Bergamo Film Meeting this year celebrates the work of Jonas Mekas, who died aged 96 in January this year. An avant-garde filmmaker in the true sense of the word he was also one of the influential figures in American underground cinema and made his name there in the late 1950s, founding and writing for the film magazine Film Culture. Along with the publication Village Voice there was an interplay between European avant-garde with the US Beat movement of the era and Mekas nurtured the most radical film voices in New York City.

Mekas’ roots were in Lituania where he was born in the village of Semeniškiai. But his film career was to be born out of adversity. During the final years of the Nazi occupation he was taken with his brother Adolfas to a labour camp in Germany whence they escaped into Denmark hiding out until the war ended. The two then spend four years in a refugee camp where their interest in cinema was kindled, watching classic films provided by the US forces. They both realised that their war experiences were of valuable interest and channeled their budding talent into writing scripts and eventually making their own films.

Despite this difficult start in life, Mekas was lucky enough to study at the University of Mainz, quite a privilege back in those days where many lost their studying opportunities due to conscription and the war effort in general. Luck also played a hand in sending Mekas to America with Adolfas, courtesy of the UN. Fetching up in Brooklyn in the late 1940s he bought his first 16mm camera, a Bolex, and started his life’s work. His first 35mm feature, Gun of the Trees (1961), was a politically infused indie drama ‘starring’ Adolfas and exploring the first knockings of Beat through the lives of four characters.

Commercially, his work mostly failed to attracted attention from distributors so he set about co-founding the New American Cinema Group and the Filmmakers’ Cooperative in 1962. Again this was a counter-culture initiative, upping the ante against mainstream cinema which he decried as being “boring”. His films were often screened in venues such as the Bleecker Street cinema in Greenwich Village. While distributors shied away from his work, the authorities did not. In 1964, he found himself charged with obscenity offences for screening Jean Genet’s gay film: Un Chant d’Amour.

His next experimental endeavour was a documentary called The Brig (1964) which looked at life in a Marine corps jail in Japan. By the late 1960s his gaze was also drifting towards a cinematic chronicle entitled Diaries, Notes and Sketches (1969) which featured luminaries such as Nico, Edie Sedgewick, Andy Warhol, Norman Mailer and even John Lennon and the Velvet Underground. Contrary to popular belief, Mekas was not gay himself – well, he may have swung both ways – in 1974 he married and sired a son Sebastian and a daughter Oona, with Hollis Melton.

His next project was an auto-biopic Lost, Lost, Lost (1976) that focused on his early years in America where he felt somewhat of an outsider despite his binding friendships with his fellow arthouse crowd. Paradise Not Yet Lost (1980) followed along similar lines and – some would say – his masterpiece As I Was Moving Ahead Occasionally I Saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty (2000), was an attempt to engage the audience in a lengthy look into his personal life, very much focusing on the act of film-making as much as the subject matter itself. He emerges a voyeur rather than a director as such. Recording his own life story, and distilling the events onto film, keeping a naturalistic approach at all times. And he was pleased with the results. Out-takes from the Life of a Happy Man (2012) seems to be a testament to contentment. MT

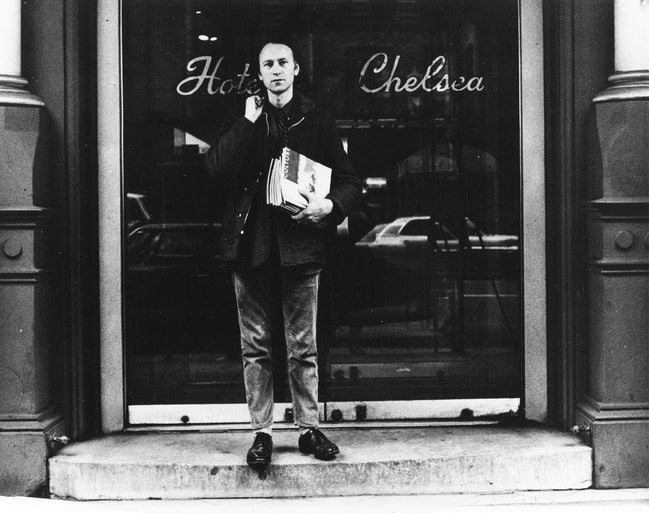

TRIBUTE to Jonas Mekas | Bergamo Film MEETING 2019