LOCARNO FILM FESTIVAL is celebrating its 70th Anniversary with a feline, canine and fantasy theme leading up to the the real mystery – who will win the coveted GOLDEN LEOPARD? There’s a surreal feel to this special edition with Isabelle Huppert struck by lightening in MADAME HYDE, a man who turns into a dog in Vanessa Paradis’ latest film CHIEN and of course the fabulous JACQUES TOURNEUR retrospective with a chance to see CAT PEOPLE (1942); THE LEOPARD MAN and I WALKED WITH A ZOMBIE (1943) in the Grand Piazza which seats 8,000 cinema-goers – Europe’s largest screening venue.

LOCARNO FILM FESTIVAL is celebrating its 70th Anniversary with a feline, canine and fantasy theme leading up to the the real mystery – who will win the coveted GOLDEN LEOPARD? There’s a surreal feel to this special edition with Isabelle Huppert struck by lightening in MADAME HYDE, a man who turns into a dog in Vanessa Paradis’ latest film CHIEN and of course the fabulous JACQUES TOURNEUR retrospective with a chance to see CAT PEOPLE (1942); THE LEOPARD MAN and I WALKED WITH A ZOMBIE (1943) in the Grand Piazza which seats 8,000 cinema-goers – Europe’s largest screening venue.

While Jacques Tourneur clearly had a feel for the surreal and a penchant for the macabre, he was not very fond of his four French features, shot between 1931 and 1934: “All those films are mixed up with each other in my mind. They resemble each other so much! It was always the same formula: musical, happy, young.” This is certainly true for Tout Ça Ne Vaut pas l’Amour; Pour Être Aimé and Toto but Les Filles de la Concierge (1934) is a brilliant character milieu study of a concierge. Madame Leclercq is the titular heroine who wants the best for her three daughters, whatever the circumstances. She even ‘rents’ one, Ginettte, to a wealthy suitor, but the ‘happy end’ justifies her method. Les Filles must have had some impact on Tourneur because, thirty years later, he expressed the desire to remake the film: “One could make a marvellous film out of it. People don’t make enough films about concierges, they’re an amazing group.” Indeed, where would be without Carlton, Your Doorman, the legendary concierge in TV hit Rhoda?.

While Jacques Tourneur clearly had a feel for the surreal and a penchant for the macabre, he was not very fond of his four French features, shot between 1931 and 1934: “All those films are mixed up with each other in my mind. They resemble each other so much! It was always the same formula: musical, happy, young.” This is certainly true for Tout Ça Ne Vaut pas l’Amour; Pour Être Aimé and Toto but Les Filles de la Concierge (1934) is a brilliant character milieu study of a concierge. Madame Leclercq is the titular heroine who wants the best for her three daughters, whatever the circumstances. She even ‘rents’ one, Ginettte, to a wealthy suitor, but the ‘happy end’ justifies her method. Les Filles must have had some impact on Tourneur because, thirty years later, he expressed the desire to remake the film: “One could make a marvellous film out of it. People don’t make enough films about concierges, they’re an amazing group.” Indeed, where would be without Carlton, Your Doorman, the legendary concierge in TV hit Rhoda?.

In 1934 Jacques Tourneur returned to Hollywood to work as a Second Unit director at MGM, where he also directed twenty short films. The most interesting of the shorts are Romance of Radium (1937), where the director takes us on a forty-year journey through the discovery process of what would become nuclear power, in just ten minutes! Part historical drama, impersonal chronicle and staged ‘docu-drama’, Romance is very dense; the treatment of the source as something “outside” of our world – it is clearly an early version of Experiment Perilous. What do You Think (1937) is a haunted house mystery, with the plot, structured like a Chinese mystery box, stretching out into the past, and the studios of Hollywood. It is certainly as obsessive as many of Tourneur’s features.

In 1934 Jacques Tourneur returned to Hollywood to work as a Second Unit director at MGM, where he also directed twenty short films. The most interesting of the shorts are Romance of Radium (1937), where the director takes us on a forty-year journey through the discovery process of what would become nuclear power, in just ten minutes! Part historical drama, impersonal chronicle and staged ‘docu-drama’, Romance is very dense; the treatment of the source as something “outside” of our world – it is clearly an early version of Experiment Perilous. What do You Think (1937) is a haunted house mystery, with the plot, structured like a Chinese mystery box, stretching out into the past, and the studios of Hollywood. It is certainly as obsessive as many of Tourneur’s features.

THEY ALL COME OUT (1939), Tourneur’s first feature in Hollywood, was first planned as a two-reel segment for a “Crime does not Pay” series of short films. It follows rather conventional lines (Bank heist and prison rehab), and, is visually satisfying, thanks to a very mobile camera, but its structure suffers from the late embellishment of the narrative.

Tourneur’s next projects for MGM were two Nick Carter features, MASTER DETECTIVE (1939) and PHANTOM RIDERS (1940). As Chris Fujiwara (who will present the retro) puts it: “Master Detective” is quicker and more immediately striking, but Phantom Riders has more in common visually with Tourneur’s later films. If MASTER DETECTIVE looks back to Tourneur’s past with its skilful interweaving of documentary and fiction, PHANTOM RIDERS anticipates the future with its sustaining of mood through rich décor and careful lighting; its low-budget exoticism; and its hint of thwarted sexuality”. But Tourneur really hated DOCTORS DON’T TELL (1941): “I detest this film, it is my worst”. All one can add, is that Doctors is really the most ‘un-Tourneresque’ feature of his career: it is bad, even for a routine film, its banality stupefying.

So after dabbling in the art of filmmaking in the 1930s, Jacques Tourneur’s most important features were to follow during the 1940s. In 1942, Val Lewton, who worked with Tourneur on the Second Unit for A Tale of Two Cities (1935), joined RKO as the new head for B-Horror films. His first project was CAT PEOPLE (1942) directed by Tourneur; the duo would go on to create I WALKED WITH A ZOMBIE and THE LEOPARD MAN in 1943 for RKO, before the studio made them go their separate ways with Tourneur commenting: “We were making so much money together that the studio said, we’ll make twice as much money, if we separate them”.

So after dabbling in the art of filmmaking in the 1930s, Jacques Tourneur’s most important features were to follow during the 1940s. In 1942, Val Lewton, who worked with Tourneur on the Second Unit for A Tale of Two Cities (1935), joined RKO as the new head for B-Horror films. His first project was CAT PEOPLE (1942) directed by Tourneur; the duo would go on to create I WALKED WITH A ZOMBIE and THE LEOPARD MAN in 1943 for RKO, before the studio made them go their separate ways with Tourneur commenting: “We were making so much money together that the studio said, we’ll make twice as much money, if we separate them”.

I WALKED WITH A ZOMBIE (1943) went into production just two months after CAT PEOPLE, before the surprisingly successful release of Tourneur’s first RKO feature. Trying to decribe Zombie is not an easy task because Tourneur blurred the border between reality and phantasy in his narrative. Betsy Connell (France s Dee), a Canadian nurse, takes care of Jessica (Christine Gordon) on the West Indian island of St. Sebastian. Jessica is married to the sugar planter Paul Holland (Tom Conway). She falls in love with Paul’s half-brother Wesley (James Ellison). After a scene with her husband, she falls into a trauma, and after several attempts of ‘curing’ her, Mrs. Rand (Edith Barnett), Paul and Wesley’s mother confesses that she has cast a voodoo spell on Jessica for bringing the family into disrepute. Wesley finally kills Jessica, to set her free. Tourneur preferred Zombie to Cat People, and often cited it as his favourite film. Zombie is Tourneur’s purest film when it comes to cinematic poetry, combining sounds and images into a “power of suggestion”, enhanced by the film’s narrative, which is full of enigma and contradiction, eluding any attempt to interpret it in a linear way. Zombie “is a sustained exercise in uncompromising ambiguity. Perfecting the formula that Lewton and Tourneur had developed in Cat People, the film carries its predecessor’s elliptical, oblique narrative procedures to astonishing extremes. The dialogue is almost nothing but a commentary on past events, obsessively revisiting itself, finally giving up the struggle and surrendering to a mute acceptance of the inexplicable. We watch the slow, atmospheric, lovingly detailed scenes with delight and fascination, realising at the end, that we have seen nothing but the traces of a conflict decided in advance.” (Chris Fujiwara).

s Dee), a Canadian nurse, takes care of Jessica (Christine Gordon) on the West Indian island of St. Sebastian. Jessica is married to the sugar planter Paul Holland (Tom Conway). She falls in love with Paul’s half-brother Wesley (James Ellison). After a scene with her husband, she falls into a trauma, and after several attempts of ‘curing’ her, Mrs. Rand (Edith Barnett), Paul and Wesley’s mother confesses that she has cast a voodoo spell on Jessica for bringing the family into disrepute. Wesley finally kills Jessica, to set her free. Tourneur preferred Zombie to Cat People, and often cited it as his favourite film. Zombie is Tourneur’s purest film when it comes to cinematic poetry, combining sounds and images into a “power of suggestion”, enhanced by the film’s narrative, which is full of enigma and contradiction, eluding any attempt to interpret it in a linear way. Zombie “is a sustained exercise in uncompromising ambiguity. Perfecting the formula that Lewton and Tourneur had developed in Cat People, the film carries its predecessor’s elliptical, oblique narrative procedures to astonishing extremes. The dialogue is almost nothing but a commentary on past events, obsessively revisiting itself, finally giving up the struggle and surrendering to a mute acceptance of the inexplicable. We watch the slow, atmospheric, lovingly detailed scenes with delight and fascination, realising at the end, that we have seen nothing but the traces of a conflict decided in advance.” (Chris Fujiwara).

THE LEOPARD MAN (1943) is seen, perhaps wrongly, as the weakest of the Lewton/Tourneur collaborations. Based on the novel by Cornel Woolrich (Rear Window), The Leopard Man is set in the nightclub milieu of New Mexico, where club owner Dennis O’Keefe (Jerry Manning) finds a leopard for his girl friend Kiki (Jean Brooks) to perform on the stage of his club. Kiki’s jealous competitor, Clo-clo (Margo), sets the leopard free and becomes one of his – presumed – three victims. Nevertheless, O’Keefe and Kiki suspect, that the leopard is only used by the real murderer to cover his tracks. The title is misleading, The Leopard Man is not about a man who becomes a leopard, but a man who just pretends to be one. Furthermore, the narrative reveals that the three murders are not committed by one person – against the un-written law of the genre. And on top of it all, the killer’s identity is revealed at the very beginning. But in spite of this, The Leopard Man appears to be ahead of its time: the stalking of women and their violent death is not only associated with Hitchcock and his epigone Brian de Palma, but also with the Italian cult directors Mario Bava and Dario Argento. And to go a step further, “it also anticipates Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom, in making the sight of a victim’s fear the factor that fascinates the killer and compels him to kill”. Tourneur “attributed the commercial success of his films with Lewton to war psychosis. In war time people want to be frightened.” Leopard Man has the clearest connection to war of the trio, Edmund Bansak comments that “the film is a courageous essay in the random nature of death. War time audience may not have liked The Leopard Man’s downbeat message – that the young and innocent also die, but it was an important one for them to grasp”. Fujiwara calls The Leopard Man ”a pivotal work in the careers of both Tourneur and Lewton. Pushing to extremes the experiment with narrative ambiguity undertaken in Cat People and Zombie, this radical unusual film has its own precise, inexhaustible poetry.”

THE LEOPARD MAN (1943) is seen, perhaps wrongly, as the weakest of the Lewton/Tourneur collaborations. Based on the novel by Cornel Woolrich (Rear Window), The Leopard Man is set in the nightclub milieu of New Mexico, where club owner Dennis O’Keefe (Jerry Manning) finds a leopard for his girl friend Kiki (Jean Brooks) to perform on the stage of his club. Kiki’s jealous competitor, Clo-clo (Margo), sets the leopard free and becomes one of his – presumed – three victims. Nevertheless, O’Keefe and Kiki suspect, that the leopard is only used by the real murderer to cover his tracks. The title is misleading, The Leopard Man is not about a man who becomes a leopard, but a man who just pretends to be one. Furthermore, the narrative reveals that the three murders are not committed by one person – against the un-written law of the genre. And on top of it all, the killer’s identity is revealed at the very beginning. But in spite of this, The Leopard Man appears to be ahead of its time: the stalking of women and their violent death is not only associated with Hitchcock and his epigone Brian de Palma, but also with the Italian cult directors Mario Bava and Dario Argento. And to go a step further, “it also anticipates Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom, in making the sight of a victim’s fear the factor that fascinates the killer and compels him to kill”. Tourneur “attributed the commercial success of his films with Lewton to war psychosis. In war time people want to be frightened.” Leopard Man has the clearest connection to war of the trio, Edmund Bansak comments that “the film is a courageous essay in the random nature of death. War time audience may not have liked The Leopard Man’s downbeat message – that the young and innocent also die, but it was an important one for them to grasp”. Fujiwara calls The Leopard Man ”a pivotal work in the careers of both Tourneur and Lewton. Pushing to extremes the experiment with narrative ambiguity undertaken in Cat People and Zombie, this radical unusual film has its own precise, inexhaustible poetry.”

FROM OUT OF THE PAST (1947) reunites Tourneur with producer Warren Duff, (Experiment Perilous) and DoP Nicholas Musuraka (Cat People). Based on the novel Build My Gallows High by Daniel Mainwaring, Tourneur claimed, “that he participated very closely in the writing of the script. I made big changes, with the agreement of the

FROM OUT OF THE PAST (1947) reunites Tourneur with producer Warren Duff, (Experiment Perilous) and DoP Nicholas Musuraka (Cat People). Based on the novel Build My Gallows High by Daniel Mainwaring, Tourneur claimed, “that he participated very closely in the writing of the script. I made big changes, with the agreement of the

writer, of course”. The complex and elliptic narrative is centred around Jeff Bailey (Robert Mitchum), who runs a gas station in a small town in California. In flashbacks we learn that Jeff was a New York based detective, who was asked by the professional gambler Whit Sterling (Kirk Douglas) to find his mistress Kathie (Jane Greer), who had embezzled a huge sum from him. Bailey finds Kathie in Mexico, and falls in love with her. The couple hides, but Bailey’s partner Jack Fisher (Steve Brodie) finds the couple, but is shot by Kathie, who disappears afterwards. Bailey, now owner of the gas station, is visited by a member of Sterling’s gang: Sterling has a new job for him, retrieving incriminating taxation forms from his accountant in San Francisco. Kathie is living again with Sterling, and Bailey finds soon out that he is used as the sacrificial lamb. After the murder of the accountant, Kathie shoots Sterling and escapes with Bailey – not knowing that he has phoned the police to tell them their escape route. Of the major features of Noir visual style, as identified by J.A. Place and L.S. Peterson in “Some Visual motifs of Film Noir”, Out of the Past exhibits several: low-key lighting; compositions that alternate light and dark areas; the use of objects as framing devices within the frame. All these elements are however, consistent features of Tourneur’s work outside the Noir genre. They are present to some degrees in Tourneur’s shorts and in all ten American features that Tourneur directed before Out of the Past, including the Technicolor Western Canyon Passage. Fujiwara talks about “the endlessly renewable source of cinematic fascination of Out of the Past”, even though Tourneur himself only belatedly – after the release of the film in France, when he had returned in the late 1960s to his country of birth – acknowledged it as one of his major works, calling it “along with I walked with A Zombie and Night of the Demon, his poetic manifesto.”

BERLIN EXPRESS (1948) was – regarding the topic – a one-off in Tourneur’s work, since the film is set mainly in contemporary post-war Berlin, the divided capital of Germany. Shooting in post-war Germany was like an adventure, the footage had to be sent back to Hollywood for processing. Billy Wilder had to wait for Berlin Express to finish, before starting shooting A Foreign Affair, because film equipment was a scarce commodity. The plot is, as often with Tourneur, secondary: Dr. Heinrich Bernhardt (Paul Lucas) a famous resistance fighter, is travelling from Paris to Frankfurt under an alias. During the journey, an agent, posing as Bernhardt, is killed by an explosion. In Frankfurt, Bernhardt is kidnapped by members of a Neo-Nazi movement. Four members on the train, each representing the four powers who rule Berlin, try to locate Bernhardt, after his secretary Lucienne Mirbeau (Merle Oberon) explains the situation to them. But, as it turns out the Frenchman Perrot is actually Holtzman, the leader of the Nazi underground. He is killed after another unsuccessful attempt on Bernhardt’s life. Lucien Ballard, the DoP was married to Merle Oberon, but his stylish photography does not favour his wife more than the Hollywood star. Berlin Express is actually three films in one: the first is a melodrama, where the Nazis try to kill Bernhardt. The second part is a documentary on Germany’s destruction. The third part is a typical Tourneur study of doubt, terror and impossibility.

BERLIN EXPRESS (1948) was – regarding the topic – a one-off in Tourneur’s work, since the film is set mainly in contemporary post-war Berlin, the divided capital of Germany. Shooting in post-war Germany was like an adventure, the footage had to be sent back to Hollywood for processing. Billy Wilder had to wait for Berlin Express to finish, before starting shooting A Foreign Affair, because film equipment was a scarce commodity. The plot is, as often with Tourneur, secondary: Dr. Heinrich Bernhardt (Paul Lucas) a famous resistance fighter, is travelling from Paris to Frankfurt under an alias. During the journey, an agent, posing as Bernhardt, is killed by an explosion. In Frankfurt, Bernhardt is kidnapped by members of a Neo-Nazi movement. Four members on the train, each representing the four powers who rule Berlin, try to locate Bernhardt, after his secretary Lucienne Mirbeau (Merle Oberon) explains the situation to them. But, as it turns out the Frenchman Perrot is actually Holtzman, the leader of the Nazi underground. He is killed after another unsuccessful attempt on Bernhardt’s life. Lucien Ballard, the DoP was married to Merle Oberon, but his stylish photography does not favour his wife more than the Hollywood star. Berlin Express is actually three films in one: the first is a melodrama, where the Nazis try to kill Bernhardt. The second part is a documentary on Germany’s destruction. The third part is a typical Tourneur study of doubt, terror and impossibility.

Since displacement is a central part of all Tourneur films, post-war Germany was an ideal setting. Michael Henry comments that Berlin Express “was a characteristic Tourneurian work, distilling the feeling of insecurity in which his creatures find themselves plunged as soon as they have been uprooted, placed out of their element, literally side-tracked”. But in spite of the political undertone and the ideological certainty of the protagonists, Tourneur finds ambivalence. This points towards his two 1950s films, Appointment in Honduras and The Fearmakers, both have ideological topics, but are treated with the same ambiguity and doubt as all of Tourneur’s work.

Since displacement is a central part of all Tourneur films, post-war Germany was an ideal setting. Michael Henry comments that Berlin Express “was a characteristic Tourneurian work, distilling the feeling of insecurity in which his creatures find themselves plunged as soon as they have been uprooted, placed out of their element, literally side-tracked”. But in spite of the political undertone and the ideological certainty of the protagonists, Tourneur finds ambivalence. This points towards his two 1950s films, Appointment in Honduras and The Fearmakers, both have ideological topics, but are treated with the same ambiguity and doubt as all of Tourneur’s work.

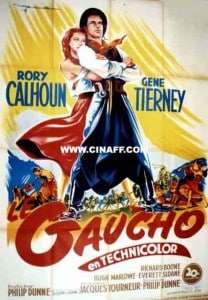

Producer/writer Philip Dunne was assigned to write the script and produce WAY OF A GAUCHO for 20th Century Fox, so that the company could recoup some of the money the Peron government had frozen in Argentina. In March 1951 Dunne informed Fox boss Darryl F. Zanuck that the proposed director, Henry King would not be available, due to his wife’s illness. Dunne goes on: “The man I want to suggest for director is Jacques Tourneur. I am absolutely delighted with the job he is doing with Anne of the Indies. In my opinion, he is a much better director than many who have made big reputations for themselves and draw down huge salaries. He is quick, sure and economical and he is getting flawless performances from his cast.”

Producer/writer Philip Dunne was assigned to write the script and produce WAY OF A GAUCHO for 20th Century Fox, so that the company could recoup some of the money the Peron government had frozen in Argentina. In March 1951 Dunne informed Fox boss Darryl F. Zanuck that the proposed director, Henry King would not be available, due to his wife’s illness. Dunne goes on: “The man I want to suggest for director is Jacques Tourneur. I am absolutely delighted with the job he is doing with Anne of the Indies. In my opinion, he is a much better director than many who have made big reputations for themselves and draw down huge salaries. He is quick, sure and economical and he is getting flawless performances from his cast.”

Zanuck agreed, and in May 1951 Tourneur arrived in Argentina. Dunne reported a month later to Zanuck: “that the Argentine government’s interest tends to become a little overwhelming. They want to have a hand in every phase of our production. Government officials were very insistent on having big stars in the picture. No reasonable government would behave in this way, but we must remember that we are dealing with incredibly stupid, provincial people”. Whilst Tourneur and Dunne were touring the country for locations, they where invariably followed by spies. Shooting under these circumstances proved difficult. There are rumours that Tourneur drank too much, but in the absence of testimony from Dunne or Tourneur, this cannot be proven. But what is true, is that Dunne and Zanuck did not employ Tourneur to add some scenes to make the central character, Martin Penalosa, more heroic. The film is set at the end of 19th century in Argentina, where Martin Penalosa is jailed for killing a man in a duel. Instead of prison he chooses the army, but does not like the harsh treatment at the hands of Major Salinas (Richard Boone). He saves Teresa Chavez (Gene Tierney), a noblewoman, from the Indians. Martin again disappears under pressure from Salinas, and leads a band of gauchos in resistance against Salinas soldiers. Martin and Teresa fall in love, and the former gives himself up to Salinas, for the sake of his wife and unborn child. It’s easy to see why this straightforward Hollywood adventure would not play to Tourneur’s strength. There is no ambivalence, white is white, and black is black. WAY OF A GAUCHO is beautifully shot, if nothing else. But it marked the decline of Tourneur in Hollywood and he would never been employed by Fox again.

THE FEARMAKERS (1958) is perhaps Tourneur’s last respectable feature before his final decline. Darwin Taylor’s novel The Fearmakers was published in 1945. Allen Eaton (Dana Andrews) returns from a Chinese POW camp after the Korean War. Eaton returns to his Washington PT office to learn that his partner Clark Baker has died under mysterious circumstances, after having sold the business to Jim McGinnis (Dick Foran). Meeting with his friend Senator Walder (Roy Gordon), Eaton is informed, that McGinnis is a suspected foreign agent (meaning he is a Communist). Eaton decides to get a job with McGinnis, and soon finds out he has forged some poll numbers for lobbyist Fred Fletcher. Eaton gains access to the poll material, and with the help of McGinnis’ secretary Lorraine (Marile Earle), proves McGinnis’ guilt. But McGinnid, with the help of his associates, attempts to kidnap and kill Eaton and Lorraine, who overpowers them and despatch McGinnis to the police. Whilst Tourneur thought, “that the film was a failure”, he certainly brings out the contradictions in the plot, featuring a McCarthy-esque Senate Committee for the defence of democracy. Eaton is a typical Tourneur hero, his vulnerability recalls the main protagonists in Nightfall and Easy Living. His recurrent headaches are the psychosomatic manifestations of his doubts. There are moments when we wonder if Eaton is fantasising part of the action. When McGinnis calls him a “brainwashed psycho”, we are again reminded of the thin ice Eaton is walking on, but the film never really challenges his worldview. Eaton is like all true Tourneur heroes – unable to leave reality, which follows him into his dreams: When the camera pans from a window across a dark room and hovers over Eaton’s bed, lit dimly with mottled shadows, we see his anguish in his haunted features. Tourneur suffused his characters with his own anxieties. AS

THE FEARMAKERS (1958) is perhaps Tourneur’s last respectable feature before his final decline. Darwin Taylor’s novel The Fearmakers was published in 1945. Allen Eaton (Dana Andrews) returns from a Chinese POW camp after the Korean War. Eaton returns to his Washington PT office to learn that his partner Clark Baker has died under mysterious circumstances, after having sold the business to Jim McGinnis (Dick Foran). Meeting with his friend Senator Walder (Roy Gordon), Eaton is informed, that McGinnis is a suspected foreign agent (meaning he is a Communist). Eaton decides to get a job with McGinnis, and soon finds out he has forged some poll numbers for lobbyist Fred Fletcher. Eaton gains access to the poll material, and with the help of McGinnis’ secretary Lorraine (Marile Earle), proves McGinnis’ guilt. But McGinnid, with the help of his associates, attempts to kidnap and kill Eaton and Lorraine, who overpowers them and despatch McGinnis to the police. Whilst Tourneur thought, “that the film was a failure”, he certainly brings out the contradictions in the plot, featuring a McCarthy-esque Senate Committee for the defence of democracy. Eaton is a typical Tourneur hero, his vulnerability recalls the main protagonists in Nightfall and Easy Living. His recurrent headaches are the psychosomatic manifestations of his doubts. There are moments when we wonder if Eaton is fantasising part of the action. When McGinnis calls him a “brainwashed psycho”, we are again reminded of the thin ice Eaton is walking on, but the film never really challenges his worldview. Eaton is like all true Tourneur heroes – unable to leave reality, which follows him into his dreams: When the camera pans from a window across a dark room and hovers over Eaton’s bed, lit dimly with mottled shadows, we see his anguish in his haunted features. Tourneur suffused his characters with his own anxieties. AS

JACQUES TOURNEUR RETRO | LOCARNO FILM FESTIVAL 2-10 AUGUST ’17