Andre Simonoveisz looks back at the life and work of New Wave director JACQUES RIVETTE (1928-2016).

Jacques Rivette was born in Rouen, where he shot his first short film Aux Quatre Coins in 1948, inspired by the work of Jean Cocteau. The following year he moved to Paris, submitting his film to the prestigious IDHEC Film School where he was rejected. Undeterred, he took courses at the Sorbonne and soon became an habitué at the Cinemathèque Française, run at the time by Henri Langlois. Meeting up with the other members of what would become the “Band of Five” – all film critics at “Cahiers du Cinéma”, who would later form the Nouvelle Vague movement as directors: Jean-Luc Godard, Eric Rohmer, François Truffaut and Claude Chabrol.

Rivette was the political exception with his left-wing leanings, the rest, particularly Godard, were very much to the right. Nevertheless, Rivette was the leading theoretician of the group and when he took over the editorship of Cahiers from Rohmer in 1963, he opened up the magazine to luminaries outside the film word, namely Roland Barthes and Pierre Boulez.

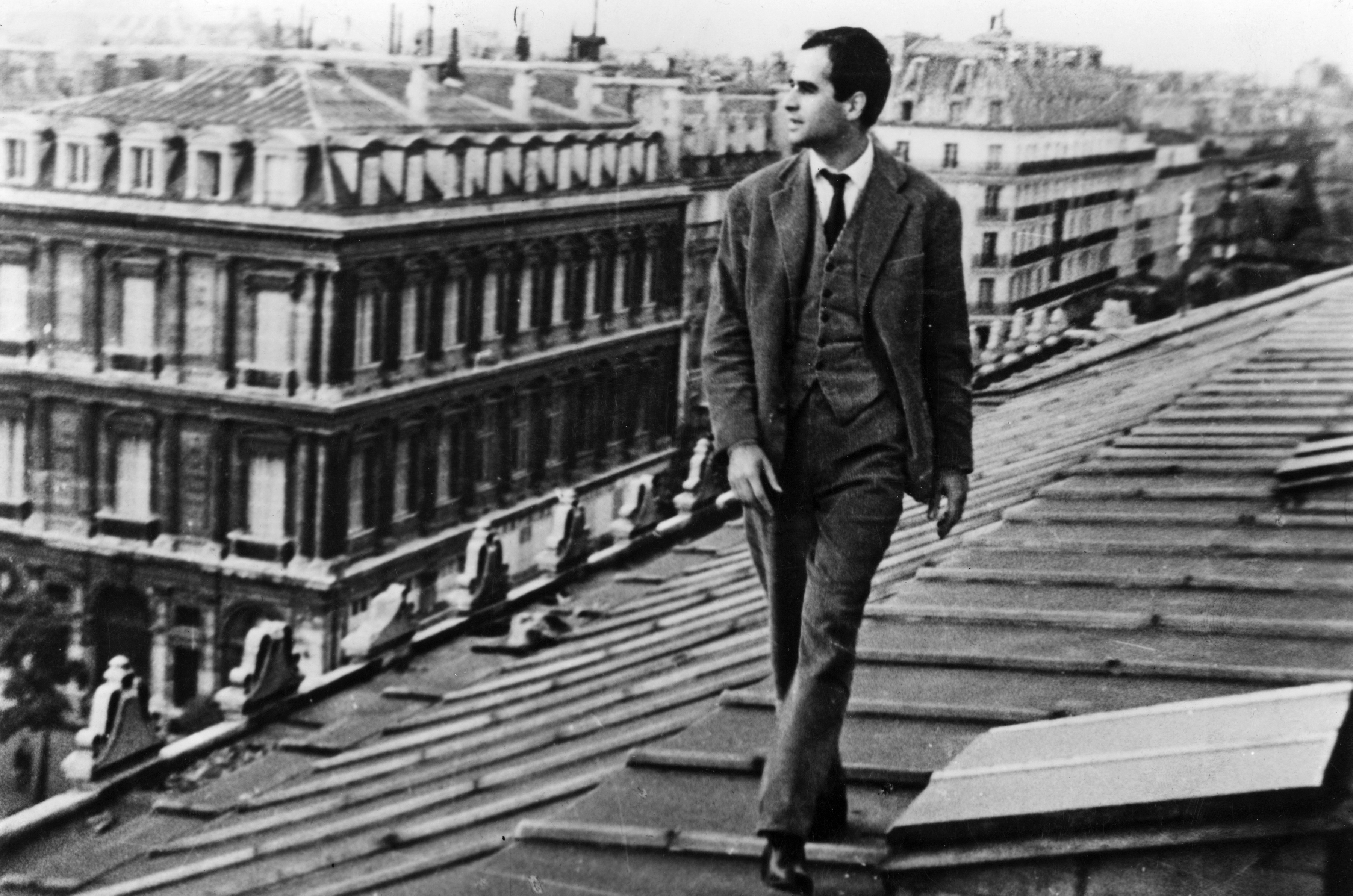

In 1950 Rivette directed his second short film Le Quadrille, produced by Godard who also played the lead. Four years later, Rivette and Truffaut began a series of interviews with film directors they admired, among them Hitchcock, Hawks, Fritz Lang and Orson Welles. In 1952 Rivette filmed his third short Le Divertissement, followed by Le Coup du Berger (1956), scripted by Chabrol. With borrowed money and short film reel ends, Rivette begun to shoot his first feature film Paris Nous Appartient in 1958. Running out of money, the film was only finished and premiered in December 1961, long after Godard and Chabrol had started the movement with their first films.

Paris Nous Appartient has all the hallmarks of the later Rivette films: mysteries, theatre productions (in this case Shakespeare’s Pericles) and old houses. But Rivette’s films are not simply mysteries, but studies of the phenomenon of mysteries. In this way, Rivette produced narratives about narratives; about the process and working of fiction itself. All this relates to Rivette’s closeness to anothor movement of the time, the “Noveau Roman” along with Robbe-Grillet and Marguerite Duras. It took him until 1966 to make his next film, Suzanne Simonin, la Religieuse de Diderot, which starred Anna Karina. The government tried to ban the film but it eventually became Rivette’s only hit at the box office. But Rivette was deeply rustrated with the conventional way he worked, particularly his script writing, which bored him.

With Amour Fou (1968) he started to improvise whilst shooting, culminating in his most important work, Out 1 : Noli me tangere, (left) an experimental film which runs for nearly 13 hours and was shown in Le Havre in 1971 as a “work in progress”. Since then it has been rarely shown, until the recent DVD/Blu-ray release by Arrow Films and Video. The audience of Out 1 were reluctant to let go of the film, and like many serials, they wanted the film to continue indefinitely. Emotionally, they had bought into the story and identified with its characters. This interesting development implies that the real community of Out 1 is the community of the film itself, not only formulated by the cast and crew, but also by the viewers: who (unwittingly) were witnessing a process of strong identification, built up over the 13 hour viewing. Out 1 was the first film the audience “wanted to live in”: it appeared that he actors had forgotten that they were acting and Rivette realised crucially that “men want to solve a conflict by denial, women through dialogue”.

With Amour Fou (1968) he started to improvise whilst shooting, culminating in his most important work, Out 1 : Noli me tangere, (left) an experimental film which runs for nearly 13 hours and was shown in Le Havre in 1971 as a “work in progress”. Since then it has been rarely shown, until the recent DVD/Blu-ray release by Arrow Films and Video. The audience of Out 1 were reluctant to let go of the film, and like many serials, they wanted the film to continue indefinitely. Emotionally, they had bought into the story and identified with its characters. This interesting development implies that the real community of Out 1 is the community of the film itself, not only formulated by the cast and crew, but also by the viewers: who (unwittingly) were witnessing a process of strong identification, built up over the 13 hour viewing. Out 1 was the first film the audience “wanted to live in”: it appeared that he actors had forgotten that they were acting and Rivette realised crucially that “men want to solve a conflict by denial, women through dialogue”.

Women, particularly, dominate nearly all Rivette’s films. Regular collaborator Bulle Ogier once said about Rivette’s work: “The actor works out her role according to the scheme: an exercise in improvisation to the edge of despair. It’s then up to Rivette to put the jigsaw together in the montage”. And Juliet Berto, also a regular of Rivette’s films, concludes: “Rivette’s main directing work was done at home during the editing stage: that’s where he organises the disorderly action of the puppets”.

Céline et Julie vont en Bâteau (1974) is perhaps the ultimate Rivette film. To start with, the title could mean in translation ‘Celine and Julie are taken for a ride’ or ‘Celine and Julie are falling into fiction’. The leading duo, who could be lovers, sisters or simply friends, enjoy a life of games, storytelling and magic tricks. One day, Celine (Dominique Labourier) tells Julie (Juliet Berto) about the house of the Levinson family (which she dreamed about), where the two young women become maids, to save the life of Madlyn (the daughter of widower Olivier) from the murderous intents of Camille, his sister in-law, and Sophie, both of whom want to marry Olivier. But Olivier can’t marry as long as Madlyn is alive so the women want to kill the child. The Levinson house is like most of Rivette’s houses: large, rambling and mysterious. Analytically speaking, the house is the geographical centre of the psyche, the spatial organisation of our first remembered world; and first and foremost shelter; a place of security and a more complex version of the maternal womb, were we can dream in peace. These are common factors of Rivette ‘houses’, and in all cases the protagonists are women, whilst the house belongs, or is at least inhabited by a man. Life the city of Paris, the bourgeois houses become the ‘theatres’ for Rivette’s mobile performances. In La Bande des Quatre (1988), four young actresses from the Paris banlieu try to solve the mystery of a house’s owner.

Wining the Grand Prix in Cannes in 1991 with La Belle Noiseuse was certainly a high point for Rivette, together with his two films about Jeane d’Arc. The first was Jeanne la Pucelle, which starred Sandrine Bonnaire as a very earthy version of the saint. With the second (also starring Bonnaire, Secret Defense(1998), Rivette came full circle with his love for Hitchcock as a critic. It is a loose rebuilding of the Electra myth; and, like Hitchock in Vertigo, Rivette reinforces in this his most important neo-noir film, the theme of the double through the use of a shadow: When Ludivine (Laure Marsac) enters the office of Walser (the man who murdered her father), harsh light casts a full shadow of Ludivine’s body on the wall between her and Walser (Jerzy Radziwilowicz), as a violent reminder of her murdered sister.

Games are the main standard bearers for for Rivette’s narratives: from the Coup du Berger onwards, ‘play’ and ‘games’ are, among other things, the vehicle for this tension in his narratives; for a desire for structure; a sense and context and a contradictory imposition that remains open to experiment, chance and unpredictability.

These magical games, indulged by the double protagonists of Celine et Julie, or in Noroît (1976) or Duelle (1976), are a sign of refusing maturity. The inability to grow up and to stay in a world of magic and mystery; but also a trap in which the child-goddess can only repeat the same confrontation with herself/other, or face mutual destruction. Which brings us to the conclusion of Rivette’s oeuvre: His films are created in the spirit of a kindergarten group performing an end-of-year show for the grown-ups, but also the other way round.

Rejecting the ‘auteur’ theory and calling it a myth, Jacques Rivette fell neither into the trap of self-centred Jean-Luc Godard, who needs to keep re-inventing himself; nor did he succumb, like Truffaut and Chabrol, to the banalities of commercial cinema. Ultimately he was the playful grown-up child of his own films; always conscious that “when curiosity disappears, there is nothing left but to lie down and wait for our last breath”. AS

THE JACQUES RIVETTE COLLECTION IS NOW OUT ON DVD BLU-RAY COURTESY OF ARROW FILMS AND VIDEO | CELINE ET JULIE IS ALSO CELEBRATING A BLURAY RELEASE ON 20 NOVEMBER 2017 COURTESY OF BFI FILMS