Dir. Maurce Pialat | Cast: Jacques Dutronc, Alexandra London,Gerard Sety, Bernhard Le Coq, Corinne Bourdon, Elizabeth Zylberstein. | France 1991, 158 min. Drama

French director Maurice Pialat (1925-2003) was a maverick: a late starter in film-making – he directed his first feature L’Enfance Nue (Naked childhood – in 1968 at the age of 44. An antagonistic person, he thrived on controversy, on and off the set. His relationship with the French film critics was poisonous: when he received the Palme D’Or in 1987 for Sous le soleil de Satan (Under the sun of Satan) he was roundly booed and retaliated by sticking out his tongue.

Sharing his lack of aesthetic compromise with Bresson (it’s no accident that Under the sun of Satan is based on a novel by Georges Bernanos, whose Mouchette and Diary of a Country Priest were filmed by Bresson). And Pialat was a painter – albeit with little success.

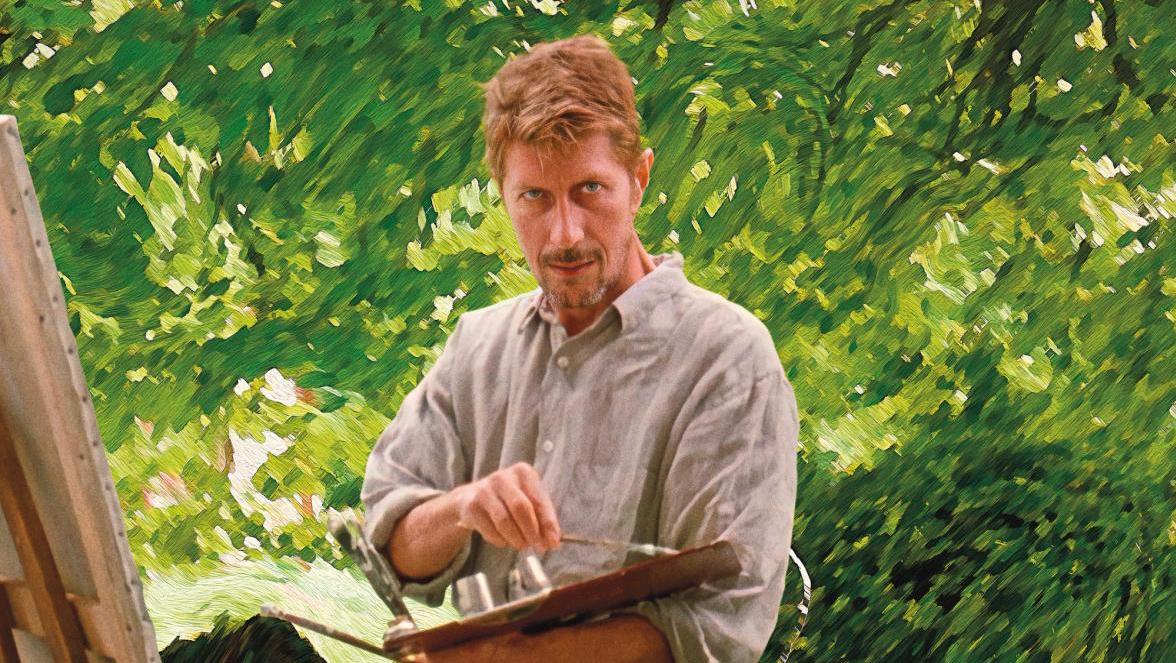

Dialogue-driven and aesthetically rather underwhelming, Van Gogh is well-crafted with a strong central performance from Jacques Dutronc who portrays the last three months of the artist’s life.

In May 1890 Vincent van Gogh arrives at the station of Auvers-sur-Oise, a little village 40 miles away from Paris, where is met by his friend Dr Gachet (Gerard Sety), an amateur collector of works by Cezanne, Renoir and other contemporary French painters. Van Gogh has just left the hospital in Saint Remy, after treatment for physical and mental illness. Even though Gachet wants to look after Van Gogh and admires his works he is wary of him; with good reason as it turns out. Van Gogh stays in a cheap inn, but sees Gachet regularly, meeting and painting his teenage daughter Marguerite (Alexandra London), with whom he forms a romantic bond. Brother Theo, an art dealer, also visits with wife Jo (Corinne Bourdon) at the Gachet place, where they have fun in the garden. Van Gogh works tirelessly, only interrupting his work when friends from Paris arrive, one of them is the Cathy (Elizabeth Zylberstein), who is supposed to be the love of his life. After a night out in Paris with Theo and Marguerite, Van Gogh sinks again into a deep depression and meets a tragic end.

Pialat mistrusted all forms of psychological interpretation. His long shots show what is happening, nothing else. He demystifies Van Gogh and argues, that if the painter had really been that ill, he could not have created so many masterpieces in the last two month of his life. In common with Eustache and Cassavetes, Pialat welcomed confrontation on many levels: On set, he drove the actors mad and even came to blows with many of them.

Pialat resolves many scenes with conflict, particularly those between couples (here Van Gogh/Marguerite and Theo/Jo are arguing constantly and violently. Like all Pialat’s films, Van Gogh is rigorously structured, nothing is left to interpretation. Unsentimental it may be, but the director is not interested in romantisicing the artist: his Van Gogh is a lonely, cantankerous man, unable to express himself in words, only knowing how to confront. Whilst he is not a misogynist, his relationships with women are mainly exploitative, at home in chaos and catastrophe – not unlike the director, whose films all have an underlying autobiographical tone. AS

VAN GOGH IS OUT ON DVD/BLU and a selection of his films are now on MUBI | COURTESY OF MASTERS OF CINEMA.