Andre Simonoveisz looks at Polish Cinema from 1945 until the 1970 in the first part of our Kinoteka 2015 series curated by Martin Scorsese | MARTIN SCORSESE SELECTS | POLISH MASTERPIECES

During the Second World War years Poland was under German occupation and no Polish films were produced. The film industry’s output between 1945 and 1948 was a meagre four. The foundation of the Lodz Film School in 1948 can therefore be seen as the rebirth of Polish cinema. After the two film schools, one for actors, one for technical crew, were amalgamated in 1958, the standard of Polish films rose dramatically to a level never seen before. Another reason for this aesthetic quality and uniqueness was due to the relaxation of State censorship, after the death of Stalin in 1953.

For ten years, until the Prague Spring of 1968 frightened the cultural bureaucrats back into their burrows, nearly all important directors in Poland had some connection with Lodz Film school. Andrzej Wajda, whose ASHES AND DIAMONDS (1958) straddles the periods of Social Realism and Third Polish Cinema, which was one of ‘Moral Choices;. Apart from Wajda, (whose films dominate these movements), Andrzej Munk (1922-1961), who is represented with EROICA (1957), was one of the main directors to come out of the early years of the Lodz film school. Also prominent were Wojciech J. Has with THE HOUR GLASS SANATORIUM (1973, THE SRAGOSSA MANUSCRIPT, 1964 and Jerzy Kawalerowicz: MOTHER JOAN (1961), AUSTERIA (1982).

The rejection of Social Realism meant that this period of Polish feature films were mainly concerned with psychological and existential questions. Jerzy Skolimowski (1938), was the youngest of these directors with his sixties New Wave outing WALKOVER (1965) and Roman POLANSKI, with KNIFE IN THE WATER (1961) would soon leave Poland to work abroad. They could be seen as a link to the next stage of development, the Cinema of Moral Anxiety, which lasted from 1976 to 1981. This era is mainly represented by Krzysztof Kieslowski (1941 – 1996) with A SHORT FILM ABOUT KILLING (1987) and BLIND CHANCE (1981), and Krzysztof Zanussi (CAMOUFLAGE, 1976, THE CONSTANT FACTOR (1980) and ILLUMINTATION (1972). Also worth noting is Agnieszka Holland, part of the last movement of films between 1948 and 1982 , whose PROVINCIAL ACTORS (1978) is the only film by a woman director in this showcase of Polish masterpieces. AS

KRZYZACY KNIGHTS OF THE BLACK CROSS, (1960) was one of the most popular movies of its time in Poland. Based on the novel of the Polish author Henryk Sienkiewicz (Quo Vadis), written in 1900, when Poland did not exist as a state; the fervent nationalist tenor of book and film (it was the first Polish book published after WWII) was a major factor in the success of the film. A tragic romantic story, it is set around the battle of Grunwald in 1410 between the then Kingdom of Poland and the Teutonic order. Directed in 1960 by the veteran Aleksander Ford, it showed a small and divided Poland, the German army had occupied Poland since the Crusade of the 12th century, their, not very honest, motivation was to bring Christianity to Poland. In the summer of 1410 the combined forces of Poland and Lithuania defeated the Order and brought an end to German domination in Central Europe.

KRZYZACY KNIGHTS OF THE BLACK CROSS, (1960) was one of the most popular movies of its time in Poland. Based on the novel of the Polish author Henryk Sienkiewicz (Quo Vadis), written in 1900, when Poland did not exist as a state; the fervent nationalist tenor of book and film (it was the first Polish book published after WWII) was a major factor in the success of the film. A tragic romantic story, it is set around the battle of Grunwald in 1410 between the then Kingdom of Poland and the Teutonic order. Directed in 1960 by the veteran Aleksander Ford, it showed a small and divided Poland, the German army had occupied Poland since the Crusade of the 12th century, their, not very honest, motivation was to bring Christianity to Poland. In the summer of 1410 the combined forces of Poland and Lithuania defeated the Order and brought an end to German domination in Central Europe.

The eye-patch wearing Knight Jurand stops the Black Cross invaders from imprisoning merchants – as a revenge act, the order kills Jurand’s wife. His daughter Danusia (Grazyna Staniszewska) falls for the poor nobleman Zbyszko (Mieczyslaw Kalenik), who vows to avenge Danusia’s mother’s death. After their engagement, Siegfried de Lowe – who is an allie of the Germans – kidnaps Danusia. The new leader of the Teutonic Kinghts, Ulrich, declares war on Poland and Lithuania, which leads to the battle of Grunwald in 1410. Shortly before, Zbyszko frees Danusia, but she has lost her mind, and dies shortly after. Zbyszko, one of the heroes of the battle, finally marries his childhood girl friend Jagienka.

Ford had a long and unhappy relationship with the authorities in Poland. In 1947, after having set up “Film Polski”, he fell foul of the Soviet censorship. He fled to Prague, but returned, rather opportunistic, to make films in the approved manner of “socialist realism’, being praised by the authorities. At the end of the sixties, he again emigrated, this time to Germany, where he directed a film in 1975. After emigrating once again, this time to the USA, he committed suicide in Florida in 1980.

Andrzej Munk’s EROICA (1957) is a thesis on ‘heroism’ in two parts. Part one “Scherzo alla Polacca”, is set before the Warsaw uprising in August 1944. Dzidzius leaves the planning soldiers, and returns to his wife, deciding that he is not cut out to be hero. A Hungarian officer tells him that he and his men are ready to change sides, if the Russians can give them guarantees. Often drunk and full of self pity, Dzidzius tries to broker a pact between the two sides, but the deal falls apart. Left with nothing to show for his efforts Dzidzius returns to the uprising – just to please a friend. Dzidzius is anything but a hero, he is a man without many attributes, who is selfish but too afraid that others might find him out – he cares more for appearances, than his own integrity. Part two of EROICA, ”Ostinato lugubre”, is about a created myth based on false heroism: Lieutenant Zawistowski is hiding in the roof section of the barracks in a prison camp. In order to keep morale up, his fellow prisoners are told that he has successfully escaped while he is really being fed by two friends. But Zawistowski cannot endure the loneliness and kills himself. His friends remove his body secretly from the camp, so as to keep the myth –and the hope of the prisoners – alive. EROICA is very dark, and Munk was not only attacked for “formulism”, but also for “blackening the memory of Polish heroes”. But EROICA is deeply humanistic, showing that nobody is made to be a hero; circumstances dictate our fate much more than the best intentions.

Andrzej Munk’s EROICA (1957) is a thesis on ‘heroism’ in two parts. Part one “Scherzo alla Polacca”, is set before the Warsaw uprising in August 1944. Dzidzius leaves the planning soldiers, and returns to his wife, deciding that he is not cut out to be hero. A Hungarian officer tells him that he and his men are ready to change sides, if the Russians can give them guarantees. Often drunk and full of self pity, Dzidzius tries to broker a pact between the two sides, but the deal falls apart. Left with nothing to show for his efforts Dzidzius returns to the uprising – just to please a friend. Dzidzius is anything but a hero, he is a man without many attributes, who is selfish but too afraid that others might find him out – he cares more for appearances, than his own integrity. Part two of EROICA, ”Ostinato lugubre”, is about a created myth based on false heroism: Lieutenant Zawistowski is hiding in the roof section of the barracks in a prison camp. In order to keep morale up, his fellow prisoners are told that he has successfully escaped while he is really being fed by two friends. But Zawistowski cannot endure the loneliness and kills himself. His friends remove his body secretly from the camp, so as to keep the myth –and the hope of the prisoners – alive. EROICA is very dark, and Munk was not only attacked for “formulism”, but also for “blackening the memory of Polish heroes”. But EROICA is deeply humanistic, showing that nobody is made to be a hero; circumstances dictate our fate much more than the best intentions.

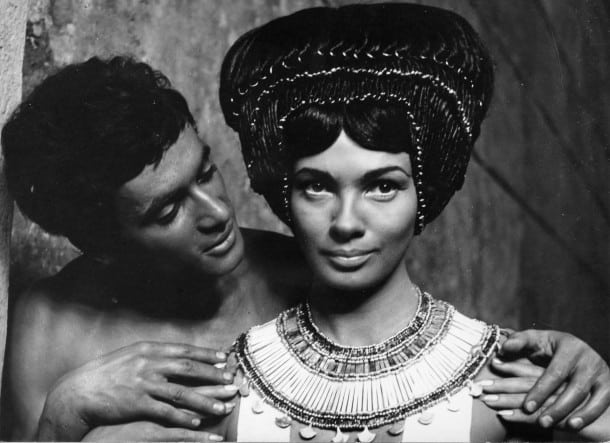

PHARAOH (FARAON) took director Jerzy Kawalerowicz three years to finish, on its premiere in 1966, it was the most expensive Polish film mad with a running time of 175 minutes, which seems, for once, apt, since this is not a spectacle in the DeMille style, but a political excurse, with many parallels to contemporary Poland – if one reads between the lines.

PHARAOH (FARAON) took director Jerzy Kawalerowicz three years to finish, on its premiere in 1966, it was the most expensive Polish film mad with a running time of 175 minutes, which seems, for once, apt, since this is not a spectacle in the DeMille style, but a political excurse, with many parallels to contemporary Poland – if one reads between the lines.

The main struggle is between Ramses XIII (Jerzy Zelnik), a modern ruler, who cares for the whole country – unlike his main opponent, the scheming High Priest Herhor, who wants to manipulate the Pharaoh into wars, he cannot win. Between the two men, Sarah, the Hebrew concubine of Ramses XIII, and mother of his son, is slowly written out of the picture, when Herhor’s oily assistant, tries successfully for the Assyrian princess to seduce Ramses. Simply read Gomolka – Poland’s prime minister of the 50s, who had been imprisoned by the Russians, before they freed him to placate the Polish comrades – for Ramses, and the evil priests for the Stalinist ideologists, and you get the picture.

Shot in Luxor, Cairo and Uzbekistan, PHARAOH has its spectacular moments, but the director never falls into the trap to overload the film with exotica or mass scenes. From the beginning, PHARAOH has a very measured pace, the intellectual and emotional confrontations at court are always the centre peace. Debate rather than battle dominates. Ramses is shown as a sometimes confused ruler, who oscillates between dictating his rights to be the supreme ruler, and his wish for compromise. In the end, he is easy prey for the manipulating priests, who are in tandem with foreign powers. PHARAOH is a reflection on power, and its limits.

POPIOL I DIAMNAT (ASHES AND DIAMONDS) directed by Andrzej Wajda in 1958 is undoubtedly a film noir. Not only has Wajda borrowed the angled shadows and the black and white aesthetics from the masters of the genre, but he also has given the film a hero, who is already as good as dead at the beginning of the film. Maciek Chelmicki (Zbigniew Cybulski) and his friend Andrzej are fighters for the Polish Home Army, who fought against the Germans for the Government in Exile in London. Now, on May 8th 1945, their new enemies are the communists. They get the order to kill the party secretary Szczuka. The men fail, and kill two civilians instead. After spending the night with the bar maid Krystyna, Maciek shoots the party secretary the next day, and escapes with Andrzej on a lorry. They meet Drewnowski, a communist functionary, who is working for Home Army, who warns the two. Maciek, who does not know that Drewnowski is on his side, runs away, is shot and dies on a rubbish dump. The greatest irony is, that Wajda’s interpretation of the film differs diametrical from the production studio ‘Kadr’ and indeed the whole Stalinist state apparatus, which obviously saw the two assassins as counter-revolutionaries, coming to an deserved end. For Wajda, and some of the crew and cast, the opposite was true. But even with a pro-communist interpretation, ASHES AND DIAMONDS is a deeply nihilistic film: even though the war is won, the destruction is total, and the future looms grey and unwelcoming. The film was shot in a small town, were nearly everybody knew each other. Nobody trusts their neighbours: be it for collaboration with the Germans, or the competition for a place in the new order – this is a fearful town. The firework, which celebrates the end of the war, and masks the shots fired by Maciek, is anything but a signal for peace. Dark and foreboding, ASHES AND DIAMONDS is not so much the final chapter of WWII, but the first skirmish of an occupation.

POPIOL I DIAMNAT (ASHES AND DIAMONDS) directed by Andrzej Wajda in 1958 is undoubtedly a film noir. Not only has Wajda borrowed the angled shadows and the black and white aesthetics from the masters of the genre, but he also has given the film a hero, who is already as good as dead at the beginning of the film. Maciek Chelmicki (Zbigniew Cybulski) and his friend Andrzej are fighters for the Polish Home Army, who fought against the Germans for the Government in Exile in London. Now, on May 8th 1945, their new enemies are the communists. They get the order to kill the party secretary Szczuka. The men fail, and kill two civilians instead. After spending the night with the bar maid Krystyna, Maciek shoots the party secretary the next day, and escapes with Andrzej on a lorry. They meet Drewnowski, a communist functionary, who is working for Home Army, who warns the two. Maciek, who does not know that Drewnowski is on his side, runs away, is shot and dies on a rubbish dump. The greatest irony is, that Wajda’s interpretation of the film differs diametrical from the production studio ‘Kadr’ and indeed the whole Stalinist state apparatus, which obviously saw the two assassins as counter-revolutionaries, coming to an deserved end. For Wajda, and some of the crew and cast, the opposite was true. But even with a pro-communist interpretation, ASHES AND DIAMONDS is a deeply nihilistic film: even though the war is won, the destruction is total, and the future looms grey and unwelcoming. The film was shot in a small town, were nearly everybody knew each other. Nobody trusts their neighbours: be it for collaboration with the Germans, or the competition for a place in the new order – this is a fearful town. The firework, which celebrates the end of the war, and masks the shots fired by Maciek, is anything but a signal for peace. Dark and foreboding, ASHES AND DIAMONDS is not so much the final chapter of WWII, but the first skirmish of an occupation.

NIEWINNI CZARODZIE (INNOCENT SORCERERS, 1960) is set in contemporary Warsaw. Bazyl (Tadeusz Lomnicki) is a young doctor and plays in a jazz band. He is a dreamer, not really unhappy, but indolent. His fake blond hair is one of he reasons for his popularity with women, but he is unable to commit. At work, where he looks after the boxers of a state run club, he is equally bored. Only music seems to keep him alive, but afterwards he hangs around in the pubs, waiting for something to happen. Bazyl’s friend Edmund (Zbigniew Cybulski) hands out with him during the long nights, hoping in vain, to pick up one of the women who lusts after Bazyl. One evening, the two men set a trap for Edmund to get off with one of the girls, but the young Pelagia (Krystyna Stypolkowska) does not fall for it, and Bazyl – originally against his will – spends the night with her. He leaves Pelagia the next morning, only to find her in his flat on his return: Bazlyl doesn’t want to acknowledge that he has fallen in love with her, neither does he want to show her any signs of affection. When she wants to leave, Bazyl lets her go against his better judgement. Roman Polanski has a vignette playing bass. Although Wajda directed the film, it very much belongs to scripter, Jerzy Skolimowski’s; Bazyl being a prototype of Skolimowski’s hero in Walkover. INNOCENT SORCERERS is full of ironies and alienation. Bazyl and Edmund are running away from a society with which they have nothing in common, but, equally, they are not committed to anything – they are directionless, wasting their time. Hardly surprising, therefore, that Bazyl is no match for Pelagia, who looks through him from the start. Bazyl started out trying to manipulate Pelagia into Edmunds arms, but ends up being her prey. The camera shows melancholic images of a rather nondescript environment, the pubs are are as faceless as Bazyl’s studio flat. The characters seem to live in a void, only music keeping them alive.

NIEWINNI CZARODZIE (INNOCENT SORCERERS, 1960) is set in contemporary Warsaw. Bazyl (Tadeusz Lomnicki) is a young doctor and plays in a jazz band. He is a dreamer, not really unhappy, but indolent. His fake blond hair is one of he reasons for his popularity with women, but he is unable to commit. At work, where he looks after the boxers of a state run club, he is equally bored. Only music seems to keep him alive, but afterwards he hangs around in the pubs, waiting for something to happen. Bazyl’s friend Edmund (Zbigniew Cybulski) hands out with him during the long nights, hoping in vain, to pick up one of the women who lusts after Bazyl. One evening, the two men set a trap for Edmund to get off with one of the girls, but the young Pelagia (Krystyna Stypolkowska) does not fall for it, and Bazyl – originally against his will – spends the night with her. He leaves Pelagia the next morning, only to find her in his flat on his return: Bazlyl doesn’t want to acknowledge that he has fallen in love with her, neither does he want to show her any signs of affection. When she wants to leave, Bazyl lets her go against his better judgement. Roman Polanski has a vignette playing bass. Although Wajda directed the film, it very much belongs to scripter, Jerzy Skolimowski’s; Bazyl being a prototype of Skolimowski’s hero in Walkover. INNOCENT SORCERERS is full of ironies and alienation. Bazyl and Edmund are running away from a society with which they have nothing in common, but, equally, they are not committed to anything – they are directionless, wasting their time. Hardly surprising, therefore, that Bazyl is no match for Pelagia, who looks through him from the start. Bazyl started out trying to manipulate Pelagia into Edmunds arms, but ends up being her prey. The camera shows melancholic images of a rather nondescript environment, the pubs are are as faceless as Bazyl’s studio flat. The characters seem to live in a void, only music keeping them alive.

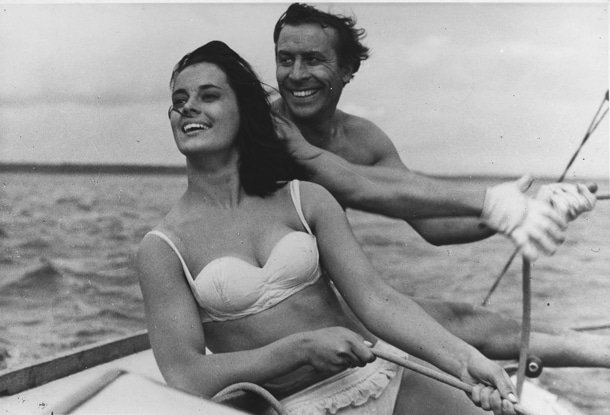

Roman Polanski’s debut feature NOZ W WODZIE (KNIFE IN THE WATER) 1962 | is a parable. Andrzej (Leon Niemczyk) plays a successful functionary and heroic ex-partisan. Driving to to his coast for a sailing break, he and his wife, Krystyna ( Jolanta Umecka) pick up a a rough hitch-hiker (Zygmunt Malanowicz). To impress his wife, Andrzej invites the young man to join them on the sailing trip, hoping very much to get the upper hand and show his wife that there there is still something of a hero in him. But the young man turns the tables, and finally Krystyna sleeps with him. But her verdict leaves a bitter taste for the “victor”: “You will end up exactly like him”. On the way home, the trio is mostly in awkward silence. NOZ W WODZIE is a film about the need for male confrontation in private life, and man’s opportunism in the public domain. Andrzej lives in his heroic past, but the present is anything but: he is a public servant, despite his car and sailing boot, the trappings of success in a political system which relies on obedience. His wife looks at him as a “has-been”, and the young man as his younger double. Polanski’s irony becomes apparent in the little story Andrzej tells, which is a parallel to the main narrative: A sailor wants to show off, he shatters a glass bottle, and jumps onto the shards. He bleeds heavily, having forgotten that he used to do this party trick a long time ago, when he was working in the ships engine room, where the hot ash had toughened the soles of his feet. Time had moved on.

Roman Polanski’s debut feature NOZ W WODZIE (KNIFE IN THE WATER) 1962 | is a parable. Andrzej (Leon Niemczyk) plays a successful functionary and heroic ex-partisan. Driving to to his coast for a sailing break, he and his wife, Krystyna ( Jolanta Umecka) pick up a a rough hitch-hiker (Zygmunt Malanowicz). To impress his wife, Andrzej invites the young man to join them on the sailing trip, hoping very much to get the upper hand and show his wife that there there is still something of a hero in him. But the young man turns the tables, and finally Krystyna sleeps with him. But her verdict leaves a bitter taste for the “victor”: “You will end up exactly like him”. On the way home, the trio is mostly in awkward silence. NOZ W WODZIE is a film about the need for male confrontation in private life, and man’s opportunism in the public domain. Andrzej lives in his heroic past, but the present is anything but: he is a public servant, despite his car and sailing boot, the trappings of success in a political system which relies on obedience. His wife looks at him as a “has-been”, and the young man as his younger double. Polanski’s irony becomes apparent in the little story Andrzej tells, which is a parallel to the main narrative: A sailor wants to show off, he shatters a glass bottle, and jumps onto the shards. He bleeds heavily, having forgotten that he used to do this party trick a long time ago, when he was working in the ships engine room, where the hot ash had toughened the soles of his feet. Time had moved on.

REKOPIS ZNALEZIONY W SARAGOSSIE (THE SARAGOSSA MANUSCRIPT (1965) is one of the most mythical films of Polish cinema. Directed by Wojciech Haas in 1964, SARAGOSSA is based on a novel written between 1813 and 1815 by Jan Potocki. SARAGOSSA is an adventure, told in flashbacks, constructed like a “Russian Doll”: each story opens another surprising new story. During a battle for Saragossa, a Spanish officer discovers an old manuscript, which tells the stories of his ancestor, a certain Van Worden. In a remote inn Van Worden meets two exotic sisters, Emina and Zibelda, who ask him to become the fathers of their children. Van Worden enjoys this adventure, but passes out after getting drunk. He wakes up next morning under the gallows. Here, the real adventure starts: Van Worden gets involved in the gruesome Spanish Inquisition, and flees to a castle of a Cabalist. In the end, the audience learns that all these escapades were just a test of Van Worden’s bravery. He carries on his journey to the King’s Castle, stopping at another inn, where two ladies are introduced to him: Emina and Zibelda… Van Worden flees in panic. SARAGOSSA is a romantic comedy, with stylish aesthetics and a feeling for subtle irony.

REKOPIS ZNALEZIONY W SARAGOSSIE (THE SARAGOSSA MANUSCRIPT (1965) is one of the most mythical films of Polish cinema. Directed by Wojciech Haas in 1964, SARAGOSSA is based on a novel written between 1813 and 1815 by Jan Potocki. SARAGOSSA is an adventure, told in flashbacks, constructed like a “Russian Doll”: each story opens another surprising new story. During a battle for Saragossa, a Spanish officer discovers an old manuscript, which tells the stories of his ancestor, a certain Van Worden. In a remote inn Van Worden meets two exotic sisters, Emina and Zibelda, who ask him to become the fathers of their children. Van Worden enjoys this adventure, but passes out after getting drunk. He wakes up next morning under the gallows. Here, the real adventure starts: Van Worden gets involved in the gruesome Spanish Inquisition, and flees to a castle of a Cabalist. In the end, the audience learns that all these escapades were just a test of Van Worden’s bravery. He carries on his journey to the King’s Castle, stopping at another inn, where two ladies are introduced to him: Emina and Zibelda… Van Worden flees in panic. SARAGOSSA is a romantic comedy, with stylish aesthetics and a feeling for subtle irony.

MATKA JOANNA OD ANILOW (MOTHER JOAN OF THE ANGELS (1961) is based on real events in Loudon, France around 1730. Jerzy Kawalerowicz has transferred the narrative to Poland, but kept close to events. MOTHER JOAN begins after the first outbreak of devil worship in the Ursuline cloister. Renewed outbreaks of devil worship and sexual transgressions bring Father Suryn (Mieczyslaw Voit) on the plan, to finish the finish the heresy once and for all. But Suryn falls in love with the Mother superior Joanna (Lucyna Winnicka), whilst Sister Margarete (Anna Ciepielewska) even spends a night with a wealthy landowner in the very inn, Suryn is staying. The father has to fight to repress his carnal lust for Joanna; in one of the great scenes, the two are seen in flagellation, both of them half-naked, but far apart, in the attic. Joan cannot overcome her guilt for not achieving Sainthood status, and also wants to be punished for her forbidden lust. Suryn wants to scarify himself, mainly to save Joanna. The dark gloom of the main locations, the inn and the cloister, is often shattered by a glaring white light; the white of the nuns’ robes and the horses’ coat, the latter galloping around a barren landscape, are set like counter points in a medieval painting. Subtle panning shots allow a change of levels from the subjective to the objective. In the end, Joanna and Father Suryn are both the victims of totalitarian demands by the church, which forbids love and drives Suryn into murder. MOTHER JOAN is a rejection of any dogma, and for once, it was the Catholic Church (not the state censors), who wanted a Polish movie banned from being shown in Cannes, where MOTHER JOAN won the “Special Price” of the Jury in 1961. Its impressive, but modest aesthetics, very much in line with Bresson’s formal ascetics, give the film the feeling of an eternal parable. AS

MATKA JOANNA OD ANILOW (MOTHER JOAN OF THE ANGELS (1961) is based on real events in Loudon, France around 1730. Jerzy Kawalerowicz has transferred the narrative to Poland, but kept close to events. MOTHER JOAN begins after the first outbreak of devil worship in the Ursuline cloister. Renewed outbreaks of devil worship and sexual transgressions bring Father Suryn (Mieczyslaw Voit) on the plan, to finish the finish the heresy once and for all. But Suryn falls in love with the Mother superior Joanna (Lucyna Winnicka), whilst Sister Margarete (Anna Ciepielewska) even spends a night with a wealthy landowner in the very inn, Suryn is staying. The father has to fight to repress his carnal lust for Joanna; in one of the great scenes, the two are seen in flagellation, both of them half-naked, but far apart, in the attic. Joan cannot overcome her guilt for not achieving Sainthood status, and also wants to be punished for her forbidden lust. Suryn wants to scarify himself, mainly to save Joanna. The dark gloom of the main locations, the inn and the cloister, is often shattered by a glaring white light; the white of the nuns’ robes and the horses’ coat, the latter galloping around a barren landscape, are set like counter points in a medieval painting. Subtle panning shots allow a change of levels from the subjective to the objective. In the end, Joanna and Father Suryn are both the victims of totalitarian demands by the church, which forbids love and drives Suryn into murder. MOTHER JOAN is a rejection of any dogma, and for once, it was the Catholic Church (not the state censors), who wanted a Polish movie banned from being shown in Cannes, where MOTHER JOAN won the “Special Price” of the Jury in 1961. Its impressive, but modest aesthetics, very much in line with Bresson’s formal ascetics, give the film the feeling of an eternal parable. AS

KINOTEKA | RUNS FROM 8 APRIL UNTIL 29 MAY IN LONDON AND NATIONWIDE