animals in motion across the countryside, occasionally looking up from the roadside at passers-by and frequently focusing on local peasants who recount their memories in intimate moments, such as a young woman called Vustia, who eventually breaks down in tears as she reads from her bible. One particularly harrowing scene records a grandmother who appears to be travelling in the passenger seat of a car. In close-up, she talks of her memory of the past and village people she knew back then. But there is an unsettling feel to this scene, almost as if the POV is absent or perhaps a ghost. As the grandmother remembers individual villagers, the narrator explains how they have all died tragically. In Bili Khmary, Serhiienko recalls the pre-birth of cinema photography and how it replaced the Deguerrotype; of Eadweard Muybridge and Juliet Margaret Cameron. Expressionist and impressionist, there is a sense of kinesis that feels both intimate and otherworldly in style.

The past is often remembered with nostalgia as a time of fruitfulness, fecundity and abundance: long summers; beautiful young people; marriages and births; seeding of crops and fruit particularly, watermelons. But the after being forced to give up their land, often violently and under protest – the memories are of freezing winters, aching limbs, gnawing hunger, tiredness and time poverty. “We have no bread, what shall we feed the children?”

REVIEWED AS PART OF THE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON’S SCHOOL OF SLAVONIC AND EAST EUROPEAN STUDIES | BLOOMSBURY THEATRE IN CELEBRATION OF THEIR CENTENARY 1915 – 2015