Perfectly situated in the hub of Europe’s Financial centre, The Barbican offers a selection of films and discussions this Autumn exploring money through themes of power, wealth, poverty, corruption and consumerism.

Perfectly situated in the hub of Europe’s Financial centre, The Barbican offers a selection of films and discussions this Autumn exploring money through themes of power, wealth, poverty, corruption and consumerism.

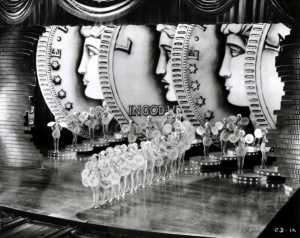

From the silent era comes Erich von Stroheim’s potent thriller GREED, shows how the corruptive force of a sudden fortune ruins the lives of three Californians. The glitzy side of Hollywood is depicted in Mervyn LeRoy’s comedy musical GOLD DIGGERS OF 1933 (right) where millionaire turned composer Dick Powell uses his fortune for the good of the community. Robert Bresson won best director at Cannes 1983 for his classic l’ARGENT based on Tolstoy’s The Forged Coupon that explores the journey of 500 franc note and the devastating effect on its final recipient. In THE WHITE BALLOON (1995), Jafar Panahi’s slice of realism, written by Abbas Kiarostami examines how a child is swindled out of her birthday money and blockbuster THE WOLF OF WALL STREET charts the rise to riches and ultimate fall of New York stockbroker Jordan Belfort (Leonardo DiCaprio) due to a 1990s securities scam. In AMERICAN PYSCHO (2000) Christian Bale stars as another wealthy City who sociopathic personality enables him to fund a lifestyle and escape into his own American dream. These are our recommendations:

GREED | Dir: Erich von Stroheim; Cast: Gibson Gowland, Za Su Pitts, Jean Hersholt | USA 1923; 462 min. (original), 140 min. (theatrical release), 239 min. (restored version)

GREED | Dir: Erich von Stroheim; Cast: Gibson Gowland, Za Su Pitts, Jean Hersholt | USA 1923; 462 min. (original), 140 min. (theatrical release), 239 min. (restored version)

Roger Ebert called Greed “the ‘Venus of Milo’ of films, acclaimed as a classic, despite missing several parts deemed essential by its creator”. It is also a classic example of Hollywood butchery, in this case performed by the new partners of MGM, Irving Thalberg and Louis B. Mayer; Thalberg turning out to be Von Stroheim’s bête noir having already fired him from Merry-Go-Round at Universal. Just twelve people saw the original version (edited from 85 hours of total footage); one of them, the director Rex Ingram, believed that Greed was the best film ever and would never be surpassed. Shot over 198 days from June to October 1923 in San Francisco, Death Valley and Placer Country, California, it took over a year to edit, and cost $ 564 654 (around $ 60 million in todays money), but only grossed $ 274827 at the box office.

Based on the novel ‘Mc Teague’ by Frank Norris, Greed centres around the relationship of John Mc Teague (Gibson) and his wife Trina (Pitts). Mc Teague is operating as a dentist without a licence, when he meets Trina, who has been the girl friend of his best friend Marcus Schouler (Hersholt). After Trina wins $5000 in the lottery just before she marries McTeague, Schouler wants her back, and denounces Mc Teague to the police, for working without a licence. Mc Teague asks Trina for $3000, to save his skin, but she refuses him, being too fond of the money – she cleans the coins until they glitter. Mc Teague murders his wife and Schouler again reports him to the police. Mc Teague flees to Death Valley from his pursuers, among them Schouler, whom he fights to the death.

Greed caused violence to break out off screen too. The film was nearly destroyed because of its unwieldy length, making it almost impossible to edit. A fist fight broke out between Mayer and Von Stroheim, after the former provoked the director with “I suppose you consider me rabble”, to which Von Stroheim answered “Not even that”. Mayer struck him so hard, that he fell through the office door. Mayer wanted a uplifting film for the “Jazz Age’, and Greed was uncompromising realism. But the studio even changed the meaning of what was left with inter-title cards. In the MGM version, when Trina and Mc Teague went by train to the countryside, the MGM title card reads “This is the first day it hasn’t rained in weeks. I thought it would be nice to go for a walk”. In Rick Schmidlin’s reconstructed version of 1999 (based on Stroheim’s 330 page shooting script and stills) it reads: “Let’s go and sit on the sewer” – and so they sit down on the sewer.

Von Stroheim, who invented an aristocratic upbringing and a glorious army career for himself, was nevertheless a master of realism when it came to films: when Gowland and Hersholt fight in Death Valley, the temperature was over 120 degrees, and many of the cast and crew had to take sick leave, Von Stroheim coaxed the actor on “Fight, fight. Try to hate each other as you hate me”. AS

L’ARGENT (1983) | Dir.: Robert Bresson | Cast: Christian Patey, Caroline Lang, Sylvie Van der Elsen, Michel Briguet France/Switzerland 1983, 85 min.

L’ARGENT (1983) | Dir.: Robert Bresson | Cast: Christian Patey, Caroline Lang, Sylvie Van der Elsen, Michel Briguet France/Switzerland 1983, 85 min.

To find the money to direct what turned out to be his last film L’Argent, Robert Bresson needed the intervention of the French Minister of Culture, Jack Lang – just like he did with L’Argent’s predecessor Le Diable Probablement (1977). L’Argent went on to win the Director’s Prize in Cannes, sharing in with Andrei Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia.

L’Argent is Bresson’s truest ‘Dostoevskyan’ work, even though it is based on Leo Tolstoy’s novella ‘The Forged Coupon’. From the outset, money changes hands at a furious tempo: a young boy asks his father for pocket money but what he gets is not enough for him; he pawns his watch to his friend, who gives him a forged 500 Franc note. The boy, having recognised the forgery, takes the money to a photo shop, buying only a cheap frame with the note. The manager of the shop – after discovering the forged note, scolds his wife for being so naïve. But she reminds him that he took in himself two forged notes of the same denomination the week ago. The owner gives all three notes to Yvon Targe (Patey), who is the gas bill collector. Later, in a restaurant, Yvon tries to use the money but the waiter recognises the forgeries. Yvon is spared jail, but loses his job. Moneyless, he acts as get-away-driver for a friend’s robbery, but the plot fails and Yvon’s run of bad luck continues until its devastating denouement.

Apart from opening, everything is told in Bresson’s very own elliptical but terse style, making the smallest detail more important than the action. The prison is shown as a labyrinth in which Yvon is lost, particularly when sent into solitary confinement after a fight with fellow prisoners. The prison is shown in great detail in a similar vein to Un Condamne à mort s’est Echappé (1956) and becomes the material witness to Yvon’s suffering. The murder of the hotel-keepers is shown only in hindsight: a long medium shot of bloody water in a basin, followed by a close-up of Yvon emptying the till. The failed robbery is shown by the reactions of the passersb-by, who witness Yvon driving off, after shots are fired. Finally, enigma of the last shot in the restaurant, when the crowd looses interest in Yvon, as if he were simply not enough of a person, in spite of the hideous murders. In this shot, the whole universe of Bresson is captured: there seems to be no sense in human deeds, and, therefore there is no question of a why, and no guilt, but, perhaps just redemption.

DOP Pasqualino de Santis (Death in Venice) excels particularly in bringing together the close-up shots of the objects, and the long shots of Yvon as he gets increasingly lost: in the robbery, in prison, and in the cosy house of an old woman. We feel him shrinking, as he loses his identity during the film, becoming a total non-person by the end. The acting is as understated as possible, and Bresson closes his oeuvre of only thirteen films in fifty years with another discourse on spiritual and mystic values in a world, where money is everything and everywhere. AS/MT

THE COLOUR OF MONEY | BARBICAN LONDON EC2 | 10 – 20 SEPTEMBER 2015