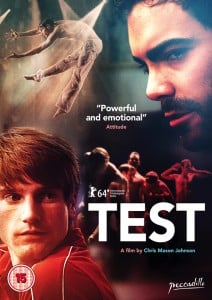

Alex Barrett spoke to Chris Mason Johnson during his recent visit to London. His latest film TEST is now out on DVD.

The first thing that strikes me about Chris Mason Johnson is how friendly he is. Conversation strikes up as soon as we meet, and before I’ve even finished turning on my recorders, we’ve already neatly segued into talking about filmmaking, discussing the pros and cons of updating editing software (as well as being a writer/director, Mason Johnson also serves as editor on his films). It comes up that I’m a filmmaker too, stuck in that awkward place between first and second feature. He comments that ‘the time it takes to get another feature up can be…challenging’, saying it in such a way that I feel there’s a story to be told. It’s not where I’d intended to start, but, I decide to ask him about the journey he’s been on since the release of his first feature The New Twenty (2008). He lets out a long, frustrated exhale, and we both laugh – it’s a feeling all filmmakers know only too well. He picks up the story:

CMJ: After The New Twenty, I launched into a new project – an independent comedy, also with a gay theme, but more mainstream. It had a bigger budget, $3-5 million, and I got caught in that waiting around game in L.A. It was a very frustrating couple of years. It was optioned, it won a prize, it was going to get made, and then it wasn’t and… long story short, I had the feeling as an artist that I’d given all my power away. I was powerless to do anything. I was just waiting for other people. So I flipped 180 degrees and I said ‘I know how to make a film. I’m going to do that now’. So I started writing Test as something very small and personal, something that I knew I could make for the couple of hundred thousand that I felt I could raise. And I did that. It was a great lesson and a great experience, because I remembered that I could make things. I think filmmakers trying to fit into a large, complicated industry, it’s easy to forget that. As a writer or a painter you don’t forget, because you wake up and there’s a canvas or there’s a blank page. But as a filmmaker, it’s very easy to forget that – and I think, as an artist, it’s important not to forget that.

CMJ: After The New Twenty, I launched into a new project – an independent comedy, also with a gay theme, but more mainstream. It had a bigger budget, $3-5 million, and I got caught in that waiting around game in L.A. It was a very frustrating couple of years. It was optioned, it won a prize, it was going to get made, and then it wasn’t and… long story short, I had the feeling as an artist that I’d given all my power away. I was powerless to do anything. I was just waiting for other people. So I flipped 180 degrees and I said ‘I know how to make a film. I’m going to do that now’. So I started writing Test as something very small and personal, something that I knew I could make for the couple of hundred thousand that I felt I could raise. And I did that. It was a great lesson and a great experience, because I remembered that I could make things. I think filmmakers trying to fit into a large, complicated industry, it’s easy to forget that. As a writer or a painter you don’t forget, because you wake up and there’s a canvas or there’s a blank page. But as a filmmaker, it’s very easy to forget that – and I think, as an artist, it’s important not to forget that.

AB: Test is set in 1985, against the backdrop of the first effective HIV-tests. Can you tell me what it was about this time period that interested you? What drew you to it.

CMJ: Well, I was there. I was a very young dancer, a professional at 16-17. I lived through it. So I was drawing on personal history. What interested me, aside from the fact that it was me, was that the AIDS movies that we have seen up to now have mostly been deathbed stories – stories of people getting sick and dying. That’s natural. When you’re dealing with this subject, it’s natural that narratively that’s where it would go. But I wanted to do something different, something that was more hopeful – something lighter that showed somebody coming through and surviving. At the end of The Celluloid Closet, Vito Russo has a necrology of all the different ways gay characters die, and I didn’t want to add to that necrology. I wanted someone to live and be happy. And I think the time was right to tell that story, because the other stories really did need to be told first: they were more important politically and emotionally. But I think enough time has now passed that this other story can be told.

AB: You’ve mentioned that you were there, that you lived through this – that raises the question of how autobiographical the film is.

CMJ: I think anyone, any filmmaker or novelist who draws on their own life for their material, will be very quick to tell you ‘it’s not me’. And I would say the same thing. Yes, I’m drawing on my experience, but also it’s not me. My experience was different in lots of key ways. But I was in a [dance] company. I was in New York, not San Francisco, but I had a lot of real stuff to draw from.

AB: Aside from your own background, was there something else that made you want to explore the dance world on film?

CMJ: A couple of things. Dance world movies tend to focus on women – from The Red Shoes to The Turning Point to Black Swan, it’s usually a very classical ballerina. And then there’s Billy Elliot, but I don’t think it’s any accident that he’s pre-sexual. I think it’s very difficult to deal seriously with a sexualised – as in adult – male dancer. Because, the ‘men in tights’…it’s actually a subtitle of a Mel Brooks film, Robin Hood: Men in Tights. It’s just automatically a joke. So to treat a character seriously as someone who’s gay and who’s a dancer, who might even wear tights, and to treat that character as a serious person, that was something I wanted to do. And then also…As a former dance who knows the dance world well, and who knows choreography well, dance on film is frankly, in my opinion, cheesy stuff. You know, there’s some great dance on film like DV8, a British group who do short dance films – but they’re not narrative features. So I wanted to put some good dance and choreography on film. So it was those two aspects.

AB: I’ll come back to the choreography in a minute, but something else that struck me about the dance world of Test was the camaraderie. Often when I see films about dance companies, they tend to be about competition, rivalry or obsession, whereas I felt like the characters in Test had a real bond between them. Was that also a deliberate decision on your part – an attempt to do something different? Or was that just what you experienced when you were there?

CMJ: Well, I guess both. I like the way you focused that question – that is true. I think as a screenwriter I understand that anytime you deal with a given subject, you’re led into certain narrative tropes, and the dance world, as you say, tends to lead towards competition and obsession. The other dance world trope is, of course, ‘the understudy goes on’ – and I did engage with that cliché intentionally. I wanted to disarm it, so to speak, by taking what would be the normal climax of the movie – where the understudy goes on at the end, if it was Black Swan or 42nd Street or Moulin Rouge, or anything else – and put it in the middle, as if to say ‘this isn’t the focus’. He’s a professional, this is what he does: he’s an understudy that goes on. He wakes up and it’s another day, it wasn’t even a big deal [that he went on]. So I did want to disarm that cliché.

In terms of the camaraderie – absolutely. I mean, every experience I had in every dance company was like that. It’s like any band of people doing a difficult job, whether it’s the army or hospital work or theatre or dance… you bond in that work. There’s a tremendous amount of camaraderie in the dance world, and it’s true that’s not really represented very often in film.

AB: To go back to the choreography… The dance sequences were predominantly choreographed by Sidra Bell. Could you tell me about how she got involved, and how you worked together on the film?

CMJ: She’s a very talented New York based choreographer, and her work had actually been influenced by William Forsythe’s work in Frankfurt, which was a company – the Frankfurt Ballet – that I was in way back when. So I liked her aesthetic. I recognised it. And then, we did it very quickly, in two weeks. I was with her as a kind of editor, making suggestions in the studio, that kind of thing.

AB: And at what stage did she get involved? Is this something that was happening during the shoot, or already at script stage?

CMJ: I knew that it was a huge part of the movie because, on our budget, I knew that all the production value and spectacle I was going to have was from the stage. So it was hugely important to get that choreography right. So I brought her in early on. We spent two weeks choreographing it and setting it, immediately prior to the shooting schedule. It was a four week shooting schedule, so the two weeks before that were the choreography.

AB: Scott Marlowe, who plays Frankie, has a background in dance rather than in acting. What sort of challenges did that present you with?

CMJ: Well, that was the thing. You know, Natalie Portman did an amazing job in Black Swan, but when it came to the really technical stuff, like the fouetté, she did have a double. This kind of dance is not something you can fake. It’s what opera singing is to pop music, you know? You can sing a song on camera if you can carry a tune, but you couldn’t sing opera. And this dance is like that – you just can’t do it unless you’re in that field. So I interviewed dancers who had an instinct for acting and seemed natural. Scott seemed natural, and then I worked with him for six months prior to the shoot, work-shopping scenes and teaching him acting technique, which he really loved. He’s gone on to do more. So he’s a real collaborator, a real partner on the film.

AB: Do you think your own background as a dancer has affected the way your approach cinema or the way you make films?

CMJ: I think so. I mean, there’s a long history of dancers and choreographers making films – from Busby Berkeley in the 30s, through experimental work like Maya Deren, through Herbert Ross Rob Marshall and Bob Fosse… Dancers and choreographers have eyes trained for movement, and cinema is about movement. The difference is that you have movement within the frame, and you have movement between the frames with the cuts – you’re just playing with different ideas of movement. The camera becomes like another moving body. So I think it’s very easy for choreographers and dancers to grasp the kinetic aspects of filmmaking. I think it’s a natural transition.

AB: Saying that, though – and forgive me if you don’t agree – Test doesn’t feel like a film with a lot of camera movement, apart from that amazing moment when Frankie comes up the stairs and walks into the empty apartment.

CMJ: There’s actually a lot of dolly and handheld. It stays close to him, and it’s a very intimate feel. But it doesn’t call attention to itself, apart from that sequence which you mention – which is maybe why you remember it, as a technical moment with lots of dolly tracks. But throughout the film there’s a lot of handheld that stays close to him and just creates a feeling of intimacy.

AB: So when you approach that, are you choreographing it like you’re choreographing the actors?

CMJ: Absolutely. We blocked it out, choreographed it, and then my DP – who’s a super talented guy named Daniel Marks, who I call the human dolly – he becomes the other body moving through the space.

AB: Right from the start of the film, there’s a great onscreen chemistry between Scott Marlowe and Matthew Risch. It feels like the film places its emphasis elsewhere, but to me it plays as almost like a love story between the two of them. To what extent did you see it in those terms?

CMJ: I do see it in those terms now. It’s not a love story conventionally, because the connection happens very late, but it does have that feeling, yeah. I didn’t set out for it to be that, but it became that in the writing. And then, when I cast it, I knew I had to have chemistry between these guys, so I looked for it and I found it. I have worked with actors who don’t have chemistry before, so I… there’s a reason why there’s something called ‘the chemistry read’ in Hollywood. It’s hugely important because your work is done for you if there’s a spark there. And they definitely had a spark there.

AB: Going back to the era that the film is set in…There’s a sense in the film, for me, that the HIV-test signals the end of an era, and I felt like the film really captures the complexity of that moment: on the one hand, the growing awareness of AIDS is dampening the sense of sexual freedom, but on the other, the test is putting an end to the paranoia and uncertainty that the characters feel. Could you comment on this?

CMJ: The first part I agree with: it put an end to a certain kind of ‘culture of promiscuity’ – I’m not trying to judge it by using that word, but there was definitely a shift there. But the second part…I don’t think that’s exactly right, because for several years there was quite a bit of paranoia about what would be done with the test by the government. There was real fear, real talk, and ACT UP in part was founded to make sure that the government couldn’t keep those records. That went on for several years. Also, the test was a death sentence: there was no treatment, there was nothing anyone could do, so many people opted not to take it, because what was the point? It was to protect other people. So no, I think from ’85 through to the mid-’90s, when the Protease Inhibitors drug treatment came out, it was still a very dark and very uncertain period. In the context of the movie, the tiny era of panic, freak out and total ignorance – can you get it from mosquitos, can you get it from sweat, there’s no test – that sort of micro-era ended, maybe. But it’s a stretch to call it an era, because 85-95 was really a continuation of the horror.

AB: There’s a sense though, in the film – and maybe this is just something that I’m reading into it – of decay: the wooden bowl gets cracked and is replaced by plastic, which almost seems like a metaphor for condoms…

CMJ: [laughs] That’s good, I like that.

AB: …But all these things – the bowl breaks, the mice are coming in, the phone is tangled, the Walkman breaks down – all these things feel like a sign that things are ending, like doom is approaching.

CMJ: That’s an interesting reading of it. I definitely wanted a sense of morbidity, because disease is about morbidity, doom, fear and the decay of the body. And that’s why the choreography calls on images from Egon Schiele, an artist from Vienna from around the turn of the [twentieth] century… these images of morbidity and twistedness and decay. I wanted sexuality and eroticism to co-exist with that kind of morbidity, because that’s what you’re dealing with in that era. And most movies that deal with that subject sanitise the sex out, because it’s difficult for us to think about disease and sex at the same time – and that’s exactly what I wanted to do: to have this character be sexualised and eroticised, because he’s twenty and he wants to have sex. I didn’t want to vet that out of the story.

AB: I think we have to finish now, but just quickly: what’s next for you?

CMJ: I’m working on two things. One is a TV project which I’m developing, set in the 1970s, and the other is an independent film which I hope to shoot this summer in Berlin.

AB: And do you think you’ll go back to your big budget project, or is that finished with?

CMJ: I may, but it was a comedy about gay marriage – so I’d have to look at it again, because things have changed so quickly. I’d have to see whether I could make it as a period piece [laughs] or really update it.

TEST SCREENED AT THE BFI FLARE FESTIVAL AND IS NOW AVAILABLE ON DVD THROUGH PECCADILLO PICTURES