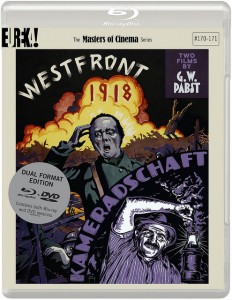

WESTFRONT 1918 (VIER VON DER INFANTRIE)

WESTFRONT 1918 (VIER VON DER INFANTRIE)

Dir.: Georg Wilhelm Pabst: Cast: Gustav Dießl, Fritz Kampers, Hans-Joachim Moebis, Jackie Mounier; Germany 1930, 75 min.

KAMERADESHIP (KAMERADSCHAFT)

Dir.: George Wilhelm Pabst; Cast: Fritz Kampers, Alexander Granach, Ernst Busch, Elisabeth Wendt; Deutschland 1931, 93 min.

Austrian director Georg Wilhelm Pabst (1885-1967) was at the time of the transition between silent and sound film perhaps the leading European filmmaker: from 1925 (The Joyless Street) to 1931 (Comradeship), his silent classics included Pandoras’s Box and Diary of a Lost Girl, followed by Westfront 1918 and The 3 Penny Opera, where he introduced sound in a very imaginative way.

It seems nearly incomprehensible then that the rest of his output of 23 films – shot between 1932 and 1956 – gwould merit only a comment regarding the waste of this great talent. He went to France in 1932 to direct Don Quixote, had a disappointing time in Hollywood with A modern Hero (1934), before settling again in France until the outbreak of WWII, when he returned to Austria – by now part of the Third Reich – where he directed three mediocre films, before producing the worst of the “light entertainment” in post-war Austria and West Germany. Just “The Trial” (1946) can be seen as an apology for having worked for the Goebbels controlled film industry which, after all, forbid any showing of Westfront 1918 when the Nazis came to power in 1933.

Kracauer is only too ready to concede “that Pabst took the lead in films of the pre-Hitler period, which overtly indulged in social criticism and belonged among the top-ranking artistic achievements of the time. Aesthetic quality and leftist sympathies seemed to coincide”. But he followed with an important caveat: “His [Pabst’s] pre-occupation with social problems outweighed the melodramatic characteristics of his ‘New Objectivity period”. Based on a novel by Ernst Johannsen, WESTFRONT shows war as inhuman on all levels: the anti-hero Karl (Dießl) literally goes mad under the pressure. His friend, a young student-soldier (Moebis) spends the first (and only night) with a French woman, but volunteers to serve for a particularly dangerous part of the Front. Here he meets Karl, who has just returned from a vacation at home experiencing food shortages in all the shops. He has also surprised his wife with the son of the local butcher – selling herself for extra-meat rations. When Karl re-joins his comrades on the front, he learns that the student has been killed by a French soldier who himself now lies wounded in no-mans land, screaming for help. Karl, suicidal, takes part in a relief operation, where a German lieutenant goes mad, shouting “Hurrah, hurrah”, whilst Carl, wounded, also loses his mind. He is transported to a hospital where he dies in a delirium, images of his wife dominating his final moments.

Whilst Kracauer might have a point in claiming that “ WESTFRONT 1918 is an outright pacifist document going, as such, beyond the scope of New Objectivity, its fundamental weakness consists in not transgressing the limits of pacifism itself. The film tends to demonstrate that war is intrinsically monstrous and senseless, but this indictment is not supported by the slightest hint of causes”. This may be so, but the Nazis seemed to have got the message. Undeterred, Pabst went on fighting against the rise of the Nazis, he even became president of Dacho, the top organisation of German film workers, succeeding the late Lupo Pick.

KAMERADSCHAFT, is based on an idea by Karl Otten that follows a real event which happened before WWI in the Courriers, near the French/German border, where German miners were helping in the rescue of their French counterparts. Pabst sets the narrative after the signing of the Versailles treaty. Unemployment in Germany was rising, and many miners were trying to cross the border to work in French mines, which upset the local population. In a scene at the beginning, a young French woman declines to dance with a German miner, making her feelings very clear. Nevertheless, when the news of the explosion in the French mine reaches Germany, the miners spontaneously cross the border assist in the rescue operation. A contemporary critic commented: “Nothing seems staged in the episodes of the rescue operation. The mine had been rebuilt in the studio, and DoP Fritz Arno Wagner (who was also co-DoP in Westfront), re-created a claustrophobic world. Kracauer saw progress since his criticism of WESTFRONT: “Pabst’s mining film progresses his theoretical thought: for he now tries to make his pacifist leanings invulnerable by endorsing the socialist doctrine. Comradeship advocates the international solidarity of the workers, characterising them as the pioneers of a society where national egoism, the eternal source of wars, is abolished. It is the German miners, not their superiors, who conceive the idea of the rescue action. But whist Kracauer lauds Pabst for showing that “the passages dealing with the management of the French and German mines subtly imply the alliance between capitalists and nationalists” he follows that with the comment: “even though the socialist pacifism of Comradeship was better founded than the humanitarian pacifism of WESTFRONT, it does not justify the assumption that it was more substantial. Pabst penetrates reality visually, but leaves its intellectual core shrouded”. It should be said, that the huge majority of reviewers disagreed with Kracauer – but COMRADESHIP was not a success at the box-office.

The real question still remains: What really happened to Pabst after COMRADESHIP his most substantial film. We know that he settled in France to direct and supervise bland and unconvincing melodrama, returned to Nazi Germany in 1939 and served “Papas Kino” (Dad’s Cinema) in Germany after 1946 – but the data alone does not explain where his talent went. AS

OUT ON BLURAY/DVD COURTESY OF MASTERS OF CINEMA EUREKA 24 JULY 2017