In our occasional series on neglected filmmakers, Richard Chatten looks at the world of Mario Zampi (1903-1963)

There is a scene in Mario Zampi’s Laughter in Paradise (1951) in which Alistair Sim – who for plot purposes needs to spend a month in jail – attempts to get himself arrested by ostentatiously pocketing a necklace in a store; only to have it swiftly lifted by a pickpocket before the store detective has time to apprehend him. A characteristically adroit summing up by Zampi and his screenwriters Jack Davies & Michael Pertwee (son of the playwright Roland Pertwee and elder brother of Jon) of the low-level criminality then rife in postwar austerity Britain; whose move into affluence they lovingly charted in a series of genially satirical popular comedies with which Zampi’s name became synonymous before his relatively early death in 1963 at the age of 60.

Described by his obituarist in Variety as a “mercurial little man” (Peter Sellers modelled the effusive Italian film director he played in After the Fox on Zampi), Mario Zampi (seen left with Sellers) was born in Sora in Italy on 1 November 1903, entered films as an actor at the age of 17, and had already worked in Italian films in various capacities before moving to Britain with the collapse of the Italian film industry in 1922. By the 1930s he was an editor for Warner Brothers at their Teddington studios, and in 1937 with his compatriot Filippo Del Giudice co-founded the production company Two Cities. The first film he directed was Thirteen Men and a Gun (1938), a First World War drama set on the Austro-Hungarian front starring Arthur Wontner, shot in Italy in both English and Italian versions. His next feature, Spy for a Day (1940), was a vehicle for the North Country comedian Duggie Wakefield also set during the First World War, co-scripted by Emeric Pressburger (who may have been responsible for the touching sequence depicting a mute attempt at communication between Wakefield and a German corporal played by George Hayes). Zampi also produced Two Cities’ first big success – French Without Tears – in 1939; but at this point suffered an ironic setback by himself being interned as an enemy alien for the next four years.

Described by his obituarist in Variety as a “mercurial little man” (Peter Sellers modelled the effusive Italian film director he played in After the Fox on Zampi), Mario Zampi (seen left with Sellers) was born in Sora in Italy on 1 November 1903, entered films as an actor at the age of 17, and had already worked in Italian films in various capacities before moving to Britain with the collapse of the Italian film industry in 1922. By the 1930s he was an editor for Warner Brothers at their Teddington studios, and in 1937 with his compatriot Filippo Del Giudice co-founded the production company Two Cities. The first film he directed was Thirteen Men and a Gun (1938), a First World War drama set on the Austro-Hungarian front starring Arthur Wontner, shot in Italy in both English and Italian versions. His next feature, Spy for a Day (1940), was a vehicle for the North Country comedian Duggie Wakefield also set during the First World War, co-scripted by Emeric Pressburger (who may have been responsible for the touching sequence depicting a mute attempt at communication between Wakefield and a German corporal played by George Hayes). Zampi also produced Two Cities’ first big success – French Without Tears – in 1939; but at this point suffered an ironic setback by himself being interned as an enemy alien for the next four years.

Having spent most of Two Cities’ wartime glory years cooling his heels in Canada, he laboriously worked his way back into the business directing three very low budget mystery films: The Phantom Shot (1947), The Fatal Night (1948) and Shadow of the Past (1950), none of which appear to have been seen since they were originally released. But The Fatal Night caused a sensation at the time and those who saw it then still vividly recall how much it scared them as youngsters. Recounting the fate of a man who accepts a bet to spend a night in a haunted house, and with a memorable sting in the tail, it was scary enough to carry an ‘H’ certificate, was described by David Quinlan as “one of the most frightening films ever made, full of horrors not quite or only half-seen”, and reveals a side to Zampi otherwise wholly unsuspected. (The BFI hold material from the film, so we may yet hope to see it resurrected in our lifetimes).

Having spent most of Two Cities’ wartime glory years cooling his heels in Canada, he laboriously worked his way back into the business directing three very low budget mystery films: The Phantom Shot (1947), The Fatal Night (1948) and Shadow of the Past (1950), none of which appear to have been seen since they were originally released. But The Fatal Night caused a sensation at the time and those who saw it then still vividly recall how much it scared them as youngsters. Recounting the fate of a man who accepts a bet to spend a night in a haunted house, and with a memorable sting in the tail, it was scary enough to carry an ‘H’ certificate, was described by David Quinlan as “one of the most frightening films ever made, full of horrors not quite or only half-seen”, and reveals a side to Zampi otherwise wholly unsuspected. (The BFI hold material from the film, so we may yet hope to see it resurrected in our lifetimes).

After changing tack with a revue film starring Max Wall, Come Dance with Me (1950) (whose acts included Stanley Black and his orchestra, who also scored this and most of his subsequent films), there then came the film that would define the remainder of Zampi’s career as a producer-director. An episodic comedy about four beneficiaries of a notorious practical joker’s will – each obliged to do something extremely humiliating and unpleasant to inherit £50,000 – Laughter in Paradise was the highest-grossing British film of 1951 and Zampi never looked back. Despite his wartime incarceration, Zampi seems to have felt little ill-will towards his adopted homeland – although maybe it gives a slight edge to his gentle mockery of the British character – and he certainly did an exemplary job of capturing our sense of humour in the films that followed. Having taken a shine to George Cole, Zampi commissioned his next screenplay from Davies and Pertwee especifically for him – a Cold War farce called Top Secret (1952) about a sanitary engineer visiting Moscow mistaken for an atomic scientist. Now hitting his stride, on the set of Top Secret Zampi happily acknowledged that he saw his films as collaborative endeavours (including his son Guilio (1923-2003), first as an editor, then as associate producer): “I am standing talking to you now but the work still goes on”, he declared. “My team are worrying more about the picture than I am.”

After changing tack with a revue film starring Max Wall, Come Dance with Me (1950) (whose acts included Stanley Black and his orchestra, who also scored this and most of his subsequent films), there then came the film that would define the remainder of Zampi’s career as a producer-director. An episodic comedy about four beneficiaries of a notorious practical joker’s will – each obliged to do something extremely humiliating and unpleasant to inherit £50,000 – Laughter in Paradise was the highest-grossing British film of 1951 and Zampi never looked back. Despite his wartime incarceration, Zampi seems to have felt little ill-will towards his adopted homeland – although maybe it gives a slight edge to his gentle mockery of the British character – and he certainly did an exemplary job of capturing our sense of humour in the films that followed. Having taken a shine to George Cole, Zampi commissioned his next screenplay from Davies and Pertwee especifically for him – a Cold War farce called Top Secret (1952) about a sanitary engineer visiting Moscow mistaken for an atomic scientist. Now hitting his stride, on the set of Top Secret Zampi happily acknowledged that he saw his films as collaborative endeavours (including his son Guilio (1923-2003), first as an editor, then as associate producer): “I am standing talking to you now but the work still goes on”, he declared. “My team are worrying more about the picture than I am.”

After a return to Italy to make another light-hearted take on the Cold War, Ho scelto l’amore (1953) – starring Renato Rascel as a junior Russian official accidentally separated from his delegation in Venice – Zampi made the first of his two films in Technicolor, Happy Ever After (1954), a riotous piece of rollicking Irish blarney in which an entire village draws lots to set in motion a series of comically failed attempts to murder an obnoxious new landlord played by David Niven. Also in Technicolor was Now and Forever (1956), adapted by Pertwee and R.F.Delderfield from the latter’s play The Orchard Walls; showcasing Janette Scott’s first adult role as a schoolgirl who elopes to Gretna Green. Ravishingly photographed by Erwin Hiller, it was described by William Everson in Love in the Film (1979) as “a paean of praise to the English countryside, its background of springtime was essential to the story of exuberant young love” of “warm and real humor…Many of the compositions are designed purely to stress beauty, color and youth…Even in 1956, Now and Forever was a complete anachronism, something like a Deanna Durbin musical romance without the music.”

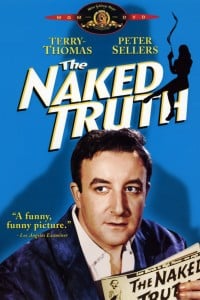

But if anyone thought Zampi was mellowing, the two black & white farces he made next starring Terry-Thomas were to prove vintage Zampi. The Naked Truth (1957) – described by Raymond Durgnat as “the first British film to lift its upper lip and show a satirical fang” – took it’s lead from the salacious magazine Confidential, whose squalid revelations about Hollywood celebrities amounted to a virtual reign of terror during the mid-fifties (and had already been the subject of a Hollywood drama called Slander). As in Happy Ever After, a group of individuals are driven out of desperation to commit murder; in this case a selection of the great and the good threatened with the revelation of their feet of clay by the editor (played by Dennis Price) of a scandal magazine called The Naked Truth. The most spinechilling of these is Peter Sellars as Wee Sonny MacGregor a TV personality, master of disguise and slum landlord decribed by Durgnat as “a loveable homey quiz master really devoured by contempt for the doddering old folk to whom he awards his prizes”.

But if anyone thought Zampi was mellowing, the two black & white farces he made next starring Terry-Thomas were to prove vintage Zampi. The Naked Truth (1957) – described by Raymond Durgnat as “the first British film to lift its upper lip and show a satirical fang” – took it’s lead from the salacious magazine Confidential, whose squalid revelations about Hollywood celebrities amounted to a virtual reign of terror during the mid-fifties (and had already been the subject of a Hollywood drama called Slander). As in Happy Ever After, a group of individuals are driven out of desperation to commit murder; in this case a selection of the great and the good threatened with the revelation of their feet of clay by the editor (played by Dennis Price) of a scandal magazine called The Naked Truth. The most spinechilling of these is Peter Sellars as Wee Sonny MacGregor a TV personality, master of disguise and slum landlord decribed by Durgnat as “a loveable homey quiz master really devoured by contempt for the doddering old folk to whom he awards his prizes”.

Too Many Crooks (1959) was to prove the last truly vintage Zampi (based on an idea by Jean Nery & Christiane Rochefort), and prompted Films and Filming’s editor Peter G. Baker to declare “thank goodness the Rank Organisation is associated in distributing a subject in such dubious taste”. The premise of a gang of bungling crooks abducting Terry-Thomas’s wife (and both the gang and the wife’s mortification when he tells them he isn’t interested in paying the ransom) was recycled at least twice by Hollywood over the next thirty years – as The Happening with Anthony Quinn and Ruthless People with Bette Midler – just as the final section in which the gang disguise themselves as undertakers strongly anticipates Joe Orton’s Loot. The climax too of Zampi’s next film, Bottoms Up! (1960) – based on the TV series Whacko! – in which the pupils of Chiselbury School stage an armed uprising against their drunken, corrupt headmaster (Jimmy Edwards) and his ineffectual staff even more strongly antipates Lindsay Anderson’s lf…. (although it’s possible that the makers of both films were taking their lead from Jean Vigo’s Zero de Conduite).

Zampi’s final film was a little-seen Italian-British co-production, Five Golden Hours (1961), filmed on location in Bolzano in Italy in both English and Italian-language versions with a largely British supporting cast. The teaming of Zampi and the sardonic American comedian Ernie Kovacs as a conman certainly sounds promising; but maybe it needed Michael Pertwee to give the script more bite. Kovacs himself, however, said that this was his personal favourite of his own films.

Zampi died in the Italian Hospital, London on 2 December 1963, and it’s hard to say what direction his career might have taken in the volatile climate of the British cinema of the 1960s. But the unsavoury revelations during the Profumo scandal that summer – especially about the thuggish slum landlord Peter Rachman – showed The Naked Truth to have been remarkably prescient; and his films remained popular on TV for another twenty years in those far off days when it was still possible to see black & white films at peak viewing time. RICHARD CHATTEN