Director: Fenton Bailey, Randy Barbato

Documentary with Debbie Harry, Fran Lebowitz, Brook Shields; USA 2016, 118 min.

Directors Fenton Bailey and Randy Barbato (Party Monster, Becoming Chaz) have used an angry comment by Senator Jesse Helms (R) for the title of their portrait of photographer Robert Mapplethorpe (1946-1989): whose death from the complications of HIV, caused Helms to make the controversial complaint, on the House floor, over public money spent on an exhibition of the the photographer’s work, asking people “to look at the pictures’, and calling the dead artist a “jerk”.

Robert Mapplethorpe grew up in the sleepy borough of Queens, New York. He had five siblings, all of them were brought up as Catholics and he showed early promise with his drawings, one of his first was of the Virgin Mary drawn in the style of Picasso. As with Bunuel, this Catholic upbringing would shape Mapplethorpe’s work: his photos of tortured lovers were very much the equivalent of those depicting Catholic martyrs – he simply transferred these icons into his personal world.

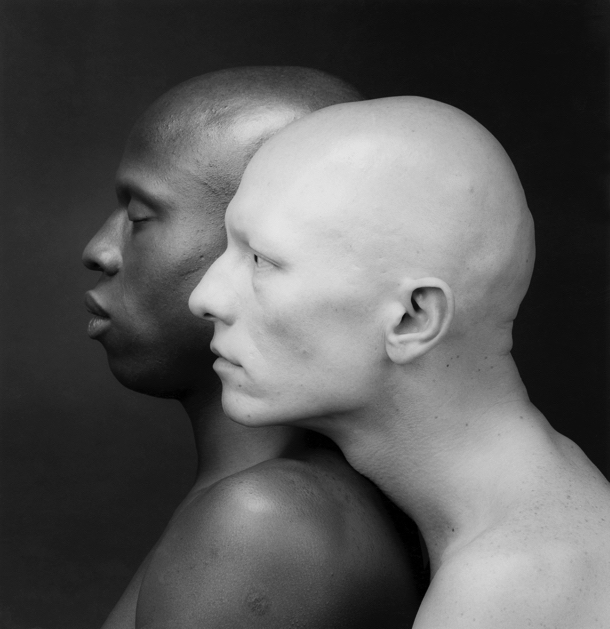

After studying Graphic Art at the Pratt Institute, this well-crafted documentary shows how he found his way into photography, at first with the help of Polaroid cameras. At this time in the late Sixties, photography was seen more as a craft than an art form. His first love was the singer Patti Smith, they moved into the famous Chelsea Hotel during their relationship, which lasted between 1967 and 1972; the couple stayed in contact, even after it became clear that Robert was homosexual. Robert then fell for art curator Sam Wagstaff (1921-1987) at a party in 1972, in a love affair that was to last15 years. Wagstaff was Mapplethorpe’s mentor and benefactor, buying a loft in 35 West 23 Street for his lover in 1980 – then worth half a million dollars. The pair were active in the burgeoning BDSM scene in New York. Robert, whose charm was enormous, admitted that his relationship with Wagstaff was only possible because of the curator’s wealth; Mapplethorpe also courted other influential figures, such as the editor of Drummer Magazine, Jack Fritscher. In the last ten years of his life, Mapplethorpe developed a yen for relationships with black men.

“The pictures” – of naked men engaged in sexual acts, or Mapplethorpe’s self portraits with a whip or with horns – Senator Helms was complaining about, are very much in the minority: surprisingly, his floral photographs are much more numerous. But even his most sensationalist work is anything but pornographic: everything is stylised perfection. Mapplethorpe was a master of details, Robert saw himself “as being a sculptor without having to spend all the time modelling with my hands”.

Bailey and Barbato are a little harsh on their subject: it is true that Robert was after fame and money – but this goes for most ambitious people, not only artists. And yes, his sibling rivalry with his brother Edward, also a photographer, perhaps went too far – Robert insisting that Edward should use a pseudonym for his work – but the long interviews with the Edward take up too much time. That said, the directors (and the images of DOPs Mario Panagiotopoulos and Huy Truong) give Robert Mapplethorpe the credit he deserved: he created new ways of seeing and aesthetics, to change the image of photography in his very personal way. AS

ON RELEASE AT SELECTED ARTHOUSE CINEMAS FROM 22 APRIL 2016