Dir: Alexandre O. Philippe | Biopic 2025 76 min

Reviewed by Peter Herbert

Kim Novak’s Vertigo might also be described as Kim Novak’s Eyes as the film opens and closes with a look into the eyes of an enduring and resilient legend.

More a love letter to an American beauty rather than a traditional biopic of a Hollywood actress, Kim Novak’s Vertigo is a mirror held up to the heart and mind of Kim Novak, gaining depth from a bond created between Kim Novak and filmmaker Alexandre O. Philippe who has explored the craft of film directors including David Lynch and William Freidkin.

The focus here is on the actress as a tool for the filmmaker.Transcribed from a filmed interview, the film begins with a general sketch of early family life and how Marilyn Novak was first seen in a chorus line in the Jane Russell musical The French Line in 1954. Her meteoric rise the following year as Kim Novak also triggered her reaction against Columbia Picture’s superficial projection of Novak as a conveyor belt blonde bombshell which was a market place for Hollywood and the media in the 1950’s.

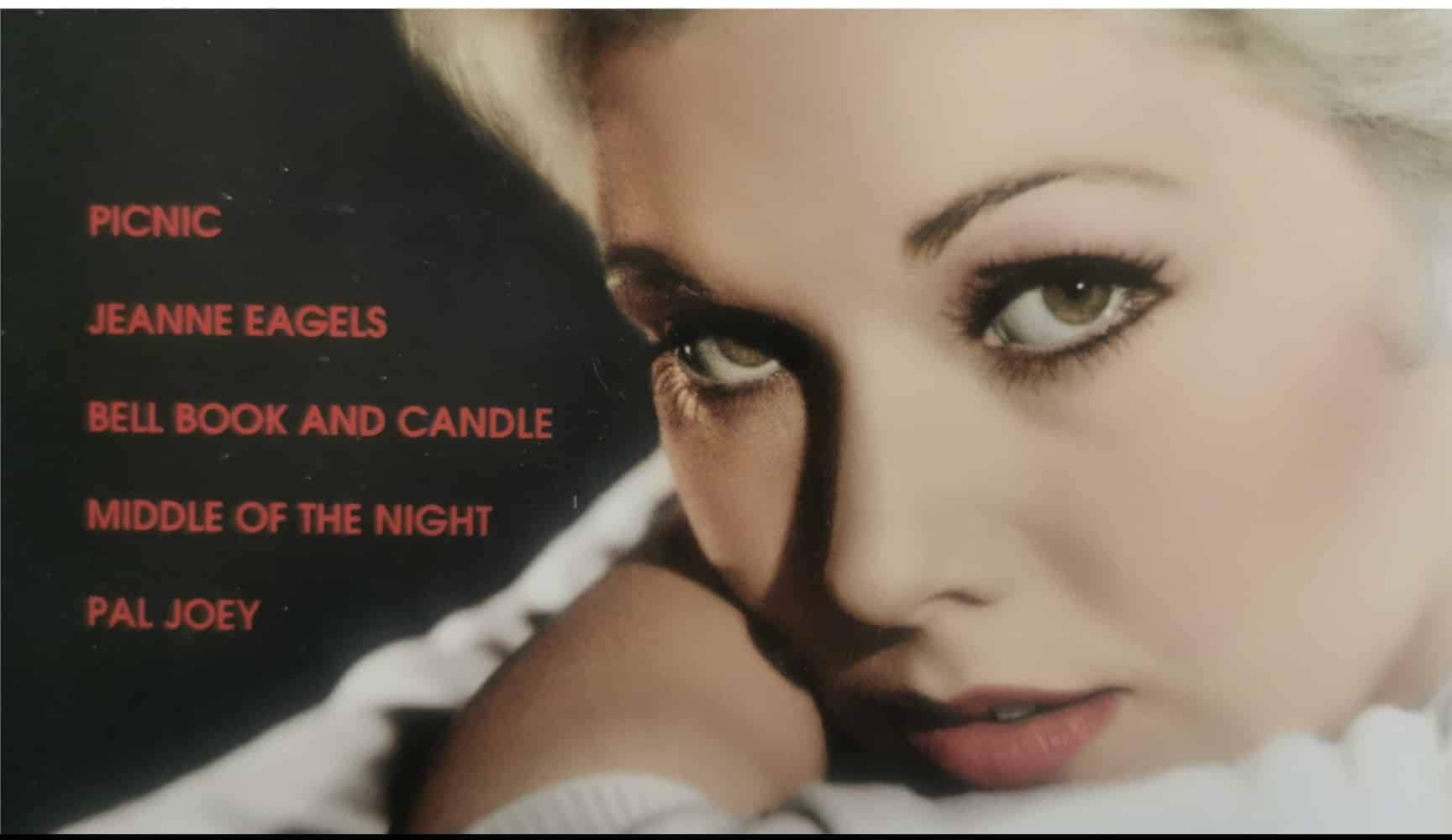

What the actress wanted, very early on, was respect as a woman in charge of her own destiny or captain of her own ship, as she describes in the interview. She would soon get this by receiving key roles in a group of important films in the mid to late 50s including Hitchcock’s Vertigo in 1958. The constant fight particularly in the 1960s between her star power and the machine that fuels this resulted in Novak choosing to walk away from Hollywood on her own terms.

This happened to Greta Garbo decades earlier and the parallel between Garbo and Novak as survivors of the Hollywood system are beautifully and sensitively explored by O. Philippe with film extract montages exploring how the passive nature of ethereal beauty is created for the camera eye.

The film does not go into documented incidents including an interracial relationship with Sammy Davis Jnr during the racism of 1950s America or the clashes with Columbia mogul Harry Cohn who was quoted as telling Novak she was ‘nothing but a piece of meat’.

There is very little about marriages, relationships with key directors (Billy Wilder, Joshua Logan, Otto Preminger) or reported clashes with directors Henry Hathaway (Of Human Bondage 1964) and Mike Figgis (her final film Liebestraum in 1991).

There are more references to working with Hitchcock, although no specific mention of her most empathetic director George Sidney who could see a troubled feeling of passive alienation beneath the swan like beauty. Novak admits that she loved director Richard Quine for whom she would shine in both Bell Book and Candle (1957) and Strangers When We Meet (1960). As with Novak, Quine suffered from depression which would end his life in 1989.

The film is effective focusing on the inner turmoil of performances with a beautiful extract from Delbert Mann’s Middle Of The Night (1959) revealing her self-doubt and confusions. Robert Aldrich’s The Legend of Lylah Clare (1968) provides a scathing mock parody of Novak’s fight with stardom and most striking are extracts from the uncompromising Jeanne Eagles (1957).

In this far from conventional bio pic, George Sidney coaxed out of Novak the sublime moods of another troubled soul from the back pages of the late silent and early sound days of Hollywood. Sidney will also film Novak using an overhead camera as she moves across a room after overdosing on drugs, with a sense of the graceful physical movement Cukor captured while filming Garbo in Camille.

Novak was also a survivor, like Garbo, and in this late life documentary essay there is much to enjoy. This includes Novak’s skill as a painter with artwork that frequently portrays a colour filled vortex of movement which echo visual motifs linked to Vertigo.

There is a beautiful reference to how she felt about James Stewart’s naked feet in Bell Book and Candle and after unpacking a box from her loft, Novak lovingly remembers, touches and smells the suited dress jacket she once wore in Vertigo. A private letter from her father reveals more fatherly love than she remembered, while photos of her love of animals, riding horses and a life far away from the madding crowd are all offset by an admission that growing old is not easy.

Aged 92 when the interview was filmed, and lit by Robert Muratore with sensitive care, Novak admits she is near the end of her time. A writer once commented If you are blind to or have no time for the 1001 beauties of George Sidney’s Jeanne Eagles then don’t even bother to look any further. It might be useful to add that a look into the eyes of Kim Novak as provided by this delightful film could well be the answer. Peter Herbert

NOW SCREENING AT BFI LONDON FILM FESTIVAL 2025