Dir.: Cyril Leuthy; Narrator Guillaume Goux; with Anna Karina, Marina Vlady, Anne Wiazemski, Hanna Schigulla, Judy Delphi, Jean-Pierre Gorin, Mirelle Darc, Daniel Cohn Bendit and JL Godard; France 2022, 100 min.

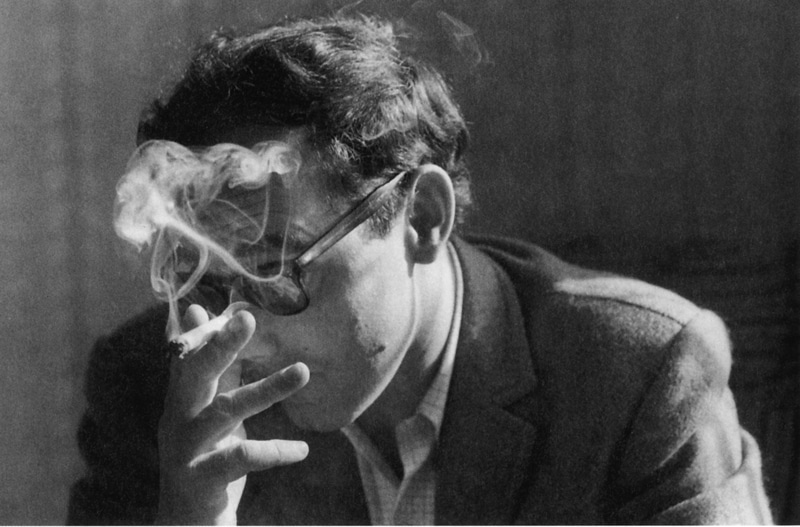

Jean-Luc Godard (1930-2022) was still out to revolutionise cinema, just before his death at 91, according to this latest documentary about the famous filmmaker and co-founder of the Nouvelle Vague who claims, in his defence “I don’t have my heart in my mouth anymore”.

“Godard is a legend, but we have forgotten the man”. In trying to uncover the real Jean-Luc director Cyril Leuthy sat down with Godard’s many collaborators, friends and critics who have a lot to say about an eternal rebel who was still exhausting himself in the hunt for a perfect cinema, even with 140 films under his belt.

We watch him on the set of Le Mepris in 1963, and in scenes from Breathless, for which Godard won the Prix Jean Vigo. At the ceremony he claimed: “awards matter, because they draw attention to the cinema”. The film changed society and the world (!), everything was possible from then on, even close-ups with a wide-angle shot.

Godard was born in a fashionable Paris district in 1930 and moved between Paris and Switzerland as a young man. His father Paul was a physician. His mother Odile worked for a bank, and died in an accident in 1954. The family did not want JLG to attend her funeral, since he had disgraced himself by stealing from his friends and family: he financed Rivette’s first film with the money he stole from his uncles. After the success of his first feature, Godard was happy that Le Petit Soldat (1960) was banned. “I am happy that my second film is hated, it brings me closer to the cinema”. Marina Vlady, star of Godard’s “Two or three things I know about her” believes he actually played the improvising genius. In reality, Vlady and the cast were dependent on their earphones: Godard directing them “like robots”.

Anna Karina, JLG’s first wife and muse is adamant: “he was irritated by happiness. He is pure spirit”. Macha Meril, who starred in JLGs Une femme mariee (1964) goes a step further: “I was like a substitute for Anna Karina. He treated me like an ornithological object”. Anne Wiazemsky, wife number two, was proud to be with the filmmaker, but also found JLG soft, funny and loving. Her recollections of her marriage are read out by a child. But after she starred in La Chinoise, the first cracks appeared. Daniel Cohn-Bendit claims the Chinese employees of the Paris embassy called JLG a moron, and would have forbidden the film title, had they had the power. Cohn-Bendit maintains Godard supported the Cultural Revolution, which the former calls “Ritual slaughters” JLG meanwhile was fighting the De Gaulle regime, calling democracy ‘a slow way of death’.

From then on JLG put his anger onto the big screen: Weekend (1967) saw mass slaughter on the auto routes of France, a metaphor for France’s capitalist take-down. After helping to support the re-instatement of Henri Langlois as leader of the Cinematheque, Godard and Truffaut helped to bring the 1968 Cannes Festival to an abrupt standstill. But the intended revolution did not materialise. JLG fled into the Dziga Vertov collective, co-lead by Jean-Pierre Gori. And Anne Wiazemsky, moved out: “Gorin moved in with JLG, there was no room for me. I loved him as a filmmaker, not a commissar.”.

The features that followed in the aftermath: Vent d’ Est and Vladimir and Rosa, had limited releases – and remained in the dark for decades. Their financing had only been raised because JLG was behind the camera, even though he was part of the collective. Godard then retreated into the political cinema of the 1970s. In 1977 he went to live in Rolle, Switzerland, where he had spent his childhood.

A near fatal accident saw him teaming up with a friend from the past Anne-Marie Miéville. After the two moved to Grenoble, Godard founded his first studio ‘Sonimege’. But he still dreamed of starting again: “When I take a shot, I ask myself, what would Lang, Renoir or Hitchcock do? And I would do exactly the opposite”. Still, Sauve qui Peut (1980) was a new beginning, JLG used the word ‘I’ for the first time in a decade. Cannes was helpful for his comeback, and he lectured “the incredible is what we don’t see”. Passion (1982) with Hanna Schygulla was another step towards rehabilitation. Her remark “the only relationship he has is when he is filming” is the nearest anyone has got to the truth.

In 1983 JLG won the Golden Lion in Venice – it also got him a pie in the face when a member of the audience was unhappy with the sexual content of the feature. In 1995, the first snap of JLG as a child was discovered. In the photo, he was actually mourning himself. ” I mourned first, but death did not come. Since then I follow myself as a human being, but I am not one”. His major epic Histoires du Cinema, cost him ten years of his life and was finally released in 1988, with a running time of 423 minutes. Based on 495 films and 148 books, plus photographs and paintings, it sums up his philosophy: “History has to be told in ruins, cinema is only real as a history of ruins”.

And finally: “Cinema is nothing. but it wants everything”. And we can be sure that JLG has given himself, or whatever is left of him, to the beast called cinema. DoP Gertrude Baillot sets a frenetic tempo in motion – and it never slackens. Leuthy has succeeded in bringing the personal and the cinematographical together in a portrait of a man who sacrificed his own life and ability to love on the alter of re-invention – without ever finding himself in the process. AS

JEAN LUC GODARD 1930-2022 | VENICE FILM FESTIVAL | VENICE CLASSICS 2022