In 1964, Henri Georges Clouzot, the acclaimed director of thriller masterpieces Les Diaboliques and Wages of Fear, began work on his most ambitious film yet. Richard Chatten looks back at his unfinished work INFERNO (L’ENFER) and the documentary that emerged 45 years later.

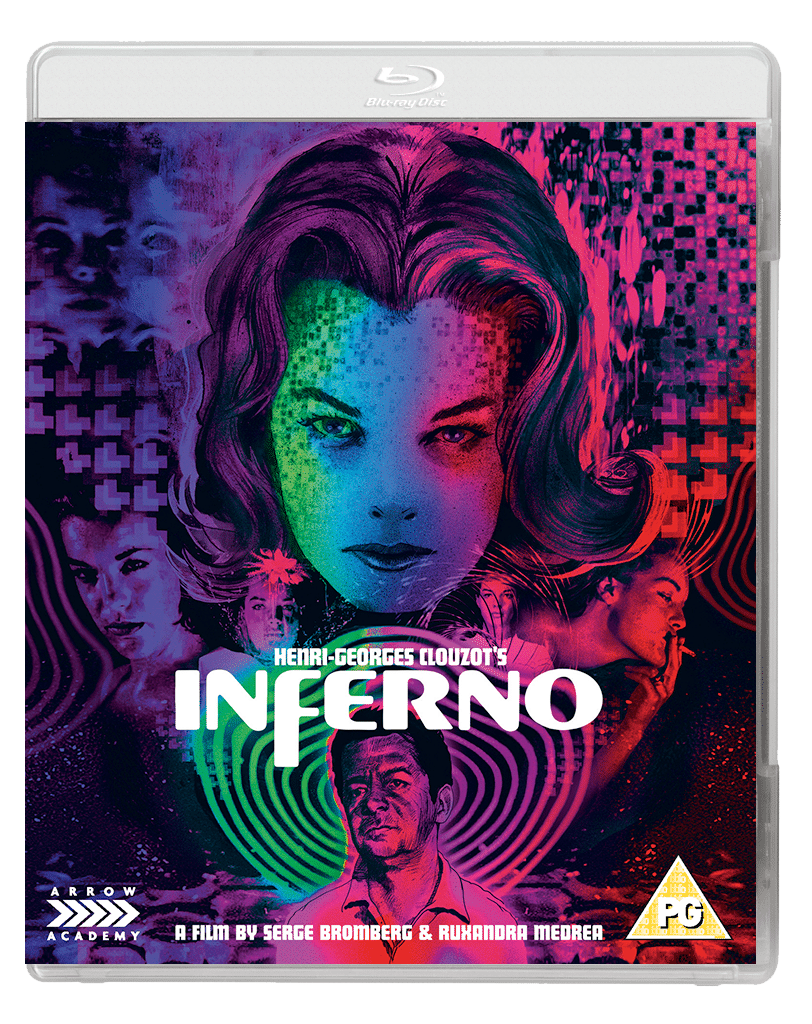

Dir: Serge Bromberg and Ruxandra Medrea | Cast: Romy Schneider, Serge Reggiani, Costa Gavras | 96′ | DOC

Like many other fields of human endeavour, the intricacies of the filmmaking process are often seen at their clearest when things go wrong, as has already been revealed in the fascinating documentaries, The Epic That Never Was (1965), about Josef Von Sternberg’s 1937 attempt to film I Claudius, and Lost in La Mancha (2002) about Terry Gilliam’s abortive The Man Who Killed Don Quixote in 2000.

Another such blighted project was Henri-Georges Clouzot’s L’Enfer (literally Hell), on which the plug was pulled in 1964, leaving behind 185 cans of film (about 13 hours) around which 45 years later Serge Bromberg and Ruxandra Medrea assembled this remarkable documentary.

Known to have been a drama about an insanely jealous husband featuring Romy Schneider and shot in both black & white and colour (as indeed had Clouzot’s classic documentary Le Mystère Picasso in 1956), that was about all that was known about the film until Claude Chabrol filmed Clouzot’s original script in 1994, which revealed a plot about the proprietor of a lakeside hotel (played in Chabrol’s version by François Cluzet) who becomes unhinged through jealousy in a fashion similar to Bunuel’s El (1953) and Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut (1999).

Clouzot (1907-1977) had been a gifted director with a mean streak a mile wide (frequently evident in his films) whose earlier and later years had been plagued by health problems (mental as well as physical). His most recent film, La Vérité (1960) with Brigitte Bardot had a been a critical and commercial hit and Columbia wrote Clouzot a blank cheque for this next projected film with Romy Schneider anticipating that Clouzot would enjoy equivalent success with Miss Schneider as he had had with Bardot. Unfortunately, while La Vérité had had the firm hand of producer Raoul Lévy on the tiller, Clouzot took the responsibility upon himself of producing L’Enfer and ran wild with both time and money, shooting hours and hours of bizarre ‘psychological’ colour tests while driving his cast and crew mad on location in Auvergne until after just 10 days in July 1964 his star Serge Reggiani walked out after being forced repeatedly to run behind a camera car along the side of a lake. Clouzot shortly afterwards suffered a heart attack that provided the pretext to pull the plug on a production that had run hopelessly out of control.

The existing footage in Dayglo colours that he left behind – much of it Miss Schneider, including her water-skiing in blue lipstick – is absolutely eye-popping (plenty of it not surprisingly has become popular on YouTube), but suggests he was more interested in them than in delivering a coherent narrative, portions of which also exist in black & white. Clouzot’s sole subsequent completed feature, La Prisonnière (1968) was a sadomasochistic drama also in pop-art colours (also known as Woman in Chains) that suggests how L’Enfer might have turned out had it been completed, and is ironically largely forgotten today.

Regrets that it may have been an unrealised masterpiece clouded the judgement of critics when they reviewed Chabrol’s version of 1994, and Chabrol ruefully observed that plenty of films have been unfavourably compared to earlier versions that had been made, but this must have been the first to be unfavourably compared to an earlier version that was never made! The two films would make a good two-disc box set, since the documentary makes much more sense if one has the grasp of the plot afforded by Chabrol’s version (which unfolds in straight linear sequence, whereas Clouzot’s film was going to be told in flashback); and watching Chabrol’s film the scene of Cluzet running alongside the lake now carries considerable additional dramatic impact as one experiences the thrill of recognition of finally seeing in its intended context what we saw poor Reggiani forced to do again and again thirty years earlier. @Richard Chatten

NOW AVAILABLE ON BLURAY COURTESY OF ARROW ACADEMY | MUBI