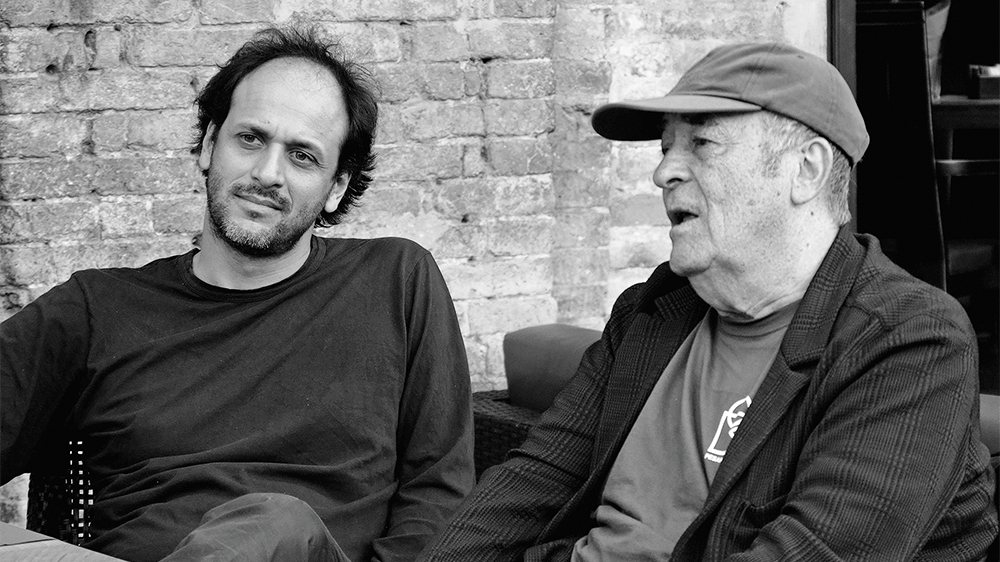

Dir.: Luca Guadagnino, Walter Fasano

Italy 2013, 105 min Documentary

This is much more than the sum of over 300 hours of documented interviews with Bernardo Bertolucci, it is an essay on the art of film making itself; and to a certain degree, the history of European filmmaking since the early sixties.

Bertolucci represented much more than Italian cinema. His close links with the French Nouvelle Vague are well-documented not only by his ruptured friendship with Jean-Luc Godard, but his insistence that the art of film making should be discussed in French, the birthplace of the Seventh Art. Needless to say, his French is impeccable; he could pass for a native. Whilst the filmography is handled more or less chronologically, the interviews themselves jump from topic to topic, and we can listen to Bertoluccci’s often changing views on his work, politics and personal life.

To start with, his relationship with his father Attilio was the inspiration for the young Bernardo: we see a scene from a prize-giving for poetry: Attilio is hiding from the camera, not wanting to steal the limelight from his young son. Later on his father says “you are a clever man, you have killed me over and over again, but only on film, so you stayed out of prison”. His relationship with his mother is not mentioned in length, but the discussion about La Luna answers these questions. Early influences were Rossellini and Fellini; after seeing the latter’s La Dolce Vita, BB decided to convert from poetry to film- making. Seeing Fellini’s remarkable skill: the Via Veneto was a boring street where nothing happened until the excitement of Fellini’s film transformed the banal into something magical – Bertolucci was inspired.

The transformation from the bourgeois poet to the Marxist revolutionary is documented by Before the Revolution and BB’s friendship with Pier Paolo Pasolini, whom he met as a friend of his father. (He was assistant to Pasolini for Accatone). Bertolucci is quiet cagey about Maria Schneider’s accusation regarding Last Tango in Paris, but he sees himself more of a victim than a wrong-doer. The scandal seems to have lingered on in Italy. Twenty years later a relative of Giuseppe Verdi tried to kill BB in his car, when the director was filming outside Verdi’s villa, shouting: “You have no right to be here, you are a Marxist pornographer”.

His masterpiece 1900 was for him also “a poem about the countryside where I grew up”, even though he and others thought at the time that “they had sold the ruling class the rope with which they would hang them”; a reference to the exorbitant cost for an openly Marxist film financed by a major Hollywood studio. Undoubtedly, Bertolucci has had a full and fascinating innings thus far: Guadagnino almost bites off more than here can chew here: the meeting with the Dalai Lama, his three operations on a slipped disc, which ended with him being unable to use his legs any more, the long creative pause between Dreamers (2003) and his last film Me and You (2012), which he shot from the wheelchair.

Apart from the lack of images showing the director at work, our enjoyment and engagement with the film is somewhat reduced by the interviews being nearly all in French and Italian, making the not so polyglot viewer focus on the subtitles rather than on the images of this extraordinary talent. Andre Simonoviesz

BERNARDO BERTOLUCCI 1941-2018